Substance of the Address of the Rev. Lord Arthur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Template:Ælfgifu Theories Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Template:Ælfgifu Theories from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

2/6/2016 Template:Ælfgifu theories Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Template:Ælfgifu theories From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Family tree, showing two theories relating Aelgifu to Eadwig, King of England Æthelred Æthelwulf Mucel King of Osburh Ealdorman Eadburh Wessex of the Gaini ?–839858 fl. 867895 Alfred Æthelred I the Great Æthelbald Burgred Æthelberht Æthelwulf Æthelstan King of King of the King of King of Æthelswith King of Ealhswith Ealdorman King of Kent Wessex Anglo Wessex Mercia d. 888 Wessex d. 902 of the Gaini ?–839855 c.848–865 Saxons ?–856860 ?–852874 ?–860865 d. 901 871 849–871 899 Edward the Elder Æthelfrith King of the (2)Ælfflæd Ealdorman Æthelhelm Æthelwold (1)Ecgwynn (3)Eadgifu Æthelgyth Anglo fl. 900s of S. Mercia fl. 880s d. 901 fl. 890s x903–966x fl. 903 Saxons 910s fl. 883 c.875–899 904/915 924 unknown Æthelstan Æthelstan Edmund I Eadric Eadred Ælfstan HalfKing Æthelwald King of King of Ealdorman King of Ealdorman Ealdorman Ealdorman unknown Æthelgifu the English the English of Wessex the English of Mercia of East of Kent c.894–924 921–939 fl. 942 923946955 fl. 930934 Anglia fl. 940946 939 946 949 fl. 932956 Eadwig Edgar I Æthelwald Æthelwine AllFair the Peaceful Æthelweard Ælfgifu Ealdorman Ealdorman King of King of historian ? Ælfweard Ælfwaru fl. 956x957 of East of East England England d. c.998 971 Anglia Anglia c.940955 c.943–959 d. 962 d. 992 959 975 Two theories for the relationship of Ælfgifu and Eadwig King of England, whose marriage was annulled in 958 on grounds of consanguinuity. -

WSC Planning Decisions 43/19

PLANNING AND REGULATORY SERVICES DECISIONS WEEK ENDING 25/10/2019 PLEASE NOTE THE DECISIONS LIST RUN FROM MONDAY TO FRIDAY EACH WEEK DC/15/2298/FUL Planning Application - (i) Extension and Village Hall DECISION: alterations to Hopton Village Hall (ii) Thelnetham Road Approve Application Doctor's surgery and associated car Hopton DECISION TYPE: parking and the modification of the existing Suffolk Committee vehicular access onto Thelnetham Road IP22 2QY ISSUED DATED: (iii) residential development of 37 24 Oct 2019 dwellings (including 11 affordable housing WARD: Barningham units) and associated public open space PARISH: Hopton Cum including a new village green, Knettishall landscaping,ancillary works and creation of new vehicular access onto Bury Road APPLICANT: Pigeon Investment Management AGENT: Evolution Town Planning LLP - Mr David Barker DC/18/0628/HYB Hybrid Planning Application - 1. Full Former White House Stud, DECISION: Planning Application - (i) Horse racing White Lodge Stables Refuse Application industry facility (including workers Warren Road DECISION TYPE: dwelling) and (ii) new access (following Herringswell Delegated demolition of existing buildings to the CB8 7QP ISSUED DATED: south of the site) 2. Outline Planning 22 Oct 2019 Application (Means of Access to be WARD: Iceni considered) (i) up to 100no. dwellings and PARISH: Herringswell (ii) new access (following demolition of existing buildings to the north of the site and the existing dwelling known as White Lodge Bungalow). APPLICANT: Hill Residential Ltd AGENT: Mrs Meghan Bonner - KWA Architects (Cambridge) Ltd Planning and Regulatory Services, West Suffolk Council, West Suffolk House, Western Way, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, IP33 3YU DC/19/0235/FUL Planning Application - 2no. -

WSC Planning Applications 14/19

LIST 14 5 April 2019 Applications Registered between 1st and 5th April 2019 PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED The following applications for Planning Permission, Listed Building, Conservation Area and Advertisement Consent and relating to Tree Preservation Orders and Trees in Conservation Areas have been made to this Council. A copy of the applications and plans accompanying them may be inspected on our website www.westsuffolk.gov.uk. Representations should be made in writing, quoting the application number and emailed to [email protected] to arrive not later than 21 days from the date of this list. Note: Representations on Brownfield Permission in Principle applications and/or associated Technical Details Consent applications must arrive not later than 14 days from the date of this list. Application No. Proposal Location DC/18/1567/FUL Planning Application - 2no dwellings AWA Site VALID DATE: Church Meadow 22.03.2019 APPLICANT: Mr David Crossley Barton Mills IP28 6AR EXPIRY DATE: 17.05.2019 CASE OFFICER: Kerri Cooper GRID REF: WARD: Manor 571626 274035 PARISH: Barton Mills DC/19/0502/HH Householder Planning Application - Two 10 St Peters Place VALID DATE: storey rear extenstion (following demolition Brandon 03.04.2019 of existing rear single storey extension) IP27 0JH EXPIRY DATE: APPLICANT: Mr & Mrs G J Parkinson 29.05.2019 GRID REF: AGENT: Mr Paul Grisbrook - P Grisbrook 577626 285941 WARD: Brandon West Building Design Services PARISH: Brandon CASE OFFICER: Olivia Luckhurst DC/19/0317/FUL Planning Application - 1no. dwelling -

International Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol

International Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 7, No. 3, September 2020 doi:10.30845/ijll.v7n3p2 Skaldic Panegyric and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Poem on the Redemption of the Five Boroughs Leading Researcher Inna Matyushina Russian State University for the Humanities Miusskaya Ploshchad korpus 6, Moscow Russia, 125047 Honorary Professor, University of Exeter Queen's Building, The Queen's Drive Streatham Campus, Exeter, EX4 4QJ Summary: The paper attempts to reveal the affinities between skaldic panegyric poetry and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle poem on the ‘Redemption of the Five Boroughs’ included into four manuscripts (Parker, Worcester and both Abingdon) for the year 942. The thirteen lines of the Chronicle poem are laden with toponyms and ethnonyms, prompting scholars to suggest that its main function is mnemonic. However comparison with skaldic drápur points to the communicative aim of the lists of toponyms and ethnonyms, whose function is to mark the restoration of the space defining the historical significance of Edmund’s victory. The Chronicle poem unites the motifs of glory, spatial conquest and protection of land which are also present in Sighvat’s Knútsdrápa (SkP I 660. 9. 1-8), bearing thematic, situational, structural and functional affinity with the former. Like that of Knútsdrápa, the function of the Chronicle poem is to glorify the ruler by formally reconstructing space. The poem, which, unlike most Anglo-Saxon poetry, is centred not on a past but on a contemporary event, is encomium regis, traditional for skaldic poetry. ‘The Redemption of the Five Boroughs’ can be called an Anglo-Saxon equivalent of erfidrápa, directed to posterity and ensuring eternal fame for the ruler who reconstructed the spatial identity of his kingdom. -

Bury St Edmunds June 2018

June 2018 Bury St Edmunds You said... We did... Community Protection Notice Complaints regarding drug served on residents stopping use causing anti social them having visitors to the behaviour in a residential property. Anti social area. behaviour has now ceased. Responding to issues in your community PCSO Chivers responded to reports of drug dealing taking place in a residential area by carrying out patrols in the area. He identified a suspect who was stopped and found to be in possession of a quantity of controlled drugs. PCSO Howell was approached by a resident living near to a school regarding parking problems at the end of the school day. She liased with the school and identified an area that was more suitable to park. The school advised parents to park in the alternative area which has decreased the parking issue for the resident. Future events Making the community safer The future events that your SNT are Bury ST Edmunds SNT will be taking part in Crucial Crew at the beginning involved in, and will give you an of July 2018. This event is organised to enable young people to learn how to opportunity to chat to them to raise keep themselves safe whilst at home and also when out in the community. your concerns are: PC Fox has taken the role of Community Engagement Officer in Bury St 11/6/18 11:00 am Meet Up Edmunds and will be looking at new ways to engage with the public, this will mondays Boosh Bar include face to face meetings as well as using social networks. -

1. Parish : Stanton

1. Parish : Stanton Meaning: Homestead/village on stony ground 2. Hundred: Blackbourn Deanery: Blackburne (–1972), Ixworth (1972–) Union: Thingoe (1836–1907), Bury St Edmunds (1907–1930) RDC/UDC: (W. Suffolk) Thingoe RD (–1974), St Edmundsbury DC (1974–) Other administrative details: Possible union between the parishes of Stanton All Saints and Stanton St. John the Baptist 17th cent. Blackbourn Petty Sessional Division Bury St Edmunds County Court District 3. Area: 3,319 acres (1912) 4. Soils: Mixed: a. Slowly permeable seasonally water-logged fine loam over clay b. Deep fine loam soils with slowly permeable subsoils and slight seasonal water-logging. Some fine/coarse loams over clay. Some deep well drained coarse loam over clay, fine loam and sandy soils 5. Types of farming: 1086 14 acres meadow, wood for 18 pigs, 2 cobs, 3 cattle, 28 pigs, 52 sheep, 30 goats 1283 517 quarters to crops (4,136 bushels), 72 head horse, 244 cattle, 112 pigs, 395 sheep* 1500–1640 Thirsk: Wood-pasture region, mainly pasture, meadow, engaged in rearing and dairying with some pig keeping, horse breeding and poultry. Crops mainly barley with some wheat, rye, oats, peas, vetches, hops and occasionally hemp. 1818 Marshall: Course of crops varies usually including summer fallow in preparation for corn products 1937 Main crops: Wheat, barley, oats, turnips 1969 Trist: More intensive cereal growing and sugar beet. 1 * ‘A Suffolk Hundred in 1283’, by E. Powell 1910. Concentrates on Blackbourn Hundred. Gives land usage, livestock and the taxes paid. 6. Enclosure: 1350–1600 Evidence suggest early enclosures in southern sector 1785 1st enclosure bill rejected by freeholders Note: 75% of parish enclosed by 1780’s 1800 831 acres enclosed under Private Act of Lands 1798 ‘Opposition to Enclosure in a Suffolk Village’, by D. -

Lordship of Bretts (Also Known As Bretts Place)

Lordship of Bretts (also known as Bretts Place) Parish/ Aveley Principal Victoria County County Essex Source Histories Date History of Lordship Monarchs 871 Creation of the English Monarchy Alfred the Great 871-899 Edward Elder 899-924 Athelstan 924-939 Edmund I 939-946 Edred 946-955 Edwy 955-959 Edgar 959-975 Edward the Martyr 975-978 Ethelred 978-1016 Edmund II 1016 Canute 1016-1035 Harold I 1035-1040 Harthacnut 1040-1042 Pre 1066 Ulstan (or Wulfstan) is holding one hide in Kenningtons that Edward the Confessor 1042-1066 will form the Manor of Bretts. Harold II 1066 1066 Norman Conquest- Battle of Hastings William I 1066-1087 1066 William the Conqueror gives the Manor to Swein of Essex. 1086 Domesday 1086 At Domesday the Manor was held in Overlordship by Lewin as part of the Honour of Rayleigh. William II 1087-1100 Henry I 1100-35 Stephen 1135-54 Henry II 1154-89 Richard I 1189-99 Early 13th The Manor is named by the Bret family who are the demesne John 1199-1216 Century tenants 1212 Hugh le Bret is holding ¼ knight’s fee in Kenningtons. 1215 Magna Carta Henry III 1216-72 1215-1217 First Barons War 1239-1248 Second Barons War 1267 Hugh le Bret or his son and heir die leaving the Manor to John le Bret. © Copyright Manorial Counsel Limited 2018 Lordship of Bretts (also known as Bretts Place) Date History of Lordship Monarchs 1298 John dies and his son and heir Simon succeeds him. The Edward I 1272-1307 Manor comprises 238a. -

Church Farm Lane Thelnetham

Church Farm Lane Thelnetham Guide Price £400,000 The Pleasance Church Farm Lane | Thelnetham | Diss | IP22 1JY Bury St. Edmunds 17 miles, Diss 8 miles, Cambridge 45 miles A superbly presented detached bungalow tucked away down a quiet private lane with wonderful views over open countryside Entrance Hall | Cloakroom | Reception/Dining Room | Fitted Kitchen | 3 Bedrooms | Family Bathroom | En-suite Bathroom | Garage | Ample Parking to Front | Rear Garden | Views Over Open Countryside | Quiet Private Country Lane | Oil Fired Central Heating | 0.31 Acres (s.t.s) The Pleasance The Pleasance is situated in a quiet, tucked away and peaceful location. Within the large entrance hall there are a range of cupboards as well as doorways leading off to most of the bedrooms as well as a family bathroom which benefits from a mainly lawned and has a greenhouse, shed and base in the far principal rooms including the modern fitted cloakroom. The modern suite comprising panelled bath with electric shower right hand corner for a summerhouse. However what must reception/dining room benefits from an open brick fireplace over, pedestal wash hand basin and low flush WC plus tiled be considered one of the main features of the rear garden is and wood mantel surround. There are also glazed double walls and floor. the superb views it affords over open countryside. doors which lead out to the side garden and sliding doors which lead out to the rear garden. From the reception/dining Outside Location room there is a doorway leading into the fitted kitchen which The front of the property is accessed via a five bar gate Thelnetham is situated on the Suffolk/Norfolk border with overlooks the rear garden. -

West Suffolk Commiss Map V5

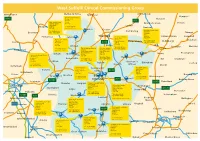

West Suffolk Clinical Commissioning Group Welney Wimblington Methwold Hythe Mundford Attleborough Hempnall Brandon Medical Practice A141 31 High Street Bunwell Brandon A11 Lakenheath Surgery Suffolk 135 High Street IP27 0AQ New Buckenham Shelton Lakenheath Larling Littleport Suffolk Tel: 01842 810388 Fax: 01842 815750 Banham IP27 9EP Brandon Croxton Botesdale Health Centre Tel: 01842 860400 East Harling Back Hills Downham Fax: 01842 862078 Botesdale Alburgh Diss Prickwillow Lakenheath Thetford Dr Hassan & Partners Norfolk Pulham St Mary Redenhall 10 The Chase IP22 1DW Market Cross Surgery Stanton Mendham Ely 7 Market Place Bury St Edmunds Garboldisham Tel: 01379 898295 Dickleburgh Sutton Mildenhall A134 Suffolk Fax: 01379 890477 Suffolk IP31 2XA IP28 7EG Eriswell Euston Diss Tel: 01359 251060 Brockdish Metfield Tel: 01638 713109 The Guildhall and Barrow The Swan Surgery Fax: 01359 252328 Scole Haddenham Fax: 01638 718615 Surgery Northgate Street Lower Baxter Street Bury St Edmunds Bury St Edmunds Suffolk Botesdale Fressingfield Isleham Mildenhall Suffolk IP33 1AE Brome The Rookery Medical Centre IP33 1ET The Rookery Tel: 01284 770440 Stanton Newmarket Barton Mills Tel: 01284 701601 Fax: 01284 723565 Eye Stradbroke Suffolk Fax: 01284 702943 CB8 8NW Wicken Fordham Walsham le Ingham Gislingham Laxfield Tel: 01638 665711 Ixworth Willows Occold Cottenham Fax: 01638 561280 Victoria Surgery Fornham All The Health Centre Burwell Victoria Street Heath Road Bury St Edmunds Saints A143 Woolpit Waterbeach Suffolk SuffolkBacton IP33 3BB IP30 9QU Histon -

SCHOOL ADDRESS HEADTEACHER Phone Number Website Email

SCHOOL LIST BY TOWN SEPTEMBER 2020 ADDRESS HEADTEACHER Phone SCHOOL Website email address number Acton CEVCP School Lambert Drive Acton Sudbury CO10 0US Mrs Julie O'Neill 01787 http://www.acton.suffolk.sch.uk [email protected] 377089 Bardwell CoE Primary School School Lane Bardwell Bury St Edmunds IP31 1AD Mr Rob Francksen 01359 http://www.tilian.org.uk/ [email protected] 250854 Barnham CEVCP School Mill Lane Barnham Thetford IP24 2NG Mrs Amy Arnold 01842 http://www.barnham.suffolk.sch.uk/ [email protected] 890253 Barningham CEVCP School Church Road Barningham Bury St Edmunds IP31 1DD Mrs Frances Parr 01359 http://www.barningham.suffolk.sch.uk/ [email protected] 221297 Barrow CEVCP School Colethorpe Lane Barrow Bury St Edmunds IP29 5AU Mrs Helen Ashe 01284 http://barrowcevcprimaryschool.co.uk/ [email protected] 810223 Bawdsey CEVCP School School Lane Bawdsey Woodbridge IP12 3AR Mrs Katie Butler 01394 http://www.bawdsey.suffolk.sch.uk/ [email protected] 411365 Bedfield CEVCP School Bedfield Woodbridge IP13 7EA Mrs Martine Sills 01728 http://www.bedfieldschool.co.uk/ [email protected] 628306 Benhall: St Mary’s CEVCP School School Lane Benhall Saxmundham IP17 1HE Mrs Katie Jenkins 01728 http://www.benhallschool.co.uk/ [email protected] 602407 Bentley CEVCP School Church Road Bentley Ipswich IP9 2BT Mrs Joanne Austin 01473 http://www.bentleycopdock.co.uk/ [email protected] 310253 Botesdale : St Botolph’s CEVCP Back Hills Botesdale Diss IP22 1DW Mr -

OLAF CUARAN and ST EDITH: a VIEW of TENTH CENTURY TIES BETWEEN NORTHUMBERLAND,YORK and DUBLIN by Michael Anne Guido1

PAGAN SON OF A SAINT:OLAF CUARAN AND ST.EDITH -455- PAGAN SON OF A SAINT:OLAF CUARAN AND ST EDITH: A VIEW OF TENTH CENTURY TIES BETWEEN NORTHUMBERLAND,YORK AND DUBLIN by Michael Anne Guido1 ABSTRACT Though much has been written about Olaf Cuaran little is still known of his origins and his exact place in tenth century history. He has often been confused with his cousin Olaf Guthfrithsson in the early annals and chroniclers. Even his nickname of ‘Cuaran’ is debated as to its exact meaning. He became a legendary figure when he was incorporated into the twelfth century chanson of Havelok the Dane. The focus of this paper is to examine the life and ancestry of Olaf as it is presented in the Northumbrian Chronicle, Irish Annals and several pre-fourteenth century English histories with particular attention upon the dating and origins of each source, as well as debunking myths that have grown around Olaf and his mother. Foundations (2008) 2 (6): 455-476 © Copyright FMG and the author 1. Introduction The period between the late eighth and mid tenth centuries saw one of the largest changes in medieval British history. In this 150 year span England became one nation not a series of kingdoms. Scotland unified southern regions into the kingdom of Alba to protect themselves from the vast northern provinces inhabited by invaders. Ireland became more trade oriented2 (Hudson, 2005) and nationalism flared in Eire for the first time. All these changes occurred in response to the coming of the Northmen, the fierce raiders who came to plunder, kill and enslave the natives of these lands. -

The Thurston & Ixworth

THE THURSTON & IXWORTH Issue 27 January 2021 Delivered from 29/12/20 Also covering Thurston - Ixworth - Bardwell AAdvertisingdvertising SSales:ales: 0012841284 559292 449191 wwww.flww.fl yyeronline.co.ukeronline.co.uk The Flyer From your MP Jo Churchill on bigger premises. We have some year, I am keen for us to make 2021 of excellent Suffolk Cheese, Suffolk wonderful traders across Suffolk, and I the Year of the High Street. Putting brewed beer and cracking Suffolk Pork would encourage constituents to visit the heart back into the centre of our often draws many shoppers on to high as many as possible. communities. Our high streets have streets and into our eateries in our towns and villages. faced unprecedented challenges in I understand that during the pandemic the past few years, and ultimately the many more of us became reliant on Living in Suffolk means we can pandemic has unfortunately hastened online shopping as a necessity, due to sometimes be truly spoilt with the the demise of several well-known the lockdown. However, we are now quality and abundance of locally brands. Nevertheless, new businesses able to visit our shops, restaurants, sourced goods. My mission in 2021 are appearing and many of them cafes and bars in person, all who have is to be a shop Suffolk, shop local exciting small independent traders. worked hard to ensure they have champion, encouraging as many a safe COVID secure environment. Whether on our high streets in Bury individuals as I can to buy from local On my many visits to businesses St Edmunds, Stowmarket or Needham retailers and producers in order to across the constituency I have been Market or out and about at some keep our rural economies energised For the start of a new decade, 2020 impressed by the level of ingenuity of the hidden gems dotted around and our community spirit vibrant.