39 Corresponding Member, Fort William. with a Map [Plate II.]. THE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Loch Arkaig Land Management Plan Summary

Loch Arkaig Land Management Plan Summary Loch Arkaig Forest flanks the Northern and Southern shores of Loch Arkaig near the hamlets of Clunes and Achnacarry, 15km North of Fort William. The Northern forest blocks are accessed by a minor dead end public road. The Southern blocks are accessed by boat. This area is noted for the fishing, but more so for its link with the training of commandos for World War II missions. The Allt Mhuic area of the forest is well known for its invertebrates such as the Chequered Skipper butterfly. Loch Arkaig LMP was approved on 19/10/2010 and runs for 10 years. What’s important in the new plan: Gradual restoration of native woodland through the continuation of a phased clearfell system Maximisation of available commercial restocking area outwith the PAWS through keeping the upper margin at the altitude it is at present and designing restock coupes to sit comfortably within the landscape Increase butterfly habitat through a network of open space and expansion of native woodland. Enter into discussions with Achnacarry Estate with the aim of creating a strategic timber transport network which is mutually beneficial to the FC and the Estate, with the aim of facilitating the harvesting of timber and native woodland restoration from the Glen Mallie and South Arkaig blocks. The primary objectives for the plan area are: Production of 153,274m3 of timber Restoration of 379 ha of native woodland following the felling of non- native conifer species on PAWS areas To develop access to the commercial crops to enable harvesting operations on the South side of Loch Arkaig To restock 161 ha of commercial productive woodland. -

2-DAY TOUR to EILEAN DONAN CASTLE, LOCH NESS & the WEST

2-DAY TOUR to EILEAN DONAN CASTLE, LOCH NESS & the WEST HIGHLANDS DAY 1 We leave Edinburgh and head west on a motorway that links the capital to Glasgow, the largest city in Scotland and its industrial heartland. From Glasgow, we pass Stirling on the right, the site of the Battle of Bannockburn where, in 1314, a Scottish army under King Robert the Bruce won a crucial victory against the English. Dominating the town is Stirling Castle which sits high on a large volcanic rock. Prominently sited on a hill close to Stirling is the Wallace Monument, our first stop of the day. It is 67 metres high and was built in the 1860’s to commemorate our great freedom fighter, William Wallace, who led an army against the English and defeated them at the Battle of Stirling Bridge in 1297. He was immortalised in the 1995 film ‘Braveheart’. You will have the chance to visit the monument* and the museum inside which has Wallace’s massive sword (1.7 metres long) on display. There are excellent views from the top. At Stirling we head west. Soon we cross over the river Teith and as we do so, on the right, is the very imposing Doune Castle. Next we drive through Callander, and in the area where the Clan MacGregor reigned in the Middle Ages : the clans were extremely powerful at that time and the best known MacGregor was Rob Roy who was born in 1671. At the next village, Tyndrum, the road divides and we head north into a very sparsely populated area. -

Eat – Stay – See – Fort William.Pdf

Eat | Stay | See | Fort William If you are visiting Fort William, here are some options for accommodation, with a range to suit every budget. All accommodations are located within central Fort William, or are just a short journey from the train station. Accommodation List | Fort William Inverlochy Castle Myrtle Bank Guest House 5 Star Country House Hotel. Inverlochy is one 4 Star Guest House in a 1890’s Victorian villa located of Scotland’s finest luxury hotels beside Loch Linhe on the South side of Fort William Address: Torlundy, Fort William PH33 6SN Address: Achintore Rd, Fort William PH33 6RQ Location: 3.6 miles to Tom-na-Faire Station Square Location: 1.1 miles to Tom-na-Faire Station Square Phone: +44 (0)1397 702177 Phone: +44 (0)1397 702034 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Web: www.inverlochycastle.com Web: www.myrtlebankguesthouse.co.uk The Grange Huntingtower Lodge 5 Star Bed and Breakfast set high above Loch Linnhe with 4 Star Bed and Breakfast (Gold Green Tourism Award) superb views to the Ardgour hills Address: Druimarbin, Fort William, PH33 6RP Address: The Grange, Grange Road, Fort William, PH33 6JF Location: 2.7 miles to Tom-na-Faire Station Square Location: 1.3 miles to Tom-na-Faire Station Square Phone: +44 (0)1397 700 079 Phone: +44 (0)1397 705 516 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Web: www.huntingtowerlodge.com Web: www.grangefortwilliam.com When making a reservation, please mention that Wilderness Scotland have recommended them as a place to stay within Fort William. -

Download the Lochaber Fisheries Trust Press Pack

Press Pack Updated May 2014 About Lochaber Fisheries Trust At Lochaber Fisheries Trust we work with river owners, managers, anglers and government agencies to ensure that Lochaber’s freshwaters are protected and managed sustainably. Our aim is to preserve and restore the region’s aquatic environments and ensure that our fish populations persist for many generations to come. Our work covers the following areas; monitoring & research, habitat restoration, fishery management, education, bio-security, interactions with Aquaculture and consultancy. Lochaber is one of the UK’s most stunning and dramatic landscapes and offers anglers a wide choice of fishing from the 'Queen of Scottish salmon rivers' in the shadow of Britain's highest mountain to the icy waters of the country's deepest loch for trout. Lochaber is unique, for fishing with a sense of the untouched and the wild, Lochaber rewards anglers with superb game, course and sea fishing against a backdrop of the most magnificent scenery. Fishing in Lochaber is available to suit every budget, from £7 per day for trout fishing to around £100 for a day’s salmon fishing. • For salmon fishing the River Lochy is unrivalled on the West Coast of Scotland. • The rivers Aline, Inverie, Nevis and Strontian also offer outstanding salmon and sea trout fishing. • Lochs Arkaig and Morar are ideal for ferox and brownies. • Lochs Arienas, Doilet and Dubh-Lochan have plentiful trout. • Loch Arkaig and the River Lochy are perfect for pike anglers. • The coastline of Lochaber is ideal for sea angling. Established in 1996, the Trust is dedicated to improving and raising awareness of fish populations and freshwater habitats in Lochaber. -

Earth As a Whole and Geographic Coordinates

NAME:____________________________________________________________ 1 GO THERE—MYSTERIES OF LOCH NESS, SCOTLAND Use FLY TO and enter Loch Ness, Scotland as the destination. The view will settle in at about 15 miles EYE ALTITUDE, centered about midshore on the northeast coast of the Loch. Note how the cursor (cross-hairs) is labeled Loch Ness, United Kingdom in the VIEW WINDOW. Describe the shape and orientation of Loch Ness based on this view in the box below. Does the shape of the Loch remind you of other bodies of land-based bodies of surface water, and if so what kind? Based on this observation and comparison, describe whether or not the water in the lake is predominantly stationary or rapidly flowing, and give reasons for your arguments in the box below. Without using the ZOOM feature, use the HAND CURSOR and sweep across the lake and along its axis and to determine the average elevation of the lake. Remember that Google Earth® uses an averaging mechanism of regularly spaced coordinates to generate elevations, and that the apparent elevation of the lake is affected by elevations along its shoreline. Record and interpret your findings below. Go to the LAYERS WINDOW, and make sure that the WATER BODIES LAYER is checked in the folder of Geographic Features. In the box below, what do you suppose, based on the other labeled water bodies in the area, the word Loch means? Turn off the WATER BODIES LAYER. The outlines of the WATER BODIES LAYER does not directly overlie the images used as the base for GOOGLE EARTH® in the VIEW WINDOW. -

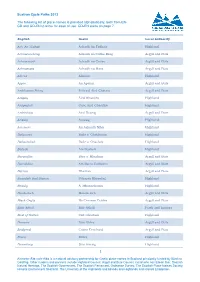

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013 The following list of place-names is provided alphabetically, both from EN- GD and GD-EN to allow for ease of use. GD-EN starts on page 7. English Gaelic Local Authority Ach' An Todhair Achadh An Todhair Highland Achnacreebeag Achadh na Crithe Beag Argyll and Bute Achnacroish Achadh na Croise Argyll and Bute Achnamara Achadh na Mara Argyll and Bute Alness Alanais Highland Appin An Apainn Argyll and Bute Ardchattan Priory Priòraid Àird Chatain Argyll and Bute Ardgay Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardgayhill Cnoc Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardrishaig Àird Driseig Argyll and Bute Arisaig Àrasaig Highland Aviemore An Aghaidh Mhòr Highland Balgowan Baile a' Ghobhainn Highland Ballachulish Baile a' Chaolais Highland Balloch Am Bealach Highland Baravullin Bàrr a' Mhuilinn Argyll and Bute Barcaldine Am Barra Calltainn Argyll and Bute Barran Bharran Argyll and Bute Beasdale Rail Station Stèisean Bhiasdail Highland Beauly A' Mhanachainn Highland Benderloch Meadarloch Argyll and Bute Black Crofts Na Croitean Dubha Argyll and Bute Blair Atholl Blàr Athall Perth and kinross Boat of Garten Coit Ghartain Highland Bonawe Bun Obha Argyll and Bute Bridgend Ceann Drochaid Argyll and Bute Brora Brùra Highland Bunarkaig Bun Airceig Highland 1 Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba is a national advisory partnership for Gaelic place-names in Scotland principally funded by Bòrd na Gaidhlig. Other funders and partners include Highland Council, Argyll and Bute Council, Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, Scottish Natural Heritage, The Scottish Government, The Scottish Parliament, Ordnance Survey, The Scottish Place-Names Society, Historic Environment Scotland, The University of the Highlands and Islands and Highlands and Islands Enterprise. -

Detailed Special Landscape Area Maps, PDF 6.57 MB Download

West Highland & Islands Local Development Plan Plana Leasachaidh Ionadail na Gàidhealtachd an Iar & nan Eilean Detailed Special Landscape Area Maps Mapaichean Mionaideach de Sgìrean le Cruth-tìre Sònraichte West Highland and Islands Local Development Plan Moidart, Morar and Glen Shiel Ardgour Special Landscape Area Loch Shiel Reproduced permissionby Ordnanceof Survey on behalf HMSOof © Crown copyright anddatabase right 2015. Ben Nevis and Glen Coe All rightsAll reserved.Ordnance Surveylicence 100023369.Copyright GetmappingPlc 1:123,500 Special Landscape Area National Scenic Areas Lynn of Lorn Other Special Landscape Area Other Local Development Plan Areas Inninmore Bay and Garbh Shlios West Highland and Islands Local Development Plan Ben Alder, Laggan and Glen Banchor Special Landscape Area Reproduced permissionby Ordnanceof Survey on behalf HMSOof © Crown copyright anddatabase right 2015. All rightsAll reserved.Ordnance Surveylicence 100023369.Copyright GetmappingPlc 1:201,500 Special Landscape Area National Scenic Areas Loch Rannoch and Glen Lyon Other Special Landscape Area BenOther Nevis Local and DevelopmentGlen Coe Plan Areas West Highland and Islands Local Development Plan Ben Wyvis Special Landscape Area Reproduced permissionby Ordnanceof Survey on behalf HMSOof © Crown copyright anddatabase right 2015. All rightsAll reserved.Ordnance Surveylicence 100023369.Copyright GetmappingPlc 1:71,000 Special Landscape Area National Scenic Areas Other Special Landscape Area Other Local Development Plan Areas West Highland and Islands Local -

Scotland's Great Glen Hotel Barge Cruise ~ Fort William to Inverness on Scottish Highlander

800.344.5257 | 910.795.1048 [email protected] PerryGolf.com Scotland's Great Glen Hotel Barge Cruise ~ Fort William to Inverness on Scottish Highlander 6 Nights | 3 Rounds | Parties of 8 or Less PerryGolf is delighted to offer clients an opportunity of cruising the length of Scotland’s magnificent Great Glen onboard the beautiful hotel barge Scottish Highlander, while playing some of Scotland’s finest golf courses. The 8 passenger Scottish Highlander has the atmosphere of a Scottish Country House with subtle use of tartan furnishings and landscape paintings. At 117 feet she is spacious and has every comfort needed for comfortable cruising. On board you will find four en-suite cabins each with a choice of twin or double beds. The experienced crew of four, led by your captain, ensures attention to your every need. Cuisine is traditional Scottish fare, salmon, game, venison and seafood, prepared by your own Master Chef. The open bar is of course well provisioned and in addition to excellent wines is naturally well stocked with a variety of fine Scottish malt whiskies. The itinerary will take you through the Great Glen on the Caledonian Canal which combines three fresh water lochs, Loch Lochy, Loch Oich, and famous Loch Ness, with sections of delightful man made canals to provide marine navigation for craft cutting right across Scotland amidst some spectacular scenery. Golf is included at legendary Royal Dornoch and the dramatic and highly regarded Castle Stuart, which was voted best new golf course worldwide in 2009. In addition you will play Traigh Golf Club (meaning 'beach' in Gaelic) set in one of the most beautiful parts of the West Highlands of Scotland with its stunning views to the Hebridean islands of Eigg and Rum, and the Cuillins of Skye. -

Day 1 Trail Safety Trail Overview Key Contacts

The Great Glen Canoe Trail Is one of the UK’s great canoe adventures. You are advised to paddle the Trail between It requires skill, strength, determination Banavie and Muirtown as the sea access and above all, wisdom on the water. sections at each end involve long and difficult portage. Complete the Trail and join the select paddling few who have enjoyed this truly Enjoy, stay safe and leave no trace. unique wilderness adventure. www.greatglencanoetrail.info Designed and produced by Heehaw Digital | Map Version 3 | Copyright British Waterways Scotland 2011 Trail Safety Contacts Key When planning your trail: When on open water remember: VHF Operation Channels Informal Portage Route Ensure you have the latest Emergency Channel – CH16 Camping Remember to register your paddle trip Orientation weather forecast Read the safety information provided Scottish Canals – CH74 Commercial Panel Wear appropriate clothing Camping by the Caledonian Canal Team Access/Egress Plan where you are staying and book Choose a shore and stick to it Point Handy Phone Numbers Canoe Rack appropriate accommodation if required Stay as a group and look out for Lock Gates each other Canal Office, Inverness – 01463 725500 Bunk House Canal Office, Corpach - 01397 772249 Swing Bridges Be prepared to take shelter should Shopping On the canal remember: the weather change Inverness Harbour - 01463 715715 A Road Parking Look out for and use the Canoe Trail pontoons In the event of an emergency on the water, Met Office – 01392 885680 B Road call 999 and ask for the coastguard Paddle on the right hand side and do not HM Coast Guard, Aberdeen – 01224 592334 Drop Off/Pick Up Railway canoe sail Police, Fort William – 01397 702361 Toilets Great Glen Way Give way to other traffic Always wear a personal Police, Inverness – 01463 715555 Trailblazer Rest River Flow Be alert, and be visible to approaching craft buoyancy aid when on Citylink – 0871 2663333 Watch out for wake caused by larger boats the canal or open water. -

3-Night Scottish Highlands Guided Walking

3-Night Scottish Highlands Guided Walking Tour Style: Guided Walking Destinations: Scottish Highlands & Scotland Trip code: LLBOB-3 2, 5 & 6 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Glen Coe is arguably one of the most celebrated glens in the world with its volcanic origins, and its dramatic landscapes offering breathtaking scenery – magnificent peaks, ridges and stunning seascapes.Easy walks are available, although if you’re up for the challenge we have walks designed to test your stamina and bravery where you can tackle some of Scotland's best mountains. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our Country House • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • 2 days guided walking • Use of our comprehensive Discovery Point www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Discover the dramatic scenery and history of the Scottish Highlands • Opportunity to climb famous summits and bag 'Munros' (mountains over 3,000ft) • Explore the dramatic glens and coastal paths seeking out the best viewpoints. • Join our friendly and knowledgeable guides who will bring this stunning landscape to life. TRIP SUITABILITY This trip is graded Activity Levels 2, 5 and Level 6. Discover the dramatic scenery of the Scottish Highlands on our guided walks. We offer the opportunity to climb famous summits, with many 'Munros' (mountains over 3,000ft) on our itinerary. Alternatively explore the dramatic valleys and coastal paths seeking out the best viewpoints. Join our friendly and knowledgeable guides who will bring this stunning landscape to life. Our experienced guides offer the choice of up to three different walks each day Choose the option which best suits your interests and fitness We provide flexible holidays. -

Journal of a Tour in Scotland in 1819

JOUivi^AL OF A TOUR IN SCOTLAND IN 1819 By ROBERT SOUTHEY With an Introduction and Notes By Professor C. H. Herford, M.A., Litt.D., F.B.A, los. 6d. net See Inside Fiap 315. In 1819 Robert Southey, the Poet Laureate, in company with Telford, the great engineer, made a compre- hensive tour through Scotland, and, being a true bookman, kept a record of the people met and the things seen during their journey. Although no years have passed since then, that Journal has not been published. Yet it has its fresh interest to readers generally and its particular value to social historians and to Scots, for with sincerity and grace Southey wrote down promptly what he saw, and he was no mean observer of his times. JOURNAL OF A TOUR IN SCOTLAND IN 1819 ROBERT SOUTHEY From the. portrait In/ T. PhlUips, R.A. [Frontispiece JOURNAL OF A TOUR IN SCOTLAND IN 1819 BY ROBERT SOUTHEY WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY C. H. HERFORD, M.A., Litt.D., F.B.A. HONORARY PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH LITERATURE IN THK UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER LONDON JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET, W. First Edition 1929 PREFACE The manuscript of this Journal, which is in the library of the Institution of Civil Engineers, was presented to that library in 1885 by the late Sir Robert Rawlinson, K.C.B., who was President of the Institution in 1894-5. It bears a note by him to the effect that he purchased it in Keswick from the Rev. Mr Southey in August 1864. The exhibition of the manuscript on the occasion of the celebration, in June 1928, of the Centenary of the grant of a Royal Charter to the Institution—obtained largely through the instrumentality of Thomas Telford, its first President—drew attention to the interest of the Journal, not only as a contemporary account of the great works which Telford was then carrying out in Scotland, but also as the diary of a shrewd and travelled observer, depicting social and industrial conditions in Scotland in the early years of the nineteenth century. -

Scotland's Road of Romance by Augustus Muir

SCOTLAND‟S ROAD OF ROMANCE TRAVELS IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF PRINCE CHARLIE by AUGUSTUS MUIR WITH 8 ILLUSTRATIONS AND A MAP METHUEN & CO. LTD. LONDON 36 Essex Street W,C, Contents Figure 1 - Doune Castle and the River Tieth ................................................................................ 3 Chapter I. The Beach at Borrodale ................................................................................................. 4 Figure 2 - Borrodale in Arisaig .................................................................................................... 8 Chapter II. Into Moidart ............................................................................................................... 15 Chapter III. The Cave by the Lochside ......................................................................................... 31 Chapter IV. The Road to Dalilea .................................................................................................. 40 Chapter V. By the Shore of Loch Shiel ........................................................................................ 53 Chapter VI. On The Isle of Shona ................................................................................................ 61 Figure 3 - Loch Moidart and Castle Tirrim ................................................................................. 63 Chapter VII. Glenfinnan .............................................................................................................. 68 Figure 4 - Glenfinnan ..............................................................................................................