Hedonism and History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas on the Mind, Body, and Life After Death

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Williams Honors College, Honors Research The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors Projects College Spring 2020 St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas on the Mind, Body, and Life After Death Christopher Choma [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects Part of the Christianity Commons, Epistemology Commons, European History Commons, History of Philosophy Commons, History of Religion Commons, Metaphysics Commons, Philosophy of Mind Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Recommended Citation Choma, Christopher, "St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas on the Mind, Body, and Life After Death" (2020). Williams Honors College, Honors Research Projects. 1048. https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/1048 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors College at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The University of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Williams Honors College, Honors Research Projects by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 1 St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas on the Mind, Body, and Life After Death By: Christopher Choma Sponsored by: Dr. Joseph Li Vecchi Readers: Dr. Howard Ducharme Dr. Nathan Blackerby 2 Table of Contents Introduction p. 4 Section One: Three General Views of Human Nature p. -

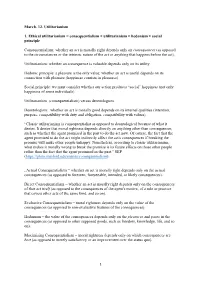

March, 12. Utilitarianism 1. Ethical Utilitarianism = Consequentialism + Utilitarianism + Hedonism + Social Principle Consequent

March, 12. Utilitarianism 1. Ethical utilitarianism = consequentialism + utilitarianism + hedonism + social principle Consequentialism: whether an act is morally right depends only on consequences (as opposed to the circumstances or the intrinsic nature of the act or anything that happens before the act). Utilitarianism: whether an consequence is valuable depends only on its utility Hedonic principle: a pleasure is the only value; whether an act is useful depends on its connection with pleasure (happiness consists in pleasures) Social principle: we must consider whether our action produces “social” happiness (not only happiness of some individuals) Utilitarianism (consequentialism) versus deontologism Deontologism: whether an act is morally good depends on its internal qualities (intention, purpose, compatibility with duty and obligation, compatibility with values) “Classic utilitarianism is consequentialist as opposed to deontological because of what it denies. It denies that moral rightness depends directly on anything other than consequences, such as whether the agent promised in the past to do the act now. Of course, the fact that the agent promised to do the act might indirectly affect the act's consequences if breaking the promise will make other people unhappy. Nonetheless, according to classic utilitarianism, what makes it morally wrong to break the promise is its future effects on those other people rather than the fact that the agent promised in the past.” SEP (https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/consequentialism) „Actual Consequentialism = whether an act is morally right depends only on the actual consequences (as opposed to foreseen, foreseeable, intended, or likely consequences). Direct Consequentialism = whether an act is morally right depends only on the consequences of that act itself (as opposed to the consequences of the agent's motive, of a rule or practice that covers other acts of the same kind, and so on). -

The Legacy of Sovereign

LegacySovereignJoy.48134.int.qxd 9/21/07 10:01 AM Page 1 T HE L EGACY OF S OVEREIGN J OY LegacySovereignJoy.48134.int.qxd 9/21/07 10:01 AM Page 2 OTHER BOOKS BY THE AUTHOR The Justification of God: An Exegetical and Theological Study of Romans 9:1–23 2nd Edition (Baker Book House, 1993, orig. 1983) The Supremacy of God in Preaching (Baker Book House, 1990) The Pleasures of God: Meditations on God’s Delight in Being God (Multnomah Press, 1991) Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood: A Response to Evangelical Feminism (edited with Wayne Grudem, Crossway Books, 1991) What’s the Difference? Manhood and Womanhood Defined According to the Bible (Crossway Books, 1991) Let the Nations Be Glad: The Supremacy of God in Missions (Baker Book House, 1993) The Purifying Power of Living by Faith in Future Grace (Multnomah Press, 1995) Desiring God: Meditations of a Christian Hedonist (Multnomah Press, revised 1996) A Hunger for God: Desiring God through Fasting and Prayer (Crossway Books, 1997) A Godward Life: Savoring the Supremacy of God in All of Life (Multnomah Press, 1997) God’s Passion for His Glory: Living the Vision of Jonathan Edwards (Crossway Books, 1998) The Innkeeper (Crossway Books, 1998) A Godward Life, Book Two: Savoring the Supremacy of God in All of Life (Multnomah Press, 1999) LegacySovereignJoy.48134.int.qxd 9/21/07 10:01 AM Page 3 s a r e n a n o t w s s i l e e n h t t BOOK ONE LegTHEacy of Sovereign Joy God’s Triumphant Grace in the Lives of Augustine, Luther, and Calvin J OHN P IPER CROSSWAY BOOKS A PUBLISHING MINISTRY OF GOOD NEWS PUBLISHERS WHEAT O N , ILLINO IS LegacySovereignJoy.48134.int.qxd 9/21/07 10:01 AM Page 4 The Legacy of Sovereign Joy Copyright © 2000 by John Piper Published by Crossway Books a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers 1300 Crescent Street Wheaton, Illinois 60187 All rights reserved. -

Kant and the Role of Pleasure in Moral Action

Morrisson.1-25 7/11/08 9:02 AM Page 1 INTRODUCTION ............................... methodology and two kinds of ethics Kant’s theory of moral motivation is notoriously controversial. Indeed, few areas of Kant scholarship have drawn as much attention or prompted as much disagreement. Kant himself was so confounded by the issue of how the moral law can provide an incentive that moves the will to action that he refers to this problem as the “philosophers’ stone” (LE 27:1428). Unfortunately, Kant’s perplexity ultimately translates into an unusually elusive theory of moral motivation. As a result, the list of scholars who have presented divergent, often mutually exclusive interpre- tations of Kant’s account of moral motivation is long and distinguished.1 In this study, I want to contribute to the debate over how Kant thinks we are moved to act morally by approaching the issue in a new and, I argue, wholly enlightening way. The problem that is perhaps central to this debate is as follows: how can Kant account for moral motivation while divorcing the basis of morality from the pathological, and therefore motivational, side of human agents?2 To put this pivotal question another way: if Kant thinks that morality is not grounded in our sensuous and affective natures (as the British moral sense theorists suggest), then how does he think we are moved by moral considerations at all? Kant (notoriously) introduces the concept of respect (Achtung) as an answer to this question. On the face of it, his solution seems to be that respect is a moral feeling, and, as such, bridges the gap between the moral law and the capacity of hu- mans—as sensuously affected beings—to be motivated. -

6. Railton's “Alienation, Consequentialism, and the Demands of Morality”

6. Railton’s “Alienation, Consequentialism, and the Demands of Morality” Martín Abreu Zavaleta July 14, 2015 Railton is addressing one kind of problem that we raised. In class, we discussed the case of a parent who is offered a choice between saving the life of her own child or saving the life of another child. Saving the life of the other child would produce overall more utility than saving the life of her own, so utilitarian consequentialism claims that she should save the life of the other child. To many people, this seems to be the wrong result: surely, they think, whatever duty she has to save the life of the other child is overridden by her duties and obligations to save the life of her own child. Samuel Scheffler presents us with a less tragic, but related problem for consequentialism. Schef- fler observes that consequentialism demands that we don’t buy new shoes if we can spend that money in ways that will help other people more, or that we don’t watch TV if instead we could be doing more utility maximizing things. These two cases point to one important problem for consequentialism (here, under the guise of utilitarianism). Consequentialism seems to alienate us from the people we love and from things that make our lives richer. By focusing solely on the maximization of utility, it seems to ignore the value that other things bring into our lives: things like friendship, the love for one’s family, entertainment, art appreciation, etc. A life lived in line with consequentialist demands seems to be a very impoverished life, enslaved to the maximization of utility. -

Hedonism (For International Encyclopedia of Ethics)

Hedonism Word Count: 4,488 Hedonism is among the oldest, simplest, and most widely discussed theories of value – theories that tell us what makes the world better or what makes a person’s life go better. Hedonism, in a word, is the view that “pleasure is the good.” In its most comprehensive form, hedonism about value holds that the only thing that ultimately ever makes the world, or a life, better is its containing more pleasure or less pain. The term ‘hedonism’ is also sometimes used to refer to doctrines about other topics. ‘Universal hedonism’ sometimes stands for the view that we ought to bring the greatest balance of pleasure over pain into the world that we can (see UTILITARIANISM), and ‘psychological hedonism’ the view that all human behavior is motivated ultimately by desires to obtain pleasure or avoid pain. Our topic here is hedonism about value. 1. What is hedonism about value? a. What is hedonism a theory of? An important distinction among kinds of value is the distinction between something’s being good for some person (or other subject), and something’s simply being a good thing (see GOOD AND GOOD FOR). The former kind of value – called ‘welfare’ or ‘well-being’ – makes our lives better, or makes things go better for us (see WELL-BEING), while the latter kind of value makes the world better. Typically, whenever a person receives some benefit, or has his life made better, this also makes the world better. But it is at least conceivable that the two come apart, as when an undeserving person receives some benefit, making things go better for him 1 without perhaps making the world better. -

The Good Life: a Defense of Attitudinal Hedonism

from Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 65 (2002): 604-628 first presented at the Chisholm Memorial Conference Brown University, November 10, 2000 The Good Life: A Defense of Attitudinal Hedonism Fred Feldman University of Massachusetts, Amherst 1. The Good Life The students and colleagues of Roderick Chisholm admired and respected Chisholm. Many were filled not only with admiration, but with affection and gratitude for Chisholm throughout the time we knew him. Even now that he is dead, we continue to wish him well. Under the circumstances, many of us probably think that that wish amounts to no more than this: we hope that things went well for him when he lived; we hope that he had a good life. But reflection on this hope may lead some of us to ask a question: precisely what feature must Chisholm’s life have had in order for that life to have been a good one? What would have made his life one well worth living? On this question there is much puzzlement and many suggested answers. Nowadays one of the most popular answers is that a person’s life goes well if he gets what he wants.1 (Or perhaps that he gets what he really would have wanted if he had thought about it carefully.) According to a currently somewhat less popular answer, what makes a person’s life go well is that he enjoys what he gets. On this view, it does not matter essentially whether the person had any desire for the things he enjoyed prior to his receipt of them, nor does it matter whether he even would have had a desire for them if he had reflected on them. -

Origins of Dualism in Anglican Christianity

1 The Origins of Dualism in Anglican Christianity In analyzing Anglican Christianity one discovers that it possesses a fairly peculiar set of characteristics stemming from its formation. While it technically stems from the Protestant tradition, it nevertheless holds on to a very large number of much older Catholic tenants. One of these tenants, a sense of dualistic separation between the divine and the worldly, dates back to the medieval churches of England, and arguably even earlier. St. Augustine of Hippo, who with his City of God created a text arguably as influential to the creation of modern Christianity as the Bible itself, primarily constructed these beliefs. In it he takes a Neoplatonic worldview and Deleted: , who with his City of God created a text arguably as influential to the creation of modern Christianity as the Bible itself applies it to Christianity, separating heaven from earth akin to a “world of forms.” While we will Comment [JWG1]: This is unclear…you mean (I think) that he uses the premise of Plato’s world of forms to draw explore and demonstrate this incredibly important piece of history, my ultimate concern lies distinctions between the divine and the temporal. But your meaning is not obvious. beyond this. In studying Saxon poetry, one comes to ask himself if dualism arises in Anglican Comment [JWG2]: This shift to Saxon poetry is kinda abrupt. I think you might have been better off to ask the Christianity from St. Augustine alone, or if the pagan influences played a larger role in the question first (“is this sort of dualism only an Augustinian artifact, or can be blame the pagans, too?”) and then noted that if we look at poetry we find some surprising answers. -

DICTIONARY of PHILOSOPHY This Page Intentionally Left Blank

A DICTIONARY OF PHILOSOPHY This page intentionally left blank. A Dictionary of Philosophy Third edition A.R.Lacey Department of Philosophy, King’s College, University of London First published in 1976 by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd Second edition 1986 Third edition 1996 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” © A.R.Lacey 1976, 1986, 1996 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Lacey, A.R. A dictionary of philosophy.—3rd edn. 1. Philosophy—Dictionaries I. Title 190′.3′21 B41 ISBN 0-203-19819-0 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-19822-0 (Adobe eReader Format) ISBN 0-415-13332-7 (Print Edition) Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available on request Preface to the first edition This book aims to give the layman or intending student a pocket encyclopaedia of philosophy, one with a bias towards explaining terminology. The latter task is not an easy one since philosophy is regularly concerned with concepts which are unclear. -

Hedonism and Indian Philosophy of Peace: an Examination

IDEA – Studia nad strukturą i rozwojem pojęć filozoficznych XXIX/1 Białystok 2017 Aditya Kumar Gupta, Kanika Saraf (Delhi, Indie) HEDONISM AND INDIAN PHILOSOPHY OF PEACE: AN EXAMINATION Human being,like other animals,is a creature who desires pleasure and avoids pain.It is natural for a man to avail or allow only those moments which give pleasure to him and to go away from moments of pain. But despite being pleasure-loving, what do we get in the end?, Do we remain happy after we get pleasure?.Why is it so that a pleasure creates a type of boredom after some time which, later on, develops the desire for another or higher pleasures?What is the mystery of human life -we seek pleasure but remain unsatisfied even after we get it? The Proposed article is the critical study of hedonism in the light of Indian philosophy of Renunciation and Peace. The term ‘Hedonism’ comes from Latin term ‘ Hedone ’, which means pleas- ure. This is the philosophy which believes in pleasure as the aim of life and of any particular human action. Why do we do any particular task which is volun- tary in nature?; What do we want to get in the end? Hedonists answer these questions in one word- pleasure. Here by ‘pleasure’ they mean sensual pleasures which include even mental pleasure 1. There are six commonly accepted sense organs-Eyes, Ears, Nose, Skin, Tongue and Mind. Pleasure is always associated with these six sense organs. Hedonism is based on two assumptions,-a metaphysical and a psychologi- cal. According to Metaphysical assumption, self or mind is purely sensuous in nature, a series of sensations, feelings, appetites, and instincts. -

Egoism in Chinese Ethics

E Egoism in Chinese Ethics Kim-Chong CHONG The term “egoism,” wei wo, in Chinese ethics is usu- universalization and the maximization of self-interest. ally associated with Yang Zhu, but it encompasses is- Ethical egoism is therefore largely a heuristic device sues much wider than the narrow and overriding con- of the twentieth century, although the two criteria just ception of self-interest attributed to him by Mencius mentioned had precursors in Hobbes and Kant. (Mengzi): “Even if he could benefit the Empire by A. C. Graham (1989) recounts a dialogue in the pulling one hair he would not do it (Mencius 7A26).” Mozi between Wumazi and Mozi, which can illustrate These include questions about the possibility of uni- the issue of universalization, although we shall have versal love, the extension of benevolence, human na- to qualify this later. Wumazi claims to be incapable ture, the ultimate motivation for behavior, self-cultiva- of concern for everyone; he says that although he is tion, the value of spontaneity, and the conflict between concerned for the people of his own neighborhood, he particularistic concern—i.e., concern for one’s is by degrees more concerned for his family than for kin—and nonparticularistic concern. These related is- his neighbors, for his parents than for other members sues surround classical figures like Mozi, Yang Zhu, of his family, and ultimately for himself than for his Gaozi, Mencius, and, beyond them, the neo-Confu- parents. The issue for Mozi is whether this is a morality cians. that can be prescribed: “Are you going to hide your Before describing these issues, we should first mention egoism in western ethics, where it has often morality, or tell others about it?” To Wumazi’s re- been discussed in terms of ethical egoism and psycho- sponse that he will tell others, Mozi argues that Wu- logical egoism. -

Five Visions of Yang Zhu: Before He Became a Philosopher

DOI: 10.4312/as.2020.8.2.235-256 235 Five Visions of Yang Zhu: Before He Became a Philosopher Carine M. G. DEFOORT* Abstract This paper traces the consecutive emergence of five important portrayals of Yang Zhu before he became a philosopher in the Republic. In the late Zhou, he was portrayed as a rival in debate and a defender of physical or personal integrity. From the Han onward, he became part of a rhetorical trope based on Mencius’ portrayal. In the Wei Jin he was a prominent figure in his own right. The fourth portrayal, from the Song onward, contained reflections on his thought in the shadow of Mozi and Confucian orthodoxy. Finally, in the late Qing, Kang Youwei presented him as a minor political reformer responding to Confucius’ reform plans. These layers contributed in various ways to the nowadays al- most exclusive presentation of Yang Zhu as a philosopher, a defender of social tolerance, autonomy, or individual freedom. The rich variety of the portrayals has too often been sacrificed for this relatively homogeneous portrayal. Keywords: Yang Zhu, Mencius, Succession of the Way, Liezi, Neo-Confucianism, Kang Youwei Pet pogledov na Yang Zhuja preden je postal filozof Izvleček Članek sledi nastanku petih zaporednih pomembnih upodobitev Yang Zhuja, preden je v času republike postal filozof. V poznem obdobju dinastije Zhou so ga v razpravi upodab- ljali kot nasprotnika ter zaščitnika telesne in osebne integritete. Od dinastije Han naprej je postal del retorične figure, utemeljene na Mencijevi upodobitvi. V času dinastij Wei in Jin je veljal za pomembno zgodovinsko osebnost.