4. Detectives, Traces, and Repetition in the Exploits of Elaine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Operational Aesthetic in the Performance of Professional Wrestling William P

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 The operational aesthetic in the performance of professional wrestling William P. Lipscomb III Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Lipscomb III, William P., "The operational aesthetic in the performance of professional wrestling" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3825. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3825 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE OPERATIONAL AESTHETIC IN THE PERFORMANCE OF PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Studies by William P. Lipscomb III B.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1990 B.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1991 M.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1993 May 2005 ©Copyright 2005 William P. Lipscomb III All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am so thankful for the love and support of my entire family, especially my mom and dad. Both my parents were gifted educators, and without their wisdom, guidance, and encouragement none of this would have been possible. Special thanks to my brother John for all the positive vibes, and to Joy who was there for me during some very dark days. -

Filmic Bodies As Terministic (Silver) Screens: Embodied Social Anxieties in Videodrome

FILMIC BODIES AS TERMINISTIC (SILVER) SCREENS: EMBODIED SOCIAL ANXIETIES IN VIDEODROME BY DANIEL STEVEN BAGWELL A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Communication May 2014 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Ron Von Burg, Ph.D., Advisor Mary Dalton, Ph.D., Chair R. Jarrod Atchison, Ph.D. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A number of people have contributed to my incredible time at Wake Forest, which I wouldn’t trade for the world. My non-Deac family and friends are too numerous to mention, but nonetheless have my love and thanks for their consistent support. I send a hearty shout-out, appreciative snap, and Roll Tide to every member of the Wake Debate team; working and laughing with you all has been the most fun of my academic career, and I’m a better person for it. My GTA cohort has been a blast to work with and made every class entertaining. I wouldn’t be at Wake without Dr. Louden, for which I’m eternally grateful. No student could survive without Patty and Kimberly, both of whom I suspect might have superpowers. I couldn’t have picked a better committee. RonVon has been an incredibly helpful and patient advisor, whose copious notes were more than welcome (and necessary); Mary Dalton has endured a fair share of my film rants and is the most fun professor that I’ve had the pleasure of knowing; Jarrod is brilliant and is one of the only people with a knowledge of super-violent films that rivals my own. -

Word Search 'Crisis on Infinite Earths'

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! December 6 - 12, 2019 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 V A H W Q A R C F E B M R A L Your Key 2 x 3" ad O R F E I G L F I M O E W L E N A B K N F Y R L E T A T N O To Buying S G Y E V I J I M A Y N E T X and Selling! 2 x 3.5" ad U I H T A N G E L E S G O B E P S Y T O L O N Y W A L F Z A T O B R P E S D A H L E S E R E N S G L Y U S H A N E T B O M X R T E R F H V I K T A F N Z A M O E N N I G L F M Y R I E J Y B L A V P H E L I E T S G F M O Y E V S E Y J C B Z T A R U N R O R E D V I A E A H U V O I L A T T R L O H Z R A A R F Y I M L E A B X I P O M “The L Word: Generation Q” on Showtime Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Bette (Porter) (Jennifer) Beals Revival Place your classified ‘Crisis on Infinite Earths’ Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Shane (McCutcheon) (Katherine) Moennig (Ten Years) Later ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light, Midlothian Mirror and Ellis Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Alice (Pieszecki) (Leisha) Hailey (Los) Angeles 1 x 4" ad (Sarah) Finley (Jacqueline) Toboni Mayoral (Campaign) County Trading Post! brings back past versions of superheroes Deal Merchandise Word Search Micah (Lee) (Leo) Sheng Friendships Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item Brandon Routh stars in The CW’s crossover saga priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 “Crisis on Infinite Earths,” which starts Sunday on “Supergirl.” for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily2 x Light, 3.5" ad Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading Post and online at waxahachietx.com All specials are pre-paid. -

In Jail Are $10 at the Door

A4 + PLUS >> Burt Reynolds dies at 82, See 2A LOCAL FOOTBALL Starbucks to Tigers take get makeover on Buchholz See Below See Page 1B WEEKEND EDITION FRIDAY & SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 7 & 8, 2018 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | $1.00 Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM BOCC BACKS DOWN Friday Old-time music weekend Tax hike nixed/2A Come enjoy a weekend of music, nature and fun along the banks of the Suwannee River at the Stephen Foster CCSO Old Time Music Weekend Photog on September 7- 9 in his- toric White Springs. This three-day event offers par- gets top Weed ticipants in-depth instruc- tion in old-time music tech- niques on the banjo, guitar, nod for vocals, and fiddle for all sale levels. Evening concerts will be poster presented in the Stephen lands Foster Folk Culture Center State Park Auditorium on Friday and Saturday nights at 7 p.m. Instructors will be ‘hoe’ demonstrating their prow- ess on fiddle, banjo, guitar and vocals. Concert tickets in jail are $10 at the door. Workshops instructors will be leading workshops Self-proclaimed prostitute in fiddle, banjo, guitar, and faces sex, drug charges vocals. For more informa- in sting by sheriff’s office. tion call the Events Team at 386- 397-7005 or visit www. By STEVE WILSON floridastateparks.org/park- [email protected] events/Stephen-Foster. An 18-year-old Fort White Anti-bullying fundraiser woman is facing drug and pros- A chicken BBQ will titution charges following a take place, sponsored by mid-day sting earlier this week. Connect Church and The Sarah Williams, who was Power Team, on Friday, born in Tampa Sept. -

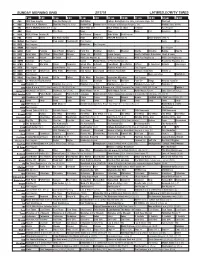

Sunday Morning Grid 2/17/19 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/17/19 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding College Basketball Ohio State at Michigan State. (N) PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey Day Hockey New York Rangers at Pittsburgh Penguins. (N) Hockey: Blues at Wild 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid American Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Paid Program 1 1 FOX Planet Weird Fox News Sunday News PBC Face NASCAR RaceDay (N) 2019 Daytona 500 (N) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Freethought Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Christina Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Grand Canyon Huell’s California Adventures: Huell & Louie 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN Jeffress Win Walk Prince Carpenter Intend Min. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Sensationalism, Cinema and the Popular Press in Mexico and Brazil, 1905-1930 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9mv8w2t2 Author Navitski, Rielle Edmonds Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Sensationalism, Cinema and the Popular Press in Mexico and Brazil, 1905-1930 By Rielle Edmonds Navitski A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kristen Whissel (chair) Professor Natalia Brizuela Professor Mary Ann Doane Professor Mark Sandberg Spring 2013 Sensationalism, Cinema and the Popular Press in Mexico and Brazil, 1905-1930 © 2013 by Rielle Edmonds Navitski Abstract Sensationalism, Cinema and the Popular Press in Mexico and Brazil, 1905-1930 by Rielle Edmonds Navitski Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Kristen Whissel, Chair This dissertation examines the role of new visual reproduction technologies in forging public cultures of sensationalized violence in two rapidly modernizing nations on the periphery of industrial capitalism. I trace parallel developments in the production and reception of silent crime and adventure film in Brazil's First Republic and in revolutionary and post-revolutionary Mexico, at a moment when industrialization and urbanization were reshaping daily experience without eliminating profound social inequalities. Re-evaluating critical frameworks premised on cinema’s relationship to the experience of modernity in the industrialized U.S. and Western Europe, I argue that these early twentieth-century cultures of popular sensationalism signal the degree to which public life in Mexico and Brazil has been conditioned by violence and social exclusion linked to legacies of neo-colonial power. -

The Conspirator of Cordova

/ No. 8. May 2 1 St, 1891. Price, 25 Cents. 1 THE POPULAR SERIES Issued Semi-Monthly. The Conspirator OF Cordova By Sylvanus Cobb, Jr., Author of The Gunmaker of Moscow,” etc. Single Numbers 25 Cents, By Stthscrtplion, (24 Kos.) per Annum, ROBERT BONNER’S SONS, NEW YORK. Entered at the Bast Opice at New York, N, I'., as Second Class ALail Matter. : THE NEW YORK LEDGER. The Illustrated National Family Journal of To-day. A Great Quantity and Variety of Reading. he enlarged size of the Ledger in its new form enables the T publishers to give such an extensive variety of reading matter that every number contains something of interest to every member of the household. While the older members of the household are gathering information from the more weighty editorials on the current topics and international issues of the day, the younger members will find infinite delight and enter- tainment in the purity of the stories. The following is only a partial list of the Eminent and Popular Contributors Amelia E. Barr, Dr. Felix Oswald, Margaret Deland, George F. Parsons, Frances Hodgson Burnett, James McCosh, Robert Louis Stevenson, Rev. Dr. H. M. Field, Anna Katharine Green, Maurice Thompson, Marion Harland, Thomas Dunn English, Col. Thomas W. Knox, Hon. George Bancroft, ‘‘ Josiah Allen’s Wife,” Rev. John R. Paxton, William Henry Bishop, Helen Marshall North, Harold Frederic, Prof. Charles F. Holder, The Marquise Lanza, M. W. Hazeltine, James Russell Lowell, James Parton, Rev. Dr. John Hall« Harriet Prescott SpofPord, Oliver Dyer, Dr. Julia Holmes Smith, Lieut. Frederick Schiwatka Kate M. -

Artbook & Distributed Art Publishers Artbook D.A.P

artbook & distributed art publishers distributed artbook D.A.P. SPRING 2017 CATALOG Matthew Ronay, “Building Excreting Purple Cleft Ovoids” (2014). FromMatthew Ronay, published by Gregory R. Miller & Co. See page 108. FEATURED RELEASES 2 Journals 77 CATALOG EDITOR SPRING HIGHLIGHTS 84 Thomas Evans Art 86 ART DIRECTOR Writings & Group Exhibitions 117 Stacy lakefield Photography 122 IMAGE PRODUCTION Maddie Gilmore Architecture & Design 140 COPY lRITING Janine DeFeo, Thomas Evans, Annabelle Maroney, Kyra Sutton SPECIALTY BOOKS 150 PRINTING Sonic Media Solutions, Inc. Art 152 Group Exhibitions 169 FRONT COVER IMAGE Photography 172 Kazimir Malevich, “Red House” (detail), 1932. From Revolution: Russian Art 1917–1932, published by Royal Academy of Arts. See page 5. Backlist Highlights 178 BACK COVER IMAGE Dorothy Iannone, pages from A CookBook (1969). Index 183 From Dorothy Iannone: A CookBook, published by JRP|Ringier. See page 51. CONTRIBUTORS INCLUDE ■ BARRY BERGDOLL Curator, Department of Architecture and Design, The Museum of Modern Art and Meyer Schapiro Professor of Art History and Archaeology, Department of Art History, Columbia University ■ JOHN MICHAEL DESMOND Professor, College of Art & Design, Louisiana State University ■ CAROLE ANN FABIAN Director, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University ■ JENNIFER GRAY Project Research Assistant, Department of Architecture and Design, The Museum of Modern Art ■ ELIZABETH S. HAWLEY PhD Candidate, The Graduate Center, City University of New York ■ JULIET KINCHIN Curator, Department of Architecture and Design, The Museum of Modern Art ■ NEIL LEVINE Emmet Blakeney Gleason Research Professor of History of Art and Architecture, Modern Architecture, Harvard University ■ ELLEN MOODY Assistant Projects Conservator, The Museum of Modern Art ■ KEN TADASHI OSHIMA Professor, Department of Architecture, University of Washington Frank Lloyd Wright: Unpacking the Archive ■ MICHAEL OSMAN Edited by Barry Bergdoll, Jennifer Gray. -

4.2 on the Political Economy of the Contemporary (Superhero) Blockbuster Series

4.2 On the Political Economy of the Contemporary (Superhero) Blockbuster Series BY FELIX BRINKER A decade and a half into cinema’s second century, Hollywood’s top-of-the- line products—the special effects-heavy, PG-13 (or less) rated, big-budget blockbuster movies that dominate the summer and holiday seasons— attest to the renewed centrality of serialization practices in contemporary film production. At the time of writing, all entries of 2014’s top ten of the highest-grossing films for the American domestic market are serial in one way or another: four are superhero movies (Guardians of the Galaxy, Captain America: The Winter Soldier, X-Men: Days of Future Past, The Amazing Spider-Man 2: Rise of Electro), three are entries in ongoing film series (Transformers: Age of Extinction, Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, 22 Jump Street), one is a franchise reboot (Godzilla), one a live- action “reimagining” of an animated movie (Maleficent), and one a movie spin-off of an existing entertainment franchise (The Lego Movie) (“2014 Domestic”). Sequels, prequels, adaptations, and reboots of established film series seem to enjoy an oft-lamented but indisputable popularity, if box-office grosses are any indication.[1] While original content has not disappeared from theaters, the major studios’ release rosters are Felix Brinker nowadays built around a handful of increasingly expensive, immensely profitable “tentpole” movies that repeat and vary the elements of a preceding source text in order to tell them again, but differently (Balio 25-33; Eco, “Innovation” 167; Kelleter, “Einführung” 27). Furthermore, as part of transmedial entertainment franchises that expand beyond cinema, the films listed above are indicative of contemporary cinema’s repositioning vis-à-vis other media, and they function in conjunction with a variety of related serial texts from other medial contexts rather than on their own—by connecting to superhero comic books, live-action and animated television programming, or digital games, for example. -

October 2019

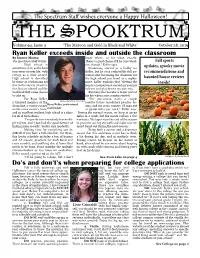

The Spectrum Staff wishes everyone a Happy Halloween! THE SPOOKTRUM Volume 94, Issue 3 “The Maroon and Gold in Black and White” October 28, 2019 Ryan Keller exceeds inside and outside the classroom By Emma Okuma know where, or for what, exactly. The Spectrum Staff Writer There’s a good chance it’ll be Case West- Fall sports High school is ern, though,” Keller says. sometimes seen as the best Drumming started as a hobby for updates, spooky movie four years of your life, with Keller, but he soon realised his full po- recommendations and college as a close second. tential after becoming the drummer for High school is described the high school jazz band as a sopho- haunted house reviews by many as a balancing act more. Keller explains that “Getting the inside! due to the variety of activi- hands-on experience started my journey ties that are offered and the to learn and play drums my own way.” workload that some choose Running also became a major part of to take on. his life when cross country started. For Ryan Keller, “The pre-season starts a couple a talented member of the photo courtesy of Ryan Kellermonths before mandatory practice be- drum line, a varsity runnerRyan Keller, professional gins, and for cross country I’ll max out on the cross country team, multitasker at 55-60 miles per week,” Keller says. and an excellent student, high school is a place “During the normal season, we keep at 40-50 for all of his hobbies. miles in a week, but the meets replace a few “I’m pretty sure everybody has multi- workouts. -

3. Film Serials Between 1910 and 1940

3. Film Serials Between 1910 and 1940 Abstract The third chapter charts the history and development of film serials between the 1910s and the early 1940s. The chapter traces how the opera- tional aesthetic impacted film serial storytelling, as contemporaneous criticism related the serials’ portrayed machines and mechanic death contraptions to their ‘machinic’, that is, continuously propelling narra- tives. These narratives are presentist, as serials establish their episodes as coterminous with the viewer’s own perception of time by reference to previous and upcoming narrative events, and as their narratives expand into multiple spaces as serials connect to newspaper and radio serials and seek to extend their narrative worlds to theater lobbies, local storefronts, and streets. The chapter also delineates the serials’ presentational mode of storytelling. Instead of suturing anecdotes into a seamless whole, serials stress the interstices, self-consciously highlighting their montage character and exploring and exhibiting divergent narrative and cinematographic possibilities of the filmic medium. Keywords: presentism, presentationalism, pressbooks, transmedia storytelling, film exhibition, film serials The operational aesthetic manifests itself visually in specific scenes in individual filmic texts and in corresponding reception experiences: for example, viewers express an interest in process through their reviews or comments, or studios presuppose a similar fascination in their advertising. Such responses surfaced anecdotally—one prominent anecdote appeared, for instance, in the trade-press coverage of a contest issued in relation to one of the most successful early serials. On 13 March 1915, Motion Picture News announced the winner of Thanhouser studio’s scriptwriting contest. The studio had promised to award $10,000 for the best plot suggestions for their ongoing serial The Million Dollar Mystery. -

The Representation of Male Leads in Selected Animated Films: a Visual Analysis

EMERGING VOICES The Representation of Male Leads in Selected Animated Films: A Visual Analysis Sarah Shehattah* 1. Introduction The genre of animation has attracted academic attention due to its growing popularity and success as an entertainment and aesthetic genre. Hapkiewicz (1979) pointed out that animation productions are very popular among children aged between 18 months and two years. Therefore, they could influence Animation films and television cartoons can deliver certain messages to children whether explicitly or implicitly. Such messages can be useful and educational (Baranova, 2014; Padilla-Walker, Coyne, Fraser, & Stockdale, 2013) or harmful and distorted (Coye &Whitehead, 2008; Indhumathi, 2019; Klein & Shiffman, 2006, 2008). Not only children, but also young adults have shown interest in animated films and have been influenced by the messages they contained (Barnes, 2012; Bruce, 2007; Hayes &Tantleff-Dunn, 2010). In fact, animation studios, Disney - - itly depicts power relations and sexuality (Zarranz, 2007, p. 55). Gender portrayal and representations of gender roles in animation production have been investigated by many scholars. Depictions of gender stereotypes in animated films (Coyne, Lindner, Rasmussen, Nelson, & Birkbeck, 2016; Seybold & Rondolino, 2018; Smith, Pieper, Granados, & Choueiti, 2010 ) and in television animated cartoons (e.g., Ahmed & Abdul Wahab, 2014; Coyne, Linder, Rasmussen, Nelson, & Collier, 2014; Leaper, Breed, Hoffman, & Perlman, 2002; Thompson & Zerbinos, 1995, 1997) have received considerable attention from researchers and analysts. Overrepresentation of male characters * Assistant Lecturer in the English Department, Faculty of Foreign Languages and Translation, Misr University for Science & Technology (MUST), Egypt. This paper is derived from a Ph.D. thesis in progress entitled Representation in Selected American Animation Movies: A Pragmatic and Multimodal (Cairo University), supervised by Prof.