The Role of the Speaker in Minority Government

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Most Vitriolic Parliament

THE MOST VITRIOLIC PARLIAMENT EVIDENCE OF THE VITRIOLIC NATURE OF THE 43 RD PARLIAMENT AND POTENTIAL CAUSES Nicolas Adams, 321 382 For Master of Arts (Research), June 2016 The University of Melbourne, School of Social and Political Sciences Supervisors: Prof. John Murphy, Dr. Scott Brenton i Abstract It has been suggested that the period of the Gillard government was the most vitriolic in recent political history. This impression has been formed by many commentators and actors, however very little quantitative data exists which either confirms or disproves this theory. Utilising an analysis of standing orders within the House of Representatives it was found that a relatively fair case can be made that the 43rd parliament was more vitriolic than any in the preceding two decades. This period in the data, however, was trumped by the first year of the Abbott government. Along with this conclusion the data showed that the cause of the vitriol during this period could not be narrowed to one specific driver. It can be seen that issues such as the minority government, style of opposition, gender and even to a certain extent the speakership would have all contributed to any mutation of the tone of debate. ii Declaration I declare that this thesis contains only my original work towards my Masters of Arts (Research) except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text to other material used. Equally this thesis is fewer than the maximum word limit as approved by the Research Higher Degrees Committee. iii Acknowledgements I wish to acknowledge my two supervisors, Prof. -

Papers Index

PROOF As at 24 August 2012 Sittings from 5 November 2008 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FOR THE AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY SEVENTH ASSEMBLY 2008–2009–2010–2011–2012 INDEX TO PAPERS Index to Papers Paper MOP Page 2 2003 Canberra Bushfires—McLeod Report and Doogan Coronial Inquiry—Government agreed recommendations—Implementation report, prepared by ACT Bushfire Council, dated June 2009 293 2009-10 Budget surplus—Medial release—ACT Labor, dated 19 September 2008 103 2010 National Multicultural Festival 561 2013 Canberra Centenary—Funding and Tourism—Letter from Tony Windsor MP, Federal Member for New England, dated 24 April 2012 concerning the resolution of the Assembly of 28 March 2012 1900 2013 Canberra Centenary—Funding and Tourism—Letter to the Speaker from Hon Warren Truss MP, Leader of the Nationals, dated 28 May 2012, concerning the resolution of the Assembly of 28 March 2012 2033 2013 Canberra Centenary—Funding and Tourism—Letter to the Speaker from Senator the Hon Jan McLucas, Parliamentary Secretary to the Prime Minister, dated 1 May 2012, concerning the resolution of the Assembly of 28 March 2012 1996 2013 Canberra Centenary—Funding and Tourism—Letter to the Speaker from the Federal Member for Lyne, dated 16 April 2012, relating to the resolution of the Assembly of 28 March 2012 1892 2013 Canberra Centenary—Funding and Tourism—Letter to the Speaker from the Hon Peter Slipper MP, Speaker of the House of Representatives, dated 10 May 2012, concerning the resolution of the Assembly of 28 March 2012 1996 i Index to Papers Paper MOP Page A -

From the Tables *

Robyn Smith is Executive Officer, Office of the Clerk, Legislative Assembly of the Northern Territory From the Tables * Robyn Smith Australian Parliament Former Speaker Peter Slipper tendered his resignation to the Governor-General on 9 October 2012 after months of controversy during which he remained the Speaker but did not preside over proceedings in the House of Representatives. That job fell to Deputy Speaker Anna Burke who was elected to the position on the same evening. Slipper was the second Speaker to resign in 11 months, the first being Harry Jenkins, and the fifth time in the history of the House of Representatives that a sitting Speaker has resigned. The more usual course is for a Speaker to retire once the parliament has been prorogued for a General Election. The House Committee of Privileges and Members’ Interests continues to grapple with a proposed Code of Conduct for Members. This innovation arose from various agreements entered into by the Prime Minister with the Independents during the course of negotiations to form minority government following the 2010 August General Election. The Joint Committee on the Broadcasting of Parliamentary Proceedings spent 12 months in consultation with media representatives, senators, members and parliamentary officers to revise rules governing media coverage of proceedings. This resulted in new media rules being tabled in the Senate and the House of Representatives on 28 November. The rules were last reviewed in 2008. The Usher of the Black Rod and Serjeant-at-Arms have responsibility for administering the rules which seek to balance the media’s right to report parliamentary proceedings whilst respecting the privacy of senators and members and allowing them, other building occupants and visitors to Parliament House to go about their business. -

Theparliamentarian

TheParliamentarian Journal of the Parliaments of the Commonwealth 2015 | Issue Three XCVI | Price £13 Elections and Voting Reform PLUS Commonwealth Combatting Looking ahead to Millenium Development Electoral Networks by Terrorism in Nigeria CHOGM 2015 in Malta Goals Update: The fight the Commonwealth against TB Secretary-General PAGE 150 PAGE 200 PAGE 204 PAGE 206 The Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) Shop CPA business card holders CPA ties CPA souvenirs are available for sale to Members and officials of CPA cufflinks Commonwealth Parliaments and Legislatures by CPA silver-plated contacting the photoframe CPA Secretariat by email: [email protected] or by post: CPA Secretariat, Suite 700, 7 Millbank, London SW1P 3JA, United Kingdom. STATEMENT OF PURPOSE The Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) exists to connect, develop, promote and support Parliamentarians and their staff to identify benchmarks of good governance and implement the enduring values of the Commonwealth. Calendar of Forthcoming Events Confirmed at 24 August 2015 2015 September 2-5 September CPA and State University of New York (SUNY) Workshop for Constituency Development Funds – London, UK 9-12 September Asia Regional Association of Public Accounts Committees (ARAPAC) Annual Meeting - Kathmandu, Nepal 14-16 September Annual Forum of the CTO/ICTs and The Parliamentarian - Nairobi, Kenya 28 Sept to 3 October West Africa Association of Public Accounts Committees (WAAPAC) Annual Meeting and Community of Clerks Training - Lomé, Togo 30 Sept to 5 October CPA International -

Faculty of Law

FACULTY OF LAW GEORGE WILLIAMS AO DEAN ANTHONY MASON PROFESSOR SCIENTIA PROFESSOR 4 April 2017 Committee Secretary Select Committee on a National Integrity Commission PO Box 6100 Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Secretary Thank you for the opportunity to make a submission to this inquiry into the Establishment of a National Integrity Commission. We do so in a personal capacity. Australia’s anti-corruption system needs reform. The diffusion of responsibilities across multiple agencies risks underreporting of corrupt conduct, while gaps in the regime mean that the system fails to hold people accountable. As a result, community and public confidence in Australia’s institutions is eroded. The solution is a national whole- of-government anti-corruption body encompassing the public sector with the power to apply a uniform standard of corrupt conduct. The existing system: the multi-agency approach Australia’s existing anti-corruption and integrity system divides responsibilities across several Commonwealth agencies. Characterised as the ‘multi-agency’ approach, this framework empowers different institutions with ‘specific responsibilities for tackling corruption in different levels of government, and in relation to specific types of corruption’.1 It is premised on the fact that ‘the risks of corruption in the Australian Public Service vary according to each agency’s operating environment’, and that anti- corruption efforts will be best realised when each agency ‘consider[s] their own risk profile[] and take[s] reasonable measures to mitigate risks’.2 1 Attorney-General's Department, The Commonwealth's Approach to Anti-Corruption (Discussion Paper, 2012) 4. 2 Australian Public Service Commission, State of the Service Report 2012–2013 (2013) 71. -

Submission to the Senate Select Committee Into the Political Influence of Donations

Submission to the Senate Select Committee into the Political Influence of Donations Dr Charles Livingstone & Ms Maggie Johnson Gambling and Social Determinants Unit School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine Monash University 9 October 2017 1 Introduction Gambling in Australia is a prime cause of avoidable harm, with the harms of gambling estimated to be of the same order of magnitude as alcohol, and far higher than that associated with illicit drug consumption. (Browne et al, 2016; 2017). The gambling industry is a major donor to Australian political parties and politicians and appears to hold considerable cachet with many political actors, at both federal and state level. In this, it appears to be similar to other industries that produce harmful products, such as alcohol and tobacco. Its purpose in donating to political parties and politicians is similar; it seeks to deny the harmful effects of its products, delay or wind back reform, avoid effective regulation, and continue to extract profits for as long as possible. a) The level of influence that political donations exert over the public policy decisions of political parties, Members of Parliament and Government administration; The Australian gambling industry has utilised political donations as a mechanism to exert considerable influence over relevant public policy. This has been facilitated by the current donations regime, which has numerous flaws from the perspective of transparency and support for policy that acts in the genuine interest of the public. The industry is both significantly resourced and politically organised, and has actively sought opportunities for political engagement via donations to politicians and political parties. -

Inside the Canberra Press Gallery: Life in the Wedding Cake of Old

INSIDE the CANBERRA PRESS GALLERY Life in the Wedding Cake of Old Parliament House INSIDE the CANBERRA PRESS GALLERY Life in the Wedding Cake of Old Parliament House Rob Chalmers Edited by Sam Vincent and John Wanna THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Chalmers, Rob, 1929-2011 Title: Inside the Canberra press gallery : life in the wedding cake of Old Parliament House / Rob Chalmers ; edited by Sam Vincent and John Wanna. ISBN: 9781921862366 (pbk.) 9781921862373 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Australia. Parliament--Reporters and Government and the press--Australia. Journalism--Political aspects-- Press and politics--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Vincent, Sam. Wanna, John. Dewey Number: 070.4493240994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Back cover image courtesy of Heide Smith Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgments . vii Foreword . ix Preface . xi 1 . Youth . 1 2 . A Journo in Sydney . 9 3 . Inside the Canberra Press Gallery . 17 4 . Menzies: The giant of Australian politics . 35 5 . Ming’s Men . 53 6 . Parliament Disgraced by its Members . 71 7 . Booze, Sex and God . -

(2012) the Slipper Conspiracy – Sedition Or Contempt?

Owen Walsh (2012) The Slipper conspiracy – sedition or contempt? This paper was prompted by community reactions to the alleged political conspiracy against the Speaker of House of Representatives, with some in the community raising the prospect of treason or sedition being committed. The paper details the background to and nature of the conspiracy claims, considers the applicability of sedition and treason offences and alternative legal responses, including exercise of parliamentary powers to punish contempt. It concludes that, in the circumstances, recourse to parliamentary contempt power is as equally problematic and dangerous as the suggested recourse to sedition laws.1 Background and political context In April 2012, Mr James Ashby, a staff member of the Speaker of the House of Representatives commenced civil proceedings against the Speaker and the Commonwealth of Australia, alleging sexual harassment by the Speaker and claiming damages for breach of his employment contract with the Commonwealth.2 The claims made included allegations that the Speaker, the Hon Peter Slipper MP, had fraudulently misused travel vouchers. Slipper subsequently announced his intention to step aside from the Speakership. That is, that he would not take the Speaker's Chair and not enter the chamber of the House, pending the outcome of an investigation into allegations of travel-related fraud. The Deputy Speaker, Labor MP Anna Burke, assumed the duties of Speaker in the Chamber. The prevailing political climate and the circumstances of the Speaker’s appointment, together with the salacious nature of the sexual harassment allegations, fuelled the controversy. Slipper, a Liberal National Party [LNP] member for the Queensland electorate of Fisher, had been elected Speaker in November 2011 on the nomination and votes of the Labor Commonwealth Government and despite opposition from his coalition colleagues. -

PM Will Rue Yet Another Bad Call

PM will rue yet another bad call BY:DENNIS SHANAHAN, POLITICAL EDITOR From: The Australian October 10, 2012 12:00AM PETER Slipper has demonstrated better political judgment in apologising for his actions and resigning as Speaker than Julia Gillard has in digging in to defend him. Only hours after the Prime Minister voted to keep him in the chair and launched a ferocious personal attack on Tony Abbott for misogyny, she sat as a stony witness to Slipper's tearful resignation for the same failing and degradation of women. Rather than taking the initiative and leaving Slipper to fall on his sword, Labor went to full- blooded battle and tried to make political gains in its obsessive war on the Liberal leader. When it was obvious to everyone that the new trove of degrading sexual texts unearthed in court meant Slipper's career was over and that Labor should take the lead in his removal to justify its high moral stance on sexism and denigration of women, the Prime Minister dug in. Labor's defence of Slipper involved an offensive launched against Abbott as being as bad as the Speaker when it came to attitudes towards women. Although there was no moral equivalence with Slipper's sex texts to his adviser and jokes about jars of "pickled c . ts" and an ignorant bitch of an MP, Anthony Albanese and Gillard threw the allegations against Abbott to deflect the Coalition's efforts to remove the Speaker. Blind to public concern and outrage, Labor tried to hold on to Slipper to back its brilliant coup last year in getting him to defect and keep that precious one-seat buffer it lost when Tasmanian independent Andrew Wilkie dropped his guaranteed support after being dudded on a deal over limiting poker machines. -

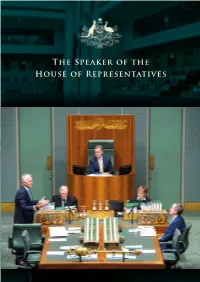

The Speaker of the House of Representatives the Speaker of the House of Representatives the Speaker of the House of Representatives

The Speaker of the House of Representatives of the House of The Speaker The Speaker of the House of Representatives The Speaker of the House of Representatives 1 © Commonwealth of Australia 2016 ISBN 978-1-74366-502-2 Printed version Prepared by the Department of the House of Representatives Photos of certain former Speakers courtesy of The National Library of Australia and Auspic/DPS (David Foote) 2 THE SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES The Speaker of the House of Representatives is the Honourable Tony Smith MP. He was elected as Speaker on 10 August 2015. Mr Smith, the Federal Member for Casey, was first elected in 2001, and re-elected at each subsequent election. The Victorian electoral division of Casey covers an area of approximately 2,500 square kilometres, extending from the outer eastern suburbs of Melbourne into the Yarra Valley and Dandenong Ranges. Industries in the electorate include market gardens, orchards, nurseries, flower farms, vineyards, forestry and timber, tourism, light manufacturing and engineering. The Speaker has previously served as the Parliamentary Secretary to the Prime Minister from 30 January 2007 to 3 December 2007, and in a range of Shadow Ministerial positions in the 42nd and 43rd parliaments. Mr Smith has also served on numerous parliamentary committees and was most recently Chair of the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters in the 44th Parliament. The Speaker studied a Bachelor of Arts (Hons) and Bachelor of Commerce at the University of Melbourne. The Speaker is married to Pam and has two sons, Thomas and Angus. THE OFFICE OF SPEAKER The Speakership is the most important office in the House of Representatives and the Speaker, the principal office holder. -

Web Application Name Organisation Name Address1 Address2 Address3 Address4 Country Organisation Type Name Subscription Type Admi

WEB_APPLICATION_NAME ORGANISATION_NAME ADDRESS1 ADDRESS2 ADDRESS3 ADDRESS4 COUNTRY ORGANISATION_TYPE_NAMESUBSCRIPTION_TYPE ADMINISTRATOR_NAME IELTSTRF Aleksander Moisiu University of Durres "Currila" street Quarter no 1 Durres Albania IELTS RO TYPE 電子加發 Pamela Qendro IELTSTRF IAE Business School Mariano Acosta s/n y Ruta 8 - Pilar - Buenos Aires Argentina IELTS RO TYPE 電子加發 Ignacio Schnitzler IELTSTRF American University of Armenia - Office of Admissions 40 Baghramyan Ave Yerevan 0019 Armenia IELTS RO TYPE 電子加發 Arina Zohrabian IELTSTRF ACT Nursing and Midwifery Board Suite 1, Scala House 11 Torrens Street Braddon ACT 2611 Australia IELTS RO TYPE 電子加發 Adam Young IELTSTRF AHPRA - Canberra Unit 1 Scala House 11 Torrens Street Braddon ACT 2612 Australia IELTS RO TYPE 電子加發 Taryn Robson IELTSTRF AHPRA - Melbourne Level 8, 111 Bourke Street Melbourne Victoria 3001 Australia IELTS RO TYPE 電子加發 Tony Butcher IELTSTRF AHPRA - Perth GPO Box 9958 Perth WA 6001 Australia IELTS RO TYPE 電子加發 Kim Firth IELTSTRF AHPRA - Tasmania Level 12, AMP Building Corner Elizabeth & Collins St Hobart, Tasmania Australia IELTS RO TYPE 電子加發 Jayne Convey IELTSTRF AMI Education Level 4 303 Collins Street Melbourne 3000 Australia IELTS RO TYPE 電子加發 Tanishq Oberoi IELTSTRF AUSAID (Scholarships) 255 London Circuit Canberra ACT 2601 Australia IELTS RO TYPE 電子加發 Sophie Jin IELTSTRF AUSAID Nauru Australian High Commission Nauru C/O Locked Bag 40 Kingston, ACT, 2604 Australia IELTS RO TYPE 電子加發 Gay Uera IELTSTRF About Training Australia Level 2/10, Gasoline Way Craigieburn, Victoria -

Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Twenty-Four

Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Twenty-four Proceedings of the Twenty-fourth Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society Traders Hotel Brisbane, 159 Roma Street, Hobart — August 2012 © Copyright 2014 by The Samuel Griffith Society. All rights reserved. Contents Introduction Julian Leeser The Fourth Sir Harry Gibbs Memorial Oration Senator the Honourable George Brandis In Defence of Freedom of Speech Chapter One The Honourable Ian Callinan Defamation, Privacy, the Finkelstein Report and the Regulation of the Media Chapter Two Michael Sexton Flights of Fancy: The Implied Freedom of Political Communication 20 Years On Chapter Three The Honourable Justice J. D. Heydon Sir Samuel Griffith and the Making of the Australian Constitution Chapter Four The Honourable Christian Porter Federal-State Relations and the Changing Economy Chapter Five The Honourable Richard Court A Federalist Agenda for Coast to Coast Liberal (or Labor) Governments Chapter Six Keith Kendall The Case for a State Income Tax Chapter Seven Josephine Kelly The Constitutionality of the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act i Chapter Eight The Honourable Gary Johns Native Title 20 Years On: Beyond the Hyperbole Chapter Nine Lorraine Finlay Indigenous Recognition – Some Issues Chapter Ten J. B. Paul Speaker of the House Contributors ii Introduction Julian Leeser The 24th Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society was held in Brisbane during the weekend of 17-19 August 2012. It marked the 20th anniversary of the Society’s birth. 1992 was undoubtedly a momentous year in Australia’s constitutional history. On 2 January 1992 the perspicacious John and Nancy Stone decided to incorporate the Samuel Griffith Society thirteen days after Paul Keating was appointed Prime Minister.