Nesting Biology of the Long-Tailed Manakin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

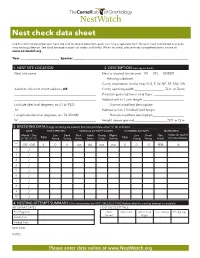

Nest Check Data Sheet

Nest check data sheet Use this form to describe your nest site and to record data from each visit. Use a separate form for each nest monitored and each new nesting attempt. See back for explanations of codes and fields. When finished, please enter completed forms online at: www.nestwatch.org. Year _________________________ Species ______________________________________________________________________________ 1. NEST SITE LOCATION 2. DESCRIPTION (see key on back) Nest site name Nest is located (circle one) IN ON UNDER __________________________________________________ Nesting substrate _______________________________ Cavity orientation (circle one) N, S, E, W, NE, SE, NW, SW Address: Nearest street address OR Cavity opening width __________________ ❏ in. or ❏ cm __________________________________________________ Predator guard ❏ None or ❏ Type: __________________ __________________________________________________ Habitat within 1 arm length _________________________ Latitude (decimal degrees; ex 47.67932) Human modified description ___________________ N _______________________________________________ Habitat within 1 football field length _________________ Longitude (decimal degrees; ex -76.45448) Human modified description ___________________ W _______________________________________________ Height above ground ____________________❏ ft. or ❏ m 3. BREEDING DATA If eggs or young are present but not countable, enter “u” for unknown. DATE HOST SPECIES STATUS & ACTIVITY CODES COWBIRD ACTIVITY MORE INFO Month / Day Live Dead Nest Adult Young -

A Comprehensive Multilocus Phylogeny of the Neotropical Cotingas

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 81 (2014) 120–136 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A comprehensive multilocus phylogeny of the Neotropical cotingas (Cotingidae, Aves) with a comparative evolutionary analysis of breeding system and plumage dimorphism and a revised phylogenetic classification ⇑ Jacob S. Berv 1, Richard O. Prum Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, P.O. Box 208105, New Haven, CT 06520, USA article info abstract Article history: The Neotropical cotingas (Cotingidae: Aves) are a group of passerine birds that are characterized by Received 18 April 2014 extreme diversity in morphology, ecology, breeding system, and behavior. Here, we present a compre- Revised 24 July 2014 hensive phylogeny of the Neotropical cotingas based on six nuclear and mitochondrial loci (7500 bp) Accepted 6 September 2014 for a sample of 61 cotinga species in all 25 genera, and 22 species of suboscine outgroups. Our taxon sam- Available online 16 September 2014 ple more than doubles the number of cotinga species studied in previous analyses, and allows us to test the monophyly of the cotingas as well as their intrageneric relationships with high resolution. We ana- Keywords: lyze our genetic data using a Bayesian species tree method, and concatenated Bayesian and maximum Phylogenetics likelihood methods, and present a highly supported phylogenetic hypothesis. We confirm the monophyly Bayesian inference Species-tree of the cotingas, and present the first phylogenetic evidence for the relationships of Phibalura flavirostris as Sexual selection the sister group to Ampelion and Doliornis, and the paraphyly of Lipaugus with respect to Tijuca. -

Golden-Headed Manakin)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour Pipra erythrocephala (Golden-headed Manakin) Family: Pipridae (Manakins) Order: Passeriformes (Perching Birds) Class: Aves (Birds) Fig. 1. Male golden-headed manakin, Pipra erythrocephala. [http://www.flickr.com/photos/ucumari/388365459/in/photostream, downloaded November 3, 2011] TRAITS. It is a small passerine bird whose length can range between 8 to 10 cm and weighs between 12 to 14g (Bouglouan, 2009). The males of the species have a yellow-orange head which includes the crown, cheek and upper nape. There is a slight red border at the base of the head as seen in figure 1.The rest of their body is covered in black plumage. Their beaks are slight yellow and their feet are pink-brown. The iris of the eye is white. The females and the juvenile males are olive green in colour with grey irises as seen in figures 2 and 3. ECOLOGY. The golden-headed manakin can be found in moist forest habitats and open second growth woodlands (The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 2011). Their altitudinal range is 0 to 2000 metres. Their geographic range is Central and South America and Trinidad and Tobago (The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 2011). UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour SOCIAL ORGANIZATION. There is a highly complex social organisation amongst the males of the species. They gather in groups of up to 12 birds to put on displays in a communal lek (Lynx, 2011). A lek is an area where they display courtship behaviour. -

Abstract Book

Welcome to the Ornithological Congress of the Americas! Puerto Iguazú, Misiones, Argentina, from 8–11 August, 2017 Puerto Iguazú is located in the heart of the interior Atlantic Forest and is the portal to the Iguazú Falls, one of the world’s Seven Natural Wonders and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The area surrounding Puerto Iguazú, the province of Misiones and neighboring regions of Paraguay and Brazil offers many scenic attractions and natural areas such as Iguazú National Park, and provides unique opportunities for birdwatching. Over 500 species have been recorded, including many Atlantic Forest endemics like the Blue Manakin (Chiroxiphia caudata), the emblem of our congress. This is the first meeting collaboratively organized by the Association of Field Ornithologists, Sociedade Brasileira de Ornitologia and Aves Argentinas, and promises to be an outstanding professional experience for both students and researchers. The congress will feature workshops, symposia, over 400 scientific presentations, 7 internationally renowned plenary speakers, and a celebration of 100 years of Aves Argentinas! Enjoy the book of abstracts! ORGANIZING COMMITTEE CHAIR: Valentina Ferretti, Instituto de Ecología, Genética y Evolución de Buenos Aires (IEGEBA- CONICET) and Association of Field Ornithologists (AFO) Andrés Bosso, Administración de Parques Nacionales (Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable) Reed Bowman, Archbold Biological Station and Association of Field Ornithologists (AFO) Gustavo Sebastián Cabanne, División Ornitología, Museo Argentino -

Nest Architecture and Placement of Three Manakin Species in Lowland Ecuador José R

Cotinga29-080304.qxp 3/4/2008 10:42 AM Page 57 Cotinga 29 Nest architecture and placement of three manakin species in lowland Ecuador José R. Hidalgo, Thomas B. Ryder, Wendy P. Tori, Renata Durães, John G. Blake and Bette A. Loiselle Received 14 July 2007; final revision accepted 24 September 2007 Cotinga 29 (2008): 57–61 El conocimiento sobre los hábitat de reproducción de muchas especies tropicales es limitado. En particular, la biología de anidación de varias especies de la familia Pipridae, conocida por sus carac- terísticos despliegues de machos en asambleas de cortejo, es poco conocida. Aquí proporcionamos descripciones y comparamos la arquitectura de nidos y lugares de anidación utilizados por tres especies de saltarines: Saltarín Cola de Alambre Pipra filicauda,Saltarín Coroniblanco P. pipra y Saltarín Coroniazul Lepidothrix coronata,presentes en la Amazonia baja del Ecuador.Encontramos 76 nidos de P. filicauda,13 nidos de P. pipra y 41 nidos de L. coronata.Los resultados indican que P. filicauda y L. coronata usan hábitat similares para anidar (flancos o crestas de quebradas pequeñas), mientras que P. pipra tiende a anidar en sitios relativamente abiertos rodeados por sotobosque más denso. Las tres especies construyen nidos pequeños, poco profundos, los cuales, a pesar de ser similares, son distinguibles debido a sus componentes estructurales y características de ubicación. Este estudio contribuye a nuestro conocimiento sobre los hábitos de anidación de la avifauna tropical. Manakins (Pipridae) are widespread throughout Guiana16,and L. coronata from Central America13). warm and humid regions of Central and South There is no published information, however, on the America4,10,14,but reach their greatest diversity in nesting biology of these three species in Ecuador lowland Amazonia where up to eight species may and, due to observed geographic variation, such occur in sympatry1,4,14.Manakins are small, data are valuable. -

Vocal Repertoire of the Long-Tailed Manakin and Its Relation to Male-Male Cooperation’

THE CONDORDEC-61 A JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY LIBRARY Volume 95 Number 4 November 1993 The Condor 95:769-78 I 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1993 VOCAL REPERTOIRE OF THE LONG-TAILED MANAKIN AND ITS RELATION TO MALE-MALE COOPERATION’ JILL M. TRAINER Department of Biology, Universityof Northern Iowa, Cedar Falls, IA 50614 DAVID B. MCDONALD ArchboldBiological Station, P.O. Box 2057, Lake Placid, FL 33852 Abstract. We examined the vocal repertoire of lek-mating Long-tailed Manakins (Chi- roxiphia linearis, Pipridae) in Monteverde, Costa Rica. Males in this genusare unusualin performing a cooperativecourtship display, including duet songsand coordinateddual-male dance displays. Males give at least 13 distinct vocalizations, several of which occur in clear behavioral contexts. By observing the behavioral context and the sequencein which calls were given, we found that the most frequent calls occurred during three types of activity: song bouts, dance, and noncourtship interactions. The responsesof males to playback of six vocalizations indicated that the calls function as much in mediating cooperative inter- actions as in expressingmale-male agonism. The evolution of the large vocal repertoire in Long-tailed Manakins may be associatedwith their unique social system based on long- term, cooperative relationshipsamong males. Key words: Vocalization;call function; Long-tailed Manakin; Chiroxiphia linearis; so- ciality; cooperation,lek. Resumen. Estudiamosel repertorio vocal de1Saltarin Toledo (Chiroxiphia linearis, Pi- pridae) en Monteverde, Costa Rica. Los machos de este genera se comportan muy parti- cularesen relacibn el cortejo cooperative, incluyendo cancionesa duo y danzascoordinadas de parejasde machos. Los machos emiten al menos 13 vocalizacionesdistintas, muchasde ellas con un context0 claro con respeto al comportamiento. -

Patterns of Individual Relatedness at Blue Manakin (Chiroxiphia Caudata) Leks Author(S): Mercival R

Patterns of Individual Relatedness at Blue Manakin (Chiroxiphia Caudata) Leks Author(s): Mercival R. Francisco, H. Lisle Gibbs and Pedro M. Galetti, Jr. Source: The Auk, 126(1):47-53. Published By: The American Ornithologists' Union URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1525/auk.2009.08030 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. The Auk 126(1):47 53, 2009 The American Ornithologists’ Union, 2009. Printed in USA. PATTERNS OF INDIVIDUAL RELATEDNESS AT BLUE MANAKIN (CHIROXIPHIA CAUDATA) LEKS MERCIVAL R. FRANCISCO,1,4 H. LISLE GIBBS,2 AND PEDRO M. GALETTI, JR.3 1Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Campus de Sorocaba, CEP 18043-970, Caixa Postal 3031, Sorocaba, SP, Brazil; 2Department of Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology, Ohio State University, 300 Aronoff Laboratory, 318 W. 12th Avenue, Columbus, Ohio, USA; and 3Departamento de Genética e Evolução, Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Rod. -

Species Composition and Spatial Ecology of Amazonian Understory

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 Species Composition and Spatial Ecology of Amazonian Understory Mixed-Species Flocks in a Fragmented Landscape Karl Mokross Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Mokross, Karl, "Species Composition and Spatial Ecology of Amazonian Understory Mixed-Species Flocks in a Fragmented Landscape" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 674. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/674 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SPECIES COMPOSITION AND SPATIAL ECOLOGY OF AMAZONIAN UNDERSTORY MIXED-SPECIES FLOCKS IN A FRAGMENTED LANDSCAPE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Renewable Natural Resources by Karl S. Mokross B.S., Universidade Federal de São Carlos, 2001 M.S., Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, 2004 December 2014 Dedicado a Thomas C. e Marina. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Aos mateiros do PDBFF; poucas pesquisas na Amazônia teriam sido realizadas sem sua ajuda. Vocês merecem uma enorme parcela de crédito neste trabalho. Jairo Lopez e Léo Marajó foram grandes professores, obrigado por me ensinarem a caminhar pela mata. À todos que me ajudaram em campo, muito obrigado por sua ajuda. -

The Vocal Behaviour of Long-Tailed Manakins (Chiroxiphia Linearis): the Role of Vocalizations in Mate Attraction and Male-Male Interactions

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholarship at UWindsor University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 2012 The vocal behaviour of long-tailed manakins (Chiroxiphia linearis): The role of vocalizations in mate attraction and male-male interactions Dugan Finn Maynard University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Maynard, Dugan Finn, "The vocal behaviour of long-tailed manakins (Chiroxiphia linearis): The role of vocalizations in mate attraction and male-male interactions" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 5619. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/5619 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. THE VOCAL BEHAVIOUR OF LONG‐TAILED MANAKINS (CHIROXIPHIA LINEARIS): THE ROLE OF VOCALIZATIONS IN MATE ATTRACTION AND MALE‐MALE INTERACTIONS. by DUGAN FINN MAYNARD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through the Department of Biological Sciences in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada 2012 © 2012 Dugan F. -

Display and Related Behavior of Male Pin-Tailed Manakins

Wilson Bull., 97(3), 1985, pp. 273-282 DISPLAY AND RELATED BEHAVIOR OF MALE PIN-TAILED MANAKINS BARBARA K. SNOW AND D. W. SNOW One of the most striking members of the highly endemic avifauna of the southeast Brazilian coastal forests is the Pin-tailed Manakin (Ilicura militaris). The species has been placed in a monotypic genus, and does not appear to be closely related to any other manakin. The bird is little known, apart from brief references to its display by Sick (1959, 1967) and its nest is undescribed. In this paper we describe the behavior of male Pin-tailed Manakins, and compare their displays with those of other man- akin species. METHODS We studied the Pin-tailed Manakin in the Boractia Forest Reserve, in the Serra do Mar about 80 km east of Sgo Paulo, at an altitude of 850 m above sea level. Observations of males in their display territories totaled 44.5 h on 21 d between 14 November and 13 December 1983. We chose this period as it is at or near the height of the breeding season for most of the forest birds of southeastern Brazil. All detailed observations were made on four individual males, one ofwhich was watched for 30-min periods in each hour throughout a complete day; the presence of seven other individuals was noted, but their displays were not recorded. Observations were made with 10 x binoculars, usually at distances of 8-l 5 m. No blind was used, as the birds seemed unaffected by our presence. Tape recordings of their vocalizations were made with a Sony TC 800 B tape recorder and analyzed by sonagraph (Ray 6061B) and by Unigon Spectrum Analyser. -

Bird Nests What Is a Bird's Nest?

Duke Gardens Winter Fun at Home BIRD NESTS Winter can be a good time to spot bird nests in bare tree branches that lost their leaves in the fall. Have you ever spotted any bird nests or squirrel dreys in a tree? (Drey is the word for a squirrel nest, and they usually look like a messy ball of sticks and leaves). WHAT IS A BIRD’S NEST? All birds start their life cycle as an egg. Eggs need to be protected from weather and predators. An egg also needs to stay warm from the time it is laid until it hatches. This is called the incubation period. A nest is the shelter most adult birds build to protect their eggs until A squirrel drey they hatch and to keep baby birds safe until they are ready to leave (not a bird nest!) the nest. Nests range in size, shape, location and building materials, and all of these can be clues about the kind of bird that made it. For example, bald eagle nests can be 5-6 feet across, while a cardinal’s nest is about 4 inches across. Hummingbird nests can be as small as a thimble when they are built, but they are made with materials that allow the nest to stretch as the baby birds inside it grow. Nests can be built in many places. Some birds make cavity nests inside something by finding or making an opening inside a tree, a stump or a nest box. Carolina wrens, chickadees, nuthatches, woodpeckers, and some owls are a few examples of cavity nesting birds. -

Eastern Gray Squirrel Sciurus Carolinensis

eastern gray squirrel Sciurus carolinensis Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata The eastern gray squirrel’s head-body length is Class: Mammalia between eight and 11 inches, with its tail about the Order: Rodentia same length as the body. Its body fur is gray, and there is a border of white fur on the bushy, gray tail. Family: Sciuridae The belly fur is white, a cream line surrounds each ILLINOIS STATUS eye, and white tips are present on the back of the ears. common, native BEHAVIORS The eastern gray squirrel may be found statewide in Illinois. It lives in woods or forests that have a closed canopy, nut-bearing trees and plenty of cavity trees. As these mature forests have been destroyed in Illinois, the population of gray squirrels has declined. However, gray squirrels are common in cities. Here, they live in trees without the conditions described above. The gray squirrel eats buds, leaves, fruits, berries, fungi, pecans, acorns, hickory nuts, tree bark, walnuts and the seeds of various other trees. It stores nuts in holes in the ground. This squirrel grasps food in its front paws. It is primarily arboreal, and its large, bushy tail helps it balance while climbing and resting in trees. Urban squirrels are good at climbing brick walls and walking along wires and cables. The eastern gray squirrel does not hibernate and is active during the day year-round. It ILLINOIS RANGE may sleep for several consecutive days in winter, however. Its call is “kuk-kuk-cut-cut-cut.” This animal builds a leaf nest in the high branches of a tree but may use a tree cavity for escape from predators and poor weather and for raising its young.