Stories from the Musselman Library Collection Robin Wagner Gettysburg College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Eisenhower Christmas 2 by ALEX J

November / December 2018 An Eisenhower Christmas 2 BY ALEX J. HAYES What’s Inside: A publication of CONTRIBUTING ADVERTISING The Gettysburg Companion is published bimonthly and Gettysburg Times, LLC WRITERS SALES distributed throughout the area. PO Box 3669, Gettysburg, PA The Gettysburg Companion can be mailed to you for Holly Fletcher Brooke Gardner $27 per year (six issues) or $42 for two years (12 issues). Discount rates are available for multiple subscriptions. You PUBLISHER Jim Hale David Kelly can subscribe by sending a check, money order or credit Harry Hartman Alex J. Hayes Tanya Parsons card information to the address above, going online to gettysburgcompanion.com or by calling 717-334-1131. EDITOR Mary Grace Keller Nancy Pritt All information contained herein is protected by copyright Carolyn Snyder and may not be used without written permission from the Alex J. Hayes PHOTOGRAPHY publisher or editor. MAGAZINE DESIGN John Armstrong Information on advertising can be obtained by calling the Jim Hale Gettysburg Times at 717-334-1131. Kristine Celli Visit GettysburgCompanion.com for additional Darryl Wheeler information on advertisers. 3 November / DecemberNOV. 8: Adams County Community Foundation Giving Spree Gettysburg Area Middle School www.adamscountycf.org CHECK WEBSITES FOR THE MANY NOV. 2: NOV. 16 - 17: 4-H Benefit Auction Remembrance Day Ball EVENTS IN NOVEMBER Agricultural & Gettysburg Hotel & DECEMBER: Natural Resources Center www.remembrancedayball.com 717-334-6271 NOV. 17: MAJESTIC THEATER NOV. 2: National Civil War Ball www.gettysburgmajestic.org First Friday, Gettysburg Style Eisenhower Inn & Conference Center Support Our Veterans www.gettysburgball.com ARTS EDUCATION CENTER www.gettysburgretailmerchants.com adamsarts.org NOV. -

On the Banks of Buck Creek

spring 2009 On The Banks Of Buck Creek Alumnus And Professor Team Up To Transform Springfield Waterway Wittenberg Magazine is published three times a year by Wittenberg University, Office of University Communications. Editor Director of University Communications Karen Saatkamp Gerboth ’93 Graphic Designer Joyce Sutton Bing Design Director of News Services and Sports Information Ryan Maurer Director of New Media and Webmaster Robert Rafferty ’02 Photo Editor Erin Pence ’04 Coordinator of University Communications Phyllis Eberts ’00 Class Notes Editor Charyl Castillo Contributors Gabrielle Antoniadis Ashley Carter ’09 Phyllis Eberts ’00 Robbie Gantt Erik Larkin ’09 Karamagi Rujumba ’02 Brian Schubert ’09 Brad Tucker Address correspondence to: Editor, Wittenberg Magazine Wittenberg University P.O. Box 720 Springfield, Ohio 45501-0720 Phone: (937) 327-6111 Fax: (937) 327-6112 E-mail: [email protected] www.wittenberg.edu Articles are expressly the opinions of the authors and do not necessarily represent official university policy. We reserve the right to edit correspondence for length and accuracy. We appreciate photo submissions, but because of their large number, we cannot return them. Wittenberg University does not discriminate against otherwise qualified persons on the basis of race, creed, color, religion, national or ethnic origin, sex, sexual orientation, age, or disability unrelated to the student’s course of study, in admission or access to the university’s academic programs, activities, and facilities that are generally available to students, or in the administration of its educational policies, admissions policies, scholarship and loan programs, and athletic and other college-administered programs. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Editor, Wittenberg Magazine Wittenberg University P.O. -

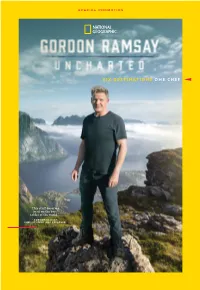

Gordon Ramsay Uncharted

SPECIAL PROMOTION SIX DESTINATIONS ONE CHEF “This stuff deserves to sit on the best tables of the world.” – GORDON RAMSAY; CHEF, STUDENT AND EXPLORER SPECIAL PROMOTION THIS MAGAZINE WAS PRODUCED BY NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CHANNEL IN PROMOTION OF THE SERIES GORDON RAMSAY: CONTENTS UNCHARTED PREMIERES SUNDAY JULY 21 10/9c FEATURE EMBARK EXPLORE WHERE IN 10THE WORLD is Gordon Ramsay cooking tonight? 18 UNCHARTED TRAVEL BITES We’ve collected travel stories and recipes LAOS inspired by Gordon’s (L to R) Yuta, Gordon culinary journey so that and Mr. Ten take you can embark on a spin on Mr. Ten’s your own. Bon appetit! souped-up ride. TRAVEL SERIES GORDON RAMSAY: ALASKA Discover 10 Secrets of UNCHARTED Glacial ice harvester Machu Picchu In his new series, Michelle Costello Gordon Ramsay mixes a Manhattan 10 Reasons to travels to six global with Gordon using ice Visit New Zealand destinations to learn they’ve just harvested from the locals. In from Tracy Arm Fjord 4THE PATH TO Go Inside the Labyrin- New Zealand, Peru, in Alaska. UNCHARTED thine Medina of Fez Morocco, Laos, Hawaii A rare look at Gordon and Alaska, he explores Ramsay as you’ve never Road Trip: Maui the culture, traditions seen him before. and cuisine the way See the Rich Spiritual and only he can — with PHOTOS LEFT TO RIGHT: ERNESTO BENAVIDES, Cultural Traditions of Laos some heart-pumping JON KROLL, MARK JOHNSON, adventure on the side. MARK EDWARD HARRIS Discover the DESIGN BY: Best of Anchorage MARY DUNNINGTON 2 GORDON RAMSAY: UNCHARTED SPECIAL PROMOTION 3 BY JILL K. -

A Multimedia Website for the Battle of Gettysburg

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2004 A multimedia website for the Battle of Gettysburg Mark Norman Rasmussen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Educational Methods Commons Recommended Citation Rasmussen, Mark Norman, "A multimedia website for the Battle of Gettysburg" (2004). Theses Digitization Project. 2593. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2593 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A MULTIMEDIA WEBSITE FOR THE BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Education: Instructional Technology by Mark Norman Rasmussen September 2004 A MULTIMEDIA WEBSITE FOR THE BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Mark Norman Rasmussen September 2004 Approved by: Dr. Brian Newberry, 'Chair, Dateilk Science, Math, and•Technolo« .Education Dr. Silvester Robertson, Education © 2004 Mark Norman Rasmussen •• ABSTRACT This thesis explains the development of a website for eighth grader's ■ about’ the Battle of Gettysburg. There is a summary of the battle which happened in July of 1863. A review of literature supporting the design of the website follows. There is an explanation of how the website was designed. The back of the book contains a CD-ROM that holds the website. -

Craftsmanship Renovation of an Underground Railroad Safe-House in Gettysburg by Peter H

Craftsmanship Renovation of an Underground Railroad Safe-house in Gettysburg By Peter H. Michael This article appeared in Construction Executive magazine in May, 2013. The renovation by Morgan-Keller Construction written about here won a first-place national prize for historic reno- vation. ❦ When Dwight Pryor was married in the chapel of the historic Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania in 1993, he never imagined that he would revisit the school in charge of the delicate job of expertly restoring its oldest, most revered building. Constructed in 1831-32 for $10,500 and named for the Seminary's first president, Schmucker Hall was first used for all of the Seminary's functions, then as a student dormitory as the school con- structed other buildings. The first engagement of the Civil War Battle of Gettysburg was fought on Seminary Ridge in and around Schmucker Hall which was commandeered by both armies as a hospital where thousands of casualties were treated and a few precious artifacts were left be- hind. The seven-level stone-and-brick landmark comprises four stories, basement, attic and cu- pola. The Seminary itself made civil rights history from its founding, through the Civil War and beyond. The Seminary's barn, no longer extant, is among the three to four percent of today's claimed Underground Railroad sites having conclusive documentation of involvement in the dangerous, illegal, clandestine moral network which shepherded tens of thousands of freedom seekers to northern states and Canada. The Seminary's role in abolitionism was early, active, bold and, more than once, punished. -

In Response to Bengt Hagglund: Ihe Importance of Epistemology for Luther's and Melanchthon's Theology

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY Volume 44, Numbers 2-3 -- JULY 1980 Can the Lutheran Confessions Have Any Meaning 450 Years Later?.................... Robert D. Preus 104 Augustana VII and the Eclipse of Ecumenism ....................................... Siegbert W. Becker 108 Melancht hon versus Luther: The Contemporary Struggle ......................... Bengt Hagglund 123 In Response to Bengt Hagglund: Ihe Importance of Epistemology for Luther's and Melanchthon's Theology .............. Wilbert H. Rosin 134 Did Luther and Melanchthon Agree on the Real Presence?.. .................................. David P. Scaer 14 1 Luther and Melanchthon in America.. .................. ..... .......................C. George Fry 148 Luther's Contribution to the Augsburg Confession .............................................. Eugene F. Klug 155 Fanaticism as a Theological Category in the Lutheran Confessions ............................... Paul L. Maier 173 Homiletical Studies 182 In Response to Bengt Hagglund: Luther and Melanchthon in America C. George Fry It has always struck me as strangely appropriate that the Protestant Reformation and the discovery of America occurred simultaneously. When Martin Luther was nine, Christopher Columbus landed in the Bahamas; in 15 19, while he debated Dr. John Eck at Leipzig, a fellow-subject of Emperor Charles V, Hernando Cortez, began the conquest of Mexico. Philip Melanc ht hon, the "Great Confessor," was com.posing the Augustana at about the time Francisco Pizarro was occupying the Inca Empire in Peru. By the time of Melancht hon's death in 1560, the Americas had been opened up to European settlement. A related theme of equal interest is that of the American dis- covery of the Reformation. Or, more properly, the recovery by Lutherans in the United States of the history and theology of the Reformers. -

Welcome to the Championship

Welcome To The Championship Table of Contents Sections I. General Information Primary Contacts, Schedule of Events, Press Information & Tournament Brackets II. Teams Bowdoin, Denison, Emory, Gustavus Adolphus, Mary Washington, Pomona-Pitzer, Washington & Lee, and Williams III. The Numbers NCAA Championship Series Record Book, NCAA Division III Championship Record Book, Past Championships Results Brown Outdoor Complex and Swanson Indoor Tennis Center Site of 2008 NCAA Division III Women’s Tennis Championships Dear Members of the Media, On behalf of Gustavus Adolphus College, I would like to extend a hearty welcome to the media covering the 2008 NCAA Division III Women’s Tennis Championships. We welcome you to the Minnesota River Valley and hope that you enjoy your visit to the St. Peter/Mankato area. If there is anything we can do to make your time here more accommodating, please do not hesitate to ask. The stage is set for a fantastic championship, we hope you enjoy your time here. Sincerely, Tim Kennedy Gustavus Adolphus Sports Information Director 2008 NCAA Division III Women’s Tennis Tournament Contacts NCAA Division III Women’s Tennis Committee James Cohagan, University of Mary Hardin-Baylor, Chair George Kolb, Roger Williams University Scott Wills, Ohio Northern University Ximena Moore, Huntingdon College NCAA Championship Staff Liason Liz Suscha Executive Tournament Director Dr. Alan I. Molde, Gustavus Director of Athletics Office Phone: 507-933-7622 [email protected] Tournament Managers Mike Stehlik, Gustavus women’s soccer coach -

65 Pop Culture Trivia Questions and Answers

Trivia Questions Overview Are you a walking encyclopedia for all things entertainment? Do you pride yourself on knowing the names and order of Kris Jenner‘s offspring? Or can you name all European countries? Look no further, we have provided 4 sections with questions and answers based on various subjects, age and interests. Choose which category or questions you think would be a good fit for your event. These are only a guide, feel free to make your own questions! • 65 Pop Culture Trivia Questions and Answers • 90 Fun Generic Trivia Questions and Answers • 101 Fun Trivia Questions and Answers for Kids • 150+ Hard Trivia Questions and Answers Section A: 65 Pop Culture Trivia Questions and Answers Questions created by Parade magazine, May 14, 2020 by Alexandra Hurtado ➢ Question: What are the names of Kim Kardashian and Kanye West’s kids? o Answer: North, Saint, Chicago and Psalm. ➢ Question: What is Joe Exotic a.k.a the Tiger King’s real name? o Answer: Joseph Allen Maldonado-assage. ➢ Question: Whose parody Prince George Instagram account inspired the upcoming HBO Max series The Prince? o Answer: Gary Janetti. ➢ Question: How many kids does Angelina Jolie have? o Answer: Six (Maddox, Pax, Zahara, Shiloh, Knox and Vivienne). ➢ Question: Who wrote the book that HBO’s Big Little Lies is based on? o Answer: Liane Moriarty. ➢ Question: Who did Forbes name the youngest “self-made billionaire ever” in 2019? o Answer: Kylie Jenner. 1 ➢ Question: How many times did Ross Geller get divorced on Friends? o Answer: Three times (Carol, Emily, Rachel). ➢ Question: Who was the first Bachelorette in 2003? o Answer: Trista Sutter (née Rehn). -

Celebration Schedule 2012 Provost's Office Gettysburg College

Celebration Celebration 2012 May 5th, 9:00 AM - 5:00 PM Celebration Schedule 2012 Provost's Office Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/celebration Part of the Higher Education Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Provost's Office, "Celebration Schedule 2012" (2012). Celebration. 55. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/celebration/2012/Panels/55 This open access event is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Description Full presentation schedule for Celebration, May 5, 2012 Location Gettysburg College Disciplines Higher Education This event is available at The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/celebration/2012/Panels/55 From the Provost I am most pleased to welcome you to Gettysburg College’s Fourth Annual Colloquium on Undergraduate Research, Creative Activity, and Community Engagement. Today is truly a cause for celebration, as our students present the results of the great work they’ve been engaged in during the past year. Students representing all four class years and from across the disciplines are demonstrating today what’s best about the Gettysburg College experience— intentional collaborations between students and their mentors such that students acquire both knowledge and skills that can be applied to many facets of their future personal and professional lives. The benefits for those who mentor these young adults may, at first, be more difficult to discern. Most of those who engage in mentoring do it because they enjoy being around students who are eager to learn what they have to teach them. -

Murder-Suicide Ruled in Shooting a Homicide-Suicide Label Has Been Pinned on the Deaths Monday Morning of an Estranged St

-* •* J 112th Year, No: 17 ST. JOHNS, MICHIGAN - THURSDAY, AUGUST 17, 1967 2 SECTIONS - 32 PAGES 15 Cents Murder-suicide ruled in shooting A homicide-suicide label has been pinned on the deaths Monday morning of an estranged St. Johns couple whose divorce Victims had become, final less than an hour before the fatal shooting. The victims of the marital tragedy were: *Mrs Alice Shivley, 25, who was shot through the heart with a 45-caliber pistol bullet. •Russell L. Shivley, 32, who shot himself with the same gun minutes after shooting his wife. He died at Clinton Memorial Hospital about 1 1/2 hqurs after the shooting incident. The scene of the tragedy was Mrsy Shivley's home at 211 E. en name, Alice Hackett. Lincoln Street, at the corner Police reconstructed the of Oakland Street and across events this way. Lincoln from the Federal-Mo gul plant. It happened about AFTER LEAVING court in the 11:05 a.m. Monday. divorce hearing Monday morn ing, Mrs Shivley —now Alice POLICE OFFICER Lyle Hackett again—was driven home French said Mr Shivley appar by her mother, Mrs Ruth Pat ently shot himself just as he terson of 1013 1/2 S. Church (French) arrived at the home Street, Police said Mrs Shlv1 in answer to a call about a ley wanted to pick up some shooting phoned in fromtheFed- papers at her Lincoln Street eral-Mogul plant. He found Mr home. Shivley seriously wounded and She got out of the car and lying on the floor of a garage went in the front door* Mrs MRS ALICE SHIVLEY adjacent to -• the i house on the Patterson got out of-'the car east side. -

3/25/13 Andthentheresbea : Messages : 2584-2616 of 3145

3/25/13 andthentheresbea : Messages : 2584-2616 of 3145 Hi, Kevin Help Get new Yahoo! Mail apps Mail My Y! Yahoo! Search Search Web AdChoices vectorlime · [email protected] | Group Owner Edit Membership Start a Group | My Groups | Find a Yahoo! Group andthentheresbea ∙ And Then There's Bea - Just Bea Arthur My Groups Home Messages Message # Go Search: Search Advanced Messages Help Over 1 million people have found joint relief with this Messages secret, now available in Pending Messages Topics Hot Topics Chicago... » Spam? [Delete] Messages 2584 2616 of 3145 Oldest | < Older | Newer > | Newest Start Topic Post Shocking Mood Discovery » Files Delete This is the real reason you’re so Photos unhappy... Messages: Show Message Summaries Sort by Date Links Members #2584 From: "townbridge" <[email protected]> townbridge Men over 40 are seeing Pending Date: Thu Feb 22, 2007 10:00 am Send Email shocking boosts in free Subject: Re: Bea testosterone with this Calendar discovery... Promote --- In [email protected], "becca starr" <rebeccahelaine@...> wrote: Invite > Messages > Hi will bea ever come to Australia?And does she ever get on line or Start Topic > answer mail personally?Thanks. Management Just address an email to > [email protected] Hi Becca Jump to a particular message The Yahoo! Groups Bea is in her 80's so I think she probably won't come to Austrailia a Product Blog 50 per cent chance anyway, I don't think she would come online but she Message # Check it out! does answer or fan mail personally that you send to her. Search Messages Her address is 2000 Old Ranch Rd., Los Angeles, CA 90049-2211 Info Settings Group Information Reply | Messages in this Topic (4) Members: 585 SPONSOR RESULTS Category: Arthur, Beatrice Local Banks Directory Founded: May 27, 2001 yellowpages.com Language: English area ATM, checking & banking services movies online Movies.Inbox.com Yahoo! Groups Tips Watch Online. -

Newsletter 14/12 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 14/12 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 318 - August 2012 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 14/12 (Nr. 318) August 2012 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, liebe Filmfreunde! Mit ein paar Impressionen von der Premiere des Kinofilms DIE KIR- CHE BLEIBT IM DORF, zu der wir am vergangenen Mittwoch ein- geladen waren, möchten wir uns in den Sommerurlaub verabschieden. S ist wie fast jedes Jahr: erst wenn alle Anderen ihren Urlaub schon absolviert haben, sind wir dran. Aber so ein richtiger Urlaub ist das eigentlich gar nicht. Nichts von we- gen faul am Strand liegen und sich Filme in HD auf dem Smartphone reinziehen! Das Fantasy Filmfest Fotos (c) 2012 by Wolfram Hannemann steht bereits vor der Tür und wird uns wieder eine ganze Woche lang von morgens bis spät in die Nacht hinein mit aktueller Filmware ver- sorgen. Wie immer werden wir be- müht sein, möglichst viele der prä- sentierten Filme auch tatsächlich zu sehen. Schließlich wird eine Groß- zahl der Produktionen bereits kurze Zeit nach Ende des Festivals auf DVD und BD verfügbar sein. Und da möchte man natürlich schon vor- her wissen, ob sich ein Kauf lohnen wird. Nach unserer Sommerpause werden wir in einem der Newsletter wieder ein Resümee des Festivals ziehen. Es wird sich also lohnen weiter am Ball zu blei- ben. Ab Montag, den 17.