The Petrobras Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate and Energy Benchmark in Oil and Gas Insights Report

Climate and Energy Benchmark in Oil and Gas Insights Report Partners XxxxContents Introduction 3 Five key findings 5 Key finding 1: Staying within 1.5°C means companies must 6 keep oil and gas in the ground Key finding 2: Smoke and mirrors: companies are deflecting 8 attention from their inaction and ineffective climate strategies Key finding 3: Greatest contributors to climate change show 11 limited recognition of emissions responsibility through targets and planning Key finding 4: Empty promises: companies’ capital 12 expenditure in low-carbon technologies not nearly enough Key finding 5:National oil companies: big emissions, 16 little transparency, virtually no accountability Ranking 19 Module Summaries 25 Module 1: Targets 25 Module 2: Material Investment 28 Module 3: Intangible Investment 31 Module 4: Sold Products 32 Module 5: Management 34 Module 6: Supplier Engagement 37 Module 7: Client Engagement 39 Module 8: Policy Engagement 41 Module 9: Business Model 43 CLIMATE AND ENERGY BENCHMARK IN OIL AND GAS - INSIGHTS REPORT 2 Introduction Our world needs a major decarbonisation and energy transformation to WBA’s Climate and Energy Benchmark measures and ranks the world’s prevent the climate crisis we’re facing and meet the Paris Agreement goal 100 most influential oil and gas companies on their low-carbon transition. of limiting global warming to 1.5°C. Without urgent climate action, we will The Oil and Gas Benchmark is the first comprehensive assessment experience more extreme weather events, rising sea levels and immense of companies in the oil and gas sector using the International Energy negative impacts on ecosystems. -

National Oil Companies: Business Models, Challenges, and Emerging Trends

Corporate Ownership & Control / Volume 11, Issue 1, 2013, Continued - 8 NATIONAL OIL COMPANIES: BUSINESS MODELS, CHALLENGES, AND EMERGING TRENDS Saud M. Al-Fattah* Abstract This paper provides an assessment and a review of the national oil companies' (NOCs) business models, challenges and opportunities, their strategies and emerging trends. The role of the national oil company (NOC) continues to evolve as the global energy landscape changes to reflect variations in demand, discovery of new ultra-deep water oil deposits, and national and geopolitical developments. NOCs, traditionally viewed as the custodians of their country's natural resources, have generally owned and managed the complete national oil and gas supply chain from upstream to downstream activities. In recent years, NOCs have emerged not only as joint venture partners globally with the major oil companies, but increasingly as competitors to the International Oil Companies (IOCs). Many NOCs are now more active in mergers and acquisitions (M&A), thereby increasing the number of NOCs seeking international upstream and downstream acquisition and asset targets. Keywords: National Oil Companies, Petroleum, Business and Operating Models * Saudi Aramco, and King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center (KAPSARC) E-mail: [email protected] Introduction historically have mainly operated in their home countries, although the evolving trend is that they are National oil companies (NOCs) are defined as those going international. Examples of NOCs include Saudi oil companies that have significant shares owned by Aramco (the largest integrated oil and gas company in their parent government, and whose missions are to the world), Kuwait Petroleum Corporation (KPC), work toward the interest of their country. -

2017 Corporate Responsibility Report

2017 corporate responsibility report 2017 corporate responsibility report chevron in Nigeria human energy R chevron in Nigeria 1 2017 corporate responsibility report 2 chevron in Nigeria 2017 corporate responsibility report “We are the partner of choice not only for the goals we achieve but how we achieve them” At the heart of The Chevron Way is our vision … to be the global energy company most admired for its people, partnership and performance. We make this vision a reality by consistently putting our values into practice. The Chevron Way values distinguish us and guide our actions so that we get results the right way. Our values are diversity and inclusion, high performance, integrity and trust, partnership, protecting people and the environment. Cover photo credit: Marc Marriott Produced by: Policy, Government and Public Affairs (PGPA) Department, Chevron Nigeria Limited Design and Layout : Design and Reprographics Unit, Chevron Nigeria Limited chevron in Nigeria 3 2017 corporate responsibility report the chevron way explains who we are, what we do, what we believe and what we plan to accomplish 4 chevron in Nigeria 20172017 ccorporateorpporatee resresponsibilityponssibility reportreport table of contents message from the CMD 6 about chevron in nigeria 7 social investments 8 health 9 education 12 economic development 16 partnership initiatives in the niger delta 20 engaging stakeholders 26 our people 29 operating responsibly 35 nigerian content 41 awards 48 chevron in Nigeria 5 2017 corporate responsibility report of rapid change in the oil and gas industry, our focus remains on delivering that vision in an ethical and sustainable way. Our corporate responsibility focus areas are aligned with our business strategy of delivering industry-leading returns while developing high-value resource opportunities. -

Latin American State Oil Companies and Climate

LATIN AMERICAN STATE OIL COMPANIES AND CLIMATE CHANGE Decarbonization Strategies and Role in the Energy Transition Lisa Viscidi, Sarah Phillips, Paola Carvajal, and Carlos Sucre JUNE 2020 Authors • Lisa Viscidi, Director, Energy, Climate Change & Extractive Industries Program at the Inter-American Dialogue. • Sarah Phillips, Assistant, Energy, Climate Change & Extractive Industries Program at the Inter-American Dialogue. • Paola Carvajal, Consultant, Mining, Geothermal Energy and Hydrocarbons Cluster, Inter-American Development Bank. • Carlos Sucre, Extractives Specialist, Mining, Geothermal Energy and Hydrocarbons Cluster, Inter-American Development Bank. Acknowledgments We would like to thank Columbia University's Center on Global Energy Policy and Philippe Benoit, Adjunct Senior Research Scholar at the Center, for inviting us to participate in the workshop on engaging state-owned enterprises in climate action, a meeting which played an instrumental role in informing this report. We would also like to thank Nate Graham, Program Associate for the Inter-American Dialogue’s Energy, Climate Change & Extractive Industries Program, for his assistance. This report was made possible by support from the Inter-American Development Bank in collaboration with the Inter- American Dialogue’s Energy, Climate Change & Extractive Industries Program. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Inter- American Development Bank, its Board of Directors, or the countries they represent. The views contained herein also do not necessarily reflect the consensus views of the board, staff, and members of the Inter-American Dialogue or any of its partners, donors, and/or supporting institutions. First Edition Cover photo: Pxhere / CC0 Layout: Inter-American Dialogue Copyright © 2020 Inter-American Dialogue and Inter-American Development Bank. -

Pride Drillships Awarded Contracts by BP, Petrobras

D EPARTMENTS DRILLING & COMPLETION N EWS BP makes 15th discovery in ultra-deepwater Angola block Rowan jackup moving SONANGOL AND BP have announced west of Luanda, and reached 5,678 m TVD to Middle East to drill the Portia oil discovery in ultra-deepwater below sea level. This is the fourth discovery offshore Saudi Arabia Block 31, offshore Angola. Portia is the 15th in Block 31 where the exploration well has discovery that BP has drilled in Block 31. been drilled through salt to access the oil- ROWAN COMPANIES ’ Bob The well is approximately 7 km north of the bearing sandstone reservoir beneath. W ell Keller jackup has been awarded a Titania discovery . Portia was drilled in a test results confirmed the capacity of the three-year drilling contract, which water depth of 2,012 m, some 386 km north- reservoir to flow in excess of 5,000 bbl/day . includes an option for a fourth year, for work offshore Saudi Arabia. The Bob Keller recently concluded work Pride drillships in the Gulf of Mexico and is en route to the Middle East. It is expected awarded contracts to commence drilling operations during Q2 2008. Rowan re-entered by BP, Petrobras the Middle East market two years ago after a 25-year absence. This PRIDE INTERNATIONAL HAS contract expands its presence in the announced two multi-year contracts for area to nine jackups. two ultra-deepwater drillships. First, a five-year contract with a BP subsidiary Rowan also has announced a multi- will allow Pride to expand its deepwater well contract with McMoRan Oil & drilling operations and geographic reach Gas Corp that includes re-entering in deepwater drilling basins to the US the Blackbeard Prospect. -

Dilemmas of Brazilian Grand Strategy

STRATEGIC STUDIES INSTITUTE The Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) is part of the U.S. Army War College and is the strategic level study agent for issues related to national security and military strategy with emphasis on geostrate- gic analysis. The mission of SSI is to use independent analysis to conduct strategic studies that develop policy recommendations on: • Strategy, planning and policy for joint and combined employment of military forces; • Regional strategic appraisals; • The nature of land warfare; • Matters affecting the Army’s future; • The concepts, philosophy, and theory of strategy; and • Other issues of importance to the leadership of the Army. Studies produced by civilian and military analysts concern topics having strategic implications for the Army, the Department of De- fense, and the larger national security community. In addition to its studies, SSI publishes special reports on topics of special or immediate interest. These include edited proceedings of conferences and topically-oriented roundtables, expanded trip re- ports, and quick reaction responses to senior Army leaders. The Institute provides a valuable analytical capability within the Army to address strategic and other issues in support of Army par- ticipation in national security policy formulation. Strategic Studies Institute Monograph DILEMMAS OF BRAZILIAN GRAND STRATEGY Hal Brands August 2010 Visit our website for other free publication downloads http://www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil/ To rate this publication click here. The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Depart- ment of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. -

Shell in Brazil: Prospecting for the Future

100 YEARS OF SHELL IN BRAZIL: PROSPECTING FOR THE FUTURE Presentation at the British Consulate in Rio de Janeiro March 11th Flavio Rodrigues Shell Brasil Petróleo Ltda. Copyright of INSERT COMPANY NAME HERE January 2013 1 DEFINITIONS AND CAUTIONARY NOTE The companies in which Royal Dutch Shell plc directly and indirectly owns investments are separate entities. In this presentation “Shell”, “Shell group” and “Royal Dutch Shell” are sometimes used for convenience where references are made to Royal Dutch Shell plc and its subsidiaries in general. Likewise, the words “we”, “us” and “our” are also used to refer to subsidiaries in general or to those who work for them. These expressions are also used where no useful purpose is served by identifying the particular company or companies. “Shell Brasil Petróleo Ltda”, ‘‘Subsidiaries’’, “Shell subsidiaries” and “Shell companies” as used in this presentation refer to companies in which Royal Dutch Shell either directly or indirectly has control, by having either a majority of the voting rights or the right to exercise a controlling influence. The companies in which Shell has significant influence but not control are referred to as “associated companies” or “associates” and companies in which Shell has joint control are referred to as “jointly controlled entities”. In this presentation, associates and jointly controlled entities are also referred to as “equity- accounted investments”. The term “Shell interest” is used for convenience to indicate the direct and/or indirect ownership interest held by Shell in a venture, partnership or company, after exclusion of all third-party interest. This presentation contains forward-looking statements concerning the financial condition, results of operations and businesses of Royal Dutch Shell. -

Foreign Investment in the Oil Sands and British Columbia Shale Gas

Canadian Energy Research Institute Foreign Investment in the Oil Sands and British Columbia Shale Gas Jon Rozhon March 2012 Relevant • Independent • Objective Foreign Investment in the Oil Sands and British Columbia Shale Gas 1 Foreign Investment in the Oil Sands There has been a steady flow of foreign investment into the oil sands industry over the past decade in terms of merger and acquisition (M&A) activity. Out of a total CDN$61.5 billion in M&A’s, approximately half – or CDN$30.3 billion – involved foreign companies taking an ownership stake. These funds were invested in in situ projects, integrated projects, and land leases. As indicated in Figure 1, US and Chinese companies made the most concerted efforts to increase their profile in the oil sands, investing 2/3 of all foreign capital. The US and China both invested in a total of seven different projects. The French company, Total SA, has also spread its capital around several projects (four in total) while Royal Dutch Shell (UK), Statoil (Norway), and PTT (Thailand) each opted to take large positions in one project each. Table 1 provides a list of all foreign investments in the oil sands since 2004. Figure 1: Total Oil Sands Foreign Investment since 2003, Country of Origin Korea 1% Thailand Norway 6% UK 7% 2% US France 33% 18% China 33% Source: Canoils. Foreign Investment in the Oil Sands and British Columbia Shale Gas 2 Table 1: Oil Sands Foreign Investment Deals Year Country Acquirer Brief Description Total Acquisition Cost (000) 2012 China PetroChina 40% interest in MacKay River 680,000 project from AOSC 2011 China China National Offshore Acquisition of OPTI Canada 1,906,461 Oil Corporation 2010 France Total SA Alliance with Suncor. -

Climate and Energy Benchmark in Oil and Gas

Climate and Energy Benchmark in Oil and Gas Total score ACT rating Ranking out of 100 performance, narrative and trend 1 Neste 57.4 / 100 8.1 / 20 B 2 Engie 56.9 / 100 7.9 / 20 B 3 Naturgy Energy 44.8 / 100 6.8 / 20 C 4 Eni 43.6 / 100 7.3 / 20 C 5 bp 42.9 / 100 6.0 / 20 C 6 Total 40.7 / 100 6.1 / 20 C 7 Repsol 38.1 / 100 5.0 / 20 C 8 Equinor 37.9 / 100 4.9 / 20 C 9 Galp Energia 36.4 / 100 4.3 / 20 C 10 Royal Dutch Shell 34.3 / 100 3.4 / 20 C 11 ENEOS Holdings 32.4 / 100 2.6 / 20 C 12 Origin Energy 29.3 / 100 7.3 / 20 D 13 Marathon Petroleum Corporation 24.8 / 100 4.4 / 20 D 14 BHP Group 22.1 / 100 4.3 / 20 D 15 Hellenic Petroleum 20.7 / 100 3.7 / 20 D 15 OMV 20.7 / 100 3.7 / 20 D Total score ACT rating Ranking out of 100 performance, narrative and trend 17 MOL Magyar Olajes Gazipari Nyrt 20.2 / 100 2.5 / 20 D 18 Ampol Limited 18.8 / 100 0.9 / 20 D 19 SK Innovation 18.6 / 100 2.8 / 20 D 19 YPF 18.6 / 100 2.8 / 20 D 21 Compania Espanola de Petroleos SAU (CEPSA) 17.9 / 100 2.5 / 20 D 22 CPC Corporation, Taiwan 17.6 / 100 2.4 / 20 D 23 Ecopetrol 17.4 / 100 2.3 / 20 D 24 Formosa Petrochemical Corp 17.1 / 100 2.2 / 20 D 24 Cosmo Energy Holdings 17.1 / 100 2.2 / 20 D 26 California Resources Corporation 16.9 / 100 2.1 / 20 D 26 Polski Koncern Naftowy Orlen (PKN Orlen) 16.9 / 100 2.1 / 20 D 28 Reliance Industries 16.7 / 100 1.0 / 20 D 29 Bharat Petroleum Corporation 16.0 / 100 1.7 / 20 D 30 Santos 15.7 / 100 1.6 / 20 D 30 Inpex 15.7 / 100 1.6 / 20 D 32 Saras 15.2 / 100 1.4 / 20 D 33 Qatar Petroleum 14.5 / 100 1.1 / 20 D 34 Varo Energy 12.4 / 100 -

2013 Financial and Operating Review

Financial & Operating Review 2 013 Financial & Operating Summary 1 Delivering Profitable Growth 3 Global Operations 14 Upstream 16 Downstream 58 Chemical 72 Financial Information 82 Frequently Used Terms 90 Index 94 General Information 95 COVER PHOTO: Liquefied natural gas (LNG) produced at our joint ventures with Qatar Petroleum is transported to global markets at constant temperature and pressure by dedicated carriers designed and built to meet the most rigorous safety standards. Statements of future events or conditions in this report, including projections, targets, expectations, estimates, and business plans, are forward-looking statements. Actual future results, including demand growth and energy mix; capacity growth; the impact of new technologies; capital expenditures; project plans, dates, costs, and capacities; resource additions, production rates, and resource recoveries; efficiency gains; cost savings; product sales; and financial results could differ materially due to, for example, changes in oil and gas prices or other market conditions affecting the oil and gas industry; reservoir performance; timely completion of development projects; war and other political or security disturbances; changes in law or government regulation; the actions of competitors and customers; unexpected technological developments; general economic conditions, including the occurrence and duration of economic recessions; the outcome of commercial negotiations; unforeseen technical difficulties; unanticipated operational disruptions; and other factors discussed in this report and in Item 1A of ExxonMobil’s most recent Form 10-K. Definitions of certain financial and operating measures and other terms used in this report are contained in the section titled “Frequently Used Terms” on pages 90 through 93. In the case of financial measures, the definitions also include information required by SEC Regulation G. -

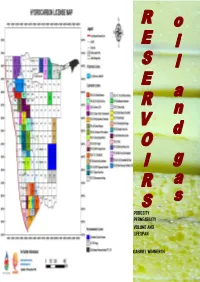

Porosity Permeability Volume and Lifespan Gabriel Wimmerth

POROSITY PERMEABILITY VOLUME AND LIFESPAN GABRIEL WIMMERTH 1 THE POROSITY OF A RESERVOIR DETERMINES THE QUANTITY OF OIL AND GAS. THE MORE PORES A RESERVOIR CONTAINS THE MORE QUANTITY, VOLUME OF OIL AND GAS IS PRESENT IN A RESERVOIR. BY GABRIEL KEAFAS KUKU PLAYER WIMMERTH DISSERTATION PRESENTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTORATE IN PETROLEUM ENGINEERING In the Department of Engineering and Science at the Atlantic International University, Hawaii, Honolulu, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Promoter: Dr. Franklin Valcin President/Academic Dean at Atlantic International University October 2015 2 DECLARATION I declare by submitting this thesis, dissertation electronically that that the comprehensive, detailed and the entire piece of work is my own, original work that I am the sole owner of the copyright thereof(unless to the extent otherwise stated) and that I have not previously submitted any part of the work in obtaining any other qualification. Signature: Date: 10 October 2015 Copyright@2015 Atlantic International University All rights reserved 3 DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my wife Edla Kaiyo Wimmerth for assisting, encouraging, motivating and being a strong pillar over the years as I was completing this dissertation. It has been quite a tremendous journey, hard work and commitment for me and I would not have completed this enormous work, dissertation without her weighty, profound assistance. 4 ABSTRACT The oil and gas industry, petroleum engineering, exploration, drilling, reservoir and production engineering have taken an enormous toll since the early forties and sixties and it has predominantly reached the peak in the early eighties and nineties. The number of oil and gas companies have been using the vertical drilling approach and successfully managed to pinch the reservoir with productive oil or gas. -

Brazil's Oil Discoveries Bring New

Brazil’s Oil Discoveries Brazil’s discovery of large offshore oil reserves holds the possibility of raising the country’s profile in the international Bring New energy market and bringing an influx of wealth to the country. Safeguard- ing the nation’s economy against the Challenges downside of newfound resource wealth is among its leaders’ concerns. 22 EconSouth First Quarter 2011 While deepwater drilling permits in the United States were Brazil: Oil Production and Consumption, 1995–2012 being withheld because of concerns about safety and the envi- ronment, Brazil is moving at full speed to develop its massive Production deepwater reserves. In fact, Petrobras, the country’s state-run Forecast Consumption oil company, has already committed to investing $224 billion 3 through 2014 in its plan to develop deepwater fields off the country’s coast. day per The Brazilians have much to be optimistic about. The dis- 2 covery of the Tupi oil field in October 2006—the largest oil field barrels found in the Western Hemisphere in 30 years—signified Brazil’s of emergence as a global oil power. During the inaugural extrac- Millions 1 tion from the Tupi super-field, former president Luis Inacio Lula da Silva described the country’s newfound oil riches as a “second independence for Brazil.” (In December 2010, the Tupi 0 field was renamed “Lula.”) Although the oil finds present an 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 enormous opportunity for Brazil, the logistical and political Source: EIA Short-term Energy Outlook, January 2011 challenges involved in developing the fields leave much of the future unmapped, however.