This Is the Greatest Show a Study in Modern Live Experience and Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Philosophy of Communication of Social Media Influencer Marketing

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Summer 8-8-2020 The Banality of the Social: A Philosophy of Communication of Social Media Influencer Marketing Kati Sudnick Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Part of the Digital Humanities Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Sudnick, K. (2020). The Banality of the Social: A Philosophy of Communication of Social Media Influencer Marketing (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1921 This One-year Embargo is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. THE BANALITY OF THE SOCIAL: A PHILOSOPHY OF COMMUNICATION OF SOCIAL MEDIA INFLUENCER MARKETING A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Kati Elizabeth Sudnick August 2020 Copyright by Kati Elizabeth Sudnick 2020 THE BANALITY OF THE SOCIAL: A PHILOSOPHY OF COMMUNICATION OF SOCIAL MEDIA INFLUENCER MARKETING By Kati Elizabeth Sudnick Approved May 1st, 2020 ________________________________ ________________________________ Ronald C. Arnett, Ph.D. Erik Garrett, Ph.D. Professor, Department of Communication & Associate Professor, Department of Rhetorical Studies Communication & Rhetorical Studies (Committee Chair) (Committee -

The Theme Park As "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," the Gatherer and Teller of Stories

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2018 Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories Carissa Baker University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Rhetoric Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Baker, Carissa, "Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5795. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5795 EXPLORING A THREE-DIMENSIONAL NARRATIVE MEDIUM: THE THEME PARK AS “DE SPROOKJESSPROKKELAAR,” THE GATHERER AND TELLER OF STORIES by CARISSA ANN BAKER B.A. Chapman University, 2006 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2018 Major Professor: Rudy McDaniel © 2018 Carissa Ann Baker ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the pervasiveness of storytelling in theme parks and establishes the theme park as a distinct narrative medium. It traces the characteristics of theme park storytelling, how it has changed over time, and what makes the medium unique. -

THE SHAPE of JUSTICE Thumbs up to Free Snacks in Student Affairs

2017 & 2018 ABA Law Student Division Best Newspaper Award-Winner VIRGINIA LAW WEEKLY 70 1948 - 2018 A Look The Malicious Chinchilla: Part the Second.......................................2 Inside: Confirmation Stories: Hugo Black & Supreme Court Secrets..........2 Charlottesville’s Best Donuts, Reviewed by Kids.............................4 Which Fyre Fest Documentary? ......................................................7 Wednesday, 13 February 2019 The Newspaper of the University of Virginia School of Law Since 1948 Volume 71, Number 16 around north grounds THE SHAPE OF JUSTICE Thumbs up to free snacks in Student Affairs. Krasner, Others Keynote PILA Event After dropping a whopping $70 on a Barris- ter’s ticket, ANG can’t even afford groceries. Thanks, Michael Schmid ‘21 Lisa, for saving us all from Staff Editor our own poor decisions. The third annual Shaping Justice conference took place Thumbs up to February 8 and 9 at the Law free snacks in Stu- School, featuring a variety of dent Affairs. After panel discussions, workshops, dropping a whop- and a keynote address by Larry ping $70 on a Barrister’s Krasner, District Attorney for ticket, ANG can’t even af- the City of Philadelphia. The ford groceries. Thanks, event was sponsored by the Lisa, for saving us all from Public Interest Law Associa- our own poor decisions. tion, the Program in Law and Public Service, and the Mor- Thumbs down timer Caplin Public Service to classes that Center. Panel topics included still involve fights gun violence, alternatives to for seating. ANG incarceration, the affordable specifically dropped the housing crisis, and the opioid class in musical chairs for epidemic. anxiety reasons and does The opioid epidemic was a not find this fun. -

2015 Kiddieland

STATE FAIR MEADOWLANDS RIDE LIST - 2015 KIDDIELAND Description Height Requirements Description Height Requirements Banzai 52" MIN Bumble Bee 36" MIN W/O ADULT, 32" MIN W ADULT Bumper Boats - Water 52" MIN W/O ADULT, 32" MIN W ADULT Frog Hopper 56" MAX, 36" MIN-NO ADULTS Bumper Cars 48" MIN TO DRIVE, 42" MIN TO RIDE Speedway 56" MAX, 36" MIN-NO ADULTS Cliffhanger 46" MIN Go Gator 54" MAX, 42" MIN-NO ADULTS Crazy Mouse 55" MIN W/O ADULT, 45" MIN W ADULT Jet Ski/Waverunner 54" MAX, 36" MIN-NO ADULTS Crazy Outback 42" MIN ALONE, 36" MIN W/ADULT Motorcycles 54" MAX, 36" MIN-NO ADULTS Cuckoo Fun House 42" MIN ALONE, 36" MIN W/ADULT Quadrunners 54" MAX, 30" MIN-NO ADULTS Darton Slide TBD VW Cars 54" MAX, 30" MIN-NO ADULTS Disko TBD Double Decker Carousel 52" MIN UABA Enterprise ENTERPRISE 52" MINIMUM Mini Bumper Boats - Water 52" MAX-NO ADULTS Fireball 50" MIN Merry-Go-Round 42" MIN W/O ADULT, NO MIN W ADULT Giant Wheel 54" MIN W/O ADULT, NO MIN W ADULT Rockin' Tug 42" MIN W/O ADULT, 36" MIN W ADULT Gravitron 48" MIN Wacky Worm 42" MIN W/O ADULT, 36" MIN W ADULT Haunted House Dark Ride 42" MIN ALONE, 36" MIN W/ADULT Fire Chief 42" MIN UABA Haunted Mansion Dark Ride 42" MIN ALONE, 36" MIN W/ADULT Family Swinger 42" MIN OUTER SEAT, 36" MIN INNER Haunted Mansion Dark Ride 42" MIN ALONE, 36" MIN W/ADULT Happy Swing 42" MIN OUTER SEAT, 36" MIN INNER Heavy Haulin' Inflate 32" MIN, 76" MAX; 250 LBS MAX Jungle of Fun 42" MIN Himalaya 42” Min. -

Crs4e1forkaytee

Season 4, Episode 1: Unexpected Emotions + How We Spent Our Break Mon, 8/2 • 49:22 Meredith Monday Schwartz 00:10 Hey readers, welcome to the Currently Reading podcast. We are bookish best friends who spend time every week talking about the books that we read recently. And as you know, we don't shy away from having strong opinions. So get ready. Kaytee Cobb 00:25 We are light on the chitchat, heavy on the book talk, and our descriptions will always be spoiler free. We'll discuss our current reads, a bookish deep dive, and then we'll press books into your hands. Meredith Monday Schwartz 00:35 I'm Meredith Monday Schwartz, a mom of four and full time CEO living in Austin, Texas. And talking about books is such a joy in my life. Kaytee Cobb 00:43 And I'm Kaytee Cobb, a homeschooling mom of four living in New Mexico. And I am excited for a new season. This is episode number one of season four and we are so glad you're here. Season Four, Meredith, Meredith Monday Schwartz 00:57 I can't believe it. We're here. Kaytee Cobb 00:59 We're here for season four. Meredith Monday Schwartz 01:01 I know. I know. It sounds like such big girls, right? season four, it's some big girl. Kaytee Cobb 01:06 We're like four year olds now almost like that's crazy. Meredith Monday Schwartz 01:11 I know. And boy, I was not lying when I said the break that we've just had, has reminded me how much I love talking about books. -

Analiza PR Strategije I Kriznog Komuniciranja Na Primjeru Fyre Festivala

Analiza PR strategije i kriznog komuniciranja na primjeru Fyre Festivala Senjak, Antonija Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2020 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, The Faculty of Political Science / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Fakultet političkih znanosti Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:114:101999 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-26 Repository / Repozitorij: FPSZG repository - master's thesis of students of political science and journalism / postgraduate specialist studies / disertations Sveučilište u Zagrebu Fakultet političkih znanosti Diplomski studij novinarstva Antonija Senjak ANALIZA PR STRATEGIJE I KRIZNOG KOMUNICIRANJA NA PRIMJERU FYRE FESTIVALA DIPLOMSKI RAD Zagreb, 2020. Sveučilište u Zagrebu Fakultet političkih znanosti Diplomski studij novinarstva ANALIZA PR STRATEGIJE I KRIZNOG KOMUNICIRANJA NA PRIMJERU FYRE FESTIVALA DIPLOMSKI RAD Mentor: izv. prof.dr.sc. Domagoj Bebić Student: Antonija Senjak Zagreb Rujan, 2020. Izjava o autorstvu Izjavljujem da sam diplomski rad PR kao najmoćniji alat organizacije događaja: Analiza PR strategije i kriznog komuniciranja na primjeru Fyre Festivala, koji sam predala na ocjenu mentoru izv. prof.dr.sc. Domagoju Bebiću, napisala samostalno i da je u potpunosti riječ o mojem autorskom radu. Također, izjavljujem da dotični rad nije objavljen ni korišten u svrhe ispunjenja nastavnih obaveza na ovom ili nekom drugom učilištu te da na temelju njega nisam stekla ECTS bodove. Nadalje, izjavljujem da sam u radu poštivala etička pravila znanstvenog i akademskog rada, a posebno članke 16-19 Etičkoga kodeksa Sveučilišta u Zagrebu. Antonija Senjak ZAHVALE Od srca ponajviše hvala Petri Vulić na bezuvjetnoj podršci i pomoći u kriznim trenucima, kao i Igoru Jurilju koji je uvijek bio spreman ponuditi korisne savjete i usmjeriti me kada bih previše odlutala. -

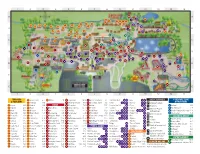

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 a B C D E F G a B C D E F G 1 2 3 4

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 A 44 A 23 37 G 28 35 36 32 31 30 29 14 16 34 33 12 22 24 1 3 4 10 11 2 5 6 13 15 43 21 9 B G B 20 7 8 17 18 3 19 4 24 27 5 6 19 25 20 21 7 C 25 C 22 23 6 12 3 4 2 45 1 2 18 28 3 6 13 16 19 30 1 G 7 17 23 2 15 31 D 2 20 25 27 D 10 29 32 3 G G G 21 G 26 5 1 8 4 12 1 33 G 34 G 1 5 G 24 G 14 1 6 G 9 22 G 13 G G 18 11 11 42 G 5 G G 8 E 4 10 35 E 9 15 G 7 40 41 16 36 14 2 G 4 F 37 F 3 39 17 38 G G 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 TERRACES 21 Group Foods 4-C 16 Willow 7-B 43 Log Flume 10-B 11 Space Scrambler 3-E Cinnamon Roll 9 21 Milk 2 9 GUEST SERVICES X-VENTURE ZONE & PAVILIONS ATTRACTIONS 34 Irontown 9-B 24 Merry-Go-Round 9-D 23 Speedway Junior 9-D Coffee 2 9 19 Nachos 10 25 Drinking Fountain 13 Aspen 6-B 12 Juniper 6-B RIDES 18 Moonraker 7-D 39 Spider 11-F Corn on the Cob 22 Pizza 4 10 Telephone 1 Catapult 2-D 9 Bighorn 4-B Maple 6-C 25 Baby Boats 9-D 36 Musik Express 14-E 22 Terroride 7-E Corndog 10 15 Popcorn 7 Strollers, Wagons 2 Top Eliminator 2-F 15 Birch 6-B 22 Meadow 3-C 12 Bat 4-C 13 OdySea 5-C 31 Tidal Wave 10-D Cotton Candy 7 9 13 Pretzel 4 10 13 21 & Wheelchairs 3 Double Thunder Raceway 3-F 7 Black Hills 3-B 31 Miners Basin 9-A 9 Boomerang 3-E 5 Paratrooper 2-E 10 Tilt-A-Whirl 3-E Dip N Dots5 7 12 18 24 Pulled Pork 22 Gifts & Souvenirs 4 Sky Coaster 4-E 17 Bonneville 5-B 24 Oak 5-C 15 Bulgy the Whale 7-D 28 Puff 9-C 32 Turn of the Century 11-D Floats 9 16 23 Ribs 22 ATM LAGOON A BEACH 10 Bridger 4-B 36 Park Valley 8-A 40 Cliffhanger 11-E 44 Rattlesnake Rapids 10-A 38 Wicked 12-G Frozen 1 11 17 -

Enjoy the Magic of Walt Disney World All Year Long with Celebrations Magazine! Receive 6 Issues for $29.99* (Save More Than 15% Off the Cover Price!) *U.S

Enjoy the magic of Walt Disney World all year long with Celebrations magazine! Receive 6 issues for $29.99* (save more than 15% off the cover price!) *U.S. residents only. To order outside the United States, please visit www.celebrationspress.com. To subscribe to Celebrations magazine, clip or copy the coupon below. Send check or money order for $29.99 to: YES! Celebrations Press Please send me 6 issues of PO Box 584 Celebrations magazine Uwchland, PA 19480 Name Confirmation email address Address City State Zip You can also subscribe online at www.celebrationspress.com. Cover Photography © Mike Billick Issue 44 The Rustic Majesty of the Wilderness Lodge 42 Contents Calendar of Events ............................................................ 8 Disney News ...........................................................................10 MOUSE VIEWS ......................................................... 15 Guide to the Magic by Tim Foster............................................................................16 Darling Daughters: Hidden Mickeys by Steve Barrett ......................................................................18 Diane & Sharon Disney 52 Shutters & Lenses by Tim Devine .........................................................................20 Disney Legends by Jamie Hecker ....................................................................24 Disney Cuisine by Allison Jones ......................................................................26 Disney Touring Tips by Carrie Hurst .......................................................................28 -

THE BOOKSELLERS Page 2

PRESENTING PARTNER MARCH 2020 OPENING FRIDAY, MARCH 13 THE BOOKSELLERS PAGE 2 The world according to Amazon PAGE 4 A rare profile of the most-performed living composer PAGE 5 The millennial decade on screen PAGE 7 For anyone who can still “ look at a book and see a dream.– Variety” “A captivating portrait.” “Timely and essential.” “A compelling reminder of just how – Hollywood Reporter – Los Angeles Times real the news can be.” – POV The Times of Bill Cunningham Afterward This is Not a Movie Opens Friday, February 28 Opens Friday, March 13 Friday, March 27 Page 2 Page 2 Page 2 MELISSA CLARK & SAM SIFTON // DANIEL DALE ERIK LARSON // JERRY SALTZ // TANYA TALAGA PAGE 3 March 6 – 11 @HOTDOCSCINEMA /HOTDOCSCINEMA HOTDOCSCINEMA.CA 506 BLOOR STREET WEST (at Bathurst Street) 2 HOTDOCSCINEMA.CA OPENING at Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema in March MEMBERS BRONZE: $8 TICKETS $13 Silver: $6 SAVE Gold: Free OPENS FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 28 The Times of Bill Cunningham D: Mark Bozek | 2018 | USA | 74 min | PG Get to know iconic street photographer and fashion historian Bill Cunningham in this moving new portrait, including his four decades at The New York Times. Told in Cunningham’s own words from a recently unearthed 1994 interview, the doc chronicles the artist’s fascinating life’s story, including moonlighting as a milliner in France during the Korean War, his unique relationship with First Lady Jackie Kennedy, and his democratic view of fashion and society. Narrated by Sarah Jessica Parker, The Times of Bill Cunningham boasts an incredible archive of photographs chosen from over 3 million previously “Movingly captures unreleased images. -

Beauty and the Beast

BEAUTY AND THE BEAST CHARACTER DESCRIPTIONS: BELLE (Stage Age: 18-30) Belle is the original fairy tale heroine–kind, gentle, and beautiful–but with an important 21st Century twist. She is a strong, intelligent, spirited and independent young woman. Belle is the moral conscience of the story, elevated by her thoughts and deeds. The maturity and depth of her character allow her to see the true beauty and spirit within The Beast, and to love him for it. This role requires a very strong singer who portrays innocence with her singing and speaking voice. MezzoSoprano: Low A-High F THE BEAST (Stage Age: 21-35) The Beast’s tortured soul is evident for all to see. He is paying the ultimate price for a moment of mean-spiritedness, and wishes beyond wishing that he could rectify his mistake. There is anger and menace in The Beast’s appearance and behavior, but increasingly we see his soft and endearing side as he interacts with Belle. It becomes clear that he is a loving, feeling, human being trapped within a hideous creature’s body. This role requires a very strong singer, and the actor must have a strong speaking voice and stage presence. Baritone: A–High F GASTON (Stage Age: 21-35) Gaston is the absolute antithesis of The Beast. Although he is physically handsome, he is shallow, completely self-centered, not very bright, and thrives on attention. However, when his ego is bruised he becomes a very dangerous foe for The Beast, Belle and Maurice. This role requires a strong singer and character actor who moves well. -

Jump-Start Your Career

THE STUDENT NEWSPAPER OF MERCYHURST COLLEGE SINCE 1929 A&E SPORTS Streamline signs Women’s hockey recording ranked 8th a� er deal with tough weekend Sony Records Page 8 Page 11 Vol. 79 No. 7 Mercyhurst College 501 E. 38th St. Erie Pa. 16546 November 2, 2005 THE MERCIAD Jump-start your career “Freshmen and sophomores By Corrie Thearle can establish valuable con- News editor tacts for part-time or summer employment opportunities,” said Many seniors eagerly await the Bob Hvezda, Director of Career day when they receive their fi rst Services. job offer. These students should attend On Thursday, Nov. 3, these dressed in corporate casual students may not have to wait attire. any longer. Underclassmen should not The Offi ce of Career Services is worry if they do not have a holding the 14th annual Career/ complete resume. They should Job Fair in the Mercyhurst Ath- request a buisness card from a letic Center. rep. to forward a resume at a This is the biggest career fair future date. to date with 119 organizations Seniors who are seeking full Katie McAdams/Photo editor participating in the event. time employment should bring Katie McAdams/Photo editor Dr. Thomas Gamble addresses college community in PAC. From American Eagle Outfi t- at least 20 copies of their resume Eric Mead discussed employment with recruiter Jim Voss. ters to the U.S. Coast Guard, on good paper. over 225 campaigning repre- These students should dress only career fair held during the become continually competitive sentatives are looking to hire professionally and be prepared fall in this area. -

Disney Parks, Experiences and Products Reveals Plans for D23 Expo, Aug

DISNEY PARKS, EXPERIENCES AND PRODUCTS REVEALS PLANS FOR D23 EXPO, AUG. 23-25, 2019 Guests will discover an immersive pavilion, entertaining presentations, and all-new merchandise. BURBANK, Calif. (July 17, 2019) – D23 Expo 2019 will be a must for fans of Disney Parks, Experiences and Products. An immersive pavilion will provide an insider’s look at new themed lands, attractions, shows, and more, in addition to a jam-packed schedule of entertaining presentations and a number of exclusive shopping opportunities for every Disney fan. Showcasing an array of new experiences for guests around the world to enjoy for years to come, the Disney Parks “Imagining Tomorrow, Today” pavilion will give fans a unique look at the exciting developments underway at Disney parks around the world. Attendees will see a dedicated space showcasing the historic transformation of Epcot at Walt Disney World Resort. They will also see Tony Stark’s latest plans to recruit guests to join alongside the Avengers in fully immersive areas filled with action and adventure in Hong Kong, Paris, and California. The fan-favorite Hall D23 presentation with Bob Chapek, chairman of Disney Parks, Experiences and Products, will take place Sunday, August 25, at 10:30 a.m. Guests will be treated to more details on much-anticipated attractions, experiences, and transformative storytelling that set Disney apart. During the three-day event, fans can scoop up never-before-seen collectibles across the Disney Parks, Experiences and Products-operated retail shops on the Expo floor: shopDisney.com | Disney Store, Disney DreamStore, Mickey’s of Glendale, and Mickey’s of Glendale Pin Store.