4. Goyder Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Savanna Responses to Feral Buffalo in Kakadu National Park, Australia

Ecological Monographs, 77(3), 2007, pp. 441–463 Ó 2007 by the Ecological Society of America SAVANNA RESPONSES TO FERAL BUFFALO IN KAKADU NATIONAL PARK, AUSTRALIA 1,2,6 3,4,5 5 4,5 5 AARON M. PETTY, PATRICIA A. WERNER, CAROLINE E. R. LEHMANN, JAN E. RILEY, DANIEL S. BANFAI, 4,5 AND LOUIS P. ELLIOTT 1Department of Environmental Science and Policy, University of California, Davis, California 95616 USA 2Tropical Savannas Cooperative Research Centre, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, NT 0909 Australia 3The Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia 4Faculty of Education, Health and Science. Charles Darwin University, Darwin, NT 0909, Australia 5School for Environmental Research, Charles Darwin University. Darwin, NT 0909, Australia Abstract. Savannas are the major biome of tropical regions, spanning 30% of the Earth’s land surface. Tree : grass ratios of savannas are inherently unstable and can be shifted easily by changes in fire, grazing, or climate. We synthesize the history and ecological impacts of the rapid expansion and eradication of an exotic large herbivore, the Asian water buffalo (Bubalus bubalus), on the mesic savannas of Kakadu National Park (KNP), a World Heritage Park located within the Alligator Rivers Region (ARR) of monsoonal north Australia. The study inverts the experience of the Serengeti savannas where grazing herds rapidly declined due to a rinderpest epidemic and then recovered upon disease control. Buffalo entered the ARR by the 1880s, but densities were low until the late 1950s when populations rapidly grew to carrying capacity within a decade. In the 1980s, numbers declined precipitously due to an eradication program. -

Issue 31, June 2019

From the President I recently experienced a great sense of history and admiration for early Spanish and Portuguese navigators during visits to historic sites in Spain and Portugal. For example, the Barcelona Maritime Museum, housed in a ship yard dating from the 13th century and nearby towering Christopher Columbus column. In Lisbon the ‘Monument to the Discoveries’ reminds you of the achievements of great explorers who played a major role in Portugal's age of discovery and building its empire. Many great navigators including; Vasco da Gama, Magellan and Prince Henry the Navigator are commemorated. Similarly, in Gibraltar you are surrounded by military and naval heritage. Gibraltar was the port to which the badly damaged HMS Victory and Lord Nelson’s body were brought following the Battle of Trafalgar fought less than 100 miles to the west. This experience was also a reminder of the exploits of early voyages of discovery around Australia. Matthew Flinders, to whom Australians owe a debt of gratitude features in the June edition of the Naval Historical Review. The Review, with its assessment of this great navigator will be mailed to members in early June. Matthew Flinders grave was recently discovered during redevelopment work on Euston Station in London. Similarly, this edition of Call the Hands focuses on matters connected to Lieutenant Phillip Parker King RN and his ship, His Majesty’s Cutter (HMC) Mermaid which explored north west Australia in 1818. The well-known indigenous character Bungaree who lived in the Port Jackson area at the time accompanied Parker on this voyage. Other stories in this edition are inspired by more recent events such as the keel laying ceremony for the first Arafura Class patrol boat attended by the Chief of Navy. -

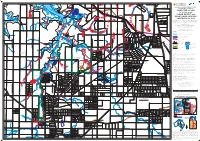

FLOOD EXTENT and PEAK FLOOD SURFACE CONTOURS for 2100

707500E 710000E 712500E 715000E 717500E 720000E 722500E 725000E 11 1 0 2 26 23 18 Middle Arm Road 19 22 BLACKMORE 17 19 27 25 18 1 NOONAMAH 2 19 ELIZABETH and BLACKMORE RIVER 23 3 5 24 20 CATCHMENTS — Sheet 2 25 4 20 4 COMPUTED 1% AEP RIVER 3 Aquiculture Farm Ponds 26 26 21 21 22 (1 in 100 year) 5 Middle Arm Boat Ramp 25 6 24 7 1 23 FLOOD EXTENT and 2 8 22 16 14 18 23 22 9 15 20 13 21 PEAK FLOOD SURFACE 24 10 1 19 12 17 20 23 CONTOURS for 2100 1 3 4 18 25 6 11 21 24 This map shows the Q100 flood and floodway extents caused by a 1% Annual 1.5 10 2 19 1.25 5 Exceedance Probability (AEP) Flood event over the Elizabeth and Blackmore 8600000N 8600000N 1.25 2 25 Keleson Road River Catchments. The extent of flooding shown on this map is indicative only, 17 Middle Arm Road 2 2 Strauss Field 26 hence, approximate. This map is available for sale from: 3 1.5 9 26 3 27 Land Information Centre, 1 1 8 27 3 1 2 Department of Lands, Planning and the Environment 3 1 3 7 16 1.5 1 3rd Floor NAB House, 71 Smith Street, Darwin, Northern Territory, 0800 28 29 29 Finn Road Finn 1.25 T: (08) 8995 5300 Email: [email protected] 6 30 2 28 31 GPO Box 1680, Darwin, Northern Territory, 0801. 3 31 15 4 5 14 27 33 This map is also available online at: 7 32 30 RIVER 6 7 8 10 35 www.nt.gov.au/floods http://nrmaps.nt.gov.au 9 13 11 12 8 26 32 Legend 2.5 4 5 25 34 3 24 6 Flood extent 3 7 24 8 23 Floodway, depth >2 metres (or velocity x depth > 1) 9 23 22 3 1.25 10 Peak flood surface contour, metres AHD 3 22 10.5 21 Creek channel / flow direction 21 20 Limit of flood mapping -

"AUSTRALIA and HER NAVIGATORS" [By the President, COMMANDER NORMAN S

78 PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS "AUSTRALIA AND HER NAVIGATORS" [By the President, COMMANDER NORMAN S. PIXLEY, C.M.G., M.B.E., V.R.D., Kt.O.N., F.R.Hist.S.Q.] (Read at a Meeting of the Society on 24 September 1970.) Joseph Conrad in his writings, refers to "The mysteriously born traditions of seacraft, command, and unity in an occu pation in which men's lives depend on each other." Still true today, how much more was this so with the mariners of long ago, who sailed in smaU ships for thousands of lonely leagues through unknown seas, for on them alone rested the safety of the ship and all on board. Dr. Johnson wrote "No man will be a saUor who has con trivance to get himself into jaU, for being in a ship is being in a jail with the chance of being drowned." There was more than an element of truth in this, for the seaman who refused to sail could be clapped in jail; whUst THE PRESIDENT, COMMANDER NORMAN S PIXLEY 79 those who did sail faced months in a confined space with acute discomfort, severe punishment at times, and provisions and water which deteriorated as the voyage proceeded. Scurvy kiUed more than storm and shipwreck until James Cook in his first voyage proved that it could be prevented. Clothing was rarely changed, the sailor coming wet to his hammock from his watch on deck in bad weather. Rats and cockroaches lived and thrived amongst the pro visions, adding to the problems of hygiene and health. -

Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks

Department for Environment and Heritage Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks Part of the Far North & Far West Region (Region 13) Historical Research Pty Ltd Adelaide in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd Lyn Leader-Elliott Iris Iwanicki December 2002 Frontispiece Woolshed, Cordillo Downs Station (SHP:009) The Birdsville & Strzelecki Tracks Heritage Survey was financed by the South Australian Government (through the State Heritage Fund) and the Commonwealth of Australia (through the Australian Heritage Commission). It was carried out by heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd, in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd, Lyn Leader-Elliott and Iris Iwanicki between April 2001 and December 2002. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia and they do not accept responsibility for any advice or information in relation to this material. All recommendations are the opinions of the heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd (or their subconsultants) and may not necessarily be acted upon by the State Heritage Authority or the Australian Heritage Commission. Information presented in this document may be copied for non-commercial purposes including for personal or educational uses. Reproduction for purposes other than those given above requires written permission from the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia. Requests and enquiries should be addressed to either the Manager, Heritage Branch, Department for Environment and Heritage, GPO Box 1047, Adelaide, SA, 5001, or email [email protected], or the Manager, Copyright Services, Info Access, GPO Box 1920, Canberra, ACT, 2601, or email [email protected]. -

Cooksland in North-Eastern Australia

This is a digital copy of a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by Google as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. It has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books are our gateways to the past, representing a wealth of history, culture and knowledge that's often difficult to discover. Marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in this file - a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Usage guidelines Google is proud to partner with libraries to digitize public domain materials and make them widely accessible. Public domain books belong to the public and we are merely their custodians. Nevertheless, this work is expensive, so in order to keep providing this resource, we have taken steps to prevent abuse by commercial parties, including placing technical restrictions on automated querying. We also ask that you: + Make non-commercial use of the files We designed Google Book Search for use by individuals, and we request that you use these files for personal, non-commercial purposes. + Refrain from automated querying Do not send automated queries of any sort to Google's system: If you are conducting research on machine translation, optical character recognition or other areas where access to a large amount of text is helpful, please contact us. -

Journal of a Voyage Around Arnhem Land in 1875

JOURNAL OF A VOYAGE AROUND ARNHEM LAND IN 1875 C.C. Macknight The journal published here describes a voyage from Palmerston (Darwin) to Blue Mud Bay on the western shore of the Gulf of Carpentaria, and back again, undertaken between September and December 1875. In itself, the expedition is of only passing interest, but the journal is worth publishing for its many references to Aborigines, and especially for the picture that emerges of the results of contact with Macassan trepangers along this extensive stretch of coast. Better than any other early source, it illustrates the highly variable conditions of communication and conflict between the several groups of people in the area. Some Aborigines were accustomed to travelling and working with Macassans and, as the author notes towards the end of his account, Aboriginal culture and society were extensively influenced by this contact. He also comments on situations of conflict.1 Relations with Europeans and other Aborigines were similarly complicated and uncertain, as appears in several instances. Nineteenth century accounts of the eastern parts of Arnhem Land, in particular, are few enough anyway to give another value. Flinders in 1802-03 had confirmed the general indications of the coast available from earlier Dutch voyages and provided a chart of sufficient accuracy for general navigation, but his contact with Aborigines was relatively slight and rather unhappy. Phillip Parker King continued Flinders' charting westwards from about Elcho Island in 1818-19. The three early British settlements, Fort Dundas on Melville Island (1824-29), Fort Wellington in Raffles Bay (1827-29) and Victoria in Port Essington (1838-49), were all in locations surveyed by King and neither the settlement garrisons nor the several hydrographic expeditions that called had any contact with eastern Arnhem Land, except indirectly by way of the Macassans. -

Our Cultural Collections a Guide to the Treasures Held by South Australia’S Collecting Institutions Art Gallery of South Australia

Our Cultural Collections A guide to the treasures held by South Australia’s collecting institutions Art Gallery of South Australia. South Australian Museum. State Library of South Australia. Car- rick Hill. History SA. Art Gallery of South Aus- tralia. South Australian Museum. State Library of South Australia. Carrick Hill. History SA. Art Gallery of South Australia. South Australian Museum. State Library of South Australia. Car- rick Hill. History SA. Art Gallery of South Aus- Published by Contents Arts South Australia Street Address: Our Cultural Collections: 30 Wakefield Street, A guide to the treasures held by Adelaide South Australia’s collecting institutions 3 Postal address: GPO Box 2308, South Australia’s Cultural Institutions 5 Adelaide SA 5001, AUSTRALIA Art Gallery of South Australia 6 Tel: +61 8 8463 5444 Fax: +61 8 8463 5420 South Australian Museum 11 [email protected] www.arts.sa.gov.au State Library of South Australia 17 Carrick Hill 23 History SA 27 Artlab Australia 43 Our Cultural Collections A guide to the treasures held by South Australia’s collecting institutions The South Australian Government, through Arts South Our Cultural Collections aims to Australia, oversees internationally significant cultural heritage ignite curiosity and awe about these collections comprising millions of items. The scope of these collections is substantial – spanning geological collections, which have been maintained, samples, locally significant artefacts, internationally interpreted and documented for the important art objects and much more. interest, enjoyment and education of These highly valuable collections are owned by the people all South Australians. of South Australia and held in trust for them by the State’s public institutions. -

Records Territory Jul

August 2007 Records Territory No 32 Northern Territory Archives Service Newsletter From the Director Northern Territory Welcome to Records Territory. History Grants The spotlight for this issue is on aspects of life in We congratulate the following recipients for completion Darwin in the 1950s. This is to complement the theme of their research in the last few months for which they selected by the National Trust for the recent Heritage received part or total assistance from the NT History Festival. Grants Program. In this issue we also bring you features about some See page 14 for details of the 2007 History Grants of our fascinating archives collections, and we focus recipients and their research. on current projects and activities under way in our Darwin and Alice Springs offi ces. There are also Barry M Allwright, Rivers of Rubies, the history of the features about the interesting range of research which ruby rush in Central Australia Service Archives Northern Territory our clients are undertaking and some of the success Pam Oliver, Empty North: the Japanese presence and stories encouraged by the NT History Grants program. Australian reactions, 1860 to 1942 On the government recordkeeping front, we provide Judy A Cotton, Borroloola, isolated and interesting, information about initiatives achieved or in the 1885 - 2005 planning stages for continuing delivery of the electronic Colin De La Rue, “…for the good of His Majesty’s document and records management system. Service” The archaeology of Fort Dundas, 1824 - 1829 (thesis 2006) As I write this, an administrative reorganisation of the NTAS is impending, and we’ll tell you all about that in Gayle Carroll, Virgins’ retreat, a terrifi c tale of intrigue the next issue. -

Stokes.J01.Cs .Pdf (Pdf, 98.54

*************************************************************** * * * WARNING: Please be aware that some caption lists contain * * language, words or descriptions which may be considered * * offensive or distressing. * * These words reflect the attitude of the photographer * * and/or the period in which the photograph was taken. * * * * Please also be aware that caption lists may contain * * references to deceased people which may cause sadness or * * distress. * * * *************************************************************** Scroll down to view captions STOKES.J01.CS (000056247-000056306) Hunting, wildlife, portraits in Northern Territory Date taken : various dates; Arnhem Land, Darwin region and near Islands ++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Item no.: STOKES.J01.CS-000056247 Date/Place taken: Title: Historical map of Northern Australia by Peter Goss published in 1669 Photographer/Artist: Access: Conditions apply Notes: ++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Item no.: STOKES.J01.CS-000056248 Date/Place taken: Title: Historical map of Arnheims [Arnhem] Land published by W Faden published in 1802 Photographer/Artist: Access: Conditions apply Notes: ++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Item no.: STOKES.J01.CS-000056249 Date/Place taken: Title: [Book page] - view of north east coast of Arnhem Land by W. Westfall published 1803 Photographer/Artist: Access: Conditions apply Notes: ++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Item no.: STOKES.J01.CS-000056250 Date/Place taken: Title: [Cropped book page] - view of north east coast of Arnhem Land by W. Westfall published 1803 Photographer/Artist: -

Industry Policies of the South Australian Government†

The Otemon Journal of Australian Studies, vol.37, pp.171−188, 2011 171 Industry Policies of the South Australian Government† Koshiro Ota Hiroshima Shudo University 1. Introduction Australia is a country rich in minerals and land. According to the Department of Foreign Af- fairs and Trade (DFAT) (2010), Australia’s major merchandise exports in 2010 were minerals (30.1%), fuels (28.8%), gold (6.2%), and processed and unprocessed food (10.6%; the figures in parentheses are shares in total export value). This trade structure is the reason Australia is often called a ‘lucky state’. However, manufactured goods composed 14.7% of total merchandise export value, and elaborately transformed manufactures, such as pharmaceutical products, machinery for specialised industries, and road motor vehicles and parts, composed more than 60% of the total manufactured goods export value. Adelaide, the capital city of South Australia with population of 1.2 million, traditionally has a strong manufacturing sector. The 2006 Census showed that its em- ployment rate in the manufacturing sector was the highest of all capital cities at 15%. However, the reduction of tariffs on imported goods has exposed the manufacturing industries in Adelaide to severe international competition,1) and led to the reduction or discontinuation of pro- duction. Recently, the strong Australian dollar has further challenged manufacturing companies (hereafter, we denote the Australian dollar (or A$) simply as the dollar (or $) unless special men- tion is needed). According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2011), ‘South Australia’s manufacturing industry showed negative growth in both employment and production between 2000 −01 and 2009−10’. -

Weddell Design Forum a Summary of the Outcomes of a Workshop to Explore Issues + Options for the Future City of Weddell

Weddell Design Forum A Summary of the Outcomes of a Workshop to explore Issues + Options for the future City of Weddell 27 September - 1 October 2010 Darwin Convention Centre, Darwin A report to the Northern Territory Government from the consultant leaders of the Weddell Design Forum NOVEMBER 2010 Sustainable, Liveable Tropical, Contents Foreword By 2018, Palmerston will be at capacity, vacant blocks around Introduction 1 Darwin will be developed. Darwin is one of the fastest growing cities in Australia. While much of this growth will be absorbed by The Site + Growth Context 2 in-fill development in Darwin’s existing suburbs and new Palmerston suburbs, we have to start planning now for the future growth of the Community Input 4 Territory. Special Interest Groups 5 Our children and grandchildren will want to live in houses that are in-tune with our environment. They will want to live in a community Key Issues for Weddell 6 that connects people with schools, work, shops and recreation Scenarios 9 facilities that are within walking distance rather than a car ride away. Design Outcomes 10 Achieving this means starting now with good land use planning, setting aside strategic transport corridors and considering the Traffic + Streets 26 physical and social services that will be needed. Indicative Development Costs 27 The Weddell Conference and Design Forum gave us a blank canvas Conclusions + Recommendations 28 on which to paint ideas, consider the picture and recalibrate what we had created. Weddell Design Team 30 It was a unique opportunity rarely experienced by our planning professionals and engineers to consider the views of the community, the imagination of our youth and to engage with such a range of experts.