Computations of Binomial Ideals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discriminant Analysis

Chapter 5 Discriminant Analysis This chapter considers discriminant analysis: given p measurements w, we want to correctly classify w into one of G groups or populations. The max- imum likelihood, Bayesian, and Fisher’s discriminant rules are used to show why methods like linear and quadratic discriminant analysis can work well for a wide variety of group distributions. 5.1 Introduction Definition 5.1. In supervised classification, there are G known groups and m test cases to be classified. Each test case is assigned to exactly one group based on its measurements wi. Suppose there are G populations or groups or classes where G 2. Assume ≥ that for each population there is a probability density function (pdf) fj(z) where z is a p 1 vector and j =1,...,G. Hence if the random vector x comes × from population j, then x has pdf fj (z). Assume that there is a random sam- ple of nj cases x1,j,..., xnj ,j for each group. Let (xj , Sj ) denote the sample mean and covariance matrix for each group. Let wi be a new p 1 (observed) random vector from one of the G groups, but the group is unknown.× Usually there are many wi, and discriminant analysis (DA) or classification attempts to allocate the wi to the correct groups. The w1,..., wm are known as the test data. Let πk = the (prior) probability that a randomly selected case wi belongs to the kth group. If x1,1..., xnG,G are a random sample of cases from G the collection of G populations, thenπ ˆk = nk/n where n = i=1 ni. -

Solving Quadratic Equations by Factoring

5.2 Solving Quadratic Equations by Factoring Goals p Factor quadratic expressions and solve quadratic equations by factoring. p Find zeros of quadratic functions. Your Notes VOCABULARY Binomial An expression with two terms, such as x ϩ 1 Trinomial An expression with three terms, such as x2 ϩ x ϩ 1 Factoring A process used to write a polynomial as a product of other polynomials having equal or lesser degree Monomial An expression with one term, such as 3x Quadratic equation in one variable An equation that can be written in the form ax2 ϩ bx ϩ c ϭ 0 where a 0 Zero of a function A number k is a zero of a function f if f(k) ϭ 0. Example 1 Factoring a Trinomial of the Form x2 ؉ bx ؉ c Factor x2 Ϫ 9x ϩ 14. Solution You want x2 Ϫ 9x ϩ 14 ϭ (x ϩ m)(x ϩ n) where mn ϭ 14 and m ϩ n ϭ Ϫ9 . Factors of 14 1, Ϫ1, Ϫ 2, Ϫ2, Ϫ (m, n) 14 14 7 7 Sum of factors Ϫ Ϫ m ؉ n) 15 15 9 9) The table shows that m ϭ Ϫ2 and n ϭ Ϫ7 . So, x2 Ϫ 9x ϩ 14 ϭ ( x Ϫ 2 )( x Ϫ 7 ). Lesson 5.2 • Algebra 2 Notetaking Guide 97 Your Notes Example 2 Factoring a Trinomial of the Form ax2 ؉ bx ؉ c Factor 2x2 ϩ 13x ϩ 6. Solution You want 2x2 ϩ 13x ϩ 6 ϭ (kx ϩ m)(lx ϩ n) where k and l are factors of 2 and m and n are ( positive ) factors of 6 . -

Alicia Dickenstein

A WORLD OF BINOMIALS ——————————– ALICIA DICKENSTEIN Universidad de Buenos Aires FOCM 2008, Hong Kong - June 21, 2008 A. Dickenstein - FoCM 2008, Hong Kong – p.1/39 ORIGINAL PLAN OF THE TALK BASICS ON BINOMIALS A. Dickenstein - FoCM 2008, Hong Kong – p.2/39 ORIGINAL PLAN OF THE TALK BASICS ON BINOMIALS COUNTING SOLUTIONS TO BINOMIAL SYSTEMS A. Dickenstein - FoCM 2008, Hong Kong – p.2/39 ORIGINAL PLAN OF THE TALK BASICS ON BINOMIALS COUNTING SOLUTIONS TO BINOMIAL SYSTEMS DISCRIMINANTS (DUALS OF BINOMIAL VARIETIES) A. Dickenstein - FoCM 2008, Hong Kong – p.2/39 ORIGINAL PLAN OF THE TALK BASICS ON BINOMIALS COUNTING SOLUTIONS TO BINOMIAL SYSTEMS DISCRIMINANTS (DUALS OF BINOMIAL VARIETIES) BINOMIALS AND RECURRENCE OF HYPERGEOMETRIC COEFFICIENTS A. Dickenstein - FoCM 2008, Hong Kong – p.2/39 ORIGINAL PLAN OF THE TALK BASICS ON BINOMIALS COUNTING SOLUTIONS TO BINOMIAL SYSTEMS DISCRIMINANTS (DUALS OF BINOMIAL VARIETIES) BINOMIALS AND RECURRENCE OF HYPERGEOMETRIC COEFFICIENTS BINOMIALS AND MASS ACTION KINETICS DYNAMICS A. Dickenstein - FoCM 2008, Hong Kong – p.2/39 RESCHEDULED PLAN OF THE TALK BASICS ON BINOMIALS - How binomials “sit” in the polynomial world and the main “secrets” about binomials A. Dickenstein - FoCM 2008, Hong Kong – p.3/39 RESCHEDULED PLAN OF THE TALK BASICS ON BINOMIALS - How binomials “sit” in the polynomial world and the main “secrets” about binomials COUNTING SOLUTIONS TO BINOMIAL SYSTEMS - with a touch of complexity A. Dickenstein - FoCM 2008, Hong Kong – p.3/39 RESCHEDULED PLAN OF THE TALK BASICS ON BINOMIALS - How binomials “sit” in the polynomial world and the main “secrets” about binomials COUNTING SOLUTIONS TO BINOMIAL SYSTEMS - with a touch of complexity (Mixed) DISCRIMINANTS (DUALS OF BINOMIAL VARIETIES) and an application to real roots A. -

The Diamond Method of Factoring a Quadratic Equation

The Diamond Method of Factoring a Quadratic Equation Important: Remember that the first step in any factoring is to look at each term and factor out the greatest common factor. For example: 3x2 + 6x + 12 = 3(x2 + 2x + 4) AND 5x2 + 10x = 5x(x + 2) If the leading coefficient is negative, always factor out the negative. For example: -2x2 - x + 1 = -1(2x2 + x - 1) = -(2x2 + x - 1) Using the Diamond Method: Example 1 2 Factor 2x + 11x + 15 using the Diamond Method. +30 Step 1: Multiply the coefficient of the x2 term (+2) and the constant (+15) and place this product (+30) in the top quarter of a large “X.” Step 2: Place the coefficient of the middle term in the bottom quarter of the +11 “X.” (+11) Step 3: List all factors of the number in the top quarter of the “X.” +30 (+1)(+30) (-1)(-30) (+2)(+15) (-2)(-15) (+3)(+10) (-3)(-10) (+5)(+6) (-5)(-6) +30 Step 4: Identify the two factors whose sum gives the number in the bottom quarter of the “x.” (5 ∙ 6 = 30 and 5 + 6 = 11) and place these factors in +5 +6 the left and right quarters of the “X” (order is not important). +11 Step 5: Break the middle term of the original trinomial into the sum of two terms formed using the right and left quarters of the “X.” That is, write the first term of the original equation, 2x2 , then write 11x as + 5x + 6x (the num bers from the “X”), and finally write the last term of the original equation, +15 , to get the following 4-term polynomial: 2x2 + 11x + 15 = 2x2 + 5x + 6x + 15 Step 6: Factor by Grouping: Group the first two terms together and the last two terms together. -

Factoring Polynomials

2/13/2013 Chapter 13 § 13.1 Factoring The Greatest Common Polynomials Factor Chapter Sections Factors 13.1 – The Greatest Common Factor Factors (either numbers or polynomials) 13.2 – Factoring Trinomials of the Form x2 + bx + c When an integer is written as a product of 13.3 – Factoring Trinomials of the Form ax 2 + bx + c integers, each of the integers in the product is a factor of the original number. 13.4 – Factoring Trinomials of the Form x2 + bx + c When a polynomial is written as a product of by Grouping polynomials, each of the polynomials in the 13.5 – Factoring Perfect Square Trinomials and product is a factor of the original polynomial. Difference of Two Squares Factoring – writing a polynomial as a product of 13.6 – Solving Quadratic Equations by Factoring polynomials. 13.7 – Quadratic Equations and Problem Solving Martin-Gay, Developmental Mathematics 2 Martin-Gay, Developmental Mathematics 4 1 2/13/2013 Greatest Common Factor Greatest Common Factor Greatest common factor – largest quantity that is a Example factor of all the integers or polynomials involved. Find the GCF of each list of numbers. 1) 6, 8 and 46 6 = 2 · 3 Finding the GCF of a List of Integers or Terms 8 = 2 · 2 · 2 1) Prime factor the numbers. 46 = 2 · 23 2) Identify common prime factors. So the GCF is 2. 3) Take the product of all common prime factors. 2) 144, 256 and 300 144 = 2 · 2 · 2 · 3 · 3 • If there are no common prime factors, GCF is 1. 256 = 2 · 2 · 2 · 2 · 2 · 2 · 2 · 2 300 = 2 · 2 · 3 · 5 · 5 So the GCF is 2 · 2 = 4. -

Factoring Polynomials

EAP/GWL Rev. 1/2011 Page 1 of 5 Factoring a polynomial is the process of writing it as the product of two or more polynomial factors. Example: — Set the factors of a polynomial equation (as opposed to an expression) equal to zero in order to solve for a variable: Example: To solve ,; , The flowchart below illustrates a sequence of steps for factoring polynomials. First, always factor out the Greatest Common Factor (GCF), if one exists. Is the equation a Binomial or a Trinomial? 1 Prime polynomials cannot be factored Yes No using integers alone. The Sum of Squares and the Four or more quadratic factors Special Cases? terms of the Sum and Difference of Binomial Trinomial Squares are (two terms) (three terms) Factor by Grouping: always Prime. 1. Group the terms with common factors and factor 1. Difference of Squares: out the GCF from each Perfe ct Square grouping. 1 , 3 Trinomial: 2. Sum of Squares: 1. 2. Continue factoring—by looking for Special Cases, 1 , 2 2. 3. Difference of Cubes: Grouping, etc.—until the 3 equation is in simplest form FYI: A Sum of Squares can 1 , 2 (or all factors are Prime). 4. Sum of Cubes: be factored using imaginary numbers if you rewrite it as a Difference of Squares: — 2 Use S.O.A.P to No Special √1 √1 Cases remember the signs for the factors of the 4 Completing the Square and the Quadratic Formula Sum and Difference Choose: of Cubes: are primarily methods for solving equations rather 1. Factor by Grouping than simply factoring expressions. -

A Saturation Algorithm for Homogeneous Binomial Ideals

A Saturation Algorithm for Homogeneous Binomial Ideals Deepanjan Kesh and Shashank K Mehta Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur - 208016, India, fdeepkesh,[email protected] Abstract. Let k[x1; : : : ; xn] be a polynomial ring in n variables, and let I ⊂ k[x1; : : : ; xn] be a homogeneous binomial ideal. We describe a fast 1 algorithm to compute the saturation, I :(x1 ··· xn) . In the special case when I is a toric ideal, we present some preliminary results comparing our algorithm with Project and Lift by Hemmecke and Malkin. 1 Introduction 1.1 Problem Description Let k[x1; : : : ; xn] be a polynomial ring in n variables over the field k, and let I ⊂ k[x1; : : : ; xn] be an ideal. Ideals are said to be homogeneous, if they have a basis consisting of homogeneous polynomials. Binomials in this ring are defined as polynomials with at most two terms [5]. Thus, a binomial is a polynomial of the form cxα+dxβ, where c; d are arbitrary coefficients. Pure difference binomials are special cases of binomials of the form xα − xβ. Ideals with a binomial basis are called binomial ideals. Toric ideals, the kernel of a specific kind of polynomial ring homomorphisms, are examples of pure difference binomial ideals. Saturation of an ideal, I, by a polynomial f, denoted by I : f, is defined as the ideal I : f = hf g 2 k[x1; : : : ; xn]: f · g 2 I gi: Similarly, I : f 1 is defined as 1 a I : f = hf g 2 k[x1; : : : ; xn]: 9a 2 N; f · g 2 I gi: 1 We describe a fast algorithm to compute the saturation, I :(x1 ··· xn) , of a homogeneous binomial ideal I. -

CYCLIC RESULTANTS 1. Introduction the M-Th Cyclic Resultant of A

CYCLIC RESULTANTS CHRISTOPHER J. HILLAR Abstract. We characterize polynomials having the same set of nonzero cyclic resultants. Generically, for a polynomial f of degree d, there are exactly 2d−1 distinct degree d polynomials with the same set of cyclic resultants as f. How- ever, in the generic monic case, degree d polynomials are uniquely determined by their cyclic resultants. Moreover, two reciprocal (\palindromic") polyno- mials giving rise to the same set of nonzero cyclic resultants are equal. In the process, we also prove a unique factorization result in semigroup algebras involving products of binomials. Finally, we discuss how our results yield algo- rithms for explicit reconstruction of polynomials from their cyclic resultants. 1. Introduction The m-th cyclic resultant of a univariate polynomial f 2 C[x] is m rm = Res(f; x − 1): We are primarily interested here in the fibers of the map r : C[x] ! CN given by 1 f 7! (rm)m=0. In particular, what are the conditions for two polynomials to give rise to the same set of cyclic resultants? For technical reasons, we will only consider polynomials f that do not have a root of unity as a zero. With this restriction, a polynomial will map to a set of all nonzero cyclic resultants. Our main result gives a complete answer to this question. Theorem 1.1. Let f and g be polynomials in C[x]. Then, f and g generate the same sequence of nonzero cyclic resultants if and only if there exist u; v 2 C[x] with u(0) 6= 0 and nonnegative integers l1; l2 such that deg(u) ≡ l2 − l1 (mod 2), and f(x) = (−1)l2−l1 xl1 v(x)u(x−1)xdeg(u) g(x) = xl2 v(x)u(x): Remark 1.2. -

6 Multiplying a Binomial by a Monomial

Looking 4 Ahead Multiplying a Binomial by a Monomial Then Why? You have already A square patio has a side length of x meters. multiplied monomials. If you increase the length by 3 meters, what (Lesson 9-3) is the area of the new patio? x Now a. Write an expression to represent the new side Use models to multiply length of the patio. a binomial by a x monomial. b. Write an expression to represent the area of the 3m new patio. Multiply a binomial by a monomial to solve equations. Binomials You can use algebra tiles to model binomials, a polynomial with New Vocabulary two terms. binomal The algebra tiles shown form a rectangle with a width of x and a length of x + 2. They represent the product x(x + 2). Math Online x 11 glencoe.com 2 x Y YY The area of the rectangle represents the product. Since the rectangle consists of one x 2 -tile and two x-tiles, x(x + 2) = x 2 + 2x. EXAMPLE 1 Multiplying a Binomial by a Monomial Use algebra tiles to find x(x + 3). Step 1 Make a rectangle with a width x 111 of x and a length of x + 3. Use algebra tiles to mark off the dimensions on a product mat. x Step 2 Using the marks as a guide, fill in the rectangle with algebra tiles. x 111 2 Step 3 The area of the rectangle is x Y YYY x 2 + x + x + x. In simplest form, the area is x 2 + 3x. -

Factoring Middle Binomial Coefficients Gennady Eremin [email protected] March 5, 2020

Factoring Middle Binomial Coefficients Gennady Eremin [email protected] March 5, 2020 Abstract. The article describes prime intervals into the prime factorization of middle binomial coefficient. Prime factors and prime powers are distributed in layers. Each layer consists of non-repeated prime numbers which are chosen (not calculated) from the noncrossing prime intervals. Repeated factors are formed when primes are duplicated among different layers. Key Words: Prime factorization, middle binomial coefficient, Chebyshev interval, Kummer’s theorem, Legendre layer. 1. Introduction 1.1. Chebyshev intervals. This article arose thanks to the paper of Pomerance [1] that deals with the middle binomial coefficient (MBC) B (n) = ( ). These co- efficients are located in the center of the even-numbered rows of Pascal’s triangle. The author notes that ( ) is divisible by the product of all primes in the interval (n, 2n). This fact was considered by Chebyshev still in 1850, and we will show that a similar prime interval (or the Chebyshev interval) is not the only one in the prime factorization of B (n). MBC’s belong to the family of Catalan-like numbers, such as Catalan numbers, Motzkin numbers, hexagonal numbers, etc. The MBC is the crucial character in the definition of the Catalan number C (n) = B (n) / (n+1). In [2] the prime factorization of Catalan numbers is carried out using the iden- tical Chebyshev intervals. We will apply use same techniques and methods in this paper. For the MBC the general term is 2 ⧸ (1.1) B (n) = (2n)! (n!) , n ≥ 0. The first coefficients are 1, 2, 6, 20, 70, 252, 924, 3432, … (sequence A000984). -

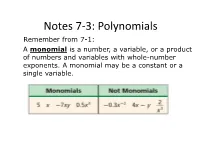

Polynomials Remember from 7-1: a Monomial Is a Number, a Variable, Or a Product of Numbers and Variables with Whole-Number Exponents

Notes 7-3: Polynomials Remember from 7-1: A monomial is a number, a variable, or a product of numbers and variables with whole-number exponents. A monomial may be a constant or a single variable. I. Identifying Polynomials A polynomial is a monomial or a sum or difference of monomials. Some polynomials have special names. A binomial is the sum of two monomials. A trinomial is the sum of three monomials. • Example: State whether the expression is a polynomial. If it is a polynomial, identify it as a monomial, binomial, or trinomial. Expression Polynomial? Monomial, Binomial, or Trinomial? 2x - 3yz Yes, 2x - 3yz = 2x + (-3yz), the binomial sum of two monomials 8n3+5n-2 No, 5n-2 has a negative None of these exponent, so it is not a monomial -8 Yes, -8 is a real number Monomial 4a2 + 5a + a + 9 Yes, the expression simplifies Monomial to 4a2 + 6a + 9, so it is the sum of three monomials II. Degrees and Leading Coefficients The terms of a polynomial are the monomials that are being added or subtracted. The degree of a polynomial is the degree of the term with the greatest degree. The leading coefficient is the coefficient of the variable with the highest degree. Find the degree and leading coefficient of each polynomial Polynomial Terms Degree Leading Coefficient 5n2 5n 2 2 5 -4x3 + 3x2 + 5 -4x2, 3x2, 3 -4 5 -a4-1 -a4, -1 4 -1 III. Ordering the terms of a polynomial The terms of a polynomial may be written in any order. However, the terms of a polynomial are usually arranged so that the powers of one variable are in descending (decreasing, large to small) order. -

Determine Whether Each Expression Is a Polynomial

8-1 Adding and Subtracting Polynomials Determine whether each expression is a polynomial. If it is a polynomial, find the degree and determine whether it is a monomial, binomial, or trinomial. 2 3 1. 7ab + 6b – 2a ANSWER: yes; 3; trinomial 2. 2y – 5 + 3y2 ANSWER: yes; 2; trinomial 2 3. 3x ANSWER: yes; 2; monomial 4. ANSWER: No; a monomial cannot have a variable in the denominator. 5. 5m2p 3 + 6 ANSWER: yes; 5; binomial –4 6. 5q + 6q ANSWER: No; , and a monomial cannot have a variable in the denominator. Write each polynomial in standard form. Identify the leading coefficient. 7. –4d4 + 1 – d2 ANSWER: 4 2 –4d – d + 1; –4 8. 2x5 – 12 + 3x ANSWER: 5 2x + 3x – 12 ; 2 9. 4z – 2z2 – 5z4 eSolutionsANSWER: Manual - Powered by Cognero Page 1 4 2 –5z – 2z + 4z; –5 10. 2a + 4a3 – 5a2 – 1 ANSWER: 3 2 4a – 5a + 2a – 1, 4 Find each sum or difference. 11. (6x3 − 4) + (−2x3 + 9) ANSWER: 3 4x + 5 12. (g3 − 2g2 + 5g + 6) − (g2 + 2g) ANSWER: 3 2 g − 3g + 3g + 6 13. (4 + 2a2 − 2a) − (3a2 − 8a + 7) ANSWER: 2 −a + 6a − 3 14. (8y − 4y2) + (3y − 9y2) ANSWER: 2 −13y + 11y 15. (−4z3 − 2z + 8) − (4z3 + 3z2 − 5) ANSWER: 3 2 −8z − 3z − 2z + 13 16. (−3d2 − 8 + 2d) + (4d − 12 + d2) ANSWER: 2 −2d + 6d − 20 17. (y + 5) + (2y + 4y2 – 2) ANSWER: 2 4y + 3y + 3 18. (3n3 − 5n + n2) − (−8n2 + 3n3) ANSWER: 2 9n − 5n 19. CCSS SENSE-MAKING The total number of students T who traveled for spring break consists of two groups: students who flew to their destinations F and students who drove to their destination D.