Gingoog City's Total Integrated Development Approach (G-TIDA)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

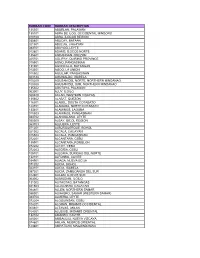

DIRECTORY of PDIC MEMBER RURAL BANKS As of 27 July 2021

DIRECTORY OF PDIC MEMBER RURAL BANKS As of 27 July 2021 NAME OF BANK BANK ADDRESS CONTACT NUMBER * 1 Advance Credit Bank (A Rural Bank) Corp. (Formerly Advantage Bank Corp. - A MFO RB) Stop Over Commercial Center, Gerona-Pura Rd. cor. MacArthur Highway, Brgy. Abagon, Gerona, Tarlac (045) 931-3751 2 Agribusiness Rural Bank, Inc. 2/F Ropali Plaza Bldg., Escriva Dr. cor. Gold Loop, Ortigas Center, Brgy. San Antonio, City of Pasig (02) 8942-2474 3 Agricultural Bank of the Philippines, Inc. 121 Don P. Campos Ave., Brgy. Zone IV (Pob.), City of Dasmariñas, Cavite (046) 416-3988 4 Aliaga Farmers Rural Bank, Inc. Gen. Luna St., Brgy. Poblacion West III, Aliaga, Nueva Ecija (044) 958-5020 / (044) 958-5021 5 Anilao Bank (Rural Bank of Anilao (Iloilo), Inc. T. Magbanua St., Brgy. Primitivo Ledesma Ward (Pob.), Pototan, Iloilo (033) 321-0159 / (033) 362-0444 / (033) 393-2240 6 ARDCIBank, Inc. - A Rural Bank G/F ARDCI Corporate Bldg., Brgy. San Roque (Pob.), Virac, Catanduanes (0908) 820-1790 7 Asenso Rural Bank of Bautista, Inc. National Rd., Brgy. Poblacion East, Bautista, Pangasinan (0917) 817-1822 8 Aspac Rural Bank, Inc. ASPAC Bank Bldg., M.C. Briones St. (Central Nautical Highway) cor. Gen. Ricarte St., Brgy. Guizo, City of Mandaue, Cebu (032) 345-0930 9 Aurora Bank (A Microfinance-Oriented Rural Bank), Inc. GMA Farms Building, Rizal St., Brgy. V (Pob.), Baler, Aurora (042) 724-0095 10 Baclaran Rural Bank, Inc. 83 Redemptorist Rd., Brgy. Baclaran, City of Parañaque (02) 8854-9551 11 Balanga Rural Bank, Inc. Don Manuel Banzon Ave., Brgy. -

Harnessing Rural Radio for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in the Philippines

Harnessing Rural Radio for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in the Philippines Working Paper No. 275 CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) Rex L. Navarro Renz Louie V. Celeridad Rogelio P. Matalang Hector U. Tabbun Leocadio S. Sebastian 1 Harnessing Rural Radio for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in the Philippines Working Paper No. 275 CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) Rex L. Navarro Renz Louie V. Celeridad Rogelio P. Matalang Hector U. Tabbun Leocadio S. Sebastian 2 Correct citation: Navarro RL, Celeridad RLV, Matalang RP, Tabbun HU, Sebastian LS. 2019. Harnessing Rural Radio for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in the Philippines. CCAFS Working Paper no. 275. Wageningen, the Netherlands: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Available online at: www.ccafs.cgiar.org Titles in this Working Paper series aim to disseminate interim climate change, agriculture and food security research and practices and stimulate feedback from the scientific community. The CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) is a strategic partnership of CGIAR and Future Earth, led by the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT). The Program is carried out with funding by CGIAR Fund Donors, Australia (ACIAR), Ireland (Irish Aid), Netherlands (Ministry of Foreign Affairs), New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs & Trade; Switzerland (SDC); Thailand; The UK Government (UK Aid); USA (USAID); The European Union (EU); and with technical support from The International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). For more information, please visit https://ccafs.cgiar.org/donors. Contact: CCAFS Program Management Unit, Wageningen University & Research, Lumen building, Droevendaalsesteeg 3a, 6708 PB Wageningen, the Netherlands. -

Energy Projects in Region X

Energy Projects in Region X Lisa S. Go Chief, Investment Promotion Office Department of Energy Energy Investment Briefing – Region X 16 August 2018 Cagayan De Oro City, Misamis Oriental Department of Energy Empowering the Filipino Energy Projects in Northern Mindanao Provinces Capital Camiguin Mambajao Camiguin Bukidnon Malaybalay Misamis Oriental Cagayan de Oro Misamis Misamis Misamis Occidental Oroquieta Occidental Gingoog Oriental City Lanao del Norte Tubod Oroquieta CIty Cagayan Cities De Oro Cagayan de Oro Highly Urbanized (Independent City) Iligan Ozamis CIty Malaybalay City Iligan Highly Urbanized (Independent City) Tangub CIty Malayabalay 1st Class City Bukidnon Tubod 1st Class City Valencia City Gingoog 2nd Class City Valencia 2nd Class City Lanao del Ozamis 3rd Class City Norte Oroquieta 4th Class City Tangub 4th Class City El Salvador 6th Class City Source: 2015 Census Department of Energy Empowering the Filipino Energy Projects in Region X Summary of Energy Projects Per Province Misamis Bukidnon Camiguin Lanao del Norte Misamis Oriental Total Occidental Province Cap. Cap. Cap. Cap. No. No. No. No. Cap. (MW) No. No. Cap. (MW) (MW) (MW) (MW) (MW) Coal 1 600 4 912 1 300 6 1,812.0 Hydro 28 338.14 12 1061.71 8 38.75 4 20.2 52 1,458.8 Solar 4 74.49 1 0.025 13 270.74 18 345.255 Geothermal 1 20 1 20.0 Biomass 5 77.8 5 77.8 Bunker / Diesel 4 28.7 1 4.1 2 129 6 113.03 1 15.6 14 290.43 Total 41 519.13 1 4.10 16 1,790.74 32 1,354.52 6 335.80 96 4,004.29 Next Department of Energy Empowering the Filipino As of December 31, 2017 Energy Projects in Region X Bukidnon 519.13 MW Capacity Project Name Company Name Location Resource (MW) Status 0.50 Rio Verde Inline (Phase I) Rio Verde Water Constortium, Inc. -

Gingoog City's Total Integrated Development

REACHING OUT: GINGOOG CITY’S TOTAL INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT APPROACH (G-TIDA) Virginia S. Pineda and Clark Clarete1 I. CITY BACKGROUND Location, Land Area, and Population Gingoog City is on the northern coast of Misamis Oriental, 122 kilometers east of Cagayan de Oro City and 74 kilometers west of Butuan City. It has a total land area of 404.6 square kilometers, 1.71 percent of which is classified as urban areas. Around 56 percent of its total area are public forest lands (both classified and unclassified forests). The city is composed of 79 barangays, of which 29 are classified as urban and 50 as rural barangays. As of 1995, it has about 17,128 households. In 1990, the city’s population was estimated at 82,852 persons. By 1995, it has grown to 87,530 persons or by about 5.65 percent (National Statistics Office). Of these, 32.51 percent live in urban areas and 67.48 percent in rural areas. Population density per square kilometer slightly increased from 204 in 1990 to 216 in 1995. Family Income Currently, about 3,924 households consisting roughly 23 percent of the population live within the poverty threshold level (with average gross family income of P6,000 and below per month). The middle income group (with average gross family income of P6,001 to P40,000 a month) constitutes 68 percent (11,601 households) while the high-income group (over P40,000 a month) makes up the remaining 9 percent (1,603 households). Health Facilities The health facilities of Gingoog City include one government hospital - the Gingoog District Hospital (run by the provincial government), two private hospitals, one Main Health Center (located within the urban core), and 50 Barangay Health Stations or BHSs (one for each rural barangay). -

2015Suspension 2008Registere

LIST OF SEC REGISTERED CORPORATIONS FY 2008 WHICH FAILED TO SUBMIT FS AND GIS FOR PERIOD 2009 TO 2013 Date SEC Number Company Name Registered 1 CN200808877 "CASTLESPRING ELDERLY & SENIOR CITIZEN ASSOCIATION (CESCA)," INC. 06/11/2008 2 CS200719335 "GO" GENERICS SUPERDRUG INC. 01/30/2008 3 CS200802980 "JUST US" INDUSTRIAL & CONSTRUCTION SERVICES INC. 02/28/2008 4 CN200812088 "KABAGANG" NI DOC LOUIE CHUA INC. 08/05/2008 5 CN200803880 #1-PROBINSYANG MAUNLAD SANDIGAN NG BAYAN (#1-PRO-MASA NG 03/12/2008 6 CN200831927 (CEAG) CARCAR EMERGENCY ASSISTANCE GROUP RESCUE UNIT, INC. 12/10/2008 CN200830435 (D'EXTRA TOURS) DO EXCEL XENOS TEAM RIDERS ASSOCIATION AND TRACK 11/11/2008 7 OVER UNITED ROADS OR SEAS INC. 8 CN200804630 (MAZBDA) MARAGONDONZAPOTE BUS DRIVERS ASSN. INC. 03/28/2008 9 CN200813013 *CASTULE URBAN POOR ASSOCIATION INC. 08/28/2008 10 CS200830445 1 MORE ENTERTAINMENT INC. 11/12/2008 11 CN200811216 1 TULONG AT AGAPAY SA KABATAAN INC. 07/17/2008 12 CN200815933 1004 SHALOM METHODIST CHURCH, INC. 10/10/2008 13 CS200804199 1129 GOLDEN BRIDGE INTL INC. 03/19/2008 14 CS200809641 12-STAR REALTY DEVELOPMENT CORP. 06/24/2008 15 CS200828395 138 YE SEN FA INC. 07/07/2008 16 CN200801915 13TH CLUB OF ANTIPOLO INC. 02/11/2008 17 CS200818390 1415 GROUP, INC. 11/25/2008 18 CN200805092 15 LUCKY STARS OFW ASSOCIATION INC. 04/04/2008 19 CS200807505 153 METALS & MINING CORP. 05/19/2008 20 CS200828236 168 CREDIT CORPORATION 06/05/2008 21 CS200812630 168 MEGASAVE TRADING CORP. 08/14/2008 22 CS200819056 168 TAXI CORP. -

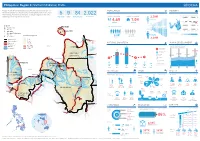

PHL-OCHA-R10 Profile-A3

Philippines: Region X (Northern Mindanao) Profile Region X (Northern Mindanao) occupies the north-central part of POPULATION POVERTY Mindanao Island. It is bordered by the Mindanao Sea on the north, Source: PSA 2015 Census Source: PSA 2016 Zamboanga Peninsula on the west, Caraga Region on the east, 5 9 84 2,022 Poverty incidence among population (%) and Regions XI and XII on the south. PROVINCES CITIES MUNICIPALITIES BARANGAYS Region X population Region X households 2.30M 60% 49.0% 40.1% 4.69 1.04 40% million million 39.0% 39.5% 36.6% Legend Female 20% 4 9 4 9 4 9 4 9 4 9 4 4 9 6 5 1 1 2 2 3 3 4 4 Population statistics trend 5 - - - - - - - - - - - - Mambajao - 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 65+ 6 5 1 1 2 2 3 3 4 4 Provincial capital 5 0 Major city Male 2006 2009 2012 2015 Major airport CAMIGUIN Minor airport (Philippines only) % Poverty incidence Major port Population Density (per km 4.69M 4.30M 51.0% 0 - 14 15 - 26 27 - 39 40 - 56 57 - 84 Active volcano 2015 Census 2010 Census 0 - 5 2.39M Region boundary 6 - 25 Province boundary 26 - 50 51 - 100 Gingoog Bay Primary road NATURAL DISASTERS HUMAN DEVELOPMENT 101 - 500 Secondary road 551 501 - 2,500 Bohol Sea Source: OCD/NDRRMC Conditional cash transfer Source: DSWD Main river 2,501 - 5,000 Gingoog beneficiaries (children) Perennial lake > 5,000 Number of disaster 407 incidents per year Affected population 643,900 (in thousands) MISAMIS 42 595,700 39 Notable incidents 557,200 Typhoon 506,300 312,203 ORIENTAL Girls 20 291,880 272,066 15 16 Flooding Macajalar Bay 248,531 331,717 only includes -

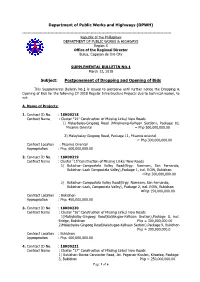

Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) Subject

Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS & HIGHWAYS Region X Office of the Regional Director Bulua, Cagayan de Oro City SUPPLEMENTAL BULLETIN NO.1 March 12, 2018 Subject: Postponement of Dropping and Opening of Bids This Supplemental Bulletin No.1 is issued to postpone until further notice the Dropping & Opening of Bids for the following CY 2018 Regular Infrastructure Projects due to technical reason, to wit: A. Name of Projects: 1. Contract ID No. : 18K00218 Contract Name : Cluster "14" Construction of Missing Links/ New Roads 1) Malaybalay-Gingoog Road (Minalwang-Kalhaan Section), Package 10, Misamis Oriental = Php 300,000,000.00 2) Malaybalay-Gingoog Road, Package 11, Misamis oriental = Php 300,000,000.00 Contract Location : Misamis Oriental Appropriation : Php. 600,000,000.00 2. Contract ID No. : 18K00219 Contract Name : Cluster "15"Construction of Missing Links/ New Roads 1) Bukidnon-Compostela Valley Road(Brgy. Namnam, San Fernando, Bukidnon-Laak Compostela Valley),Package 1, incl. ROW, Bukidnon =Php 300,000,000.00 2) Bukidnon-Compostela Valley Road(Brgy. Namnam, San Fernando, Bukidnon-Laak, Compostela Valley), Package 2, incl. ROW, Bukidnon =Php 150,000,000.00 Contract Location : Bukidnon Appropriation : Php. 450,000,000.00 3. Contract ID No. : 18K00220 Contract Name : Cluster "16" Construction of Missing Links/ New Roads 1)Malaybalay-Gingoog Road(Kalabugao-Kalhaan Section),Package 8, incl. Bridge, Bukidnon Php = 300,000,000.00 2)Malaybalay-Gingoog Road(Kalabugao-Kalhaan Section),Package 9, Bukidnon Php = 300,000,000.0 Contract Location : Bukidnon Appropriation : Php. 600,000,000.00 4. Contract ID No. -

Regional Director's Corner

REGIONAL DIRECTOR’S CORNER Period Covered: JULY 2020 Regional Director’s Activities: July 1, 2020 @ 1:30 PM Courtesy visit to BGEN OLIVER T VESLIÑO, Assistant Division Commander, 4ID, AFP at Camp Evangelista, Patag, Cagayan de Oro City Discussed were PDEA-AFP joint forces of any possible conduct of Marijuana Eradication Operation and other future Anti-Drug efforts engagements. July 1, 2020 @ 3:30 PM Courtesy visit to PCOL RONALDO R CABRAL, Deputy Regional Director for Operation, Police Regional Office 10 at Camp Alagar, Lapasan, Cagayan de Oro City Discussed were Barangay Drug Clearing Program and Anti-Drug Operations in the region. Further, DRD Cabral July 6, 2020 @ 8:30 AM Courtesy visit to Hon. Rogelio Neil P. Roque, 4th District Representative, of the Province of Bukidnon and the City Councilor of Valencia, Atty. Teodoro Roteo Pepito at El Comedor Seafoods Grill and Restaurant, Valencia City, Bukidnon. Discussed were the continue support to the PDEA Bukidnon Provincial Office and to provide safe house/office in Valencia City, Bukidnon. July 6, 2020 @ 10:30 AM Courtesy visit to Hon. Azucena P. Huervas, City Mayor of Valencia City, Bukidnon at the Mayor’s Office, City Hall of Valencia City, Bukidnon. Discussed were the continued support and implementation of Valencia City Local Government to the Barangay Drug Clearing Program in the City as previously agreed with PDEA DG Villanueva despite the realignment of budget caused by Covid-19 pandemic. July 7, 2020 @ 3:00 PM Courtesy visit to PBGEN ROLANDO B ANDUYAN, Regional Director of Police Regional Office 10 (PRO-10) at Camp Alagar, Lapasan, Cagayan de Oro City. -

List of Ecpay Cash-In Or Loading Outlets and Branches

LIST OF ECPAY CASH-IN OR LOADING OUTLETS AND BRANCHES # Account Name Branch Name Branch Address 1 ECPAY-IBM PLAZA ECPAY- IBM PLAZA 11TH FLOOR IBM PLAZA EASTWOOD QC 2 TRAVELTIME TRAVEL & TOURS TRAVELTIME #812 EMERALD TOWER JP RIZAL COR. P.TUAZON PROJECT 4 QC 3 ABONIFACIO BUSINESS CENTER A Bonifacio Stopover LOT 1-BLK 61 A. BONIFACIO AVENUE AFP OFFICERS VILLAGE PHASE4, FORT BONIFACIO TAGUIG 4 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HEAD OFFICE 170 SALCEDO ST. LEGASPI VILLAGE MAKATI 5 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BF HOMES 43 PRESIDENTS AVE. BF HOMES, PARANAQUE CITY 6 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BETTER LIVING 82 BETTERLIVING SUBD.PARANAQUE CITY 7 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_COUNTRYSIDE 19 COUNTRYSIDE AVE., STA. LUCIA PASIG CITY 8 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_GUADALUPE NUEVO TANHOCK BUILDING COR. EDSA GUADALUPE MAKATI CITY 9 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HERRAN 111 P. GIL STREET, PACO MANILA 10 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_JUNCTION STAR VALLEY PLAZA MALL JUNCTION, CAINTA RIZAL 11 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_RETIRO 27 N.S. AMORANTO ST. RETIRO QUEZON CITY 12 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_SUMULONG 24 SUMULONG HI-WAY, STO. NINO MARIKINA CITY 13 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP 10TH 245- B 1TH AVE. BRGY.6 ZONE 6, CALOOCAN CITY 14 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP B. BARRIO 35 MALOLOS AVE, B. BARRIO CALOOCAN CITY 15 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP BUSTILLOS TIWALA SA PADALA L2522- 28 ROAD 216, EARNSHAW BUSTILLOS MANILA 16 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CALOOCAN 43 A. MABINI ST. CALOOCAN CITY 17 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CONCEPCION 19 BAYAN-BAYANAN AVE. CONCEPCION, MARIKINA CITY 18 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP JP RIZAL 529 OLYMPIA ST. JP RIZAL QUEZON CITY 19 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP LALOMA 67 CALAVITE ST. -

Flash Floods

Information bulletin n° 2 Philippines: GLIDE n˚ FL-2009-000011-PHL 22 January 2009 Flash floods This bulletin is being issued for information only. A cold front and continuous rains from 7-12 January 2009 caused flash floods, landslides, and sea surges in large areas of the country, affecting some 329,0451 people. The Philippine National Red Cross Society (PNRCS), with support from the International Federation, has responded by undertaking assessments to identify numbers of people affected and needs, as well as to begin the delivery of relief assistance and arrange temporary shelters. The PNRCS has determined that external assistance is not required at this time, and is therefore not presently seeking funding or other assistance from donors. <view contact information> The Situation The Philippines, particularly prone to natural disasters, has been experiencing weather disturbances in recent days. The tail-end of a cold front affecting the Bicol region and eastern sections of Visayas and Mindanao from 7- 12 January 2009 triggered the occurrence of continuous rains which caused flash floods, flooding, landslides and sea surges in some areas of the country. Severely affected by the brunt of the continuous rains were the cities of Cagayan de Oro and Gingoog, and the provinces of Misamis Oriental and Northern Samar. At the same time, high tides with big waves struck in Aringay, La Union, Surigao City; Siargao Island, Bucas Grande Island and Dinagat Island in Surigao del Norte Province, Surigao del Sur, Agusan del Norte, Agusan del Sur, Compostela Valley and Davao del Norte. It is important to note that Cagayan de Oro City, Misamis Oriental and Gingoog City have not experienced any floods since 1950s till now; therefore, creating additional challenges for local coping and response capacities. -

Rurban Code Rurban Description 135301 Aborlan

RURBAN CODE RURBAN DESCRIPTION 135301 ABORLAN, PALAWAN 135101 ABRA DE ILOG, OCCIDENTAL MINDORO 010100 ABRA, ILOCOS REGION 030801 ABUCAY, BATAAN 021501 ABULUG, CAGAYAN 083701 ABUYOG, LEYTE 012801 ADAMS, ILOCOS NORTE 135601 AGDANGAN, QUEZON 025701 AGLIPAY, QUIRINO PROVINCE 015501 AGNO, PANGASINAN 131001 AGONCILLO, BATANGAS 013301 AGOO, LA UNION 015502 AGUILAR, PANGASINAN 023124 AGUINALDO, ISABELA 100200 AGUSAN DEL NORTE, NORTHERN MINDANAO 100300 AGUSAN DEL SUR, NORTHERN MINDANAO 135302 AGUTAYA, PALAWAN 063001 AJUY, ILOILO 060400 AKLAN, WESTERN VISAYAS 135602 ALABAT, QUEZON 116301 ALABEL, SOUTH COTABATO 124701 ALAMADA, NORTH COTABATO 133401 ALAMINOS, LAGUNA 015503 ALAMINOS, PANGASINAN 083702 ALANGALANG, LEYTE 050500 ALBAY, BICOL REGION 083703 ALBUERA, LEYTE 071201 ALBURQUERQUE, BOHOL 021502 ALCALA, CAGAYAN 015504 ALCALA, PANGASINAN 072201 ALCANTARA, CEBU 135901 ALCANTARA, ROMBLON 072202 ALCOY, CEBU 072203 ALEGRIA, CEBU 106701 ALEGRIA, SURIGAO DEL NORTE 132101 ALFONSO, CAVITE 034901 ALIAGA, NUEVA ECIJA 071202 ALICIA, BOHOL 023101 ALICIA, ISABELA 097301 ALICIA, ZAMBOANGA DEL SUR 012901 ALILEM, ILOCOS SUR 063002 ALIMODIAN, ILOILO 131002 ALITAGTAG, BATANGAS 021503 ALLACAPAN, CAGAYAN 084801 ALLEN, NORTHERN SAMAR 086001 ALMAGRO, SAMAR (WESTERN SAMAR) 083704 ALMERIA, LEYTE 072204 ALOGUINSAN, CEBU 104201 ALORAN, MISAMIS OCCIDENTAL 060401 ALTAVAS, AKLAN 104301 ALUBIJID, MISAMIS ORIENTAL 132102 AMADEO, CAVITE 025001 AMBAGUIO, NUEVA VIZCAYA 074601 AMLAN, NEGROS ORIENTAL 123801 AMPATUAN, MAGUINDANAO 021504 AMULUNG, CAGAYAN 086401 ANAHAWAN, SOUTHERN LEYTE -

REGION 10 Address: Baloy, Cagayan De Oro City Office Number: (088) 855 4501 Email: [email protected] Regional Director: John Robert R

REGION 10 Address: Baloy, Cagayan de Oro City Office Number: (088) 855 4501 Email: [email protected] Regional Director: John Robert R. Hermano Mobile Number: 0966-6213219 Asst. Regional Director: Rafael V Marasigan Mobile Number: 0917-1482007 Provincial Office : BUKIDNON Address : Capitol Site, Malaybalay, Bukidnon Office Number : (088) 813 3823 Email Address : [email protected] Provincial Manager : Leo V. Damole Mobile Number : 0977-7441377 Buying Station : GID Aglayan Location : Warehouse Supervisor : Joyce Sale Mobile Number : 0917-1150193 Service Areas : Malaybalay, Cabanglasan, Sumilao and Impsug-ong Buying Station : GID Valencia Location : Warehouse Supervisor : Rhodnalyn Manlawe Mobile Number : 0935-9700852 Service Areas : Valencia, San Fernando and Quezon Buying Station : GID Kalilangan Location : Warehouse Supervisor : Catherine Torregosa Mobile Number : 0965-1929002 Service Areas : Kalilangan Buying Station : GID Wao Location : Warehouse Supervisor : Catherine Torregosa Mobile Number : 0965-1929002 Service Areas : Wao, and Banisilan, North Cotabato Buying Station : GID Musuan Location : Warehouse Supervisor : John Ver Chua Mobile Number : 0975-1195809 Service Areas : Musuan, Quezon, Valencia, Maramag Buying Station : GID Maramag Location : Warehouse Supervisor : Rodrigo Tobias Mobile Number : 0917-7190363 Service Areas : Pangantucan, Kibawe, Don Carlos, Maramag, Kitaotao, Kibawe, Damulog Provincial Office : CAMIGUIN Address : Govt. Center, Lakas, Mambajao Office Number : (088) 387 0053 Email Address : [email protected]