Brighton & Hove Historic Character

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

R-Ns/Trash #240 May 2017 Find Us On

BOGGY SHOE The magazine of Brighton Hash House Harriers (twinned with Bangkok Hash House Harriers) R-ns/trash #240 May 2017 Find us on or at http://www.brightonhash.co.uk/ All r*ns are on Mondays meet at 19.30 for 19.40 start unless stated. All directions/ timings are approximate and start from Patcham roundabout A23/A27 junction. DATE #NO ON ON REF HARES 1st May 2017 2028 Paiges Wood Car Park, Haywards Heath 317 247 Keeps It Up & Wildbush Directions: A23 north, A272 to Haywards Heath, left at Dolphin pub and 3rd left Lucastes Avenue. Left at T junction then 2nd right for car park. Est. 20 mins. Bank Holiday run 5.30pm start. 8th May 2017 2029 Red Lion, Ashington 132 158 Wiggy Directions: A27 to Shoreham, A283 north. Left at roundabout stay on A283 past Steyning and take 2nd right for Wiston. Under A24 and pub is on left. Est. 25 mins. 15th May 2017 2030 Stand Up Inn, Lindfield 347 255 Psychlepath Rik Directions: Follow A23 north to Bolney junction with A272. Turn left and back under A23 to Ansty. Stay on A272 until Haywards Heath then left towards the station. Straight on at station roundabout and left at the next into village. First left after pond for village car park. Pub slightly further up. Est. 20 mins. 22nd May 2017 2031 Hampden Arms, South Heighton 452 028 Dildoped Matt Directions: A27 past Lewes. Right at Beddingham roundabout on A26. Take 4th left, signed South Heighton 1/2, follow round to right and pub on left. -

Groundsure Planning

Groundsure Planning Address: Specimen Address Date: Report Date Report Reference: Planning Specimen Your Reference:Planning Specimen Client:Client Report Reference: Planning Specimen Contents Aerial Photo................................................................................................................. 3 1. Overview of Findings................................................................................................. 4 2. Detailed Findings...................................................................................................... 5 Planning Applications and Mobile Masts Map..................................................................... 6 Planning Applications and Mobile Masts Data.................................................................... 7 Designated Environmentally Sensitive Sites Map.............................................................. 18 Designated Environmentally Sensitive Sites.................................................................... 19 Local Information Map................................................................................................. 21 Local Information Data................................................................................................ 22 Local Infrastructure Map.............................................................................................. 32 Local Infrastructure Data.............................................................................................. 33 Education.................................................................................................................. -

Annual Report 2005

The Regency Society of Brighton & Hove ANNUAL REPORT 2005 www.regencysociety.org President The Duke of Grafton KG FSA Vice Presidents Rt. Hon. Lord Briggs FBA Sir John Kingman FRS Chairman Gavin Henderson CBE Vice Chairmen Derek Granger Peter Rose FSA Dr. Michael Ray Audrey Simpson Dr. Ian Dunlop MBE John Wells-Thorpe OBE Honorary Secretary John Small FRIBA FRSA Honorary Treasurer Stephen Neiman Committee Secretary Dinah Staples Membership Secretary Jackie FitzGerald Executive Committee Nick Tyson David Beevers Nigel Robinson Robert Nemeth Selma Montford Duncan McNeill Eileen Hollingdale Dr. Elizabeth Darling Rupert Radcliffe-Genge Elaine Evans (Hove Civic Society representative) Registered Charity No. 210194 The Regency Society of Brighton and Hove ANNUAL REPORT 2005 his annual report marks the conclusion of my six years as Chairman of the Regency Society. It has been a privilege to serve this remarkable institution in Tthis time - a period which has encompassed quite extraordinary change, not least in the newly merged boroughs of Brighton and Hove being declared as a city. Such municipal status has been emblematic of an energy for development, on many fronts, that ushers in myriad schemes for building and conversion which the Regency Society and its officers have a distinct role to play in accessing the architectural merits and sensitivities of such change and growth. These are exciting, if challenging, times. The built environment of Brighton and Hove has emerged in phases of distinct and notable styles - from our eponymous Regency, through Victorian and Edwardian epochs, significant elements of 20th century modernism, the bold and sweeping educational expansion of the 1960s, which brought us the University of Sussex, and now a much heightened general interest in new architecture, and a revived celebratory status for a range of individual architects and their practices. -

Heritage-Statement

Document Information Cover Sheet ASITE DOCUMENT REFERENCE: WSP-EV-SW-RP-0088 DOCUMENT TITLE: Environmental Statement Chapter 6 ‘Cultural Heritage’: Final version submitted for planning REVISION: F01 PUBLISHED BY: Jessamy Funnell – WSP on behalf of PMT PUBLISHED DATE: 03/10/2011 OUTLINE DESCRIPTION/COMMENTS ON CONTENT: Uploaded by WSP on behalf of PMT. Environmental Statement Chapter 6 ‘Cultural Heritage’ ES Chapter: Final version, submitted to BHCC on 23rd September as part of the planning application. This document supersedes: PMT-EV-SW-RP-0001 Chapter 6 ES - Cultural Heritage WSP-EV-SW-RP-0073 ES Chapter 6: Cultural Heritage - Appendices Chapter 6 BSUH September 2011 6 Cultural Heritage 6.A INTRODUCTION 6.1 This chapter assesses the impact of the Proposed Development on heritage assets within the Site itself together with five Conservation Areas (CA) nearby to the Site. 6.2 The assessment presented in this chapter is based on the Proposed Development as described in Chapter 3 of this ES, and shown in Figures 3.10 to 3.17. 6.3 This chapter (and its associated figures and appendices) is not intended to be read as a standalone assessment and reference should be made to the Front End of this ES (Chapters 1 – 4), as well as Chapter 21 ‘Cumulative Effects’. 6.B LEGISLATION, POLICY AND GUIDANCE Legislative Framework 6.4 This section provides a summary of the main planning policies on which the assessment of the likely effects of the Proposed Development on cultural heritage has been made, paying particular attention to policies on design, conservation, landscape and the historic environment. -

BHOD Programme 2016

Brighton & Hove Open Door 2016 8 – 11 September PROGRAMME 90 FREE EVENTS celebrating the City’s heritage Contents General Category Open Door and Pre-booked events Page 3-4 My House My Street Open Door and Pre-booked events Page 4-5 Here in the Past Open Door and Pre-booked events Page 5 Walks Open Door and Pre-booked events Page 5-8 Religious Spaces Open Door and Pre-booked events Page 8-11 Fashionable Houses Open Door and Pre-booked events Page 11-12 Silhouette History Open Door and Pre-booked events Page 12 Industrial & Commercial Open Door and Pre-booked events Page 12-14 Education Open Door and Pre-booked events Page 14-15 Garden & Nature Open Door and Pre-booked events Page 15 Art & Literature Open Door and Pre-booked events Page 15 Theatre & Cinema Open Door and Pre-booked events Page 15-16 Archaeology Open Door and Pre-booked events Page 16 Architecture Open Door and Pre-booked events Page 17 About the Organisers Brighton & Hove Open Door is organised annually by staff and volunteers at The Regency Town House in Brunswick Square, Hove. The Town House is a grade 1 Listed terraced home of the mid-1820s, developed as a heritage centre with a focus on the city’s rich architectural legacy. Work at the Town House is supported by The Brunswick Town Charitable Trust, registered UK charity number 1012216. About the Event Brighton & Hove Open Door is always staged during the second week of September, as a part of the national Heritage Open Days (HODs) – a once-a-year chance to discover architectural treasures and enjoy tours and activities about local history and culture. -

Download Report

Results of continuous monitoring, 2015 Sussex Air Pollution Monitoring Network Annual Report, 2015 September 2016 Hima Chouhan Environmental Research Group King’s College London SAQMN 1 Annual Report, 2015 Results of continuous monitoring, 2015 Environmental Research Group Kings College London Franklin-Wilkins Building 150 Stamford Street LONDON SE1 9NH Telephone: +44 (0) 20 7848 4044 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7848 4045 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.erg.kcl.ac.uk SAQMN 2 Annual Report, 2015 Results of continuous monitoring, 2015 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................. 4 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 5 CHAPTER 1: Results of Continuous Monitoring, 2015 ............................... 7 Network performance ............................................................................................................. 7 A statistical overview of 2015 ................................................................................................. 9 Significant episodes occurring during 2015 ......................................................................... 15 2015 in Comparison with the Air Quality Strategy (AQS) Objectives .................................. 17 Indicators of Sustainable Development ............................................................................... 20 CHAPTER 2: Trends in Pollution Levels, 2001 – 2015 .............................. 23 How the Charts Work .......................................................................................................... -

BNMS Brighon Programme

32ND Annual Meeting BRITISH NUCLEAR MEDICINE SOCIETY 31st March - 2nd April 2004 BRIGHTON CONFERENCE CENTRE PROGRAMME www.bnms.org.uk MAXIMUM 14 CPD/CME CREDITS CONTENTS BRITISH NUCLEAR MEDICINE SOCIETY 2 COUNCIL 2 SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE 2 CONFERENCE ORGANISATION 2 SOCIETY MEMBERSHIP 2 SUBSCRIPTION RATES 2 CONFERENCE REGISTRATION 2 GENERAL INFORMATION 3 PRE-REGISTRATION 3 REGISTRATION 3 HOTEL ACCOMMODATION 3 CATERING 3 COMMERCIAL EXHIBITION - MAIN HALL 3 EMERGENCY CONTACT DETAILS 3 SOCIAL EVENTS 4 GENERAL PROGRAMME 5 DAY 1 - WEDNESDAY 31ST MARCH 2004 5 DAY 2 - THURSDAY 1ST APRIL 2004 6 DAY 3 - FRIDAY 2ND APRIL 2004 7 DETAILED PROGRAMME 8 DAY 1 - WEDNESDAY 31ST MARCH 2004 8 - 9 DAY 2 - THURSDAY 1ST APRIL 2004 10 - 11 DAY 3 - FRIDAY 2ND APRIL 2004 12 - 13 POSTER PRESENTATIONS 14 FINDING YOUR WAY TO BRIGHTON 16 BRIGHTON MAP 17 EXHIBITING COMPANIES 2004 18-19 PLAN OF MAIN HALL 20 BNMS MEMBERSHIP APPLICATION FORM 23 METHODS OF MEMBERSHIP PAYMENT 24 1 BRITISH NUCLEAR MEDICINE SOCIETY 32nd Annual Meeting BRITISH NUCLEAR MEDICINE SOCIETY SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE 2003/04 COUNCIL MEMBERS Prof M Frier President Dr M Prescott Dr A Al-Nahhas President-Elect Dr A Hilson Dr C Anagnostopoulos Hon Secretary Dr W Tindale Dr B Ellis Hon. Treasurer Dr S Hesslewood Dr R Ganatra Dr A Al-Nahhas Prof R Lawson BNCS President Dr A Kelion Mrs V Parkin Mr S Chandler Dr M Prescott Dr M Darby Dr W Tindale Dr J Dutton Dr S Vinjamuri Radiopharmacy Chair Dr B Ellis IPEM Representative - Mr P Hinton Dr R Ganatra Prof R Lawson Technologists Chair Mrs V Parkin Dr P Ryan Dr S Vinjamuri CONFERENCE ORGANISATION President Dr M Prescott Exhibition Organiser Mrs S Hatchard Honorary Secretary Dr W Tindale Poster Session Organiser Dr R Ganatra PA to Honorary Secretary Mrs N Cavell Judging Chairman Dr G Vivian Conference Secretary Mrs S Hatchard Marketing Dr A Tweddel SOCIETY MEMBERSHIP Membership of the Society is open to those who have a substantial interest and involvement in the development and provision of Nuclear Medicine services. -

East Cliff Conservation Area Study and Enhancement Plan

EAST CLIFF CONSERVATION AREA STUDY AND ENHANCEMENT PLAN Director Of Environment September 2002 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 East Cliff was designated as a conservation area in February 1973 in recognition of it being an area of special architectural and historic interest, due to its clear association with the growth of Brighton as a Regency and Victorian seaside resort. The conservation area was confirmed as “outstanding” by the Secretary of State for the Environment in January 1974. It was then extended to the north in January 1977, June 1989 and June 1991. East Cliff covers an area of approximately 60 hectares and contains 589 statutory listed buildings plus 86 buildings on the local list. 1.2 This document contains an appraisal of the special architectural and historic interest of the conservation area, which is based upon a summary of the history and development of the area. It then goes on to recommend extensions to the boundary of the conservation area, under the terms of Section 69(2) of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. Part five of the Study identifies buildings of local interest and buildings and sites which detract from the area. The Enhancement Plan aspect of this document has been prepared under Section 71 of the above-mentioned Act and sets out action that should be taken in order to preserve and enhance the special character and appearance of the area. 1.3 No estimate exists of the population of East Cliff as it covers parts of two separate wards and neighbourhoods. However, it has been estimated by the council that there are in the region of 10,500 households in the conservation area. -

Industrial Archaeology Tour Notes for Sussex

Association for Industrial Archaeology Annual Conference Brighton 2015 Industrial Archaeology Tour Notes for Sussex Compiled and Edited by Robert Taylor Sussex Industrial Archaeology Society Welcome to Sussex We trust you will enjoy the tours which extend across the county from Goodwood in the west to Hastings in the east and north to Gatwick. We have tried to fit as many visits as possible, but as a consequence the timings for all the tours are tight, so please ensure you return to the coach no later than the time stated by the tour leader and note any instructions they or the driver may give. Most of the places that we visit are either public open spaces or sites, buildings, or structures that are open to the public on a regular basis. Please be aware that all tour members have a responsibility to conduct themselves in a safe and appropriate manner, so do take care when boarding or alighting from vehicles, particularly if crossing in front of or behind the vehicle where one’s view may be obstructed. Similarly care should be exercised when ascending or descending steps or steep slopes and paths that may additionally be slippery when wet. Where we are visiting a site that is not usually open to the public, further instructions will be provided by the Tour Guide when we get to the site. Our best wishes for enjoyable time Committee of the Sussex Industrial Archaeology Society To assist with identifying the sites while on the bus tours the Field Guide / Gazetteer booklet references are included in the notes for each tour. -

Patcham Conservation Area Appraisal

Patcham Conservation Area Appraisal Designated: 1970 Extended: 1972, 1992 and 2010 Area: 16.21 Hectares 40.05 Acres Article 4 Direction: Proposed Character Statement adopted: 2010 Introduction Location and Setting The historic village of Patcham is located 5.5 km north of Brighton's seafront. It comprises a historic downland village, set beside the A23 and now on the northern edge of the city. The conservation area stretches along Old London Road between Ladies Mile Road to the south and the Black Lion Hotel, to Patcham Place and Coney Wood to the west and northwest, and along Church Hill to the junction with Vale Avenue to the north. Patcham is located in a wide north-south aligned valley. This topography enabled easy passage inland from Brighton, leading in due course to the formation of the London to Brighton road. This strategic location had a major impact on the development of the village, both in terms of its original formation as a hub for the local agricultural economy, and later in catering for trade along the route. The village originally developed around one of several springs that form the source of the Wellsbourne stream. The stream now runs underground. However prolonged heavy rain can cause the stream to surface and flood the area. This occurred most recently in 2000. Amongst its heritage assets, the area contains 33 listed buildings, 1 locally listed building, a scheduled ancient monument and an archaeological notification area (see Existing Designations Graphic). It was designated as a conservation area in September 1970, and extended in September 1972, September 1992 and December 2010. -

27Th Sussex Edition = September 2011

Post your form, or enquiries with SAE, to Dinnages, Unit 11, Hove, BN3 5RA Established & successful trading since February 1989. Historic Transport & Local Photographs A Unique library of photographs from original material Prints available as album 6x4 views & mounted 9x6 27th Sussex Edition = September 2011 Stockist of current bus and railway booklets from; Maidstone & District and East Kent Bus Club Southdown = 8, NBC = 11, BH&D = 4, The Omnibus Society, PHRS Book series Eastbourne = 2, Brighton Corporation = 11 Peter A Harding, Branch Line Railway Series Another round of 8 colour slides from Jack Turley, with the usual 28 B&W Buggleskelly Railway books this month, again from Jack Turley, Jim Jones, Ernest Charman, & Gordon Gangloff. Each issue aims to use a variety of our photographers, Always a selection of used & obsolete transport books the spread of content & of this historic period too between 1937 & 1985. Historic & Contemporary Transport Films on DVD We are still looking for your feedback on the online survey, on what you would like to see, & in other editions. Speaking of which, we are to Check out our Online store or auction sales. release our first KENT EDITION on the 1st October at the Maidstone Toy Postal Sales & enquiries welcome, or find us at an event. Fair, with coverage of Maidstone & District, Maidstone Corporation, East An established family concern, trading over 22 years. Kent, those operators involved like the Ex Hastings Trolleybuses, along with Kent independents, all catering for the same historic period between The Dinnages Library has been created from original negatives 1937 & mid eighties, & covering from the trolleybuses. -

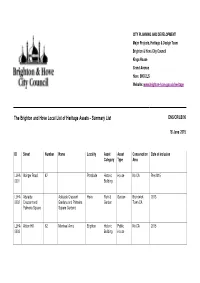

The Brighton and Hove Local List of Heritage Assets – Summary List ENS/CR/LB/06

CITY PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT Major Projects, Heritage & Design Team Brighton & Hove City Council Kings House Grand Avenue Hove BN3 2LS Website: www.brighton-hove.gov.uk/heritage The Brighton and Hove Local List of Heritage Assets – Summary List ENS/CR/LB/06 18 June 2015 ID Street Number Name Locality Asset Asset Conservation Date of inclusion Category Type Area LLHA Abinger Road 87 Portslade Historic House No CA Pre-2015 0001 Building LLHA Adelaide Adelaide Crescent Hove Park & Garden Brunswick 2015 0002 Crescent and Gardens and Palmeira Garden Town CA Palmeira Square Square Gardens LLHA Albion Hill 62 Montreal Arms Brighton Historic Public No CA 2015 0003 Building House LLHA Arcade Buildings 1-17 Imperial Arcade Brighton Historic Shop, No CA Pre-2015 0242 and 203-211 Building arcade Western Road LLHA Bath Street Petrol Pumps at 19A Brighton Historic Transport - West Hill CA 2015 0004 Building Petrol Pumps LLHA Bedford Place 3 Brighton Historic House Regency Pre-2015 0005 Building Square CA LLHA Boundary Road 29, 30 Hove Historic Houses, No CA Pre-2015 0006 Building now office, shop and dwelling LLHA Braybon Avenue Fountain Centre Brighton Historic Place of No CA 2015 0007 Building Worship - Anglican LLHA Bristol Gardens 12 The Estate of the First Brighton Historic Estate Within and 2015 0008 Marquis of Bristol: 12 Building buildings outside Kemp Bristol Gardens; 1-11 and walls Town CA (odd) Church Place; Walls to Badger's Tennis Courts; Walls to former Bristol Nurseries LLHA Brunswick Square Brunswick Square Hove Park & Garden Brunswick