A Decision Analysis for Sampling and Treating Infected Diabetic Foot Ulcers ISSN 1366-5278 Feedback Your Views About This Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Infant Antibiotic Exposure Search EMBASE 1. Exp Antibiotic Agent/ 2

Infant Antibiotic Exposure Search EMBASE 1. exp antibiotic agent/ 2. (Acedapsone or Alamethicin or Amdinocillin or Amdinocillin Pivoxil or Amikacin or Aminosalicylic Acid or Amoxicillin or Amoxicillin-Potassium Clavulanate Combination or Amphotericin B or Ampicillin or Anisomycin or Antimycin A or Arsphenamine or Aurodox or Azithromycin or Azlocillin or Aztreonam or Bacitracin or Bacteriocins or Bambermycins or beta-Lactams or Bongkrekic Acid or Brefeldin A or Butirosin Sulfate or Calcimycin or Candicidin or Capreomycin or Carbenicillin or Carfecillin or Cefaclor or Cefadroxil or Cefamandole or Cefatrizine or Cefazolin or Cefixime or Cefmenoxime or Cefmetazole or Cefonicid or Cefoperazone or Cefotaxime or Cefotetan or Cefotiam or Cefoxitin or Cefsulodin or Ceftazidime or Ceftizoxime or Ceftriaxone or Cefuroxime or Cephacetrile or Cephalexin or Cephaloglycin or Cephaloridine or Cephalosporins or Cephalothin or Cephamycins or Cephapirin or Cephradine or Chloramphenicol or Chlortetracycline or Ciprofloxacin or Citrinin or Clarithromycin or Clavulanic Acid or Clavulanic Acids or clindamycin or Clofazimine or Cloxacillin or Colistin or Cyclacillin or Cycloserine or Dactinomycin or Dapsone or Daptomycin or Demeclocycline or Diarylquinolines or Dibekacin or Dicloxacillin or Dihydrostreptomycin Sulfate or Diketopiperazines or Distamycins or Doxycycline or Echinomycin or Edeine or Enoxacin or Enviomycin or Erythromycin or Erythromycin Estolate or Erythromycin Ethylsuccinate or Ethambutol or Ethionamide or Filipin or Floxacillin or Fluoroquinolones -

Title 16. Crimes and Offenses Chapter 13. Controlled Substances Article 1

TITLE 16. CRIMES AND OFFENSES CHAPTER 13. CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES ARTICLE 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS § 16-13-1. Drug related objects (a) As used in this Code section, the term: (1) "Controlled substance" shall have the same meaning as defined in Article 2 of this chapter, relating to controlled substances. For the purposes of this Code section, the term "controlled substance" shall include marijuana as defined by paragraph (16) of Code Section 16-13-21. (2) "Dangerous drug" shall have the same meaning as defined in Article 3 of this chapter, relating to dangerous drugs. (3) "Drug related object" means any machine, instrument, tool, equipment, contrivance, or device which an average person would reasonably conclude is intended to be used for one or more of the following purposes: (A) To introduce into the human body any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; (B) To enhance the effect on the human body of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; (C) To conceal any quantity of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; or (D) To test the strength, effectiveness, or purity of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state. (4) "Knowingly" means having general knowledge that a machine, instrument, tool, item of equipment, contrivance, or device is a drug related object or having reasonable grounds to believe that any such object is or may, to an average person, appear to be a drug related object. -

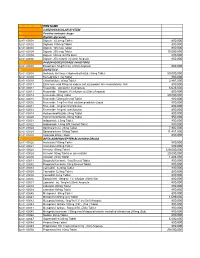

National Code Item Name 1

NATIONAL CODE ITEM NAME 1 CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM 1A Positive inotropic drugs 1AA Digtalis glycoside 02-01-00001 Digoxin 62.5mcg Tablet 800,000 02-01-00002 Digitoxin 100mcg Tablet 800,000 02-01-00003 Digoxin 125 mcg Tablet 800,000 02-01-00004 Digoxin 250 mcg Tablet 15,000,000 02-01-00005 Digoxin 50mcg /ml PG Elixir 800,000 02-01-00006 Digoxin 250 mcg/ml inj (2ml) Ampoule 800,000 1AB PHOSPHODIESTERASE INHIBITORS 02-01-00007 Enoximone 5mg/1ml inj (20ml) Ampoule 800,000 1B DIURETICS 02-01-00008 Amiloride Hcl 5mg + Hydrochlorthiazide 50mg Tablet 50,000,000 02-01-00009 Bumetanide 1 mg Tablet 800,000 02-01-00010 Chlorthalidone 50mg Tablet 2,867,000 02-01-00011 Ethacrynic acid 50mg as sodium salt inj (powder for reconstitution) Vial 800,000 02-01-00012 Frusemide 20mg/2ml inj Ampoule 6,625,000 02-01-00013 Frusemide 10mg/ml,I.V.infusion inj (25ml) Ampoule 800,000 02-01-00014 Frusemide 40mg Tablet 20,000,000 02-01-00015 Frusemide 500mg Scored Tablet 800,000 02-01-00016 Frusemide 1mg/1ml Oral solution peadiatric Liquid 800,000 02-01-00017 Frusemide 4mg/ml Oral Solution 800,000 02-01-00018 Frusemide 8mg/ml oral Solution 800,000 02-01-00019 Hydrochlorothiazide 25mg Tablet 800,000 02-01-00020 Hydrochlorothiazide 50mg Tablet 950,000 02-01-00021 Indapamide 2.5mg Tablet 800,000 02-01-00022 Indapamide 1.5mg S/R Coated Tablet 800,000 02-01-00023 Spironolactone 25mg Tablet 7,902,000 02-01-00024 Spironolactone 100mg Tablet 11,451,000 02-01-00025 Xipamide 20mg Tablet 800,000 1C BETA-ADRENOCEPTER BLOCKING DRUGS 02-01-00026 Acebutolol 100mg Tablet 800,000 02-01-00027 Acebutolol 200mg Tablet 800,000 02-01-00028 Atenolol 100mg Tablet 120,000,000 02-01-00029 Atenolol 50mg Tablet or (scored tab) 20,000,000 02-01-00030 Atenolol 25mg Tablet 1,483,000 02-01-00031 Bisoprolol fumarate 5mg Scored Tablet 800,000 02-01-00032 Bisoprolol fumarate 10mg Scored Tablet 800,000 02-01-00033 Carvedilol 6.25mg Tablet 800,000 02-01-00034 Carvedilol 12.5mg Tablet 800,000 02-01-00035 Carvedilol 25mg Tablet 800,000 02-01-00036 Esmolol Hcl 10mg/ml I.V. -

Transdermal Drug Delivery Device Including An

(19) TZZ_ZZ¥¥_T (11) EP 1 807 033 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: A61F 13/02 (2006.01) A61L 15/16 (2006.01) 20.07.2016 Bulletin 2016/29 (86) International application number: (21) Application number: 05815555.7 PCT/US2005/035806 (22) Date of filing: 07.10.2005 (87) International publication number: WO 2006/044206 (27.04.2006 Gazette 2006/17) (54) TRANSDERMAL DRUG DELIVERY DEVICE INCLUDING AN OCCLUSIVE BACKING VORRICHTUNG ZUR TRANSDERMALEN VERABREICHUNG VON ARZNEIMITTELN EINSCHLIESSLICH EINER VERSTOPFUNGSSICHERUNG DISPOSITIF D’ADMINISTRATION TRANSDERMIQUE DE MEDICAMENTS AVEC COUCHE SUPPORT OCCLUSIVE (84) Designated Contracting States: • MANTELLE, Juan AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR Miami, FL 33186 (US) HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC NL PL PT RO SE SI • NGUYEN, Viet SK TR Miami, FL 33176 (US) (30) Priority: 08.10.2004 US 616861 P (74) Representative: Awapatent AB P.O. Box 5117 (43) Date of publication of application: 200 71 Malmö (SE) 18.07.2007 Bulletin 2007/29 (56) References cited: (73) Proprietor: NOVEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. WO-A-02/36103 WO-A-97/23205 Miami, FL 33186 (US) WO-A-2005/046600 WO-A-2006/028863 US-A- 4 994 278 US-A- 4 994 278 (72) Inventors: US-A- 5 246 705 US-A- 5 474 783 • KANIOS, David US-A- 5 474 783 US-A1- 2001 051 180 Miami, FL 33196 (US) US-A1- 2002 128 345 US-A1- 2006 034 905 Note: Within nine months of the publication of the mention of the grant of the European patent in the European Patent Bulletin, any person may give notice to the European Patent Office of opposition to that patent, in accordance with the Implementing Regulations. -

Partial Agreement in the Social and Public Health Field

COUNCIL OF EUROPE COMMITTEE OF MINISTERS (PARTIAL AGREEMENT IN THE SOCIAL AND PUBLIC HEALTH FIELD) RESOLUTION AP (88) 2 ON THE CLASSIFICATION OF MEDICINES WHICH ARE OBTAINABLE ONLY ON MEDICAL PRESCRIPTION (Adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 22 September 1988 at the 419th meeting of the Ministers' Deputies, and superseding Resolution AP (82) 2) AND APPENDIX I Alphabetical list of medicines adopted by the Public Health Committee (Partial Agreement) updated to 1 July 1988 APPENDIX II Pharmaco-therapeutic classification of medicines appearing in the alphabetical list in Appendix I updated to 1 July 1988 RESOLUTION AP (88) 2 ON THE CLASSIFICATION OF MEDICINES WHICH ARE OBTAINABLE ONLY ON MEDICAL PRESCRIPTION (superseding Resolution AP (82) 2) (Adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 22 September 1988 at the 419th meeting of the Ministers' Deputies) The Representatives on the Committee of Ministers of Belgium, France, the Federal Republic of Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, these states being parties to the Partial Agreement in the social and public health field, and the Representatives of Austria, Denmark, Ireland, Spain and Switzerland, states which have participated in the public health activities carried out within the above-mentioned Partial Agreement since 1 October 1974, 2 April 1968, 23 September 1969, 21 April 1988 and 5 May 1964, respectively, Considering that the aim of the Council of Europe is to achieve greater unity between its members and that this -

Design, Synthesis, Characterization and Computational Docking Studies of Novel Sulfonamide Derivatives

EXCLI Journal 2018;17:169-180 – ISSN 1611-2156 Received: October 17, 2017, accepted: January 29, 2017, published: February 01, 2018 Original article: DESIGN, SYNTHESIS, CHARACTERIZATION AND COMPUTATIONAL DOCKING STUDIES OF NOVEL SULFONAMIDE DERIVATIVES Hira Saleem1a, Arooma Maryam1a, Saleem Ahmed Bokhari1a, Ayesha Ashiq1, Sadaf Abdul Rauf2, Rana Rehan Khalid1, Fahim Ashraf Qureshi1b, Abdul Rauf Siddiqi1 ⃰ 1 Department of Biosciences, COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Islamabad, Pakistan 2 Department of Computer Science, Fatima Jinnah Women University, The Mall, Rawalpindi a Equal contributions, co-first authors b Shared correspondence: [email protected] ⃰ corresponding author: Abdul Rauf Siddiqi, Department of Biosciences, COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Park Road, Islamabad, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] http://dx.doi.org/10.17179/excli2017-886 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). ABSTRACT This study reports three novel sulfonamide derivatives 4-Chloro-N-[(4-methylphenyl) sulphonyl]-N-propyl ben- zamide (1A), N-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-4-methyl benzene sulfonamide (1B) and 4-methyl-N-(2-nitrophenyl) ben- zene sulfonamide (1C). The compounds were synthesised from starting material 4-methylbenzenesulfonyl chlo- ride and their structure was studied through 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectra. Computational docking was per- formed to estimate their binding energy against bacterial p-amino benzoic acid (PABA) receptor, the dihydrop- teroate synthase (DHPS). The derivatives were tested in vitro for their antimicrobial activity against Gram+ and Gram- bacteria including E. coli, B. subtilis, B. licheniformis and B. linen. 1A was found active only against B. -

Consideration of Antibacterial Medicines As Part Of

Consideration of antibacterial medicines as part of the revisions to 2019 WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for adults (EML) and Model List of Essential Medicines for children (EMLc) Section 6.2 Antibacterials including Access, Watch and Reserve Lists of antibiotics This summary has been prepared by the Health Technologies and Pharmaceuticals (HTP) programme at the WHO Regional Office for Europe. It is intended to communicate changes to the 2019 WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for adults (EML) and Model List of Essential Medicines for children (EMLc) to national counterparts involved in the evidence-based selection of medicines for inclusion in national essential medicines lists (NEMLs), lists of medicines for inclusion in reimbursement programs, and medicine formularies for use in primary, secondary and tertiary care. This document does not replace the full report of the WHO Expert Committee on Selection and Use of Essential Medicines (see The selection and use of essential medicines: report of the WHO Expert Committee on Selection and Use of Essential Medicines, 2019 (including the 21st WHO Model List of Essential Medicines and the 7th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019 (WHO Technical Report Series, No. 1021). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/330668/9789241210300-eng.pdf?ua=1) and Corrigenda (March 2020) – TRS1021 (https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/TRS1021_corrigenda_March2020. pdf?ua=1). Executive summary of the report: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/325773/WHO- MVP-EMP-IAU-2019.05-eng.pdf?ua=1. -

Conjugate and Prodrug Strategies As Targeted Delivery Vectors for Antibiotics † † ‡ Ana V

Review Cite This: ACS Infect. Dis. XXXX, XXX, XXX−XXX pubs.acs.org/journal/aidcbc Signed, Sealed, Delivered: Conjugate and Prodrug Strategies as Targeted Delivery Vectors for Antibiotics † † ‡ Ana V. Cheng and William M. Wuest*, , † Department of Chemistry, Emory University, 1515 Dickey Drive, Atlanta, Georgia 30322, United States ‡ Emory Antibiotic Resistance Center, Emory School of Medicine, 201 Dowman Drive, Atlanta, Georgia 30322, United States ABSTRACT: Innate and developed resistance mechanisms of bacteria to antibiotics are obstacles in the design of novel drugs. However, antibacterial prodrugs and conjugates have shown promise in circumventing resistance and tolerance mechanisms via directed delivery of antibiotics to the site of infection or to specific species or strains of bacteria. The selective targeting and increased permeability and accumu- lation of these prodrugs not only improves efficacy over unmodified drugs but also reduces off-target effects, toxicity, and development of resistance. Herein, we discuss some of these methods, including sideromycins, antibody-directed prodrugs, cell penetrating peptide conjugates, and codrugs. KEYWORDS: oligopeptide, sideromycin, antibody−antibiotic conjugate, cell penetrating peptide, dendrimer, transferrin inding new and innovative methods to treat bacterial F infections comes with many inherent challenges in addition to those presented by the evolution of resistance mechanisms. The ideal antibiotic is nontoxic to host cells, permeates bacterial cells easily, and accumulates at the site of infection at high concentrations. Narrow spectrum drugs are also advantageous, as they can limit resistance development and leave the host commensal microbiome undisturbed.1 However, various resistance mechanisms make pathogenic infections difficult to eradicate: Many bacteria respond to antibiotic pressure by decreasing expression of active transporters and porins2 and 3,4 Downloaded via EMORY UNIV on April 18, 2019 at 12:34:17 (UTC). -

Pharmaceuticals Appendix

)&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE )&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 3 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. Product CAS No. Product CAS No. ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ADAPALENE 106685-40-9 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ADAPROLOL 101479-70-3 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ADEMETIONINE 17176-17-9 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ADENOSINE PHOSPHATE 61-19-8 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ADIBENDAN 100510-33-6 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ADICILLIN 525-94-0 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 ADIMOLOL 78459-19-5 ACAPRAZINE 55485-20-6 ADINAZOLAM 37115-32-5 ACARBOSE 56180-94-0 ADIPHENINE 64-95-9 ACEBROCHOL 514-50-1 ADIPIODONE 606-17-7 ACEBURIC ACID 26976-72-7 ADITEREN 56066-19-4 ACEBUTOLOL 37517-30-9 ADITOPRIME 56066-63-8 ACECAINIDE 32795-44-1 ADOSOPINE 88124-26-9 ACECARBROMAL 77-66-7 ADOZELESIN 110314-48-2 ACECLIDINE 827-61-2 ADRAFINIL 63547-13-7 ACECLOFENAC 89796-99-6 ADRENALONE 99-45-6 ACEDAPSONE 77-46-3 AFALANINE 2901-75-9 ACEDIASULFONE SODIUM 127-60-6 AFLOQUALONE 56287-74-2 ACEDOBEN 556-08-1 AFUROLOL 65776-67-2 ACEFLURANOL 80595-73-9 AGANODINE 86696-87-9 ACEFURTIAMINE 10072-48-7 AKLOMIDE 3011-89-0 ACEFYLLINE CLOFIBROL 70788-27-1 -

A Class-Selective Immunoassay for Sulfonamides Residue Detection in Milk Using a Superior Polyclonal Antibody with Broad Specificity and Highly Uniform Affinity

Article A Class-Selective Immunoassay for Sulfonamides Residue Detection in Milk Using a Superior Polyclonal Antibody with Broad Specificity and Highly Uniform Affinity Chenglong Li 1, Xiangshu Luo 1, Yonghan Li 2, Huijuan Yang 1, Xiao Liang 3, Kai Wen 1, Yanxin Cao 1, Chao Li 1, Weiyu Wang 1, Weimin Shi 1, Suxia Zhang 1, Xuezhi Yu 1,* and Zhanhui Wang 1 1 Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Food Nutrition and Human Health, College of Veterinary Medicine, China Agricultural University, Beijing Key Laboratory of Detection Technology for Animal- Derived Food Safety, Beijing Laboratory of Food Quality and Safety, 100193 Beijing, China; [email protected] (C.L.); [email protected] (X.L.); [email protected] (H.Y.); [email protected] (K.W.); [email protected] (Y.C.); [email protected] (C.L.); [email protected] (W.W.); [email protected] (W.S.); [email protected] (S.Z.); [email protected] (Z.W.) 2 Henan Animal Health Supervision Institute, 450008 Zhengzhou, China; [email protected] 3 College of Veterinary Medicine, Qingdao Agricultural University, 266109 Qingdao, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-10-62734565; Fax: +86-10-62731032 Academic Editors: Patricia Regal and Carlos M. Franco Received: 13 December 2018; Accepted: 24 January 2019; Published: 26 January 2019 Abstract: The development of multianalyte immunoassays with an emphasis on food safety has attracted increasing interest, due to its high target throughput, short detection time, reduced sample consumption, and low overall cost. In this study, a superior polyclonal antibody (pAb) against sulfonamides (SAs) was raised by using a bioconjugate of bovine serum albumin with a rationally designed hapten 4-[(4-aminophenyl) sulfonyl-amino]-2-methoxybenzoic acid (SA10-X). -

Twocases of Severe Bronchiectasis Successfully Treated With

CASE REPORT TwoCases of Severe Bronchiectasis Successfully Treated with a Prolonged Course of Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole Takayuki Honda, Muneharu Hayasaka*, Tsutomu Hachiya*, Keishi Kubo*, Tsutomu Katsuyama and Atsuo Nagata** Twopatients with severe bronchiectasis, one patient without other disease and the other with hyper IgE syndrome, were successfully treated with long-term therapy with low doses oftrimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ).Recurrent respiratory infections with productive cough and high fever were resistant to various antibiotics and often disturbed the patients' activities in daily life. However, they showed marked improvement following TMP-SMZtherapy, which was started for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)infection. MRSAdisappeared some months later, but Pseudomonas aeruginosa appeared again in the sputum. Both patients, however, have remained free from symptomsfor over one year. (Internal Medicine 35: 979-983, 1996) Key words: hyper IgE syndrome, lower respiratory infection, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonasaeruginosa Introduction toms which disturbed his activity in daily life. Hemophilis influenzae and/or Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) It has been reported that trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole were isolated from his sputum. He had received many different (TMP-SMZ) is effective for short-term and long-term use in the antibiotics including ampicillin, piperacillin sodium, treatment of chronic respiratory infections (1, 2). Recently, sultamicillin tosilate, cefazolin sodium, cefotiam hexetil hy- however, TMP-SMZhas not been considered the drug of first drochloride, cefteram pivoxil, clindamycin, ciprofloxacin hy- choice for various bacterial infections due to its side effects and drochloride and ofloxacin. They were sensitive to at least one because of the development of new antibiotics. Wedescribe antibiotic. However,other antibiotics were tried due to repeated here two cases with severe bronchiectasis successfully treated fever. -

Sinusitis (Acute): Antimicrobial Prescribing Guideline Evidence Review

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence APG Sinusitis (acute) Sinusitis (acute): antimicrobial prescribing guideline Evidence review October 2017 Final version Contents Disclaimer The recommendations in this guideline represent the view of NICE, arrived at after careful consideration of the evidence available. When exercising their judgement, professionals are expected to take this guideline fully into account, alongside the individual needs, preferences and values of their patients or service users. The recommendations in this guideline are not mandatory and the guideline does not override the responsibility of healthcare professionals to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual patient, in consultation with the patient and/or their carer or guardian. Local commissioners and/or providers have a responsibility to enable the guideline to be applied when individual health professionals and their patients or service users wish to use it. They should do so in the context of local and national priorities for funding and developing services, and in light of their duties to have due regard to the need to eliminate unlawful discrimination, to advance equality of opportunity and to reduce health inequalities. Nothing in this guideline should be interpreted in a way that would be inconsistent with compliance with those duties. NICE guidelines cover health and care in England. Decisions on how they apply in other UK countries are made by ministers in the Welsh Government, Scottish Government, and Northern Ireland Executive. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. Copyright © NICE 2017. All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. Contents Contents Contents .............................................................................................................................