Ellery Queen's Poetic Justice Or Expected to Find in This Book but Which Is Absent (A Tale, for Example, by Robert Frost Or T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 2005 Updrafts

Chaparral from the California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving Californiaupdr poets for over 60 yearsaftsVolume 66, No. 3 • April, 2005 President Ted Kooser is Pulitzer Prize Winner James Shuman, PSJ 2005 has been a busy year for Poet Laureate Ted Kooser. On April 7, the Pulitzer commit- First Vice President tee announced that his Delights & Shadows had won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. And, Jeremy Shuman, PSJ later in the week, he accepted appointment to serve a second term as Poet Laureate. Second Vice President While many previous Poets Laureate have also Katharine Wilson, RF Winners of the Pulitzer Prize receive a $10,000 award. Third Vice President been winners of the Pulitzer, not since 1947 has the Pegasus Buchanan, Tw prize been won by the sitting laureate. In that year, A professor of English at the University of Ne- braska-Lincoln, Kooser’s award-winning book, De- Fourth Vice President Robert Lowell won— and at the time the position Eric Donald, Or was known as the Consultant in Poetry to the Li- lights & Shadows, was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2004. Treasurer brary of Congress. It was not until 1986 that the po- Ursula Gibson, Tw sition became known as the Poet Laureate Consult- “I’m thrilled by this,” Kooser said shortly after Recording Secretary ant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. the announcement. “ It’s something every poet dreams Lee Collins, Tw The 89th annual prizes in Journalism, Letters, of. There are so many gifted poets in this country, Corresponding Secretary Drama and Music were announced by Columbia Uni- and so many marvelous collections published each Dorothy Marshall, Tw versity. -

Folktales: Oral Traditions As a Basis for Instruction in Our Schools

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1993 Volume II: Folktales Folktales: Oral Traditions as a Basis for Instruction in our Schools Curriculum Unit 93.02.09 by Soraya R. Potter As a middle school teacher, I see students who come into reading lab hoping that it will be a lot like a library at a university. Everyone has to be quiet and all that they are required to do is read. This is not the case in my class. I view reading as a thinking, speaking, writing and reading workshop where students think and speak about the things they observe, write and read. It is from this angle that I have approached this unit. For me, the unit will primarily serve as an introduction to the new school year. I chose the topic, “Folktales: Oral Traditions as a Basis for Instruction on Our Schools” because I want the unit to serve as an invitation for reluctant readers and speakers to join the lesson freely while also setting the pace for the class during the school year. The unit is designed to help students feel comfortable reading, discussing and writing about selections which they have read. The oral tradition or art of storytelling is one that is almost lost in our society. Every culture which has melted into the great American melting pot has oral traditions which are uniquely their own. These oral traditions are what are known as folklore or folktales. Today, due in part each to commercialization. immigration, and economy, folktales and fairy tales are virtually indistinguishable. -

HARLEM in SHAKESPEARE and SHAKESPEARE in HARLEM: the SONNETS of CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, and GWENDOLYN BROOKS David J

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 5-1-2015 HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS David J. Leitner Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Leitner, David J., "HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS" (2015). Dissertations. Paper 1012. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS by David Leitner B.A., University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana, 1999 M.A., Southern Illinois University Carbondale, 2005 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Department of English in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2015 DISSERTATION APPROVAL HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS By David Leitner A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Approved by: Edward Brunner, Chair Robert Fox Mary Ellen Lamb Novotny Lawrence Ryan Netzley Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April 10, 2015 AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF DAVID LEITNER, for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in ENGLISH, presented on April 10, 2015, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. -

Aftermath : Seven Secrets of Wealth Preservation in the Coming Chaos / James Rickards

ALSO BY JAMES RICKARDS Currency Wars The Death of Money The New Case for Gold The Road to Ruin Portfolio/Penguin An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC penguinrandomhouse.com Copyright © 2019 by James Rickards Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Rickards, James, author. Title: Aftermath : seven secrets of wealth preservation in the coming chaos / James Rickards. Description: New York : Portfolio/Penguin, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019010409 (print) | LCCN 2019012464 (ebook) | ISBN 9780735216969 (ebook) | ISBN 9780735216952 (hardcover) Subjects: LCSH: Investments. | Financial crises. | Finance—Forecasting. | Economic forecasting. Classification: LCC HG4521 (ebook) | LCC HG4521 .R5154 2019 (print) | DDC 332.024—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019010409 Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the author’s alone. While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content. -

The Cinderella Story to Your Class

● ● ● ● ● STUDY GUIDE TO PRODUCTION & ACTIVITIES Introduction Rooted in the belief that the arts are basic to many aspects of education, Pushcart Players is delighted to present “Happily Ever After,” based on the classic tale, “Cinderella.” Pushcart was drawn to this enduring story for many reasons: Its origins are informed by the universal longing to overcome adversity. Certainly it speaks to all of us who have a vision or a dream yet to be fulfilled. And, we never grow tired of its central themes of goodness, generosity and compassion. But perhaps of greatest importance in today’s world of growing up, it provides a pathway for discussion and significant learning opportunities about Bullying Behav - ior – a topic of increasing concern in schools throughout the country. Toward this end we are coupling our presentation of “Happily…” with the book, “Banishing Bullying Behavior” by SuEllen Fried and Blanche Sos - land, PhD, as a resource in the classroom; and have included a section of discussion and activities on Bullying Behavior prepared by Blanche Sosland in this Study Guide. This Study Guide is designed to assist teachers, parents and group leaders in preparing students for the presentation. It also offers suggestions for discussion, art and values tie-in activities following the program. It is our hope that the material suggested in this guide will be tailored to the age and interests of your students and presented in a nurturing and supportive classroom, recreation or home setting. www.pushcartplayers.org•261BloomfieldAvenue,Verona,NJ07044•973-857-1115 TheRootsAgency•www.therootsagency.com•717-227-0060 Happily Ever After - A Cinderella Tale BookandLyricsbyRuthFost MusicbyLarryHochmanandLaurieHochman Summary This production begins with a spoken Prologue set to music that provides an overview of the characters and events that come together to form the Cinderella tale. -

Edwin Arlington Robinson's Interpretation of Tristram

/ EDWIN ARLINGTON ROBINSON’S INTERPRETATION OF TRISTRAM BY MARY EDNA MOLSEED 'r A THESIS Submitted to the Faculty of The Creighton University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of E n g l i s h OMAHA, 1937 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE F O R E W O R D ................................................. i I. AN INTRODUCTION TO ROBINSON .......................... 1 II. THE POSSIBLE ORIGIN OF THE TRISTRAM L E G E N D ..................................................... 13 III. SOME CHARACTERISTICS OF THE TRISTAN STORY BY THOMAS ........................................ 19 IV. LATER VERSIONS OF TRISTRAM .......................... 24 V. ROBINSON'S INTERPRETATION OF TRISTRAM .............33 BIBLIOGRAPHY 44 i FOREWORD ■ The third great epic, Tristram, which was to complete the Arthurian trilogy, so majestically and movingly in terpreted the world-famous medieval romance that the out standing excellences of Robinson's verse, thus far ignored by the large reading public, forced themselves into recognition, and he, after thirty years' patient waiting and unflagging trust in his own genius, at last was greeted with universal applause. Although America in the interval had witnessed an exceptional efflorescence of good poetry, he was hailed, not only as the dean, but as the prince of American bards.* The writer, who considers this statement as valid, bases her thesis on the premise that Robinson did appeal to the modem reader. She aims, first, through a study of the poet in general, to show how he appealed to the public. Because Tristram is classed as a medieval character, she will consider the possible origin of the story. -

Open Shalkey Honors Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH THE CONFESSIONAL POETS: REMOVING THE MASK OF IMPERSONALITY WITH ALL THE SKILLS OF THE MODERNISTS VANESSA SHALKEY Spring 2012 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in English and International Politics with honors in English Reviewed and approved* by the following: John Marsh Assistant Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Lisa Sternlieb English Honors Advisor Honors Advisor Christopher Castiglia Liberal Arts Research Professor of English CALS Senior Scholar in Residence Second Reader *Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. !! ABSTRACT The pioneers of the frontier of new art forms have always made themselves vulnerable to the criticism of the previous generation; however, this criticism often overshadows and undermines the true success of these bold artists. The confessional poets were some of these trailblazers who took American poetry into areas untouched by previous generations and were criticized for breaking with the traditional methods of past poets--especially the modernists. Poets like Robert Lowell and John Berryman used their life events as subject matter for their poetry, which the New Critics thought was bad form. This controversial shift in style won these poets the name “confessional,” a title that many of the poets to whom it refers found disparaging. The label “confessional” gives the impression that these poets did little more than use their poems as diary entries, when in fact they wrote magnificent poetry with the same talent and technical skills that the modernist poets displayed. This thesis is an examination of the confessional poets’ use of effective poetic devices favored by the modernist poets to analyze whether or not the act of removing the mask of impersonality negatively impacted the ability of the confessional poets to develop complex themes and transmute feelings to the reader. -

Rose Gardner Mysteries

JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc. Est. 1994 RIGHTS CATALOG 2019 JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc. 49 W. 45th St., 12th Floor, New York, NY 10036-4603 Phone: +1-917-388-3010 Fax: +1-917-388-2998 Joshua Bilmes, President [email protected] Adriana Funke Karen Bourne International Rights Director Foreign Rights Assistant [email protected] [email protected] Follow us on Twitter: @awfulagent @jabberworld For the latest news, reviews, and updated rights information, visit us at: www.awfulagent.com The information in this catalog is accurate as of [DATE]. Clients, titles, and availability should be confirmed. Table of Contents Table of Contents Author/Section Genre Page # Author/Section Genre Page # Tim Akers ....................... Fantasy..........................................................................22 Ellery Queen ................... Mystery.........................................................................64 Robert Asprin ................. Fantasy..........................................................................68 Brandon Sanderson ........ New York Times Bestseller.......................................51-60 Marie Brennan ............... Fantasy..........................................................................8-9 Jon Sprunk ..................... Fantasy..........................................................................36 Peter V. Brett .................. Fantasy.....................................................................16-17 Michael J. Sullivan ......... Fantasy.....................................................................26-27 -

The Dutch Shoe Mystery

The Dutch Shoe Mystery Ellery Queen To DR. S. J. ESSENSON for his invaluable advice on certain medical matters FOREWORD The Dutch Shoe Mystery (a whimsicality of title which will explain itself in the course of reading) is the third adventure of the questing Queens to be presented to the public. And for the third time I find myself delegated to perform the task of introduction. It seems that my labored articulation as oracle of the previous Ellery Queen novels discouraged neither Ellery’s publisher nor that omnipotent gentleman himself. Ellery avers gravely that this is my reward for engineering the publication of his Actionized memoirs. I suspect from his tone that he meant “reward” to be synonymous with “punishment”! There is little I can say about the Queens, even as a privileged friend, that the reading public does not know or has not guessed from hints dropped here and there in Opus 1 and Opus 2.* Under their real names (one secret they demand be kept) Queen pere and Queen fits were integral, I might even say major, cogs in the wheel of New York City’s police machinery. Particularly during the second and third decades of the century. Their memory flourishes fresh and green among certain ex-offi- cials of the metropolis; it is tangibly preserved in case records at Centre Street and in the crime mementoes housed in their old 87th Street apart- ment, now a private museum maintained by a sentimental few who have excellent reason to be grateful. As for contemporary history, it may be dismissed with this: the entire Queen menage, comprising old Inspector Richard, Ellery, his wife, their infant son and gypsy Djuna, is still immersed in the peace of the Italian hills, to all practical purpose retired from the manhunting scene . -

Ellery Queen Master Detective

Ellery Queen Master Detective Ellery Queen was one of two brainchildren of the team of cousins, Fred Dannay and Manfred B. Lee. Dannay and Lee entered a writing contest, envisioning a stuffed‐shirt author called Ellery Queen who solved mysteries and then wrote about them. Queen relied on his keen powers of observation and deduction, being a Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson rolled into one. But just as Holmes needed his Watson ‐‐ a character with whom the average reader could identify ‐‐ the character Ellery Queen had his father, Inspector Richard Queen, who not only served in that function but also gave Ellery the access he needed to poke his nose into police business. Dannay and Lee chose the pseudonym of Ellery Queen as their (first) writing moniker, for it was only natural ‐‐ since the character Ellery was writing mysteries ‐‐ that their mysteries should be the ones that Ellery Queen wrote. They placed first in the contest, and their first novel was accepted and published by Frederick Stokes. Stokes would go on to release over a dozen "Ellery Queen" publications. At the beginning, "Ellery Queen" the author was marketed as a secret identity. Ellery Queen (actually one of the cousins, usually Dannay) would appear in public masked, as though he were protecting his identity. The buying public ate it up, and so the cousins did it again. By 1932 they had created "Barnaby Ross," whose existence had been foreshadowed by two comments in Queen novels. Barnaby Ross composed four novels about aging actor Drury Lane. After it was revealed that "Barnaby Ross is really Ellery Queen," the novels were reissued bearing the Queen name. -

Intervenor Chesterton Exhibit 2 INDIANA UTILITY REGULATORY COMMISSION Exi1iib Rrs IURC Caus;~~/~I~~

FILED February 11, 2020 Q ffIC T~ified Direct Testimony of Sharon Darnell · · ·· ,.__, .t · Intervenor Chesterton Exhibit 2 INDIANA UTILITY REGULATORY COMMISSION EXi1iIB rrs IURC Caus;~~/~i~~ STATE OF INDIANA INDIANA UTILITY REGULATORY COMMISSl~RC . .-ek.J-kM IN THE MATTER OF THE PETITION OF THE ) INTERVE OR'S CITY OF VALPARAISO INDIANA AND )EXHIBITNO.~,-l-----~~ v ALP ARAISO CITY 'UTILITIES ' FOR )·~DA~:T¥E./ ~~-'---;;;RE:;:;'.PO~Rt=riTE~R o- APPROVAL OF A REGULATORY ORDINANCE ) CAUSE NO. 45306 ESTABLISHING A SERVICE TERRITORY FOR ) THE CITY'S MUNICIPAL SEWER SYSTEM ) PURSUANT TO IND. CODE CH. 8-1.5-6 ) VERIFIED DIRECT TESTIMONY OF SHARON DARNELL I. INTRODUCTION 1 Q. Please state your name and occupation. 2 A. My name is Sharon Darnell. I am semi-retired, working on average one day a week 3 in the office ofR.V. Sutton Excavating, located in Chesterton, Indiana. Formerly, I 4 served as full-time office manager of the company. 5 6 Q. What is your position with the Town of Chesterton ("Town" or "Chesterton")? 7 A. I am the current President of the Chesterton Town Council ("Council"). I served on 8 the Council for sixteen (16) years between 2000 and 2016. Prior to serving on the 9 Council, I was a member of the Town of Chesterton Utility Service Board ("USB") 10 from 1998 to 1999. In my prior four (4) terms with the Council, I served in a variety 11 of positions, including Council President, liaison to the USB, and member of the 12 Chesterton Redevelopment Commission. In November of 2019, I was re-elected to 13 the Council, and took office on January 1, 2020, at which time I was selected by 14 the Council to serve as its President. -

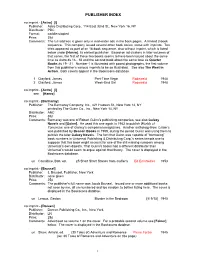

Publisher Index

PUBLISHER INDEX no imprint - [ A s t r o ] [I] Publisher: Astro Distributing Corp., 114 East 32nd St., New York 16, NY Distributor: PDC Format: saddle-stapled Price: 35¢ Comments: The full address is given only in mail-order ads in the back pages. A limited 2-book sequence. This company issued several other book series, some with imprints. Ten titles appeared as part of an 18-book sequence, also without imprint, which is listed below under [Hanro], its earliest publisher. Based on ad clusters in later volumes of that series, the first of these two books seems to have been issued about the same time as Astro #s 16 - 18 and the second book about the same time as Quarter Books #s 19 - 21. Number 1 is illustrated with posed photographs, the first volume from this publisher’s various imprints to be so illustrated. See also The West in Action. Both covers appear in the Bookscans database. 1 Clayford, James Part-Time Virgin Rodewald 1948 2 Clayford, James W eek -End Girl Rodewald 1948 no imprint - [ A s t r o ] [I] see [Hanro] no imprint - [Barmaray] Publisher: The Barmaray Company, Inc., 421 Hudson St., New York 14, NY printed by The Guinn Co., Inc., New York 14, NY Distributor: ANC Price: 35¢ Comments: Barmaray was one of Robert Guinn’s publishing companies; see also Galaxy Novels and [Guinn]. He used this one again in 1963 to publish Worlds of Tomorrow, one of Galaxy’s companion magazines. Another anthology from Collier’ s was published by Beacon Books in 1959, during the period Guinn was using them to publish the later Galaxy Novels.