Emergency Planning and the Judiciary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

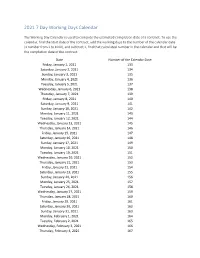

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, January 1, 2021 133 Saturday, January 2, 2021 134 Sunday, January 3, 2021 135 Monday, January 4, 2021 136 Tuesday, January 5, 2021 137 Wednesday, January 6, 2021 138 Thursday, January 7, 2021 139 Friday, January 8, 2021 140 Saturday, January 9, 2021 141 Sunday, January 10, 2021 142 Monday, January 11, 2021 143 Tuesday, January 12, 2021 144 Wednesday, January 13, 2021 145 Thursday, January 14, 2021 146 Friday, January 15, 2021 147 Saturday, January 16, 2021 148 Sunday, January 17, 2021 149 Monday, January 18, 2021 150 Tuesday, January 19, 2021 151 Wednesday, January 20, 2021 152 Thursday, January 21, 2021 153 Friday, January 22, 2021 154 Saturday, January 23, 2021 155 Sunday, January 24, 2021 156 Monday, January 25, 2021 157 Tuesday, January 26, 2021 158 Wednesday, January 27, 2021 159 Thursday, January 28, 2021 160 Friday, January 29, 2021 161 Saturday, January 30, 2021 162 Sunday, January 31, 2021 163 Monday, February 1, 2021 164 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 165 Wednesday, February 3, 2021 166 Thursday, February 4, 2021 167 Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, February 5, 2021 168 Saturday, February 6, 2021 169 Sunday, February -

TM 3.1 Inventory of Affected Businesses

N E W Y O R K M E T R O P O L I T A N T R A N S P O R T A T I O N C O U N C I L D E M O G R A P H I C A N D S O C I O E C O N O M I C F O R E C A S T I N G POST SEPTEMBER 11TH IMPACTS T E C H N I C A L M E M O R A N D U M NO. 3.1 INVENTORY OF AFFECTED BUSINESSES: THEIR CHARACTERISTICS AND AFTERMATH This study is funded by a matching grant from the Federal Highway Administration, under NYSDOT PIN PT 1949911. PRIME CONSULTANT: URBANOMICS 115 5TH AVENUE 3RD FLOOR NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10003 The preparation of this report was financed in part through funds from the Federal Highway Administration and FTA. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The contents of this report reflect the views of the author who is responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do no necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Federal Highway Administration, FTA, nor of the New York Metropolitan Transportation Council. This report does not constitute a standard, specification or regulation. T E C H N I C A L M E M O R A N D U M NO. -

BILLING CYCLE SCHEDULE Department of Procurement, Disbursements & Contract Services 1135 Old Main 600 Lincoln Avenue Charleston, IL 61920

Eastern Illinois University BILLING CYCLE SCHEDULE Department of Procurement, Disbursements & Contract Services 1135 Old Main 600 Lincoln Avenue Charleston, IL 61920 Billing Cycle Beginning Date Billing Cycle Ending Date June 26, 2018 July 25, 2018 Tuesday Wednesday July 26, 2018 August 24, 2018 Thursday Friday August 26, 2018 September 25, 2018 Sunday Tuesday September 26, 2018 October 25, 2018 Wednesday Thursday October 26, 2018 November 26, 2018 Friday Monday November 27, 2018 December 26, 2018 Tuesday Wednesday December 27, 2018 January 25, 2019 Thursday Friday January 26, 2019 February 25, 2019 Saturday Monday February 26, 2019 March 25, 2019 Tuesday Monday March 26, 2019 April 25, 2019 Tuesday Thursday April 26, 2019 May 24, 2019 Friday Friday May 26, 2019 June 25, 2019 Sunday Tuesday June 26, 2019 July 25, 2019 Wednesday Thursday Revised 2/2/18 1 Transactions with a Post Date of: Must be Reviewed Upload to Banner & Approved by: July 1, 2018 – July 6, 2018 July 12, 2018 July 13, 2018 Thursday Friday July 7, 2018 – July 13, 2018 July 19, 2018 July 20, 2018 Thursday Friday July 14, 2018 – July 20, 2018 July 26, 2018 July 27, 2018 Thursday Friday July 21, 2018 – July 27, 2018 August 2, 2018 August 3, 2018 Thursday Friday July 28, 2018 – August 3, 2018 August 9, 2018 August 10, 2018 Thursday Friday August 4, 2018 – August 10, 2018 August 16, 2018 August 17, 2018 Thursday Friday August 11, 2018 – August 17, 2018 August 23, 2018 August 24, 2018 Thursday Friday August 18, 2018 – August 24, 2018 August 30, 2018 August 31, 2018 Thursday -

Pay Week Begin: Saturdays Pay Week End: Fridays Check Date

Pay Week Begin: Pay Week End: Due to UCP no later Check Date: Saturdays Fridays than Monday 7:30am week 1 December 10, 2016 December 16, 2016 December 19, 2016 December 30, 2016 week 2 December 17, 2016 December 23, 2016 December 26, 2016 week 1 December 24, 2016 December 30, 2016 January 2, 2017 January 13, 2017 week 2 December 31, 2016 January 6, 2017 January 9, 2017 week 1 January 7, 2017 January 13, 2017 January 16, 2017 January 27, 2017 week 2 January 14, 2017 January 20, 2017 January 23, 2017 January 21, 2017 January 27, 2017 week 1 January 30, 2017 February 10, 2017 week 2 January 28, 2017 February 3, 2017 February 6, 2017 week 1 February 4, 2017 February 10, 2017 February 13, 2017 February 24, 2017 week 2 February 11, 2017 February 17, 2017 February 20, 2017 March 3, 2017 week 1 February 18, 2017 February 24, 2017 February 27, 2017 ***1 Week Pay Period Transition*** week 1 February 25, 2017 March 3, 2017 March 6, 2017 March 17, 2017 week 2 March 4, 2017 March 10, 2017 March 13, 2017 week 1 March 11, 2017 March 17, 2017 March 20, 2017 March 31, 2017 week 2 March 18, 2017 March 24, 2017 March 27, 2017 week 1 March 25, 2017 March 31, 2017 April 3, 2017 April 14, 2017 week 2 April 1, 2017 April 7, 2017 April 10, 2017 week 1 April 8, 2017 April 14, 2017 April 17, 2017 April 28, 2017 week 2 April 15, 2017 April 21, 2017 April 24, 2017 week 1 April 22, 2017 April 28, 2017 May 1, 2017 May 12, 2017 week 2 April 29, 2017 May 5, 2017 May 8, 2017 week 1 May 6, 2017 May 12, 2017 May 15, 2017 May 26, 2017 week 2 May 13, 2017 May 19, 2017 May -

1 World Trade Center Llc, Et Al

1 WORLD TRADE CENTER LLC, ET AL. - DETERMINATION - 12/03/09 In the Matter of 1 WORLD TRADE CENTER LLC, ET AL. TAT(H)07-34 (CR), ET AL. - DETERMINATION NEW YORK CITY TAX APPEALS TRIBUNAL ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGE DIVISION COMMERCIAL RENT TAX – THE LESSEES' PAYMENTS TO THE PORT AUTHORITY AFTER SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 DID NOT CONSTITUTE BASE RENT PAID FOR TAXABLE PREMISES BECAUSE THE LESSEES NO LONGER HAD THE RIGHT TO OCCUPY SPECIFIC SPACE AFTER THE GOVERNMENT TAKEOVER OF THE WORLD TRADE CENTER SITE ON SEPTEMBER 11, 2001. THUS, THE COMMERCIAL RENT TAX DOES NOT APPLY TO THOSE PAYMENTS. DECEMBER 3, 2009 NEW YORK CITY TAX APPEALS TRIBUNAL ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGE DIVISION : In the Matter of the Petition : DETERMINATION : of : : TAT(H)07-34(CR), et al. 1 World Trade Center LLC, et al. : : Schwartz, A.L.J.: Petitioners, 1 World Trade Center LLC, 2 World Trade Center LLC, 4 World Trade Center LLC and 5 World Trade Center LLC (now known as 3 World Trade Center LLC) (“Petitioners” or the “Silverstein Lessees”) filed Petitions for Hearing with the New York City (“City”) Tax Appeals Tribunal (“Tribunal”) seeking redeterminations of deficiencies of City Commercial Rent Tax (“CRT”) under Chapter 7 of Title 11 of the City Administrative Code (“Code”) for the five tax years beginning June 1, 2001 and ending May 31, 2006 (“Tax Years”). A hearing was held and various documents were admitted into evidence. Petitioners were represented by Elliot Pisem, Esq. and Joseph Lipari, Esq. of Roberts & Holland LLP. The Commissioner of Finance (“Respondent” or “Commissioner”) was represented by Frances J. -

2020-2021 Full Open Schedule FINAL.Xlsx

CITY OF RICHLAND SCHOOL SPEED REDUCTION PROGRAM for Richland School District, Kennewick School District, & Christ the King 2021-22 School Year Richland Elementary Schools Richland Middle Schools Richland High SchoolsKennewick Elem. (Amon Creek) Christ the King School Beacon Schedule ON OFF Days ON OFF Days ON OFF Days ON OFF Days ON OFF Days Normal Start 7:50 8:50 M‐F 6:40 8:05 M‐F 7:30 7:55 M‐F 7:50 8:45 M‐F 7:30 8:30 M‐Th Normal Release 3:10 3:45 M‐Th 2:25 3:00 M‐Th 2:30 2:50 M‐Th 3:10 3:45 M,Tu, Th, F 2:45 3:30 M‐Th Early Release 2:10 2:45 Friday 1:25 2:00 Friday 1:30 1:50 Friday 1:50 2:20 Wednesday 1:30 2:15 Friday Special Early Release 12:25 1:00 See Below 10:55 11:30 See Below 11:00 11:30 See Below 11:20 11:50 See Below 11:15 12:00 See Below First & Last Days First Day September 2, 2021 (early release) August 31, 2021 August 30, 2021 (Freshmen Orient.) September 1, 2021 August 30, 2021 Last Day June 14, 2022 June 14, 2022 June 14, 2022 June 15, 2022 June 10, 2022 Holidays & No School Days Labor Day September 6,2021 September 6,2021 September 6,2021 September 6, 2021 September 6, 2021 Fall Professional Day 1 October 8, 2021 October 8, 2021 October 8, 2021 September 24, 2021 September 20, 2021 Fall Professional Day 2 N/A N/A N/A October 22, 2021 October 8, 2021 Veteran's Day November 11, 2021 November 11, 2021 November 11, 2021 November 11, 2021 November 11, 2021 Fall Conferences N/A N/A N/A November 22, 2021 N/A Thanksgiving Break November 25‐26, 2021 November 25‐26, 2021 November 25‐26, 2021 November 25‐26, 2021 November 22‐26, -

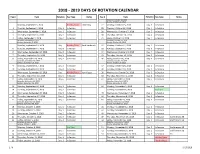

2018 - 2019 Days of Rotation Calendar

2018 - 2019 DAYS OF ROTATION CALENDAR Day # Date Rotation Day Type Notes Day # Date Rotation Day Type Notes Saturday, October 13, 2018 Sunday, October 14, 2018 Monday, September 3, 2018 Holiday/Vaca Labor Day 27 Monday, October 15, 2018 Day 3 In Session 1 Tuesday, September 4, 2018 Day 1 In Session 28 Tuesday, October 16, 2018 Day 4 In Session 2 Wednesday, September 5, 2018 Day 2 In Session 29 Wednesday, October 17, 2018 Day 5 In Session 3 Thursday, September 6, 2018 Day 3 In Session 30 Thursday, October 18, 2018 Day 6 In Session 4 Friday, September 7, 2018 Day 4 In Session 31 Friday, October 19, 2018 Day 1 In Session Saturday, September 8, 2018 Saturday, October 20, 2018 Sunday, September 9, 2018 Sunday, October 21, 2018 Monday, September 10, 2018 Day Holiday/Vaca Rosh Hashanah 32 Monday, October 22, 2018 Day 2 In Session 5 Tuesday, September 11, 2018 Day 5 In Session 33 Tuesday, October 23, 2018 Day 3 In Session 6 Wednesday, September 12, 2018 Day 6 In Session 34 Wednesday, October 24, 2018 Day 4 In Session 7 Thursday, September 13, 2018 Day 1 In Session 35 Thursday, October 25, 2018 Day 5 In Session 8 Friday, September 14, 2018 Day 2 In Session 36 Friday, October 26, 2018 Day 6 In Session Saturday, September 15, 2018 Saturday, October 27, 2018 Sunday, September 16, 2018 Sunday, October 28, 2018 9 Monday, September 17, 2018 Day 3 In Session 37 Monday, October 29, 2018 Day 1 In Session 10 Tuesday, September 18, 2018 Day 4 In Session 38 Tuesday, October 30, 2018 Day 2 In Session Wednesday, September 19, 2018 Day Holiday/Vaca Yom Kippur 39 Wednesday, October 31, 2018 Day 3 In Session 11 Thursday, September 20, 2018 Day 5 In Session 40 Thursday, November 1, 2018 Day 4 In Session 12 Friday, September 21, 2018 Day 6 In Session 41 Friday, November 2, 2018 Day 5 In Session Saturday, September 22, 2018 Saturday, November 3, 2018 Sunday, September 23, 2018 Sunday, November 4, 2018 13 Monday, September 24, 2018 Day 1 In Session 42 Monday, November 5, 2018 Day 6 In Session 14 Tuesday, September 25, 2018 Day 2 In Session Tuesday, November 6, 2018 Prof Dev. -

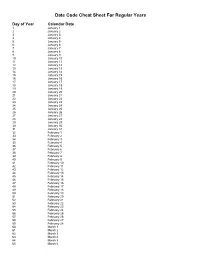

Julian Date Cheat Sheet for Regular Years

Date Code Cheat Sheet For Regular Years Day of Year Calendar Date 1 January 1 2 January 2 3 January 3 4 January 4 5 January 5 6 January 6 7 January 7 8 January 8 9 January 9 10 January 10 11 January 11 12 January 12 13 January 13 14 January 14 15 January 15 16 January 16 17 January 17 18 January 18 19 January 19 20 January 20 21 January 21 22 January 22 23 January 23 24 January 24 25 January 25 26 January 26 27 January 27 28 January 28 29 January 29 30 January 30 31 January 31 32 February 1 33 February 2 34 February 3 35 February 4 36 February 5 37 February 6 38 February 7 39 February 8 40 February 9 41 February 10 42 February 11 43 February 12 44 February 13 45 February 14 46 February 15 47 February 16 48 February 17 49 February 18 50 February 19 51 February 20 52 February 21 53 February 22 54 February 23 55 February 24 56 February 25 57 February 26 58 February 27 59 February 28 60 March 1 61 March 2 62 March 3 63 March 4 64 March 5 65 March 6 66 March 7 67 March 8 68 March 9 69 March 10 70 March 11 71 March 12 72 March 13 73 March 14 74 March 15 75 March 16 76 March 17 77 March 18 78 March 19 79 March 20 80 March 21 81 March 22 82 March 23 83 March 24 84 March 25 85 March 26 86 March 27 87 March 28 88 March 29 89 March 30 90 March 31 91 April 1 92 April 2 93 April 3 94 April 4 95 April 5 96 April 6 97 April 7 98 April 8 99 April 9 100 April 10 101 April 11 102 April 12 103 April 13 104 April 14 105 April 15 106 April 16 107 April 17 108 April 18 109 April 19 110 April 20 111 April 21 112 April 22 113 April 23 114 April 24 115 April -

Memorandum Opinion for the Deputy Counsel to the President*

The President’s Constitutional Authority to Conduct Military Operations Against Terrorists and Nations Supporting Them The President has broad constitutional power to take military action in response to the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001. Congress has acknowledged this inherent executive power in both the War Powers Resolution and the Joint Resolution passed by Congress on Septem- ber 14, 2001. The President has constitutional power not only to retaliate against any person, organization, or state suspected of involvement in terrorist attacks on the United States, but also against foreign states suspected of harboring or supporting such organizations. The President may deploy military force preemptively against terrorist organizations or the states that harbor or support them, whether or not they can be linked to the specific terrorist incidents of September 11. September 25, 2001 MEMORANDUM OPINION FOR THE DEPUTY COUNSEL TO THE PRESIDENT* You have asked for our opinion as to the scope of the President’s authority to take military action in response to the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001. We conclude that the President has broad constitutional power to use military force. Congress has acknowledged this inherent executive power in both the War Powers Resolution, Pub. L. No. 93-148, 87 Stat. 555 (1973), codified at 50 U.S.C. §§ 1541-1548 (the “WPR”), and in the Joint Resolution passed by Congress on September 14, 2001, Pub. L. No. 107-40, 115 Stat. 224 (2001). Further, the President has the constitutional power not only to retaliate against any person, organization, or state suspected of involvement in terrorist attacks on the United States, but also against foreign states suspected of harboring or supporting such organizations. -

2021 Calendar Campaign

One Tail at a Time 2021 Calendar Pets Date Status Date Status Date Status Date Status Date Status Date Status Date Status Date Status Friday, January 1 Not Available Saturday, February 20 Not Available Sunday, April 11 Available Monday, May 31 Not Available Tuesday, July 20 Available Wednesday, September 8 Not Available Thursday, October 28 Available Thursday, December 16 Available Saturday, January 2 Available Sunday, February 21 Available Monday, April 12 Not Available Tuesday, June 1 Available Wednesday, July 21 Not Available Thursday, September 9 Available Friday, October 29 Available Friday, December 17 Available Sunday, January 3 Available Monday, February 22 Available Tuesday, April 13 Available Wednesday, June 2 Available Thursday, July 22 Not Available Friday, September 10 Available Saturday, October 30 Available Saturday, December 18 Not Available Monday, January 4 Available Tuesday, February 23 Available Wednesday, April 14 Available Thursday, June 3 Available Friday, July 23 Available Saturday, September 11 Available Sunday, October 31 Not Available Sunday, December 19 Available Tuesday, January 5 Available Wednesday, February 24 Available Thursday, April 15 Not Available Friday, June 4 Available Saturday, July 24 Available Sunday, September 12 Available Monday, November 1 Available Monday, December 20 Available Wednesday, January 6 Available Thursday, February 25 Available Friday, April 16 Not Available Saturday, June 5 Available Sunday, July 25 Available Monday, September 13 Available Tuesday, November 2 Available Tuesday, -

Due Date Chart 201803281304173331.Xlsx

Special Event Permit Application Due Date Chart for Events from January 1, 2019 - June 30, 2020 If due date lands on a Saturday or Sunday, the due date is moved to the next business day Event Date 30 Calendar days 90 Calendar Days Tuesday, January 01, 2019 Sunday, December 02, 2018 Wednesday, October 03, 2018 Wednesday, January 02, 2019 Monday, December 03, 2018 Thursday, October 04, 2018 Thursday, January 03, 2019 Tuesday, December 04, 2018 Friday, October 05, 2018 Friday, January 04, 2019 Wednesday, December 05, 2018 Saturday, October 06, 2018 Saturday, January 05, 2019 Thursday, December 06, 2018 Sunday, October 07, 2018 Sunday, January 06, 2019 Friday, December 07, 2018 Monday, October 08, 2018 Monday, January 07, 2019 Saturday, December 08, 2018 Tuesday, October 09, 2018 Tuesday, January 08, 2019 Sunday, December 09, 2018 Wednesday, October 10, 2018 Wednesday, January 09, 2019 Monday, December 10, 2018 Thursday, October 11, 2018 Thursday, January 10, 2019 Tuesday, December 11, 2018 Friday, October 12, 2018 Friday, January 11, 2019 Wednesday, December 12, 2018 Saturday, October 13, 2018 Saturday, January 12, 2019 Thursday, December 13, 2018 Sunday, October 14, 2018 Sunday, January 13, 2019 Friday, December 14, 2018 Monday, October 15, 2018 Monday, January 14, 2019 Saturday, December 15, 2018 Tuesday, October 16, 2018 2019 Tuesday, January 15, 2019 Sunday, December 16, 2018 Wednesday, October 17, 2018 Wednesday, January 16, 2019 Monday, December 17, 2018 Thursday, October 18, 2018 Thursday, January 17, 2019 Tuesday, December 18, 2018 -

Negotiating the Mega-Rebuilding Deal at the World Trade Center: Plans for Redevelopment

NEGOTIATING THE MEGA-REBUILDING DEAL AT THE WORLD TRADE CENTER: PLANS FOR REDEVELOPMENT DARA M. MCQUILLAN* & JOHN LIEBER ** Good morning. The current state of Lower Manhattan is the result of multiple years of planning and refinement of designs. Later I will spend a couple of minutes discussing the various buildings that we are constructing. First, to give you a little sense of perspective, Larry Silverstein,1 a quintessential New York developer, first got involved at the World Trade Center and with the Port Authority, owner of the World Trade Center,2 in 1980 when he won a bid to build 7 World Trade Center.3 In 1987, Silverstein completed the seventh tower, just north of the World Trade Center site.4 As Alex mentioned, 7 World Trade Center was not the most attractive building in New York and completely cut off Greenwich Street. Greenwich Street is the main street running through Tribeca and connects one of the most dynamic and interesting neighborhoods in New York to the financial district.5 Greenwich serves as a major link to Wall Street. I used to live in SoHo. I would walk to work at the Twin Towers every morning down Greenwich Street past the Robert DeNiro Film Center, Bazzini‘s Nuts, the parks, and the lofts of movie stars, and all of a sudden I would be in front of a 656-foot brick wall of a building. There were huge wind vortexes which often swept garbage all over the place, you could never get a cab, and it was a very * Vice President of Marketing and Communications for World Trade Center Properties, LLC, and Silverstein Properties, Inc.