The Diamond Method of Factoring a Quadratic Equation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discriminant Analysis

Chapter 5 Discriminant Analysis This chapter considers discriminant analysis: given p measurements w, we want to correctly classify w into one of G groups or populations. The max- imum likelihood, Bayesian, and Fisher’s discriminant rules are used to show why methods like linear and quadratic discriminant analysis can work well for a wide variety of group distributions. 5.1 Introduction Definition 5.1. In supervised classification, there are G known groups and m test cases to be classified. Each test case is assigned to exactly one group based on its measurements wi. Suppose there are G populations or groups or classes where G 2. Assume ≥ that for each population there is a probability density function (pdf) fj(z) where z is a p 1 vector and j =1,...,G. Hence if the random vector x comes × from population j, then x has pdf fj (z). Assume that there is a random sam- ple of nj cases x1,j,..., xnj ,j for each group. Let (xj , Sj ) denote the sample mean and covariance matrix for each group. Let wi be a new p 1 (observed) random vector from one of the G groups, but the group is unknown.× Usually there are many wi, and discriminant analysis (DA) or classification attempts to allocate the wi to the correct groups. The w1,..., wm are known as the test data. Let πk = the (prior) probability that a randomly selected case wi belongs to the kth group. If x1,1..., xnG,G are a random sample of cases from G the collection of G populations, thenπ ˆk = nk/n where n = i=1 ni. -

Solving Quadratic Equations by Factoring

5.2 Solving Quadratic Equations by Factoring Goals p Factor quadratic expressions and solve quadratic equations by factoring. p Find zeros of quadratic functions. Your Notes VOCABULARY Binomial An expression with two terms, such as x ϩ 1 Trinomial An expression with three terms, such as x2 ϩ x ϩ 1 Factoring A process used to write a polynomial as a product of other polynomials having equal or lesser degree Monomial An expression with one term, such as 3x Quadratic equation in one variable An equation that can be written in the form ax2 ϩ bx ϩ c ϭ 0 where a 0 Zero of a function A number k is a zero of a function f if f(k) ϭ 0. Example 1 Factoring a Trinomial of the Form x2 ؉ bx ؉ c Factor x2 Ϫ 9x ϩ 14. Solution You want x2 Ϫ 9x ϩ 14 ϭ (x ϩ m)(x ϩ n) where mn ϭ 14 and m ϩ n ϭ Ϫ9 . Factors of 14 1, Ϫ1, Ϫ 2, Ϫ2, Ϫ (m, n) 14 14 7 7 Sum of factors Ϫ Ϫ m ؉ n) 15 15 9 9) The table shows that m ϭ Ϫ2 and n ϭ Ϫ7 . So, x2 Ϫ 9x ϩ 14 ϭ ( x Ϫ 2 )( x Ϫ 7 ). Lesson 5.2 • Algebra 2 Notetaking Guide 97 Your Notes Example 2 Factoring a Trinomial of the Form ax2 ؉ bx ؉ c Factor 2x2 ϩ 13x ϩ 6. Solution You want 2x2 ϩ 13x ϩ 6 ϭ (kx ϩ m)(lx ϩ n) where k and l are factors of 2 and m and n are ( positive ) factors of 6 . -

Alicia Dickenstein

A WORLD OF BINOMIALS ——————————– ALICIA DICKENSTEIN Universidad de Buenos Aires FOCM 2008, Hong Kong - June 21, 2008 A. Dickenstein - FoCM 2008, Hong Kong – p.1/39 ORIGINAL PLAN OF THE TALK BASICS ON BINOMIALS A. Dickenstein - FoCM 2008, Hong Kong – p.2/39 ORIGINAL PLAN OF THE TALK BASICS ON BINOMIALS COUNTING SOLUTIONS TO BINOMIAL SYSTEMS A. Dickenstein - FoCM 2008, Hong Kong – p.2/39 ORIGINAL PLAN OF THE TALK BASICS ON BINOMIALS COUNTING SOLUTIONS TO BINOMIAL SYSTEMS DISCRIMINANTS (DUALS OF BINOMIAL VARIETIES) A. Dickenstein - FoCM 2008, Hong Kong – p.2/39 ORIGINAL PLAN OF THE TALK BASICS ON BINOMIALS COUNTING SOLUTIONS TO BINOMIAL SYSTEMS DISCRIMINANTS (DUALS OF BINOMIAL VARIETIES) BINOMIALS AND RECURRENCE OF HYPERGEOMETRIC COEFFICIENTS A. Dickenstein - FoCM 2008, Hong Kong – p.2/39 ORIGINAL PLAN OF THE TALK BASICS ON BINOMIALS COUNTING SOLUTIONS TO BINOMIAL SYSTEMS DISCRIMINANTS (DUALS OF BINOMIAL VARIETIES) BINOMIALS AND RECURRENCE OF HYPERGEOMETRIC COEFFICIENTS BINOMIALS AND MASS ACTION KINETICS DYNAMICS A. Dickenstein - FoCM 2008, Hong Kong – p.2/39 RESCHEDULED PLAN OF THE TALK BASICS ON BINOMIALS - How binomials “sit” in the polynomial world and the main “secrets” about binomials A. Dickenstein - FoCM 2008, Hong Kong – p.3/39 RESCHEDULED PLAN OF THE TALK BASICS ON BINOMIALS - How binomials “sit” in the polynomial world and the main “secrets” about binomials COUNTING SOLUTIONS TO BINOMIAL SYSTEMS - with a touch of complexity A. Dickenstein - FoCM 2008, Hong Kong – p.3/39 RESCHEDULED PLAN OF THE TALK BASICS ON BINOMIALS - How binomials “sit” in the polynomial world and the main “secrets” about binomials COUNTING SOLUTIONS TO BINOMIAL SYSTEMS - with a touch of complexity (Mixed) DISCRIMINANTS (DUALS OF BINOMIAL VARIETIES) and an application to real roots A. -

Solving Cubic Polynomials

Solving Cubic Polynomials 1.1 The general solution to the quadratic equation There are four steps to finding the zeroes of a quadratic polynomial. 1. First divide by the leading term, making the polynomial monic. a 2. Then, given x2 + a x + a , substitute x = y − 1 to obtain an equation without the linear term. 1 0 2 (This is the \depressed" equation.) 3. Solve then for y as a square root. (Remember to use both signs of the square root.) a 4. Once this is done, recover x using the fact that x = y − 1 . 2 For example, let's solve 2x2 + 7x − 15 = 0: First, we divide both sides by 2 to create an equation with leading term equal to one: 7 15 x2 + x − = 0: 2 2 a 7 Then replace x by x = y − 1 = y − to obtain: 2 4 169 y2 = 16 Solve for y: 13 13 y = or − 4 4 Then, solving back for x, we have 3 x = or − 5: 2 This method is equivalent to \completing the square" and is the steps taken in developing the much- memorized quadratic formula. For example, if the original equation is our \high school quadratic" ax2 + bx + c = 0 then the first step creates the equation b c x2 + x + = 0: a a b We then write x = y − and obtain, after simplifying, 2a b2 − 4ac y2 − = 0 4a2 so that p b2 − 4ac y = ± 2a and so p b b2 − 4ac x = − ± : 2a 2a 1 The solutions to this quadratic depend heavily on the value of b2 − 4ac. -

Factoring Polynomials

2/13/2013 Chapter 13 § 13.1 Factoring The Greatest Common Polynomials Factor Chapter Sections Factors 13.1 – The Greatest Common Factor Factors (either numbers or polynomials) 13.2 – Factoring Trinomials of the Form x2 + bx + c When an integer is written as a product of 13.3 – Factoring Trinomials of the Form ax 2 + bx + c integers, each of the integers in the product is a factor of the original number. 13.4 – Factoring Trinomials of the Form x2 + bx + c When a polynomial is written as a product of by Grouping polynomials, each of the polynomials in the 13.5 – Factoring Perfect Square Trinomials and product is a factor of the original polynomial. Difference of Two Squares Factoring – writing a polynomial as a product of 13.6 – Solving Quadratic Equations by Factoring polynomials. 13.7 – Quadratic Equations and Problem Solving Martin-Gay, Developmental Mathematics 2 Martin-Gay, Developmental Mathematics 4 1 2/13/2013 Greatest Common Factor Greatest Common Factor Greatest common factor – largest quantity that is a Example factor of all the integers or polynomials involved. Find the GCF of each list of numbers. 1) 6, 8 and 46 6 = 2 · 3 Finding the GCF of a List of Integers or Terms 8 = 2 · 2 · 2 1) Prime factor the numbers. 46 = 2 · 23 2) Identify common prime factors. So the GCF is 2. 3) Take the product of all common prime factors. 2) 144, 256 and 300 144 = 2 · 2 · 2 · 3 · 3 • If there are no common prime factors, GCF is 1. 256 = 2 · 2 · 2 · 2 · 2 · 2 · 2 · 2 300 = 2 · 2 · 3 · 5 · 5 So the GCF is 2 · 2 = 4. -

Factoring Polynomials

EAP/GWL Rev. 1/2011 Page 1 of 5 Factoring a polynomial is the process of writing it as the product of two or more polynomial factors. Example: — Set the factors of a polynomial equation (as opposed to an expression) equal to zero in order to solve for a variable: Example: To solve ,; , The flowchart below illustrates a sequence of steps for factoring polynomials. First, always factor out the Greatest Common Factor (GCF), if one exists. Is the equation a Binomial or a Trinomial? 1 Prime polynomials cannot be factored Yes No using integers alone. The Sum of Squares and the Four or more quadratic factors Special Cases? terms of the Sum and Difference of Binomial Trinomial Squares are (two terms) (three terms) Factor by Grouping: always Prime. 1. Group the terms with common factors and factor 1. Difference of Squares: out the GCF from each Perfe ct Square grouping. 1 , 3 Trinomial: 2. Sum of Squares: 1. 2. Continue factoring—by looking for Special Cases, 1 , 2 2. 3. Difference of Cubes: Grouping, etc.—until the 3 equation is in simplest form FYI: A Sum of Squares can 1 , 2 (or all factors are Prime). 4. Sum of Cubes: be factored using imaginary numbers if you rewrite it as a Difference of Squares: — 2 Use S.O.A.P to No Special √1 √1 Cases remember the signs for the factors of the 4 Completing the Square and the Quadratic Formula Sum and Difference Choose: of Cubes: are primarily methods for solving equations rather 1. Factor by Grouping than simply factoring expressions. -

Math: Honors Geometry UNIT/Weeks (Not Timeline/Topics Essential Questions Consecutive)

Math: Honors Geometry UNIT/Weeks (not Timeline/Topics Essential Questions consecutive) Reasoning and Proof How can you make a Patterns and Inductive Reasoning conjecture and prove that it is Conditional Statements 2 true? Biconditionals Deductive Reasoning Reasoning in Algebra and Geometry Proving Angles Congruent Congruent Triangles How do you identify Congruent Figures corresponding parts of Triangle Congruence by SSS and SAS congruent triangles? Triangle Congruence by ASA and AAS How do you show that two 3 Using Corresponding Parts of Congruent triangles are congruent? Triangles How can you tell whether a Isosceles and Equilateral Triangles triangle is isosceles or Congruence in Right Triangles equilateral? Congruence in Overlapping Triangles Relationships Within Triangles Mid segments of Triangles How do you use coordinate Perpendicular and Angle Bisectors geometry to find relationships Bisectors in Triangles within triangles? 3 Medians and Altitudes How do you solve problems Indirect Proof that involve measurements of Inequalities in One Triangle triangles? Inequalities in Two Triangles How do you write indirect proofs? Polygons and Quadrilaterals How can you find the sum of The Polygon Angle-Sum Theorems the measures of polygon Properties of Parallelograms angles? Proving that a Quadrilateral is a Parallelogram How can you classify 3.2 Properties of Rhombuses, Rectangles and quadrilaterals? Squares How can you use coordinate Conditions for Rhombuses, Rectangles and geometry to prove general Squares -

Quadratic Equations Through History

Cal McKeever & Robert Bettinger COMMON CORE STANDARD 3B Choose and produce an equivalent form of an expression to reveal and explain properties of the quantity represented by the expression. Factor a quadratic expression to reveal the zeros of the function it defines. Complete the square in a quadratic expression to reveal the maximum or minimum value of the function it defines. SYNOPSIS At a summit of time-traveling historical mathematicians, attendees from Ancient Babylon pose the question of how to solve quadratic equations. Their method of completing the square serves their purposes, but there was far more to be done with this complex equation. Pythagoras, Euclid, Brahmagupta, Bhaskara II, Al-Khwarizmi and Descartes join the discussion, each pointing out their contributions to the contemporary understanding of solving quadratics through the quadratic formula. Through their discussion, the historical situation through which we understand the solving of quadratic equations is highlighted, showing the complex history of this formula taught everywhere. As the target audience for this project is high school students, the different characters of the script use language and symbolism that is anachronistic but will help the the students to understand the concepts that are discussed. For example, Diophantus did not use a,b,c in his actual texts but his fictional character in the the given script does explain his method of solving quadratics using contemporary notation. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The problem of solving quadratic equations dates back to Babylonia in the 2nd Millennium BC. The Babylonian understanding of quadratics was used geometrically, to solve questions of area with real-world solutions. -

Quadratic Polynomials

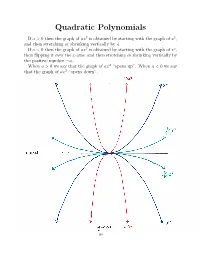

Quadratic Polynomials If a>0thenthegraphofax2 is obtained by starting with the graph of x2, and then stretching or shrinking vertically by a. If a<0thenthegraphofax2 is obtained by starting with the graph of x2, then flipping it over the x-axis, and then stretching or shrinking vertically by the positive number a. When a>0wesaythatthegraphof− ax2 “opens up”. When a<0wesay that the graph of ax2 “opens down”. I Cit i-a x-ax~S ~12 *************‘s-aXiS —10.? 148 2 If a, c, d and a = 0, then the graph of a(x + c) 2 + d is obtained by If a, c, d R and a = 0, then the graph of a(x + c)2 + d is obtained by 2 R 6 2 shiftingIf a, c, the d ⇥ graphR and ofaax=⇤ 2 0,horizontally then the graph by c, and of a vertically(x + c) + byd dis. obtained (Remember by shiftingshifting the the⇥ graph graph of of axax⇤ 2 horizontallyhorizontally by by cc,, and and vertically vertically by by dd.. (Remember (Remember thatthatd>d>0meansmovingup,0meansmovingup,d<d<0meansmovingdown,0meansmovingdown,c>c>0meansmoving0meansmoving thatleft,andd>c<0meansmovingup,0meansmovingd<right0meansmovingdown,.) c>0meansmoving leftleft,and,andc<c<0meansmoving0meansmovingrightright.).) 2 If a =0,thegraphofafunctionf(x)=a(x + c) 2+ d is called a parabola. If a =0,thegraphofafunctionf(x)=a(x + c)2 + d is called a parabola. 6 2 TheIf a point=0,thegraphofafunction⇤ ( c, d) 2 is called thefvertex(x)=aof(x the+ c parabola.) + d is called a parabola. The point⇤ ( c, d) R2 is called the vertex of the parabola. -

A Saturation Algorithm for Homogeneous Binomial Ideals

A Saturation Algorithm for Homogeneous Binomial Ideals Deepanjan Kesh and Shashank K Mehta Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur - 208016, India, fdeepkesh,[email protected] Abstract. Let k[x1; : : : ; xn] be a polynomial ring in n variables, and let I ⊂ k[x1; : : : ; xn] be a homogeneous binomial ideal. We describe a fast 1 algorithm to compute the saturation, I :(x1 ··· xn) . In the special case when I is a toric ideal, we present some preliminary results comparing our algorithm with Project and Lift by Hemmecke and Malkin. 1 Introduction 1.1 Problem Description Let k[x1; : : : ; xn] be a polynomial ring in n variables over the field k, and let I ⊂ k[x1; : : : ; xn] be an ideal. Ideals are said to be homogeneous, if they have a basis consisting of homogeneous polynomials. Binomials in this ring are defined as polynomials with at most two terms [5]. Thus, a binomial is a polynomial of the form cxα+dxβ, where c; d are arbitrary coefficients. Pure difference binomials are special cases of binomials of the form xα − xβ. Ideals with a binomial basis are called binomial ideals. Toric ideals, the kernel of a specific kind of polynomial ring homomorphisms, are examples of pure difference binomial ideals. Saturation of an ideal, I, by a polynomial f, denoted by I : f, is defined as the ideal I : f = hf g 2 k[x1; : : : ; xn]: f · g 2 I gi: Similarly, I : f 1 is defined as 1 a I : f = hf g 2 k[x1; : : : ; xn]: 9a 2 N; f · g 2 I gi: 1 We describe a fast algorithm to compute the saturation, I :(x1 ··· xn) , of a homogeneous binomial ideal I. -

Quadratic Equations

Lecture 26 Quadratic Equations Quadraticpolynomials ................................ ....................... 2 Quadraticpolynomials ................................ ....................... 3 Quadraticequations and theirroots . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ........................ 4 How to solve a binomial quadratic equation. ......................... 5 Solutioninsimplestradicalform ........................ ........................ 6 Quadraticequationswithnoroots........................ ....................... 7 Solving binomial equations by factoring. ........................... 8 Don’tloseroots!..................................... ...................... 9 Summary............................................. .................. 10 i Quadratic polynomials A quadratic polynomial is a polynomial of degree two. It can be written in the standard form ax2 + bx + c , where x is a variable, a, b, c are constants (numbers) and a = 0 . 6 The constants a, b, c are called the coefficients of the polynomial. Example 1 (quadratic polynomials). 4 4 3x2 + x ( a = 3, b = 1, c = ) − − 5 − −5 x2 ( a = 1, b = c = 0 ) x2 1 5x + √2 ( a = , b = 5, c = √2 ) 7 − 7 − 4x(x + 1) x (this is a quadratic polynomial which is not written in the standard form. − 2 Its standard form is 4x + 3x , where a = 4, b = 3, c = 0 ) 2 / 10 Quadratic polynomials Example 2 (polynomials, but not quadratic) x3 2x + 1 (this is a polynomial of degree 3 , not 2 ) − 3x 2 (this is a polynomial of degree 1 , not 2 ) − Example 3 (not polynomials) 2 1 1 x + x 2 + 1 , x are not polynomials − x A quadratic polynomial ax2 + bx + c is called sometimes a quadratic trinomial. A trinomial consists of three terms. Quadratic polynomials of type ax2 + bx or ax2 + c are called quadratic binomials. A binomial consists of two terms. Quadratic polynomials of type ax2 are called quadratic monomials. A monomial consists of one term. Quadratic polynomials (together with polynomials of degree 1 and 0 ) are the simplest polynomials. -

The Evolution of Equation-Solving: Linear, Quadratic, and Cubic

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2006 The evolution of equation-solving: Linear, quadratic, and cubic Annabelle Louise Porter Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Porter, Annabelle Louise, "The evolution of equation-solving: Linear, quadratic, and cubic" (2006). Theses Digitization Project. 3069. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/3069 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EVOLUTION OF EQUATION-SOLVING LINEAR, QUADRATIC, AND CUBIC A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degre Master of Arts in Teaching: Mathematics by Annabelle Louise Porter June 2006 THE EVOLUTION OF EQUATION-SOLVING: LINEAR, QUADRATIC, AND CUBIC A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Annabelle Louise Porter June 2006 Approved by: Shawnee McMurran, Committee Chair Date Laura Wallace, Committee Member , (Committee Member Peter Williams, Chair Davida Fischman Department of Mathematics MAT Coordinator Department of Mathematics ABSTRACT Algebra and algebraic thinking have been cornerstones of problem solving in many different cultures over time. Since ancient times, algebra has been used and developed in cultures around the world, and has undergone quite a bit of transformation. This paper is intended as a professional developmental tool to help secondary algebra teachers understand the concepts underlying the algorithms we use, how these algorithms developed, and why they work.