Towards a More Effective EU Foreign and Security Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Market Power and Joint Ownership: Evidence from Nuclear Plants in Sweden

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Lundin, Erik Working Paper Market power and joint ownership: Evidence from nuclear plants in Sweden IFN Working Paper, No. 1113 Provided in Cooperation with: Research Institute of Industrial Economics (IFN), Stockholm Suggested Citation: Lundin, Erik (2016) : Market power and joint ownership: Evidence from nuclear plants in Sweden, IFN Working Paper, No. 1113, Research Institute of Industrial Economics (IFN), Stockholm This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/175050 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu IFN Working Paper No. 1113, 2016 Market Power and Joint Ownership: Evidence from Nuclear Plants in Sweden Erik Lundin Research Institute of Industrial Economics P.O. -

CR1967 11.Pdf

NOVEMBER 1967 FINE VICTORY AT HAVANA and GOOD TIE AT WINNIPEG ( Set PllO" ) 2$ .:ond pig" 323) 65 CENTS Subscription Rat. ONE YEAR 57.50 e wn 789 7 'h by 9 Inches. clothbound 221 diagrams 493 idea Yariations 1704 practical yariations 463 supplementary variations 3894 notes to all yariations and 439 COMPLETE GAMES! BY I. A . HOROWITZ in collaboration with Former World Champion, Dr. Max Euwe. Ernest Gruenfeld, Hans Kmoch. and many other noted authorities This latest Hild immense work, the most exhaustive of its kind, ex· plains in encyclopedic detail the fine points of all openings. It carries the reader well into the middle game, evaluates the prospects there and often gives complete exemplary games so that he is not left hanging in mid.position with the query: What happens now? A logical sequence binds the continuity in each opening. First come the moves with footnotes leading to the key positi on. Then fol· BIBLIOPHILES! low pertinent observations, illustrated by " Idea Variations." Finally, Glossy paper, handsome print, Practical and Supplementary Va riations, well annotated, exemplify the spaciolls paging and all the effective po::isibilities. Each line is appraised: +. - or =. The hi rge format- 71f2 x 9 inches-is designed for ease of read· other appurtenances of exqllis ing and playing. It eliminates much tiresome shuIIling of pages ite book-making combine to between the principal Jines and the respective comments. Clear, make this the handsomest of legible type, a wide margin for inserting notes and variation-identify. ing diagrams are olher plus features. chess books! In addition to all else. -

Separata ITAN Tomo 3.Indd

EL IMPRESIONANTE TORNEO DE AJEDREZ DE LAS NACIONES 1939 JJuanuan SSebastiánebastián MorgadoMorgado ATA PAR SSEPARATAE TOMO JUAN SEBASTIÁN MORGADO EL IMPRESIONANTE TORNEO DE AJEDREZ DE LAS NACIONES 1939 Obra Completa 978-987-47437-0-1 Morgado, Juan Sebastián El impresionante Torneo de Ajedrez de las Naciones 1939: los inmigrantes enriquecen al ajedrez argentino: 1940-1943 / Juan Sebastián Morgado. - 1a ed ilustrada. - Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires : Ajedrez de Estilo, 2019. v. 3, 590 p. ; 30 x 32 cm. ISBN 978-987-47437-3-2 1. Historia Argentina. 2. Ajedrez. I. Título. CDD 794.1 Hecho el depósito que prevé la ley 11.723 Impreso en la Argentina © 2019 Juan Sebastián Morgado e-mail: [email protected] ISBN 978-987-47437-3-2 CARACTERÍSTICAS DE ESTA COLECCIÓN Esta obra está estructurada como una cronología del Torneo de las Naciones de 1939 en el contexto socio-político en que se desarrolló. La circunstancia de que este autor administrara una ajedrecería durante 38 años (1981-2019) favoreció la progresiva acumulación de materiales his- tóricos y de colección: todas las revistas argentinas de ajedrez, muy diversos libros de recortes, colecciones completas de diarios como La Nación y Crítica, importantes lotes de revistas ex- tranjeras (Chess, British Chess Magazine, Xadrez Brasileiro, Deutsche Schachblätter, Deutsche Schachzeitung, uruguayas, chilenas, cubanas, etc.), documentos oficiales y personales de grandes maestros. La llegada de la tecnología a fines de la década de 1990 facilitó el escaneo, digitalización y clasificación de los elementos, pero el ordenamiento final llevó no menos de 15 años. Los conceptos históricos y culturales que se insertan aquí se fundan en las profundas ideas del escritor Ezequiel Martínez Estrada (1895-1964), principalmente sobre la base de sus obras de las décadas del ’30 y del ’40. -

Painter and Writer. Grob Was a Leading Swiss Player from Th

Grob Henry (04.06.1904 - 05.07.1974) Swiss International Master (1950, inauguration year of FIDE titles). Painter and writer. Grob was a leading swiss player from the 1930s to 1950s, and Swiss Champion in 1939 and 1951. Best results: Barcelona 1935, 3rd; Ostende 1936, 2nd, Ostende 1937, 1-3rd (first on tie-break, alongside with Fine and Keres, ahead of Landau, List, Koltanowski, Tartakower, 10 players; tournament winner Grob beat both, Fine and Keres!), Hastings 1947/48, 2nd-4th (Szabo won) He played multiple matches against strong opposition: He lost to Salomon Flohr (1½-4½) in 1933, beat Jacques Mieses (4½-1½) in 1934, drew with George Koltanowski (2-2), lost to Lajos Steiner 3-1 in 1935, lost to Max Euwe (½-5½) in 1947, lost to Miguel Najdorf (1-5) in 1948, lost to Efim Bogoljubow (2½-4½) in 1949 and to Lodewejk Prins (1½-4½) in 1950 (selection of matches). A participant in the Olympiads of 1927, 1935 and 1952. Addict of the opening 1.g4 (Grob’s attack”) which was deeply analysed in his book Angriff published in 1942. During the period 1940-1973, he was the editor of the chess column published in “Neue Zürcher Zeitung”. Author of “Lerne Schach spielen” (Zürich, 1945, reprinted many times). A professional artist, Grob has published Henry Grob the Artist, a book containing portraits of Grandmasters against whom he played (note: Grob writes his prename with an “y”, not an “i”). Famous game: Flohr, Salo - Grob, Henry Arosa match Arosa (1), 1933 1.d4 d5 2.Nf3 c5 3.dxc5 e6 4.e4 Bxc5 5.Bb5+ Nc6 6.exd5 exd5 7.O-O Nge7 8.Nbd2 O-O 9.Nb3 Bd6 -

A Future Security Agenda for Europe

A Future Security Agenda for Europe Report of the Independent Working Group established by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute October 1996 Stockholm International Peace Research Institute SIPRI is an independent international institute for research into problems of peace and conflict, especially those of arms control and disarmament. It was established in 1966 to commemorate Sweden’s 150 years of unbroken peace. The Institute is financed mainly by the Swedish Parliament. The staff and the Governing Board are international. The Institute also has an Advisory Committee as an international consultative body. The Governing Board is not responsible for the views expressed in the publications of the Institute. Governing Board Professor Daniel Tarschys, Chairman (Sweden) Sir Brian Urquhart, Vice-Chairman (United Kingdom) Dr Oscar Arias Sánchez (Costa Rica) Dr Ryukichi Imai (Japan) Professor Catherine Kelleher (United States) Dr Marjatta Rautio (Finland) Dr Lothar Rühl (Germany) Dr Abdullah Toukan (Jordan) The Director Director Dr Adam Daniel Rotfeld (Poland) Stockholm International Peace Research Institute Frösunda, S-171 53 Solna, Sweden Cable: SIPRI Telephone: 46 8/655 97 00 Telefax: 46 8/655 97 33 Email: [email protected] Internet URL: http://www.sipri.se A Future Security Agenda for Europe Co-chairmen of the Independent Working Group on A Future Security Agenda for Europe Daniel Tarschys, Chairman of the SIPRI Governing Board Adam Daniel Rotfeld, Director of SIPRI A Future Security Agenda for Europe Report of the Independent Working Group established by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute Stockholm, October 1996 © SIPRI, 1996 Contents Preface vii Findings of the Independent Working Group 1 1. -

CIRC Research Symposium 2018 12-14 September 2018 Lecture Theatre, Abisko Scientific Research Station (ANS)

CIRC Research Symposium 2018 12-14 September 2018 Lecture theatre, Abisko Scientific Research Station (ANS) Wednesday 12 September Start of symposium (chair: Karlsson) 17.00-17.15 Introduction, Jan Karlsson 17.15-17.30 The Scientific Advisory Group for Abisko Scientific Research Station (SAGA), Ulf Molau 17.30-18.00 The potential and constraints for greening of the High Arctic, Greg Henry 18.00-19.00 Welcome mixer (ANS dining room) 19.00- Dinner (ANS dining room) Thursday 13 September 07.00-08.00 Breakfast (ANS dining room) Session 1. Climate impact on Ecological dynamics (chair: Dorrepaal) 08.15-08.30 Species asynchrony globally stabilizes primary production against climate variability, Andrew MacDougall 08.30-08.45 The effect of snowmelt gradients on autumn senescence in tundra plants, Friederike Gehrmann 08.45-09.00 Long term effects of increased snow cover on tundra vegetation, Johan Olofsson 09.00-09.15 Fish production in northern lakes, Sven Norman 09.15-09.30 Biodiversity across 40 years in Northern Sweden, Per Stenberg 09.30-10.00 Coffee break (ANS dining room) and fresh air Session 2. Human dimensions of environmental change (chair: Müller) 10.00-10.30 Socio-economic impacts of permafrost thaw in the coastal region of West Greenland: Working with local stakeholders to develop adaptation and mitigation strategies, Joan Nymand Larsen 10.30-10.45 Tourism and Climate Change, Cenk Demiroglu 10.45-11.00 Outdoor Human Environments: the changing face of climatic barriers to soft mobility and gathering in winter communities, David Chapman -

The European Union in the OSCE in the Light of the Ukrainian Crisis: Trading Actorness for Effectiveness? Michaela Anna Šimáková

The European Union in the OSCE in the Light of the Ukrainian Crisis: Trading Actorness for Effectiveness? Michaela Anna Šimáková DEPARTMENT OF EU INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS AND DIPLOMACY STUDIES EU Diplomacy Paper 03 / 2016 Department of EU International Relations and Diplomacy Studies EU Diplomacy Papers 3/2016 The European Union in the OSCE in the Light of the Ukrainian Crisis: Trading Actorness for Effectiveness? Michaela Anna ŠIMÁKOVÁ © Michaela Anna Šimáková Dijver 11 | BE-8000 Bruges, Belgium | Tel. +32 (0)50 477 251 | Fax +32 (0)50 477 250 | E-mail [email protected] | www.coleurope.eu/ird EU Diplomacy Paper 3/2016 About the Author Michaela Anna Šimáková is Academic Assistant at the College of Europe in Bruges, Department of EU International Relations and Diplomacy Studies. She holds an MA in EU International Relations and Diplomacy Studies from the College of Europe and an MA in International Security from SciencesPo Paris (PSIA). She worked for the Slovak Foreign Policy Association and carried out traineeships at the Slovak Ministry of Defence and at the EU Delegation to the International Organisations in Vienna. She also worked for the Lithuanian Presidency of the EU Council and its Delegation to the International Organisations in Vienna and has contributed to the Fostering Human Rights Among European Policies (FRAME) Report on EU engagement with other European regional organisations. Editorial Team: Nicola Del Medico, Tommaso Emiliani, Sieglinde Gstöhl, Ludovic Highman, Sara Hurtekant, Enrique Ibáñez, Simon Schunz, Michaela Šimáková Dijver 11 | BE-8000 Bruges, Belgium | Tel. +32 (0)50 477 251 | Fax +32 (0)50 477 250 | E-mail [email protected] | www.coleurope.eu/ird Views expressed in the EU Diplomacy Papers are those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect positions of either the series editors or the College of Europe. -

CHESS REVIEW 'H( ~IUUU (HISS Iiiaoazinf

AUGUST 1951 EASTER ISLAND CHESS SET (50::e Pllg es 226.233 ) 50 CENTS Subscription Rote ONE YEAR $4.75 This can become dangerous! 19., .. Q-KB1! 22 K_Bl QRxN 20 N_ R7 PxB!! 23 P- B3 Nj2-K4 21 NxQ PxNt 24 QxP NxP! Diac1, bl'eaks open the position f Ol· the powerful doubled Hooks! 25 PxN RxPt 26 K-N2 What's left! If 26 K-Kl, B-N5 pins the Queen; or, If 26 K-Nl, B-BH wins the Queen 01" 26 . R-N6t, followed by 27 . _ . B-Q3, leaves White helpless. N the past few years, Death has taken having met in tournament and match· from us some of the most illustt'ious play sllch stal's as Anderssen. Ste initz, 26 . B-N5! I 27 Q-Bl names in the history of Chess. Blackbur ne, Zukertort, Tanasch and Fit'st, there was Tanasch in 1934, the countless others. Bird had eve n been a ,"Vhlte st!1l hopes to get 28 P-H6 in. man whose games f.ascinate(! the world contestant in the first tournament of 27 .... R-B7t with their classic, clear-cut, logical, po modern chess history, far back in 1851! 28 K-N1 sitional planning. Tarrasch formulated Hastings, 1895 No better Is 28 K-R3, R/l-B6t 29 K- a science out of a rude art, and his teach· N4, N-K4t 30 K-N5, B-K2 mate. ings made masters out of amateurs. FRENCH DEFENSE 28 N_Q5 Then followed his arch-rival, NirnzQ H. E. Bird G. -

Study Protocol Will Receive Photon Therapy According to Local Practice

PROTHYM Phase II non-randomized study on proton radiotherapy of thymic malignancies Version 2.2 21 June 2017 Phase II non-randomized study on Proton Radiotherapy Of Thymic Malignancies Version 2.2 Supported by SLUSG: Swedish Lung cancer Study Group Investigator signature: Date: __________________________________________________________ Principal investigator Jan Nyman, MD, PhD Department of Oncology Sahlgrenska University Hospital 2 Gothenburg [email protected] Study Coordinating center: Department of Oncology, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden Study Participants/ Co investigator Dr Andreas Hallqvist, MD Dr Hedvig Björkestrand, MD Department of Oncology Department of Oncology Sahlgrenska University Hospital University Hospital Karolinska Gothenburg Stockholm [email protected] [email protected] Dr Signe Friesland, MD, PhD Dr Annica Ravn-Fischer, MD, PhD Department of Oncology Department of Cardiology University Hospital Karolinska Sahlgrenska University Hospital Stockholm Gothenburg [email protected] [email protected] Dr Kristina Nilsson, MD, PhD Anna Bäck, Med Phys, PhD Department of Oncology Department of Radiotherapy University Hospital Uppsala Sahlgrenska University Hospital Uppsala Gothenburg kristina.nilsson@akademiska .se [email protected] Dr Per Bergström, MD Dr Jens Engleson, MD Department of Oncology Department of Radiotherapy University Hospital Norrland Skåne University Hospital Umeå Lund per.bergströ[email protected] [email protected] Dr Jan -

The European Union and Weapons of Mass Destruction: a Follow-On to the Global Strategy?

EU NON-PROLIFERATION CONSORTIUM The European network of independent non-proliferation think tanks NON-PROLIFERATION PAPERS No. 58 May 2017 THE EUROPEAN UNION AND WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION: A FOLLOW-ON TO THE GLOBAL STRATEGY? lars-erik lundin I. INTRODUCTION SUMMARY As of mid 2016, the European Union (EU) finally has a The European Union (EU) should undertake a new and new Global Strategy for its foreign and security policy, dedicated effort to deal with the problems related to which is a follow-on to its 2003 Security Strategy.1 In weapons of mass destruction (WMD). More specifically, 2003, in the midst of a heated debate about suspected one or more new strategy documents are required and, in this context, the EU should also pursue WMD-related Iraqi weapon of mass destruction (WMD) capabilities, contingency planning to increase preparedness and the issue of non-proliferation easily made it to the top prevent or counter crises. If the EU does not undertake of the list of priorities. It even led EU leaders to adopt these efforts, something much more will be at stake than a specific WMD strategy at the same time: the EU’s the effectiveness of EU programmes in the areas of non- 2003 Strategy on the Non-proliferation of Weapons of proliferation, arms control and disarmament. The Mass Destruction (EU WMD Strategy). In 2016, the overarching risk is that EU leaders will become reactive situation was different. Many other issues dominated and even confused to a greater and even more dangerous the agenda, and non-proliferation—and for that matter extent than occurred after the terrorist attacks on the arms control—was not given a prominent place among United States of 11 September 2001. -

Mikhail Tal's Best Games 2

Mikhail Tal’s Best Games 2 The World Champion By Tibor Karolyi Quality Chess www.qualitychess.co.uk Contents Key to symbols used & Bibliography 4 Preface 5 Acknowledgements 6 1960 7 1961 67 1962 103 1963 125 1964 149 1965 181 1966 207 1967 235 1968 259 1969 283 1970 295 1971 317 Summary of Results 340 Tournament and Match Wins 341 Classification 343 Game Index by Page Number 344 Game Index by Tal’s Opponents 348 Alphabetical Game Index – Non-Tal games 350 Name Index 351 Preface to Volume 2 The World Champion is the middle volume of our three-part investigation into Mikhail Tal’s life and career. We will rejoin the story after the climactic events of The Magic of Youth, where Tal’s superb score of 20/28 at the 1959 Candidates tournament earned him the right to challenge Botvinnik for the world title. Tal’s 1960 match against Botvinnik was the most eagerly anticipated world championship match in decades. Not only was it a clash between generations; it also featured two strong personalities with diametrically opposing chess philosophies. Tal stunned the chess world (not to mention Botvinnik) with his ferocious attacking style in a way unlike any other player before him. Tal’s career probably featured the most dramatic ups and downs of any world champion. After losing the rematch to Botvinnik he was still one of the strongest players in the world, but his performance was hampered by extensive health problems. Tal’s maverick personality and bohemian lifestyle made him a fan favourite, but were not necessarily conducive to success over the chessboard. -

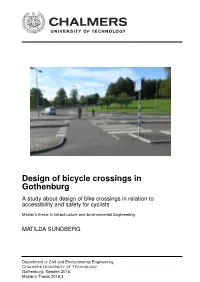

Design of Bicycle Crossings in Gothenburg a Study About Design of Bike Crossings in Relation to Accessibility and Safety for Cyclists

Design of bicycle crossings in Gothenburg A study about design of bike crossings in relation to accessibility and safety for cyclists Master’s thesis in Infrastructure and Environmental Engineering MATILDA SUNDBERG Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Gothenburg, Sweden 2016 Master’s Thesis 2016:3 Master’s thesis 2016:3 Design of bicycle crossings in Gothenburg A study about design of bike crossings in relation to accessibility and safety for cyclists MATILDA SUNDBERG Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Division of GeoEngineering Road and Traffic Research Group Chalmers University of Technology Gothenburg, Sweden 2016 Design of bicycle crossings in Gothenburg - A study about design of bike crossings in relation to accessibility and safety for cyclists MATILDA SUNDBERG © MATILDA SUNDBERG, 2016. Supervisors: Malin Månsson, The Traffic and Public Transport Authority Gunnar Lannér, Civil and Environmental Engineering Examiner: Anders Markstedt, Civil and Environmental Engineering Master’s Thesis 2016:3 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Division of GeoEngineering Road and Traffic Research Group Chalmers University of Technology SE-412 96 Gothenburg Telephone +46 31 772 1000 Cover: Combined crossing in Munkebäck in Gothenburg. Typeset in LATEX Printed by Reproservice Gothenburg, Sweden 2016 IV Design of bicycle crossings in Gothenburg - A study about design of bike crossings in relation to accessibility and safety for cyclists MATILDA SUNDBERG Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Chalmers University of Technology Abstract As fossil fuels are getting more expensive and studies one after another show how the global warming is affected by the transport sector, the interest of finding more environmental friendly alternatives of transportation increases.