The Onomastic Sam Shepard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read Aeschylus The Persians (472 BC) McCullers A Member of the Wedding The Orestia (458 BC) (1946) Prometheus Bound (456 BC) Miller Death of a Salesman (1949) Sophocles Antigone (442 BC) The Crucible (1953) Oedipus Rex (426 BC) A View From the Bridge (1955) Oedipus at Colonus (406 BC) The Price (1968) Euripdes Medea (431 BC) Ionesco The Bald Soprano (1950) Electra (417 BC) Rhinoceros (1960) The Trojan Women (415 BC) Inge Picnic (1953) The Bacchae (408 BC) Bus Stop (1955) Aristophanes The Birds (414 BC) Beckett Waiting for Godot (1953) Lysistrata (412 BC) Endgame (1957) The Frogs (405 BC) Osborne Look Back in Anger (1956) Plautus The Twin Menaechmi (195 BC) Frings Look Homeward Angel (1957) Terence The Brothers (160 BC) Pinter The Birthday Party (1958) Anonymous The Wakefield Creation The Homecoming (1965) (1350-1450) Hansberry A Raisin in the Sun (1959) Anonymous The Second Shepherd’s Play Weiss Marat/Sade (1959) (1350- 1450) Albee Zoo Story (1960 ) Anonymous Everyman (1500) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Machiavelli The Mandrake (1520) (1962) Udall Ralph Roister Doister Three Tall Women (1994) (1550-1553) Bolt A Man for All Seasons (1960) Stevenson Gammer Gurton’s Needle Orton What the Butler Saw (1969) (1552-1563) Marcus The Killing of Sister George Kyd The Spanish Tragedy (1586) (1965) Shakespeare Entire Collection of Plays Simon The Odd Couple (1965) Marlowe Dr. Faustus (1588) Brighton Beach Memoirs (1984 Jonson Volpone (1606) Biloxi Blues (1985) The Alchemist (1610) Broadway Bound (1986) -

Sam Shepard One Acts: War in Heaven (Angel’S Monologue), the Curse of the Raven’S Black Feather, Hail from Nowhere, Just Space Rhythm

Sam Shepard One Acts: War in Heaven (Angel’s Monologue), The Curse of the Raven’s Black Feather, Hail from Nowhere, Just Space Rhythm Resource Guide for Teachers Created by: Lauren Bloom Hanover, Director of Education 1 Table of Contents About Profile Theatre 3 How to Use This Resource Guide 4 The Artists 5 Lesson 1: Who is Sam Shepard? Classroom Activities: 1) Biography and Context 6 2) Shepard in His Own Words 6 3) Shepard Adjectives 7 Lesson 2: Influences on Shepard Classroom Activities 1) Exploring Similar Themes in O’Neill and Shepard 16 2) Exploring Similar Styles in Beckett and Shepard 17 3) Exploring the Influence of Music on Shepard 18 Lesson 3: Inspired by Shepard Classroom Activities 1) Reading Samples of Shepard 28 2) Creative Writing Inspired by Shepard 29 3) Directing One’s Own Work 29 Lesson 4: What Are You Seeing Classroom Activities 1) Pieces Being Performed 33 2) Statues 34 3) Staging a Monologue 36 Lesson 5: Reflection Classroom Activities 1) Written Reflection 44 2) Putting It All Together 45 2 About Profile Theatre Profile Theatre was founded in 1997 with the mission of celebrating the playwright’s contribution to live theater. To that end, Profile programs a full season of the work of a single playwright. This provides our community with the opportunity to deeply engage with the work of our featured playwright through performances, readings, lectures and talkbacks, a unique experience in Portland. Our Mission realized... Profile invites our audiences to enter a writer’s world for a full season of plays and events. -

William and Mary Theatre Main Stage Productions

WILLIAM AND MARY THEATRE MAIN STAGE PRODUCTIONS 1926-1927 1934-1935 1941-1942 The Goose Hangs High The Ghosts of Windsor Park Gas Light Arms and the Man Family Portrait 1927-1928 The Romantic Age The School for Husbands You and I The Jealous Wife Hedda Gabler Outward Bound 1935-1936 1942-1943 1928-1929 The Unattainable Thunder Rock The Enemy The Lying Valet The Male Animal The Taming of the Shrew The Cradle Song *Bach to Methuselah, Part I Candida Twelfth Night *Man of Destiny Squaring the Circle 1929-1930 1936-1937 The Mollusc Squaring the Circle 1943-1944 Anna Christie Death Takes a Holiday Papa is All Twelfth Night The Gondoliers The Patriots The Royal Family A Trip to Scarborough Tartuffe Noah Candida 1930-1931 Vergilian Pageant 1937-1938 1944-1945 The Importance of Being Earnest The Night of January Sixteenth Quality Street Just Suppose First Lady Juno and the Paycock The Merchant of Venice The Mikado Volpone Enter Madame Liliom Private Lives 1931-1932 1938-1939 1945-1946 Sun-Up Post Road Pygmalion Berkeley Square RUR Murder in the Cathedral John Ferguson The Pirates of Penzance Ladies in Retirement As You Like It Dear Brutus Too Many Husbands 1932-1933 1939-1940 1946-1947 Outward Bound The Inspector General Arsenic and Old Lace Holiday Kind Lady Arms and the Man The Recruiting Officer Our Town The Comedy of Errors Much Ado About Nothing Hay Fever Joan of Lorraine 1933-1934 1940-1941 1947-1948 Quality Street You Can’t Take It with You The Skin of Our Teeth Hotel Universe Night Must Fall Blithe Spirit The Swan Mary of Scotland MacBeth -

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

David Rabe's Good for Otto Gets Star Studded Cast with F. Murray Abraham, Ed Harris, Mark Linn-Baker, Amy Madigan, Rhea Perl

David Rabe’s Good for Otto Gets Star Studded Cast With F. Murray Abraham, Ed Harris, Mark Linn-Baker, Amy Madigan, Rhea Perlman and More t2conline.com/david-rabes-good-for-otto-gets-star-studded-cast-with-f-murray-abraham-ed-harris-mark-linn-baker-amy- madigan-rhea-perlman-and-more/ Suzanna January 30, 2018 Bowling F. Murray Abraham (Barnard), Kate Buddeke (Jane), Laura Esterman (Mrs. Garland), Nancy Giles (Marci), Lily Gladstone (Denise), Ed Harris (Dr. Michaels), Charlotte Hope (Mom), Mark Linn- Baker (Timothy), Amy Madigan (Evangeline), Rileigh McDonald (Frannie), Kenny Mellman (Jerome), Maulik Pancholy (Alex), Rhea Perlman (Nora) and Michael Rabe (Jimmy), will lite up the star in the New York premiere of David Rabe’s Good for Otto. Rhea Perlman took over the role of Nora, after Rosie O’Donnell, became ill. Directed by Scott Elliott, this production will play a limited Off-Broadway engagement February 20 – April 1, with Opening Night on Thursday, March 8 at The Pershing Square Signature Center (The Alice Griffin Jewel Box Theatre, 480 West 42nd Street). Through the microcosm of a rural Connecticut mental health center, Tony Award-winning playwright David Rabe conjures a whole American community on the edge. Like their patients and their families, Dr. Michaels (Ed Harris), his colleague Evangeline (Amy Madigan) and the clinic itself teeter between breakdown and survival, wielding dedication and humanity against the cunning, inventive adversary of mental illness, to hold onto the need to fight – and to live. Inspired by a real clinic, Rabe finds humor and compassion in a raft of richly drawn characters adrift in a society and a system stretched beyond capacity. -

Announcing a VIEW from the BRIDGE

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE “One of the most powerful productions of a Miller play I have ever seen. By the end you feel both emotionally drained and unexpectedly elated — the classic hallmark of a great production.” - The Daily Telegraph “To say visionary director Ivo van Hove’s production is the best show in the West End is like saying Stonehenge is the current best rock arrangement in Wiltshire; it almost feels silly to compare this pure, primal, colossal thing with anything else on the West End. A guileless granite pillar of muscle and instinct, Mark Strong’s stupendous Eddie is a force of nature.” - Time Out “Intense and adventurous. One of the great theatrical productions of the decade.” -The London Times DIRECT FROM TWO SOLD-OUT ENGAGEMENTS IN LONDON YOUNG VIC’S OLIVIER AWARD-WINNING PRODUCTION OF ARTHUR MILLER’S “A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE” Directed by IVO VAN HOVE STARRING MARK STRONG, NICOLA WALKER, PHOEBE FOX, EMUN ELLIOTT, MICHAEL GOULD IS COMING TO BROADWAY THIS FALL PREVIEWS BEGIN WEDNESDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 21 OPENING NIGHT IS THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 12 AT THE LYCEUM THEATRE Direct from two completely sold-out engagements in London, producers Scott Rudin and Lincoln Center Theater will bring the Young Vic’s critically-acclaimed production of Arthur Miller’s A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE to Broadway this fall. The production, which swept the 2015 Olivier Awards — winning for Best Revival, Best Director, and Best Actor (Mark Strong) —will begin previews Wednesday evening, October 21 and open on Thursday, November 12 at the Lyceum Theatre, 149 West 45 Street. -

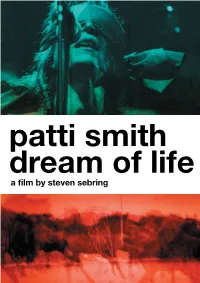

Patti DP.Indd

patti smith dream of life a film by steven sebring THIRTEEN/WNET NEW YORK AND CLEAN SOCKS PRESENT PATTI SMITH AND THE BAND: LENNY KAYE OLIVER RAY TONY SHANAHAN JAY DEE DAUGHERTY AND JACKSON SMITH JESSE SMITH DIRECTORS OF TOM VERLAINE SAM SHEPARD PHILIP GLASS BENJAMIN SMOKE FLEA DIRECTOR STEVEN SEBRING PRODUCERS STEVEN SEBRING MARGARET SMILOW SCOTT VOGEL PHOTOGRAPHY PHILLIP HUNT EXECUTIVE CREATIVE STEVEN SEBRING EDITORS ANGELO CORRAO, A.C.E, LIN POLITO PRODUCERS STEVEN SEBRING MARGARET SMILOW CONSULTANT SHOSHANA SEBRING LINE PRODUCER SONOKO AOYAGI LEOPOLD SUPERVISING INTERNATIONAL PRODUCERS JUNKO TSUNASHIMA KRISTIN LOVEJOY DISTRIBUTION BY CELLULOID DREAMS Thirteen / WNET New York and Clean Socks present Independent Film Competition: Documentary patti smith dream of life a film by steven sebring USA - 2008 - Color/B&W - 109 min - 1:66 - Dolby SRD - English www.dreamoflifethemovie.com WORLD SALES INTERNATIONAL PRESS CELLULOID DREAMS INTERNATIONAL HOUSE OF PUBLICITY 2 rue Turgot Sundance office located at the Festival Headquarters 75009 Paris, France Marriott Sidewinder Dr. T : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0370 F : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0371 Jeff Hill – cell: 917-575-8808 [email protected] E: [email protected] www.celluloid-dreams.com Michelle Moretta – cell: 917-749-5578 E: [email protected] synopsis Dream of Life is a plunge into the philosophy and artistry of cult rocker Patti Smith. This portrait of the legendary singer, artist and poet explores themes of spirituality, history and self expression. Known as the godmother of punk, she emerged in the 1970’s, galvanizing the music scene with her unique style of poetic rage, music and trademark swagger. -

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO Faculdade De Filosofia, Letras E Ciências Humanas Departamento De Teoria Literária

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas Departamento de Teoria Literária Lígia Razera Gallo O desequilíbrio familiar e a identidade americana nas peças de Sam Shepard São Paulo 2011 1 UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas Departamento de Teoria Literária Lígia Razera Gallo O desequilíbrio familiar e a identidade americana nas peças de Sam Shepard (versão corrigida) São Paulo 2011 Ligia Razera Gallo O desequilíbrio familiar e a identidade americana nas peças de Sam Shepard Tese apresentada ao Departamento de Letras Modernas da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo, como parte dos requisitos para a obtenção do título de Mestre na área de Teoria Literária e Literatura Comparada, sob a orientação do Prof. Dr. Fábio Rigatto de Souza Andrade. (versão corrigida) “de acordo” _____________________________________________________ SÃO PAULO 2011 Serviço de Biblioteca e Documentação da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humans da Universidade de São Paulo. Gallo, Ligia Razera O desequilíbrio familiar e a identidade americana nas peças de Sam Shepard / Ligia Razera Gallo; orientador Fábio Rigatto de Souza Andrade.─ São Paulo, 2011. 200 f. Tese (Mestrado – Programa de Pós-Graduação em Teoria Literária e Literatura Comparada. Área de concentração: Teoria Literária e Literatura Comparada) – Departamento de Teoria Literária da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo. (versão corrigida) 1. Teatro norte-americano – Século 20. 2. Identidade americana 3. Crítica teatral FOLHA DE APROVAÇÃO LIGIA RAZERA GALLO O desequilíbrio familiar e a identidade americana nas peças de Sam Shepard Tese apresentada ao Departamento de Letras Modernas da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo, como parte dos requisitos para a obtenção do título de Mestre na área de Literatura Comparada, sob a orientação do Prof. -

Sam Shepard's Dramaturgical Strategies Susan

Fall 1988 71 Estrangement and Engagement: Sam Shepard's Dramaturgical Strategies Susan Harris Smith Current scholarship reveals an understandable preoccupation with and confusion over Sam Shepard's most prominent characteristics, his language and imagery, both of which are seminal features of his technical innovation. In their attempts to describe or define Shepard's idiosyncratic dramaturgy, critics variously have called it absurdist, surrealistic, mythic, Brechtian, and even Artaudian. Most critics, too, are concerned primarily with his themes: physical violence, erotic dynamism, and psychological dissolution set against the cultural wasteland of modern America (Marranca, ed.). But in focusing on Shepard's imagery, language, and themes, some critics ignore theatrical performance. Beyond observing that many of Shepard's role-playing characters engage in power struggles with each other, few critics have concerned themselves with Shepard's structural strategies or with the ways in which he manipulates his audience. One who has addressed the issue, Bonnie Marranca, writes: Characters often engage in, "performance": they create roles for themselves and dialogue, structuring new realities. ... It might be called an aesthetics of actualism. In other words, the characters act themselves out, even make them• selves up, through the transforming power of their imagina• tion. An Assistant Professor of English at the University of Pittsburgh and the author of Masks in Modern Drama, Susan Harris Smith is currently working on a book on American drama. A shorter version of this article was presented at the South• eastern Modern Languages Association in 1985. 72 Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism Because the characters are so free of fixed reality, their imagination plays a key role in the narratives. -

Buried Child by Sam Shepard

MEDIA CONTACT: Bernie Fabig, Marketing & Publicity Manager 310-756-2428 • [email protected] The third production of A Noise Within’s 2019-2020 Season: THEY PLAYED WITH FIRE Buried Child By Sam Shepard Directed by Julia Rodriguez-Elliott Oct. 19 – Nov. 23, 2019 Pasadena, Calif. (Oct. 19, 2019) – A Noise Within (ANW), California’s acclaimed classic repertory theatre company, is proud to present Sam Shepard’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Buried Child, directed by ANW Producing Artistic Director Julia Rodriguez-Elliott. Shepard’s remarkable masterpiece Buried Child will run Oct. 13 through Nov. 23, 2019 with press performances on Saturday, Oct. 19 at 8 p.m. and Sunday, Oct. 20 at 2 p.m. Set in America’s heartland, Sam Shepard’s powerful Pulitzer Prize-winning play details, with wry humor, the disintegration of the American Dream. When 22-year-old Vince unexpectedly shows up at the family farm with his girlfriend Shelly, no one recognizes him. So begins the unraveling of dark secrets. A surprisingly funny look at disillusionment and morality, Shepard’s masterpiece is the family reunion no one anticipated. “Buried Child is wickedly funny,” said Producing Artistic Director Julia Rodriguez-Elliott. “Sam Shepard has an uncanny way of bringing out the humor in dysfunction. There’s something familiar, yet not familiar about this family. It’s at once disconcertingly recognizable and inexplicably strange.” - more - MEDIA CONTACT: Bernie Fabig, Marketing & Publicity Manager 310-756-2428 • [email protected] In Buried Child, comedy meets the absurd in a bizarre twist on the family drama that scorches with a powerful commentary on the “American Dream” and what happens when a community simmers in neglect, resentment, and disowned memory. -

The Inventory of the Sam Shepard Collection #746

The Inventory of the Sam Shepard Collection #746 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Shepard, Srun Sept,1~77 - Jan,1979 Outline of Inventory I. MANUSCRIPTS A. Plays B. Poetry c. Journal D. Short Prose E. Articles F. Juvenilia G. By Other Authors II. NOTES III. PRINTED MATTER A, By SS B. Reviews and Publicity C. Biographd:cal D. Theatre Programs and Publicity E. Miscellany IV. AWARDS .•, V. FINANCIAL RECOR.EB A. Receipts B. Contracts and Ageeements C. Royalties VI. DRAWINGS AND PHOTOGRAPHS VII. CORRESPONDENCE VIII.TAPE RECORDINGS Shepard, Sam Box 1 I. MANUSCRIPTS A. Plays 1) ACTION. Produced in 1975, New York City. a) Typescript with a few bolo. corr. 2 prelim. p., 40p. rn1) b) Typescript photocopy of ACTION "re-writes" with holo. corr. 4p. marked 37640. (#2) 2) ANGEL CITY, rJrizen Books, 1976. Produced in 1977. a) Typescript with extensive holo. corr. and inserts dated Oct. 1975. ca. 70p. (ft3) b) Typescript with a few holo. corr. 4 prelim. p., 78p. (#4) c) Typescript photocopy with holo. markings and light cues. Photocopy of r.ouqh sketch of stage set. 1 prelim. p., 78p. ms) 3) BURIED CHILD a) First draft, 1977. Typescript with re~isions and holo. corr. 86p. (#6) b) Typescript revisions. 2p. marked 63, 64. (#6) 4) CALIFORNIA HEART ATTACK, 1974. ,•. ' a) Typescript with holo. corr. 23p. (#7) ,, 5) CURSE OF THE STARVING CLASS, Urizen Books, 1976. a) Typescript with holo. corr. 1 prelim. p., 104p. ms) b) Typescript photocopy with holo. corr. 1 prelim. p. 104p. (#9) c) Typescript dialogue and stage directions, 9p. numbered 1, 2, and 2-8. -

Signótica 17 V. 1

FIGURAL FORMS OF KNOWLEDGE: A STUDY OF THE SHORT PROSE OF SAM SHEPARD RICARDO DA SILVA SOBREIRA* ABSTRACT The paratactical style and the indeterminacies are literary strategies that resist the conventional impulse of totalizing the elements projected by the text, because instead of selecting the aspects of reality and subordinating the images and perceptions into a hierarchy, the use of these techniques favors the juxtaposition of multiple perspectives and the frustration of narrative closure. Thus, the use of parataxis and indeterminacies in the collection of short stories Great Dream of Heaven (2002), by the American author Sam Shepard, tends to challenge the process of meaning production through the progressive erasure of narrative “certainties”. K EY WORDS : Postmodern, indeterminacy, parataxis, narrative, Sam Shepard. Because of its careful strategies of omission and delicate condensation of meaning, the short forms of prose have always challenged authors, readers, and, above all, critics. As the theories designed for longer forms such as the novel do not seem to fit well the short stories, the critics have realized that it was necessary to develop separate theories that could apply to these cultural products. Since then, theorists as diverse as Vladimir Propp, Ian Reid, Leonard Ashley, Julio Cortázar, Nádia Gotlib, among many others have tried to analyze the specific narrative procedures of the short story. But some of the fiction produced during the last three decades seem to offer interesting challenges to those strategies of interpretation. This may sound somewhat awkward since there are not any absolutely * Doutorando na Universidade Estadual Paulista (São José do Rio Preto, SP).