^^Statement by Sheldon Hackney Nominee for the Position Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

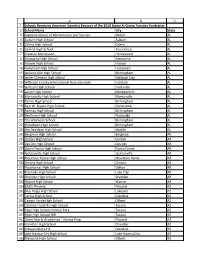

Schools Receiving American Scientist Because of the 2019 Sigma Xi

A B C 1 Schools Receiving American Scientist Because of the 2019 Sigma Xi Giving Tuesday Fundraiser 2 School Name City State 3 Alabama School of Mathematics and Science Mobile AL 4 Auburn High School Auburn AL 5 Calera High School Calera AL 6 Central High School Tuscaloosa AL 7 Creative Montessori Homewood AL 8 Enterprise High School Enterprise AL 9 Hoover High School Hoover AL 10 Hueytown High School Hueytown AL 11 Jackson-Olin High School Birmingham AL 12 James Clemens High School Madison City AL 13 Jefferson County International Bacculaureate Irondale AL 14 Jemison High School Huntsville AL 15 Lanier High School Montgomery AL 16 Montevallo High School Montevallo AL 17 Parker High School Birmingham AL 18 Paul W. Bryant High School Cottondale AL 19 Ramsay High School Birmingham AL 20 Reeltown High School Notasulga AL 21 The Altamont School Birmingham AL 22 Woodlawn High School Birmingham AL 23 Wp Davidson High School Mobile AL 24 Bergman High School Bergman AR 25 Clinton High School Clinton AR 26 Des Arc High School Des Arc AR 27 Green Forest High School Green Forest AR 28 Jacksonville High School Jacksonville AR 29 Mountain Home High School Mountain Home AR 30 Omaha High School Omaha AR 31 Pocahontas High School Dalton AR 32 Riverside High School Lake City AR 33 Sheridan High School Sheridan AR 34 Wynne High School Wynne AR 35 BASIS Phoenix Phoenix AZ 36 Blue Ridge High School Lakeside AZ 37 Cactus High School Glendale AZ 38 Campo Verde High School Gilbert AZ 39 Catalina Foothills High School Tucson AZ 40 Edge High School Himmel Park Tucson AZ 41 Edge High School NW Tucson AZ 42 Great Hearts Academies - Veritas Prep Phoenix AZ 43 Hamilton High School Chandler AZ 44 Independence HS Glendale AZ 45 Lake Havasu City High School Lake Havasu City AZ 46 Mesquite High School Gilbert AZ A B C 47 Show Low High School Show Low AZ 48 Veritas Preparatory Academy Phoenix AZ 49 American Heritage School Plantation FL 50 Apopka High School Apopka FL 51 Booker T. -

High Schools in Alabama Within a 250 Mile Radius of Middle Tennessee State University

High Schools in Alabama within a 250 mile radius of Middle Tennessee State University CEEB High School Name City Zip Code CEEB High School Name City Zip Code 010395 A H Parker High School Birmingham 35204 012560 B B Comer Memorial School Sylacauga 35150 012001 Abundant Life School Northport 35476 012051 Ballard Christian School Auburn 36830 012751 Acts Academy Valley 36854 012050 Beauregard High School Opelika 36804 010010 Addison High School Addison 35540 012343 Belgreen High School Russellville 35653 010017 Akron High School Akron 35441 010035 Benjamin Russell High School Alexander City 35010 011869 Alabama Christian Academy Montgomery 36109 010300 Berry High School Berry 35546 012579 Alabama School For The Blind Talladega 35161 010306 Bessemer Academy Bessemer 35022 012581 Alabama School For The Deaf Talladega 35161 010784 Beth Haven Christian Academy Crossville 35962 010326 Alabama School Of Fine Arts Birmingham 35203 011389 Bethel Baptist School Hartselle 35640 010418 Alabama Youth Ser Chlkvlle Cam Birmingham 35220 012428 Bethel Church School Selma 36701 012510 Albert P Brewer High School Somerville 35670 011503 Bethlehem Baptist Church Sch Hazel Green 35750 010025 Albertville High School Albertville 35950 010445 Beulah High School Valley 36854 010055 Alexandria High School Alexandria 36250 010630 Bibb County High School Centreville 35042 010060 Aliceville High School Aliceville 35442 012114 Bible Methodist Christian Sch Pell City 35125 012625 Amelia L Johnson High School Thomaston 36783 012204 Bible Missionary Academy Pleasant 35127 -

Upcoming Events May / 2015

Page 3..…………………...…..………Spotlight on Youth Page 4…………….…………..Take Our Youth to Work Page 8…………………………….…..……Tech Education MAY / 2015 William A. Bell, Sr., Mayor Cedric D. Sparks, Sr., Executive Director 1608 7TH AVENUE N | BIRMINGHAM, AL 35203 | PH: (205) 320-0879 | FAX: (205) 297-8139 | www.bhamyouthfirst.org UPCOMING EVENTS May 16, 2015 May 16, 2015 May 16, 2015 May 15-31, 2015 May 20—24, 2015 COLLEGE FAIR SMART ART YOUTH DO DAH DAY Red Mountain Theatre DISNEY’S FROZEN ON 10:00am 2:00pm ARTS FESTIVAL 11:00am—5:00pm Company presents ICE Willow Wood Recreation 11:00am—3:00pm Caldwell Park THE WIZ 7:00pm—9:00pm Center Boutwell Auditorium RMTC BJCC For more info: For more info: For more info: www.dodahday.org For more info: For more info: (205) 591-1798 (205) 320-0879 (205) 324-2424 (800) 745-3000 Srihari Prahadeeswaran Hoover High School D1 Sports Training Kendrick McKinney A.H. Parker High School Birmingham tuned in on th Alabama Adventure April 16 to watch the 2015 Kids & Jobs Craig Taylor Draft. With the help of 2015 Draft Participants Ramsay High School the City of Birmingham ReVamp, LLC Mayor’s Office Division of Youth teamwork and professional skills. Services’ (DYS) staff and FOX6 six After a series of interviews and Hannah Woods participants competed to win paid teamwork challenges, the top six Oak Grove High School internships with companies looking students were selected by area to hire Birmingham’s best and Smoke Law, LLC companies: brightest young people. Miaya Webster Josselyn Cruz Selected from the top students Alabama School of Fine Arts G.W. -

UNIVERSITY of PENNSYLVANIA Two Hundred Thirty-Fifth Commencement for the Conferring of Degrees

UNIVERSITY of PENNSYLVANIA Two Hundred Thirty-Fifth Commencement for the Conferring of Degrees FRANKLIN FIELD Tuesday, May 21, 1991 SEATING DIAGRAM Guests will find this diagram helpful in locating the approximate seating of the degree candidates. The seating roughly corresponds to the order by school in which the candidates for degrees are presented, beginning at top left with the College of Arts and Sciences. The actual sequence is shown in the Contents on the opposite page under Degrees in Course. Reference to the paragraph on page seven describing the colors of the candidates' hoods according to their fields of study may further assist guests in placing the locations of the various schools. STAGE Graduate Faculty Faculty Faculties Engineering Nursing Medicin College College Wharton Dentaline Arts Dental Medicine Veterinary Medicine Wharton Education Graduate Social Work Annenberg Contents Page Seating Diagram of the Graduating Students . 2 The Commencement Ceremony .. 4 Commencement Notes .. 6 Degrees in Course . 8 The College of Arts and Sciences .. 8 The College of General Studies . 17 The School of Engineering and Applied Science .. 18 The Wharton School .. 26 The Wharton Evening School .. 30 The Wharton Graduate Division .. 32 The School of Nursing .. 37 The School of Medicine .. 39 The Law School .. 40 The Graduate School of Fine Arts .. 42 The School of Dental Medicine .. 45 The School of Veterinary Medicine .. 46 The Graduate School of Education .. 47 The School of Social Work .. 49 The Annenberg School for Communication .. 50 The Graduate Faculties .. 51 Certificates .. 57 General Honors Program .. 57 Advanced Dental Education .. 57 Education .. 58 Fine Arts .. 58 Commissions . -

SHAKERS a Rich Past Revisited EDITOR's NOTE

THE SHAKERS A Rich Past Revisited EDITOR'S NOTE The Future of the Book t h e SHAKERS The usually staid Ralph Waldo Emerson had a mischievous moment A Rich Past Revisited when it came to books. "A man's library/' he said, "is a sort of harem." Well, without taking the analogy too far, the nature of the harem is changing. Some of the inhabitants are breaking away. In this issue of Humanities we look at the future of the book. Endow ment Chairman Sheldon Hackney talks with John Y. Cole, director of the Center for the Book at the Library of Congress, about the sixteen- year effort there to preserve a place for the book in a world of tapes and Blacksmith's Shop, Hancock Shaker Village, CD-ROMs. "I do think that many kinds of books will disappear," Cole Massachusetts. —Photo by Ken Bums tells us. "And as the pace of technology accelerates, books and print culture will probably play an even more diminished overall role in our society." Whether that is a matter for concern is explored in subsequent pages: Charles Henry of Vassar examines what happens when elec Humanities tronic tools are applied to the traditional academic disciplines, and A bimonthly review published by the raises questions about what it may mean to definitions of undergrad National Endowment for the Humanities. uate and graduate education when doctoral candidates can find in an afternoon's search on a database what it might have taken earlier Chairman: Sheldon Hackney scholars months or years to sift through. And finally, the role played by books in the shaping of our democracy is the subject of a multi Editor: Mary Lou Beatty volume work in progress called A History of the Book in America; it is a Assistant Editors: Constance Burr companion to works published or underway in France, Germany, Great Susan Q. -

African American History and Radical Historiography

Vol. 10, Nos. 1 and 2 1997 Nature, Society, and Thought (sent to press June 18, 1998) Special Issue African American History and Radical Historiography Essays in Honor of Herbert Aptheker Edited by Herbert Shapiro African American History and Radical Historiography Essays in Honor of Herbert Aptheker Edited by Herbert Shapiro MEP Publications Minneapolis MEP Publications University of Minnesota, Physics Building 116 Church Street S.E. Minneapolis, MN 55455-0112 Copyright © 1998 by Marxist Educational Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging In Publication Data African American history and radical historiography : essays in honor of Herbert Aptheker / edited by Herbert Shapiro, 1929 p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) ISBN 0-930656-72-5 1. Afro-Americans Historiography. 2. Marxian historiography– –United States. 3. Afro-Americans Intellectual life. 4. Aptheker, Herbert, 1915 . I. Shapiro, Herbert, 1929 . E184.65.A38 1998 98-26944 973'.0496073'0072 dc21 CIP Vol. 10, Nos. 1 and 2 1997 Special Issue honoring the work of Herbert Aptheker AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY AND RADICAL HISTORIOGRAPHY Edited by Herbert Shapiro Part I Impact of Aptheker’s Historical Writings Essays by Mark Solomon; Julie Kailin; Sterling Stuckey; Eric Foner, Jesse Lemisch, Manning Marable; Benjamin P. Bowser; and Lloyd L. Brown Part II Aptheker’s Career and Personal Influence Essays by Staughton Lynd, Mindy Thompson Fullilove, Catherine Clinton, and Rosalyn Terborg-Penn Part III History in the Radical Tradition of Herbert Aptheker Gary Y. Okihiro on colonialism and Puerto Rican and Filipino migrant labor Barbara Bush on Anglo-Saxon representation of Afro- Cuban identity, 1850–1950 Otto H. -

ED 326 509 TITLE INSTITUTION PUB DATE AVAILABLE from PUB TYPE EDRS PRICE DESCR:PTORS IDENTIFIERS LBSTRACT the Carnegie Foundatio

150C1114EIT ED 326 509 SP 032 742 TITLE The Carnegie Foundationfor the Advancement of Teaching. Eighi TourthAnnual Report for the Year Ended June 30, 1989. INSTITUTION Carnegie Foundation forthe Advancement of Teaching, Princeton, NJ. PUB DATE 89 NOTE 50p. AVAILABLE FROM The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, 5 Ivy Lane, Princeton, NJ 08540. PUB TYPE Reports - General (140) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCR:PTORS *Educational Improvement; Educationally Disadvantaged; Elementary Secondary Education; *Equal Education; *Excellence in Education; Financial Support; Philanthropic Foundations; *Professional Recognition; School Based Management; *School Restructuring; State Standards IDENTIFIERS *National Priorities LBSTRACT This annual report of the Carnegie Foundation sets forth the goals the foundation has established for the improvementof education: (1) an urgent call to national action in school reform; (2) a commitment to the disadvantaged; (3) a crusaue to strengthen teaching; (4) state standards, with leadership at the local school; (5) a quality curriculum; and (6) an effective way to monitor results. The report of the,foundation's treasurer provides comprehensive information on the income and xpenditures for the year. The Carnegie philanthropies are briefly described.(JD) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can De made from the original document. gggg************** ************ g. - - , , V$'4, ',.-4 , r; The Carnegie F,undation for the Advancement ofTeaching was founded by Andrew Carnegie in 1905 and chartered by Congress in 1906. Long concerned with pensions and pension systems for college and university teachers, the Foundation has also sponsored extensive research on education. As an independent policy center, it now conducts studies devoted to the strengthening of American education at all levels. -

Tlu Lictutstilnatttatt ^ W T? Fmmrlrrl 1885

tlu lictutstilnatttatt ^ W T? fmmrlrrl 1885 ■•■''' lily . , , Vol. \CIX.\o.6l I'llll AHHPHIA.July I. 1983 Minority admissions fall in larger Class of 1987 Officials laud geographic diversity B> I -At KfN ( (II I MAN the) are pleased with the results ol a \ target class ol 1987 contains dtive 10 make the student bod) more liginificantl) fewei minority geographicall) diverse, citing a students but the group is the Univer- decrease in the numbet ol students sity's most geographicall) diverse from Ihe Northeast in the c lass ol class ever. 198". A- ol late May, 239 minority ot the 4191 students who were at -indents had indicated the) will cepted to the new freshman class. matriculate at the i niversit) in the 2178 indicated b) late \lav that the) fall as members ol the new will matricualte, a 4" percent yield. freshman class, a drop ol almost 5 Provost l hi'ina- Ehrlich said that percent from last year's figure of increasing geographic diversit) i- 251. one ol the I Diversity's top goal-. Acceptances from t hicano and "I'm ver) pleased particularl) in Asian students increased this vear, terms of following out goal of DP Steven Siege bin the number of Hacks and geographic diversit) while maintain- I xuhcranl tans tearing down the franklin Held goalpost! after IRC Quakers" 23-2 victor) over Harvard latino- dropped sharply. Hie new ing academic quality," he said. "The freshman class will have 113 black indicator- look veiv good." -indents, compared wilh 133 last Stetson -.ml the size ol the i lass veat a decline ol almost 16 per ol 1987 will not be finalized until cent tin- month, when adjustments are Champions But Vlmissions Dean I ee Stetson made I'm students who decide 10 Bl LEE STETSON lend oilier schools Stetson said he said the Financial MA Office i- 'Reflection oj the econom\' working to provide assistance winch plan- "limited use" ol the waiting will permit more minority students list to fill vacancies caused by an Iwentv two percent ol the class Quakers capture Ivy football crown to matriculate. -

Remarks of Sheldon Hackney Chairman, National Endowment For

Remarks of Sheldon Hackney Chairman, National Endowment for the Humanities At the Annual Convention of the American Historical Association Chicago, Illinois January 7, 1995 I come to you today still somewhat dazed &y the events \ of November 8 and their aftermath, which are plkying themselves out in the hyperbaric chamber that is Washington. Many meanings, both emergent and contingent, are contained in the current political situation and the public mood it reflects, and my interpretation is no better than the next lay person's attempt to make sense of this history-in-the- making. One theme is clear, however, and it is pertinent to our current purpose. In the primary conversation of American history between liberty and equality, liberty now has the floor. I recall being intrigued by something that the poet, Donald Hall, said some time ago in his televised interview with Bill Moyers. He recited a little poem and then explained it, only to be told by Moyers that the poem had an entirely different meaning to him. Hall confessed I appreciatively that he had never thought of the poem in the way Moyers interpreted it, and then he said, "A poem ■ j \ frequently has at the same time the meaning the^poet intended and the opposite meaning as well." I was reminded immediately of Sigmund Freud's crack that neurotic symptoms are both punishment and reward, and I kept thinking about the implications of Hall's profound observation. It soon occurred to me that nature seems to be filled with examples of binary opposites that complete each other: Male-Female North and South poles of magnets, and of earth The genetic code arrayed along strands of the double 2 helix So it is with culture, especially American culture. -

The Literal and Figurative Boundaries Between Penn Students and West Philadelphia Yasmin Radjy University of Pennsylvania

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarlyCommons@Penn University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Senior Seminar Papers Urban Studies Program 2007 The Literal and Figurative Boundaries Between Penn Students and West Philadelphia Yasmin Radjy University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.upenn.edu/senior_seminar Part of the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Radjy, Yasmin, "The Literal and Figurative Boundaries Between Penn Students and West Philadelphia" (2007). Senior Seminar Papers. 6. http://repository.upenn.edu/senior_seminar/6 Suggested Citation: Radjy, Yasmin. "The Literal and Figurative Boundaries Between Penn Students and West Philadelphia." University of Pennsylvania, Urban Studies Program. 2007. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/senior_seminar/6 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Literal and Figurative Boundaries Between Penn Students and West Philadelphia Abstract In this paper, I discuss the literal and figurative boundaries that stand between Penn students and West Philadelphia. I begin by discussing the theory behind walls and boundaries, then applying this theory to the urban environment and then to town-gown relations, finally applying these theories to the case of Penn and West Philadelphia. In order to fully understand the walls that stand between campus and community, I look at the history of town-gown relations—both nationally and at Penn, dividing up the history into three phases: first, the nineteenth century, during which the “Ivory Tower” relationship of division first began; next, the post-World War II era, when race and class issues became relevant in campus-community relations, as relations became increasingly divided and turbulent; and finally, the post-cold war era that has lasted until the present day, during which the importance of knocking down barriers between institutions and communities has been emphasized. -

UM High School Honor Band Accepted Students Student's Name

UM High School Honor Band Accepted Students Student's Name Instrument Grade School Katie Cheslock Alto Clarinet 11 Chelsea High School Anna Bell Alto Saxophone 9 West Blockton High School Arianna Adams Alto Saxophone 9 Fultondale High School Avery Bertschinger Alto Saxophone 9 Montevallo High School Brianna Lodge Alto Saxophone 9 Fairview High School Christopher Watts Alto Saxophone 11 Jefferson Davis High School Daniel Spires Alto Saxophone 9 Thompson High School Dany Pedraza Alto Saxophone 10 White Plains High School David Boykin Alto Saxophone 11 Jefferson Davis High School Eddie Anthony Alto Saxophone 12 Montevallo High School Emma Johnson Alto Saxophone 9 Helena High School Emma Mansour Alto Saxophone 11 Cullman High School Faith Sutton Alto Saxophone 9 Carbon Hill High School Gabriela Guiterrez Alto Saxophone 9 White Plains High School Galena Townsend Alto Saxophone 10 Munford High School Gavin Terrell Alto Saxophone 11 Weaver High School Iasiah Adams Alto Saxophone 12 Choctaw County High School Jackson Stapleton Alto Saxophone 10 East Limestone High School Jade Capps Alto Saxophone 9 Curry High School Janie Gray Alto Saxophone 9 Montevallo High School Jerry Wilkins Alto Saxophone 9 Winterboro High School Jonah Burson Alto Saxophone 11 Weaver High School Josh Wesson Alto Saxophone 10 McAdory High School Justin Singleton Alto Saxophone 10 West Blockton High School Mikailie Caulder Alto Saxophone 9 Weaver High School Natalie Davis Alto Saxophone 10 Cold Springs High School Nich Honeycutt Alto Saxophone 10 Brookwood High School Olivia -

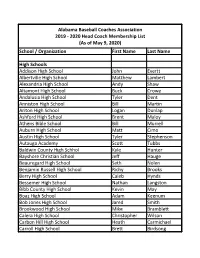

ALABCA Head Coach (WEB SITE) Member List at of May 9, 2020.Xltx

Alabama Baseball Coaches Association 2019 - 2020 Head Coach Membership List (As of May 9, 2020) School / Organization First Name Last Name High Schools Addison High School John Evertt Albertville High School Matthew Lambert Alexandria High School Andy Shaw Altamont High School Buck Crowe Andalusia High School Tyler Dent Anniston High School Bill Martin Ariton High School Logan Dunlap Ashford High School Brent Maloy Athens Bible School Bill Murrell Auburn High School Matt Cimo Austin High School Tyler Stephenson Autauga Academy Scott Tubbs Baldwin County High Schhol Kyle Hunter Bayshore Christian School Jeff Hauge Beauregard High School Seth Nolen Benjamin Russell High School Richy Brooks Berry High School Caleb Hynds Bessemer High School Nathan Langston Bibb County High School Kevin May Boaz High School Adam Keenum Bob Jones High School Jared Smith Brookwood High School Mike Bramblett Calera High School Christopher Wilson Carbon Hill High School Heath Carmichael Carroll High School Brett Birdsong Page 2 - School / Organization First Name Last Name Center Point High School Davion Singleton Central High School AJ Kehoe Chelsea High School Michael Stallings Childersburg High School Josh Podoris Chilton County High School Ryan Ellison Choctaw County High School Gary Banks Citronelle High School JD Phillips Clements High School Brody Gibson Collinsville High School Shane Stewart Cordova High School Lytle Howell Cullman High School Brent Patterson Curry High School Jeffrey Dean Dadeville High School Curtis Sharpe Dale County High School Patrick