In Photographic Work by Andy Warhol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Low-Cost Conversion of the Polaroid MD-4 Land Camera to a Digital Gel Documentation System

J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 67 (2006) 1–5 www.elsevier.com/locate/jbbm Short note Low-cost conversion of the Polaroid MD-4 land camera to a digital gel documentation system Timothy G. Porch *, John E. Erpelding USDA, Agricultural Research Service, Tropical Agriculture Research Station, 2200 Pedro Albizu Campos Ave., Suite 201, Mayaguez, Puerto Rico, 00680-5470 Received 21 April 2005; received in revised form 15 November 2005; accepted 15 December 2005 Abstract A simple, inexpensive design is presented for the rapid conversion of the popular MD-4 Polaroid land camera to a high quality digital gel documentation system. Images of ethidium bromide stained DNA gels captured using the digital system were compared to images captured on Polaroid instant film. Resolution and sensitivity were enhanced using the digital system. In addition to the low cost and superior image quality of the digital system, there is also the added convenience of real-time image viewing through the swivel LCD of the digital camera, wide flexibility of gel sizes, accurate automatic focusing, variable image resolution, and consistent ease of use and quality. Images can be directly imported to a computer by using the USB port on the digital camera, further enhancing the potential of the digital system for documentation, analysis, and archiving. The system is appropriate for use as a start-up gel documentation system and for routine gel analysis. Published by Elsevier B.V. Keywords: Digital camera; Electrophoresis; Gel imaging; Gel documentation 1. Introduction Numerous molecular biology applications rely on the capture of images for the analysis of nucleic acids or proteins. -

Ten Top Tips for Photography and Videography

PROGRESSIVE APPROACHES TO TI.IE WORK AT I{AND CRU ELTY I NVESTIGATIONS Ten TopTipsfor Good Ph otog ra p hy, Vid eo g ra p hy Document incidents oJ animal cruelty and neglect more eJJectioely by f ollowing tbese belpJul bints. By Ceoffrey L. Handy { ruelty investigators lor the -) Check with local prosecutors Thilor the mix of photographs g - ? SPCA ol Texas in Dallas have Zo and ludges to find out what J o and video to the case at hand. Ltaken to wearing basebali they like and what they dont. Ask Photographs (or "stills") are general- caps on the job. No, they're not be- questions: Do they have any special ly best for stark images, whereas ing unprofessional. Instead, they're requirements or preferences, such as video is best lor capt.uring move- practicing how to use $2,000 worth including dates on photographs, re- ments and sounds. For a ten-month- of undercover surveillance equip- quiring certification by the devel- old German shepherd with a chain ment purchased with a donation oper that the photos were not al- embedded in her neck, for example, from Mary Kay Cosmetics. The tered in any way, or a preference that a few color stills are your best bet. equipment includes a video camera at least one photograph shows the For an animal who vocalizes his dis- small enough to fit inside a baseball investigator on the scene? (To be on tress, supplement the stills with a cap and a f-inch Magnavox televi- the safe side, you should take those minute or two of video. -

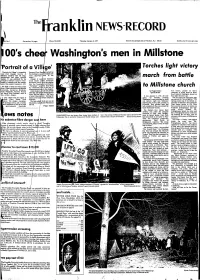

T"° Anklin News-Record

T"° anklin news-recorD one section, 24 pages / Phone 725-3300 Thursday, January 6, 1977 Second class postage paid at Princeton, N.J. 08540 I!,No. 1 $4.50 a year/t5 cents per copy O0’s chee Washington’s men in Millstone a ViI ge’ Torches light victory 0Portrait"Portrait of a Village"is a carefullyof Somerset Court HouLppreaehed the segched 50-page hislory of Revolutionary Millstone, complete with 100 .maps, most important photographs and other graphic county’." march from battle iisplays. It was published by the Chapter II deal Somerset mrough’s Historic District Com- Court House ant American nissinn to coincide with the reenact- Revolution,and it’ ~ on this chapter nent of the events of January3, 1777. that the ial production The book is edited by Diane Jones "Turnabout" was Hap Heins to Millstone church ;tiney. Othercontributors are Marllyn Sr. contributed a in the way of information and s to this chapter. :antarella, Katharine Erickson, Otherchapters ¢LI with the periods by Peggy Roeske Van Doren, played by Terry 3rnce Marganoff, Patricia Nivlson Special Writer Jamieson, at whose house on River md Barrie Alan Peterson, each of who.n wrote a chapter. times. The final c is "250 Years Road General Washington stayed on of Local ChurchI tracing the It was January 3, 1T/7, all over that night 200 years ago. ’ ~pter I deals with the origins of history of the DuReform Church in again. On Monday evening The play gave the imnression that ~erset Court House tnow Millstone. Washingten’s army marched by torch war was not all *’fun and games."The The chapter concludes: The booksells can be and lantern light into Millstone opening scene was of the British ca- forge, farms, and a variety obtained b following the victory that morningat cups(ion of Millstone (then Somerset all industriesas wellas its legal 359-1361. -

D2492609215cd311123628ab69

Acknowledgements Publisher AN Cheongsook, Chairperson of KOFIC 206-46, Cheongnyangni-dong, Dongdaemun-gu. Seoul, Korea (130-010) Editor in Chief Daniel D. H. PARK, Director of International Promotion Department Editors KIM YeonSoo, Hyun-chang JUNG English Translators KIM YeonSoo, Darcy PAQUET Collaborators HUH Kyoung, KANG Byeong-woon, Darcy PAQUET Contributing Writer MOON Seok Cover and Book Design Design KongKam Film image and still photographs are provided by directors, producers, production & sales companies, JIFF (Jeonju International Film Festival), GIFF (Gwangju International Film Festival) and KIFV (The Association of Korean Independent Film & Video). Korean Film Council (KOFIC), December 2005 Korean Cinema 2005 Contents Foreword 04 A Review of Korean Cinema in 2005 06 Korean Film Council 12 Feature Films 20 Fiction 22 Animation 218 Documentary 224 Feature / Middle Length 226 Short 248 Short Films 258 Fiction 260 Animation 320 Films in Production 356 Appendix 386 Statistics 388 Index of 2005 Films 402 Addresses 412 Foreword The year 2005 saw the continued solid and sound prosperity of Korean films, both in terms of the domestic and international arenas, as well as industrial and artistic aspects. As of November, the market share for Korean films in the domestic market stood at 55 percent, which indicates that the yearly market share of Korean films will be over 50 percent for the third year in a row. In the international arena as well, Korean films were invited to major international film festivals including Cannes, Berlin, Venice, Locarno, and San Sebastian and received a warm reception from critics and audiences. It is often said that the current prosperity of Korean cinema is due to the strong commitment and policies introduced by the KIM Dae-joong government in 1999 to promote Korean films. -

N7637 Pigeon Rd

1 - N7637 Pigeon Rd. – Lots of baby & toddler toys (standing and ride-on toys, rocking horse electronic w/music & lights). Lots of girls clothes (newborn to 24 mo/2T most purchased new 2-5 years ago). Glider & footstool barely used. 5 wood doors with skeleton key locks. Set of 3 glass-top tables (2 end & 2 coffee) metal painted cream/tan. Men’s sweaters, sweatshirts, jeans (sz L), women’s sweaters, jeans, shirts (sz M) & pants (sz 6-9). Scrubs sets all occasions like new/fun patterns (sz S-M), women’s jackets, clothing, etc (sz S). 2 high-back bar stools, chandelier & light fixtures & misc items for home. Tornado foosball table like new (will not physically be at the sale but will have a photo and can arrange to look at). Children’s board books, girl crib set w/mobile, comforter (never used), sheets, dust ruffle, bumper pads pink butterflies. 2 crib mattresses, waterproof mattress protectors, crib sheets, railing padded protector, Safety 1 st baby gate (white plastic). Several white sconces, various tools, girl 2-wheel bike Disney Princes 14”, jogging & other strollers, 2 diaper champs, pizza oven, outdoor infant dolphin swing, mesh safety rails, 2 potty chairs, Sony baby monitors, & more! 2 - N7663 Pigeon Rd. – Baby boy clothes, chair, toys, costumes, home décor, maternity clothes and more. All priced to sell! 3 - N7770 State Park Rd. – 3-Family Rummage Sale: Two 10 ft. x 20 ft. tan colored party tents, “This End Up” loveseat, couch and desk set-rustic looking and built to last. DVDs albums, golf clubs, bar lights, metal poles for bird houses, graduation decorations (orange, black & purple), household and décor items, queen size comforter with pillow shams, drapes and valances, real estate items including realtor motivational tapes/CDs, display stands, etc. -

Andy Warhol and the Dawn of Modern-Day Celebrity Culture 113

Andy Warhol and the Dawn of Modern-Day Celebrity Culture 113 Alicja Piechucka Fifteen Minutes of Fame, Fame in Fifteen Minutes: Andy Warhol and the Dawn of Modern-Day Celebrity Culture Life imitates art more than art imitates life. –Oscar Wilde Celebrity is a mask that eats into the face. –John Updike If someone conducted a poll to choose an American personality who best embodies the 1960s, Andy Warhol would be a strong candidate. Pop art, the movement Warhol is typically associated with, flourished in the 60s. It was also during that decade that Warhol’s career peaked. From 1964 till 1968 his studio, known as the Silver Factory, became not just a hothouse of artistic activity, but also the embodiment of the zeitgeist: the “sex, drugs and rock’n’roll” culture of the period with its penchant for experimentation and excess, the revolution in morals and sexuality (Korichi 182–183, 206–208). The seventh decade of the twentieth century was also the time when Warhol opened an important chapter in his painterly career. In the early sixties, he started executing celebrity portraits. In 1962, he completed series such as Marilyn and Red Elvis as well as portraits of Natalie Wood and Warren Beatty, followed, a year later, by Jackie and Ten Lizes. In total, Warhol produced hundreds of paintings depicting stars and famous personalities. This major chapter in his artistic career coincided, in 1969, with the founding of Interview magazine, a monthly devoted to cinema and to the celebration of celebrity, in which Warhol was the driving force. The aim of this essay is to analyze Warhol’s portraits of famous people in terms of how they anticipate the celebrity-obsessed culture in which we now live. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

I – Introduction

QUEERING PERFORMATIVITY: THROUGH THE WORKS OF ANDY WARHOL AND PERFORMANCE ART by Claudia Martins Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts in Gender Studies CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2008 I never fall apart, because I never fall together. Andy Warhol The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back again CEU eTD Collection CONTENTS ILLUSTRATIONS..........................................................................................................iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.................................................................................................v ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................vi CHAPTER 1 - Introduction .............................................................................................7 CHAPTER 2 - Bringing the body into focus...................................................................13 CHAPTER 3 - XXI century: Era of (dis)embodiment......................................................17 Disembodiment in Virtual Spaces ..........................................................18 Embodiment Through Body Modification................................................19 CHAPTER 4 - Subculture: Resisting Ajustment ............................................................22 CHAPTER 5 - Sexually Deviant Bodies........................................................................24 CHAPTER 6 - Performing gender.................................................................................29 -

FUSION 2018 the Craft Behind the Image Saturday, May 5Th, 2018 River Rock Casino Resort Richmond, BC

Whatever Your Interests, We Have a Show for You! FUSION 2018 The Craft Behind the Image Saturday, May 5th, 2018 River Rock Casino Resort Richmond, BC Immerse yourself in photography! Fusion 2018 is a full day of speakers, on-stage demos and an Industry Expo. Hear talks on travel photography, portraits, lighting, printing your own images, and more. The Industry Expo will run from 10AM to 5PM with displays and demos of the latest equipment. www.beauphoto.com/fusion2018 An Exhibition of Instant Images April 4th - May 13th, 2018 Opening April 4th, 6 - 8PM Science World - Aurizon Atrium www.beauphoto.com/instant Join the show! Submissions open until March 20th! MAGAZINE Beau Newsletter - March 2018 Beau Photo is On The Move! • The New Fujifilm X-H1 Camera - In Stock and in Rentals! • Fujifilm XF 80mm f/2.8R LM OIS WR Macro lens • Canon Speedlite 470EX-AI • Contax T Cameras • All About Fujifilm Instax Cameras • New Lastolite Skylite Rapid System • Renaissance Stock Albums Sale • more... BEAU NEWS MARCH 2018 Beau Photo Is On The Move... City of Vancouver Archives - CVA 99-3766 - Arrow Transfer fleet of trucks We are excited to announce that the rumours are true: Beau Photo will be on the move in late 2018! This is something that’s been in the works for well over a year, and the plan is now coming together. We are in the process of securing a new location and once everything is finalized, we’ll let you know. With even more developments scheduled in the area of our current location, the time is ripe for us to head elsewhere and we’re sure you won’t miss the parking struggle! Once we have finalized the where and when, you’ll want to “Save the Date” for the big Welcome to our New Store Party we have planned! We are all excited about designing a new space in a new location and please note, the plans include not having the shipping/receiving area and staff kitchen in the middle of the shop this time around! But don’t worry, our unique, laid-back shopping experience will still be there. -

Sister Corita's Summer of Love

Sister Corita’s Summer of Love Sister Corita’s Summer of Love Sister Corita teaching at Immaculate Heart College, Los Angeles, ca. 1967. Sister Corita Kent is an artists’ artist. In 2008, Corita’s sensibilities were fostered by Corita’s work is finally getting its due in contemporaries Colin McCahon and Ed Ruscha, while travelling through the United States doing and advanced the concerns of the Second the United States, with numerous recent shows, and by the Wellington Media Collective and research, I kept encountering her work on the Vatican Council (1962–5), commonly known but she remains under-recognised outside the Australian artist Marco Fusinato. Similarly, for walls of artists I was visiting and fell in love with as ‘Vatican II’, which moved to modernise the US. Despite our having the English language the City Gallery Wellington show, their Chief it. Happily, one of those artists steered me toward Catholic Church and make it more relevant to in common—and despite its resonance with Curator Robert Leonard has developed his own the Corita Art Center, in Los Angeles, where I contemporary society. Among other things, it Colin McCahon’s—her work is little known in sidebar exhibition, including works by McCahon could learn more. Our show Sister Corita’s Summer advocated changes to traditional liturgy, including New Zealand. So, having already included her in and Ruscha again, New Zealanders Jim Speers, of Love resulted from that visit and offers a journey conducting Mass in the vernacular instead several exhibitions in Europe, when I began my Michael Parekowhai, and Michael Stevenson, through her life and work. -

Warhol, Andy (As Filmmaker) (1928-1987) Andy Warhol

Warhol, Andy (as filmmaker) (1928-1987) Andy Warhol. by David Ehrenstein Image appears under the Creative Commons Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Courtesy Jack Mitchell. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com As a painter Andy Warhol (the name he assumed after moving to New York as a young man) has been compared to everyone from Salvador Dalí to Norman Rockwell. But when it comes to his role as a filmmaker he is generally remembered either for a single film--Sleep (1963)--or for works that he did not actually direct. Born into a blue-collar family in Forest City, Pennsylvania on August 6, 1928, Andrew Warhola, Jr. attended art school at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh. He moved to New York in 1949, where he changed his name to Andy Warhol and became an international icon of Pop Art. Between 1963 and 1967 Warhol turned out a dizzying number and variety of films involving many different collaborators, but after a 1968 attempt on his life, he retired from active duty behind the camera, becoming a producer/ "presenter" of films, almost all of which were written and directed by Paul Morrissey. Morrissey's Flesh (1968), Trash (1970), and Heat (1972) are estimable works. And Bad (1977), the sole opus of Warhol's lover Jed Johnson, is not bad either. But none of these films can compare to the Warhol films that preceded them, particularly My Hustler (1965), an unprecedented slice of urban gay life; Beauty #2 (1965), the best of the films featuring Edie Sedgwick; The Chelsea Girls (1966), the only experimental film to gain widespread theatrical release; and **** (Four Stars) (1967), the 25-hour long culmination of Warhol's career as a filmmaker. -

William Morris & Andy Warhol

MODERN ART EVENTS OXFORD THE YARD TOURS The Factory Floor Wednesday 7 January, 1pm Wednesday to Saturday, 12-5pm, weekly Sally Shaw, Head of Programme at Modern Art Oxford For the duration of Love is Enough, the Yard will discusses the development of the exhibition and be transformed into a ‘Factory Floor’ in homage to introduces key works. William Morris and Andy Warhol’s prolific production techniques. Each week a production method or craft Wednesday 21 January, 1pm skill will be demonstrated by a specialist. Ben Roberts, Curator of Education & Public Programmes at Modern Art Oxford discusses The Factory Floor is a rare opportunity to see creative education, collaboration and participation in relation to processes such as metal casting, dry stone walling, the work of Morris and Warhol. bookbinding, weaving and tapestry. LOVE IS Wednesday 4 February, 1pm These drop-in sessions provide a chance to meet Paul Teigh, Production Manager at Modern Art Oxford makers and craftspeople working with these processes discusses manufacturing and design processes today. Please see website for further details. inherent in the work of Morris and Warhol. TALKS Wednesday 18 February, 1pm Artist talk Ciara Moloney, Curator of Exhibitions & Projects Saturday 6 December, 6pm Free, booking essential at Modern Art Oxford discusses key works in the ENOUGH Jeremy Deller in conversation with Ralph Rugoff, exhibition and their influence on artistic practices Director, Hayward Gallery, London. today. Perspectives: Myth Thursday 15 January, 7pm BASEMENT: PERFORMANCE A series of short talks on myths and myth making from Live in the Studio the roots of medieval tales to our collective capacity December 2014 – February 2015 for fiction and how myths are made in contemporary A short series of performance projects working with culture.