Species Fact Sheet for Umatilla Megomphix

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

San Gabriel Chestnut ESA Petition

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR PETITION TO THE U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE TO PROTECT THE SAN GABRIEL CHESTNUT SNAIL UNDER THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT © James Bailey CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY Notice of Petition Ryan Zinke, Secretary U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Greg Sheehan, Acting Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Paul Souza, Director Region 8 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Southwest Region 2800 Cottage Way Sacramento, CA 95825 [email protected] Petitioner The Center for Biological Diversity is a national, nonprofit conservation organization with more than 1.3 million members and supporters dedicated to the protection of endangered species and wild places. http://www.biologicaldiversity.org Failure to grant the requested petition will adversely affect the aesthetic, recreational, commercial, research, and scientific interests of the petitioning organization’s members and the people of the United States. Morally, aesthetically, recreationally, and commercially, the public shows increasing concern for wild ecosystems and for biodiversity in general. 1 November 13, 2017 Dear Mr. Zinke: Pursuant to Section 4(b) of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. §1533(b), Section 553(3) of the Administrative Procedures Act, 5 U.S.C. § 553(e), and 50 C.F.R. §424.14(a), the Center for Biological Diversity and Tierra Curry hereby formally petition the Secretary of the Interior, through the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (“FWS”, “the Service”) to list the San Gabriel chestnut snail (Glyptostoma gabrielense) as a threatened or endangered species under the Endangered Species Act and to designate critical habitat concurrently with listing. -

Oreohelices of Utah, I. Rediscovery of the Uinta Mountainsnail, Oreohelix Eurekensis Uinta Brooks, 1939 (Stylommatophora: Oreohelicidae)

Western North American Naturalist Volume 60 Number 4 Article 13 10-31-2000 Oreohelices of Utah, I. Rediscovery of the Uinta mountainsnail, Oreohelix eurekensis uinta Brooks, 1939 (Stylommatophora: Oreohelicidae) George V. Oliver Utah Natural Heritage Program, Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Salt Lake City, Utah William R. Bosworth III Utah Natural Heritage Program, Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Salt Lake City, Utah Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan Recommended Citation Oliver, George V. and Bosworth, William R. III (2000) "Oreohelices of Utah, I. Rediscovery of the Uinta mountainsnail, Oreohelix eurekensis uinta Brooks, 1939 (Stylommatophora: Oreohelicidae)," Western North American Naturalist: Vol. 60 : No. 4 , Article 13. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan/vol60/iss4/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western North American Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Western North American Naturalist 60(4), © 2000, pp. 451–455 OREOHELICES OF UTAH, I. REDISCOVERY OF THE UINTA MOUNTAINSNAIL, OREOHELIX EUREKENSIS UINTA BROOKS, 1939 (STYLOMMATOPHORA: OREOHELICIDAE) George V. Oliver1 and William R. Bosworth III1 ABSTRACT.—Oreohelix eurekensis uinta had not been found since its original discovery and had never been reported as a living taxon, and this had led to speculation that it is extinct. However, searches for O. e. uinta had been confounded by multiple errors in the original definition of the type locality. The type locality has now been relocated and is here redefined, and O. -

Factors Affecting the Structure and Distribution of Terrestrial Pulmonata

Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science Volume 73 Annual Issue Article 60 1966 Factors Affecting the Structure and Distribution of Terrestrial Pulmonata Charles G. Atkins Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1966 Iowa Academy of Science, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias Recommended Citation Atkins, Charles G. (1966) "Factors Affecting the Structure and Distribution of Terrestrial Pulmonata," Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science, 73(1), 408-416. Available at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias/vol73/iss1/60 This Research is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa Academy of Science at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science by an authorized editor of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Atkins: Factors Affecting the Structure and Distribution of Terrestrial P Factors Affecting the Structure and Distribution of Terrestrial Pulmonata CHARLES G. ATKINS Abstracts Soil CaCO. levels were determined for six ecosystems in Washtenaw and Wayne Counties, Michigan and in Linn County, Iowa; and correlation between these results and the shell thickness of certain terrestrial snails was made. Species used were Anguispira alternata ( Say), Triodopsis multilineata (Say), and T. albolabris (Say). Two ecosystems had high caco. levels ( 120-144 ppm), three had intermedi ate levels ( 93-99ppm) and one had a low level ( 40 ppm). 'Width/thickness ratios of live and cast shells showed that those in high calcium ecosystems had thicker shells than those in low calcium ecosystems, though there were large de viations in the thickness values. -

ED45E Rare and Scarce Species Hierarchy.Pdf

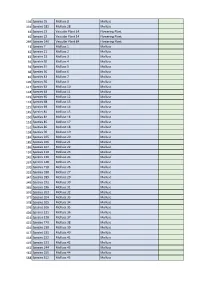

104 Species 55 Mollusc 8 Mollusc 334 Species 181 Mollusc 28 Mollusc 44 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 45 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 269 Species 149 Vascular Plant 84 Flowering Plant 13 Species 7 Mollusc 1 Mollusc 42 Species 21 Mollusc 2 Mollusc 43 Species 22 Mollusc 3 Mollusc 59 Species 30 Mollusc 4 Mollusc 59 Species 31 Mollusc 5 Mollusc 68 Species 36 Mollusc 6 Mollusc 81 Species 43 Mollusc 7 Mollusc 105 Species 56 Mollusc 9 Mollusc 117 Species 63 Mollusc 10 Mollusc 118 Species 64 Mollusc 11 Mollusc 119 Species 65 Mollusc 12 Mollusc 124 Species 68 Mollusc 13 Mollusc 125 Species 69 Mollusc 14 Mollusc 145 Species 81 Mollusc 15 Mollusc 150 Species 84 Mollusc 16 Mollusc 151 Species 85 Mollusc 17 Mollusc 152 Species 86 Mollusc 18 Mollusc 158 Species 90 Mollusc 19 Mollusc 184 Species 105 Mollusc 20 Mollusc 185 Species 106 Mollusc 21 Mollusc 186 Species 107 Mollusc 22 Mollusc 191 Species 110 Mollusc 23 Mollusc 245 Species 136 Mollusc 24 Mollusc 267 Species 148 Mollusc 25 Mollusc 270 Species 150 Mollusc 26 Mollusc 333 Species 180 Mollusc 27 Mollusc 347 Species 189 Mollusc 29 Mollusc 349 Species 191 Mollusc 30 Mollusc 365 Species 196 Mollusc 31 Mollusc 376 Species 203 Mollusc 32 Mollusc 377 Species 204 Mollusc 33 Mollusc 378 Species 205 Mollusc 34 Mollusc 379 Species 206 Mollusc 35 Mollusc 404 Species 221 Mollusc 36 Mollusc 414 Species 228 Mollusc 37 Mollusc 415 Species 229 Mollusc 38 Mollusc 416 Species 230 Mollusc 39 Mollusc 417 Species 231 Mollusc 40 Mollusc 418 Species 232 Mollusc 41 Mollusc 419 Species 233 -

Interior Columbia Basin Mollusk Species of Special Concern

Deixis l-4 consultants INTERIOR COLUMl3lA BASIN MOLLUSK SPECIES OF SPECIAL CONCERN cryptomasfix magnidenfata (Pilsbly, 1940), x7.5 FINAL REPORT Contract #43-OEOO-4-9112 Prepared for: INTERIOR COLUMBIA BASIN ECOSYSTEM MANAGEMENT PROJECT 112 East Poplar Street Walla Walla, WA 99362 TERRENCE J. FREST EDWARD J. JOHANNES January 15, 1995 2517 NE 65th Street Seattle, WA 98115-7125 ‘(206) 527-6764 INTERIOR COLUMBIA BASIN MOLLUSK SPECIES OF SPECIAL CONCERN Terrence J. Frest & Edward J. Johannes Deixis Consultants 2517 NE 65th Street Seattle, WA 98115-7125 (206) 527-6764 January 15,1995 i Each shell, each crawling insect holds a rank important in the plan of Him who framed This scale of beings; holds a rank, which lost Would break the chain and leave behind a gap Which Nature’s self wcuid rue. -Stiiiingfieet, quoted in Tryon (1882) The fast word in ignorance is the man who says of an animal or plant: “what good is it?” If the land mechanism as a whole is good, then every part is good, whether we understand it or not. if the biota in the course of eons has built something we like but do not understand, then who but a fool would discard seemingly useless parts? To keep every cog and wheel is the first rule of intelligent tinkering. -Aido Leopold Put the information you have uncovered to beneficial use. -Anonymous: fortune cookie from China Garden restaurant, Seattle, WA in this “business first” society that we have developed (and that we maintain), the promulgators and pragmatic apologists who favor a “single crop” approach, to enable a continuous “harvest” from the natural system that we have decimated in the name of profits, jobs, etc., are fairfy easy to find. -

86 Animal Miraculum Discovery of Living Anguispira Alternata (Say

Discovery of Living Anguispira alternata (Say, 1816) (Discidae: Gastropoda) in Louisiana, USA Russell L. Minton*, Erin L. Basiger, and Casey B. Nolan Department of Biology, University of Louisiana at Monroe, 700 University Avenue, Monroe, LA 71209-0520, USA (Accepted January 29, 2010) Of the 13 recognized species of Anguispira in the US, 2 are listed as occurring in Louisiana (NatureServe 2009). (A) Anguispira alternata (Say, 1819) is a pulmonate land snail found throughout the eastern US, including states bordering the Mississippi River to the west (Hubricht 1985). The other species, A. strongylodes (Pfeiffer, 1854), is found across the southern US, with a range that narrowly overlaps A. alternata at its northern boundary. The shell of A. strongylodes differs from that of A. alternata by lacking streaks along the base and the umbilicus and by having smaller spots along the shell periphery (Pilsbry 1948). Hubricht (1985) listed only fossil A. alternata as occurring in Louisiana and Mississippi, while NatureServe (2009) lists it as extirpated in both states. Pilsbry viewed strongylodes as a weakly differentiated subspecies of A. alternata endemic to east-central Texas, although Hubricht (1960) later elevated strongylodes to species status and established its currently recognized range (Hubricht 1985). During a recent survey of Black Bayou Lake National Wildlife Refuge (32.6°N, 92.04°W) in Monroe, LA, we collected (B) a number of living and dead specimens that matched the original description and other published images of A. alternata and not A. strongylodes. These specimens possessed the color patterns described by Pilsbry (1948), most notably prominent spots on the periphery and streaks on the underside that separate A. -

(Calidivitrina) Chyuluensis (Figs 1-3) by a Long

BASTERIA, 69:147-156, 2005 A new species of Vitrina (Gastropoda, Pulmonata, Vitrinidae) from Kenya with a discussion of the genus in East Africa B. Verdcourt Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond,Surrey, TW9 3AB, U.K. Vitrina is described from the It has rather chyuluensis spec. nov. Chyulu Hills, Kenya. a large shell and characterised fine is by a long spermathecal duct, very plicae between distal and is proximal parts of the penis, and a three-ridgedjaw. The description followed by a discussion on the classification ofEast African species of Vitrina and on the variation in characters proba- of taxonomic at level. The is concluded bly significance specific paper by some comments on naming Vitrina from East Africa. Key words: Gastropoda, Pulmonata, Vitrinidae, Vitrina, taxonomy, Kenya, East Africa. INTRODUCTION Quentin Luke during a botanical collecting expedition to the Chyulu Hills, Kajiado District, Kenya (02°39' S, 37°52' E), collected some helicarionoidsnails in montane forest on recent volcanic lava. I at first assumed that the seven specimens in the sample belonged the than the others. showed be to same species, one more mature Dissection it to a Chlamydarion Van Mol, 1970, which I could not match with described species. In order to features dissected further find had different verify certain I a specimen only to it a totally and fact four other anatomy was in a Vitrina as were specimens. One other was a juvenile I been Chlamydarion. have for many years attempting to make some sense of the East African of Vitrina and dissected from the species Draparnaud, 1801, numerous specimens East African highlands. -

Euconulus Alderi Gray a Land Snail

Euconulus alderi, Page 1 Euconulus alderi Gray A land snail State Distribution Photo by Matthew Barthel and Jeffery C. Nekola Best Survey Period Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Status: State listed as Special Concern are smaller, have a more shiny luster, and a darker shell color. Also, the microscopic spiral lines on the base of Global and state ranks: G3Q/S2 the shell are stronger than the radial striations. This is reversed in E. fulvus (Nekola 1998). For more Family: Helicarionidae information on identifying land snails, see Burch and Jung (1988) pages 155-158 or Burch and Pearce (1990) Synonyms: none pages 211-218. Total range: The global range of Euconulus alderi Best survey time: Surveys for E. alderi are best includes Ireland, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the performed after rain, when the soil and vegetation are United States. Within the U.S. it has been found in moist. During dry periods, a survey site can appear Iowa, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, and completely devoid of snails, while after a rain the same Wisconsin (Frest 1990, NatureServe 2007, Nekola site can be found to contain numerous individuals. 1998). This species was not known from North Temperatures should be warm enough that the ground is America until 1986 when it was discovered in Iowa and not frozen and there is no snow. Dry, hot periods during Wisconsin (Frest 1990, Nekola 1998). mid-summer should be avoided. The best time of day to survey is often in early morning when conditions are State distribution: E. -

Appendix A: Common and Scientific Names for Fish and Wildlife Species Found in Idaho

APPENDIX A: COMMON AND SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR FISH AND WILDLIFE SPECIES FOUND IN IDAHO. How to Read the Lists. Within these lists, species are listed phylogenetically by class. In cases where phylogeny is incompletely understood, taxonomic units are arranged alphabetically. Listed below are definitions for interpreting NatureServe conservation status ranks (GRanks and SRanks). These ranks reflect an assessment of the condition of the species rangewide (GRank) and statewide (SRank). Rangewide ranks are assigned by NatureServe and statewide ranks are assigned by the Idaho Conservation Data Center. GX or SX Presumed extinct or extirpated: not located despite intensive searches and virtually no likelihood of rediscovery. GH or SH Possibly extinct or extirpated (historical): historically occurred, but may be rediscovered. Its presence may not have been verified in the past 20–40 years. A species could become SH without such a 20–40 year delay if the only known occurrences in the state were destroyed or if it had been extensively and unsuccessfully looked for. The SH rank is reserved for species for which some effort has been made to relocate occurrences, rather than simply using this status for all elements not known from verified extant occurrences. G1 or S1 Critically imperiled: at high risk because of extreme rarity (often 5 or fewer occurrences), rapidly declining numbers, or other factors that make it particularly vulnerable to rangewide extinction or extirpation. G2 or S2 Imperiled: at risk because of restricted range, few populations (often 20 or fewer), rapidly declining numbers, or other factors that make it vulnerable to rangewide extinction or extirpation. G3 or S3 Vulnerable: at moderate risk because of restricted range, relatively few populations (often 80 or fewer), recent and widespread declines, or other factors that make it vulnerable to rangewide extinction or extirpation. -

Terrestrial Mollusks of Attu, Aleutian Islands, Alaska BARRY ROTH’ and DAVID R

ARCTK: VOL. 34, NO. 1 (MARCH 1981), P. 43-47 Terrestrial Mollusks of Attu, Aleutian Islands, Alaska BARRY ROTH’ and DAVID R. LINDBERG’ ABSTRACT. Seven species of land mollusk (2 slugs, 5 snails) were collected on Attu in July 1979. Three are circumboreal species, two are amphi-arctic (Palearctic and Nearctic but not circumboreal), and two are Nearctic. Barring chance survival of mollusks in local refugia, the fauna was assembled overwater since deglaciation, perhaps within the last 10 OOO years. Mollusk faunas from Kamchatka to southeastern Alaska all have a Holarctic component. A Palearctic component present on Kamchatka and the Commander Islands is absent from the Aleutians, which have a Nearctic component that diminishes westward. This pattern is similar to that of other soil-dwelling invertebrate groups. RESUM& Sept espbces de mollusques terrestres (2 limaces et 5 escargots) furent prklevkes sur I’ile d’Attu en juillet 1979. Trois sont des espbces circomborkales, deux amphi-arctiques (Palkarctiques et Nkarctiques mais non circomborkales), et deux Nkarctiques. Si I’on excepte la survivance de mollusques due auhasard dans des refuges locaux, cette faune s’est retrouvke de part et d’autre des eauxdepuis la dkglaciation, peut-&re depuis les derniers 10 OOO ans. Les faunes de mollusques de la pkninsule de Kamchatkajusqu’au sud-est de 1’Alaska on toutes une composante Holarctique. Une composante Palkarctique prksente sur leKamchatka et les iles Commandeur ne se retrouve pas aux Alkoutiennes, oil la composante Nkarctique diminue vers I’ouest. Ce patron est similaire il celui de d’autres groupes d’invertkbrks terrestres . Traduit par Jean-Guy Brossard, Laboratoire d’ArchCologie de I’Universitk du Qukbec il Montrkal. -

Gastropoda: Stylommatophora)1 John L

EENY-494 Terrestrial Slugs of Florida (Gastropoda: Stylommatophora)1 John L. Capinera2 Introduction Florida has only a few terrestrial slug species that are native (indigenous), but some non-native (nonindigenous) species have successfully established here. Many interceptions of slugs are made by quarantine inspectors (Robinson 1999), including species not yet found in the United States or restricted to areas of North America other than Florida. In addition to the many potential invasive slugs originating in temperate climates such as Europe, the traditional source of invasive molluscs for the US, Florida is also quite susceptible to invasion by slugs from warmer climates. Indeed, most of the invaders that have established here are warm-weather or tropical species. Following is a discus- sion of the situation in Florida, including problems with Figure 1. Lateral view of slug showing the breathing pore (pneumostome) open. When closed, the pore can be difficult to locate. slug identification and taxonomy, as well as the behavior, Note that there are two pairs of tentacles, with the larger, upper pair ecology, and management of slugs. bearing visual organs. Credits: Lyle J. Buss, UF/IFAS Biology as nocturnal activity and dwelling mostly in sheltered Slugs are snails without a visible shell (some have an environments. Slugs also reduce water loss by opening their internal shell and a few have a greatly reduced external breathing pore (pneumostome) only periodically instead of shell). The slug life-form (with a reduced or invisible shell) having it open continuously. Slugs produce mucus (slime), has evolved a number of times in different snail families, which allows them to adhere to the substrate and provides but this shell-free body form has imparted similar behavior some protection against abrasion, but some mucus also and physiology in all species of slugs. -

Slugs (Of Florida) (Gastropoda: Pulmonata)1

Archival copy: for current recommendations see http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu or your local extension office. EENY-087 Slugs (of Florida) (Gastropoda: Pulmonata)1 Lionel A. Stange and Jane E. Deisler2 Introduction washed under running water to remove excess mucus before placing in preservative. Notes on the color of Florida has a depauparate slug fauna, having the mucus secreted by the living slug would be only three native species which belong to three helpful in identification. different families. Eleven species of exotic slugs have been intercepted by USDA and DPI quarantine Biology inspectors, but only one is known to be established. Some of these, such as the gray garden slug Slugs are hermaphroditic, but often the sperm (Deroceras reticulatum Müller), spotted garden slug and ova in the gonads mature at different times (Limax maximus L.), and tawny garden slug (Limax (leading to male and female phases). Slugs flavus L.), are very destructive garden and greenhouse commonly cross fertilize and may have elaborate pests. Therefore, constant vigilance is needed to courtship dances (Karlin and Bacon 1961). They lay prevent their establishment. Some veronicellid slugs gelatinous eggs in clusters that usually average 20 to are becoming more widely distributed (Dundee 30 on the soil in concealed and moist locations. Eggs 1977). The Brazilian Veronicella ameghini are round to oval, usually colorless, and sometimes (Gambetta) has been found at several Florida have irregular rows of calcium particles which are localities (Dundee 1974). This velvety black slug absorbed by the embryo to form the internal shell should be looked for under boards and debris in (Karlin and Naegele 1958).