Lachi Poverty Reduction Project Lprp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf | 90.92 Kb

PDMA PROVINCIAL DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY Provincial Emergency Operation Center Plot 46 A, Sector B2, Phase V, Hayatabad,Peshawar Phone: (091) 9219635, 9219636, Fax: (091) 9219637 www.pdma.gov.pk No. PDMA/PEOC/DSR/2021/JulE1925 Date: 19/07/2021 KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA DAILY SITUATION REPORT INFRA/ HUMAN INCIDENTS NATURE OF CAUSE OF CATTLE DISTRICT HUMAN LOSSES/ INJURIES INFRASTRUCTURE DAMAGES INCIDENT INCIDENT PERISHED DEATH INJURED HOUSES SCHOOLS OTHERS Mae Female Child Total Male Female Child Total Fully Partially Total Fully Partially Total Fully Partially Total Lower Dir Heavy Rain Other Damages 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 2 Upper Dir Heavy Rain Room Collapse 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 Kohat Heavy Rain Flash Flood 0 0 2 2 0 0 4 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Total(s) 0 0 2 2 0 0 4 4 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 2 2 INCIDENTS DETAIL DISTRICT DETAIL OF INCIDENT RESPONSE SOURCE On 19072021 in Mouza Chorlaki, Shakardara, 07 children swept away in Flash flood due to which the following casualties took place. Death 1. Ijaz S/o Shah Hussan 2. Ruqaya d/o Shah Hussan Injured Kohat Deputy Commissioner Office Kohat 1. Tauseef Alam s/o Sajid Hussain 2. Rabia Bibi d/o Shah Hussain 3. Fahad s/o Tahir Hussain 4. Rehan s/o Tahir Hussain Missing 1. Saad s/o Tahir Hussain 02 crops i.e. -

Annual Development Programme

ANNUAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 16 - PROGRAMME 2015 PROGRAMME DEVELOPMENT ANNUAL GOVERNMENT OF KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT JUNE, 2015 www.khyberpakhtunkhwa.gov.pk FINAL ANNUAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 2015-16 GOVERNMENT OF KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT http://www.khyberpakhtunkhwa.gov.pk Annual Development Programme 2015-16 Table of Contents S.No. Sector/Sub Sector Page No. 1 Abstract-I i 2 Abstract-II ii 3 Abstract-III iii 4 Abstract-IV iv-vi 5 Abstract-V vii 6 Abstract-VI viii 7 Abstract-VII ix 8 Abstract-VIII x-xii 9 Agriculture 1-21 10 Auqaf, Hajj 22-25 11 Board of Revenue 26-27 12 Building 28-34 13 Districts ADP 35-35 14 DWSS 36-50 15 E&SE 51-60 16 Energy & Power 61-67 17 Environment 68-69 18 Excise, Taxation & NC 70-71 19 Finance 72-74 20 Food 75-76 21 Forestry 77-86 22 Health 87-106 23 Higher Education 107-118 24 Home 119-128 25 Housing 129-130 26 Industries 131-141 27 Information 142-143 28 Labour 144-145 29 Law & Justice 146-151 30 Local Government 152-159 31 Mines & Minerals 160-162 32 Multi Sectoral Dev. 163-171 33 Population Welfare 172-173 34 Relief and Rehab. 174-177 35 Roads 178-232 36 Social Welfare 233-238 37 Special Initiatives 239-240 38 Sports, Tourism 241-252 39 ST&IT 253-258 40 Transport 259-260 41 Water 261-289 Abstract-I Annual Development Programme 2015-16 Programme-wise summary (Million Rs.) S.# Programme # of Projects Cost Allocation %age 1 ADP 1553 589965 142000 81.2 Counterpart* 54 19097 1953 1.4 Ongoing 873 398162 74361 52.4 New 623 142431 35412 24.9 Devolved ADP 3 30274 30274 21.3 2 Foreign Aid* * 148170 32884 18.8 Grand total 1553 738135 174884 100.0 Sector-wise Throwforward (Million Rs.) S.# Sector Local Cost Exp. -

RFP Document 11-12-2020.Pdf

Utility Stores Corporation (USC) Tender Document For Supply, Installation, Integration, Testing, Commissioning & Training of Next Generation Point of Sale System as Lot-1 And End-to-end Data Connectivity along with Platform Hosting Services as Lot-2 Of Utility Stores Locations Nationwide on Turnkey Basis Date of Issue: December 11, 2020 (Friday) Date of Submission: December 29, 2020 (Tuesday) Utility Stores Corporation of Pakistan (Pvt) Ltd, Head Office, Plot No. 2039, F-7/G-7 Jinnah Avenue, Blue Area, Islamabad Phone: 051-9245047 www.usc.org.pk Page 1 of 18 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 3 2. Invitation to Bid ................................................................................................................ 3 3. Instructions to Bidders ...................................................................................................... 4 4. Definitions ......................................................................................................................... 5 5. Interpretations.................................................................................................................... 7 6. Headings & Tiles ............................................................................................................... 7 7. Notice ................................................................................................................................ 7 8. Tender Scope .................................................................................................................... -

Download Download

Int. J. Econ. Environ. Geol. Vol. Khan11 (1 )et 0 al.1- 0/Int.J.Econ.Environ.Geol.Vol.9, 2020 11(1) 01-09, 2020 Open Access Journal home page: www.econ-environ-geol.org ISSN: 2223-957X c Reservoir Potential Evaluation of the Middle Paleocene Lockhart Limestone of the Kohat Basin, Pakistan: Petrophysical Analyses Nasar Khan1, Imran Ahmad1, Muhammad Ishaq2, Irfan U. Jan3, Wasim Khan1, Muhammad Awais2, Mohsin Salam1, Bilal Khan1 1Department of Geology, University of Malakand, Pakistan 2Department of Geology, University of Swabi, Pakistan 3National Centre of Excellence in Geology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan *Email: [email protected] Received: 25 September, 2019 Accepted: 12 February, 2020 Abstract: The Lockhart Limestone is evaluated for its reservoir potential by utilizing wireline logs of Shakardara-01 well from Kohat Basin, Pakistan. The analyses showed 28.03% average volume of shale (Vsh), 25.57% average neutron porosity (NPHI), 3.31% average effective porosity (PHIE), 76% average water saturation (Sw), and 24.10% average hydrocarbon saturation (Sh) of the Lockhart Limestone in Shakardara-01 well. Based on variation in petrophysical character, the reservoir units of the Lockhart Limestone are divided into three zones i.e., zone-1, zone-2 and zone-3. Out of these zones, zone-1 and zone-2 possess a poor reservoir potential for hydrocarbons as reflected by very low effective porosity (1.40 and 2.02% respectively) and hydrocarbon saturation (15 and 5.20%), while zone-3 has a moderate reservoir potential due to its moderate effective porosity (6.50%) and hydrocarbon saturation (52%) respectively. Overall, the average effective porosity of 3.31% and hydrocarbon saturation of 24.10% as well as 28.03% volume of shale indicated poor reservoir potential of the Lockhart Limestone. -

Contesting Candidates NA-1 Peshawar-I

Form-V: List of Contesting Candidates NA-1 Peshawar-I Serial No Name of contestng candidate in Address of contesting candidate Symbol Urdu Alphbeticl order Allotted 1 Sahibzada PO Ashrafia Colony, Mohala Afghan Cow Colony, Peshawar Akram Khan 2 H # 3/2, Mohala Raza Shah Shaheed Road, Lantern Bilour House, Peshawar Alhaj Ghulam Ahmad Bilour 3 Shangar PO Bara, Tehsil Bara, Khyber Agency, Kite Presented at Moh. Gul Abad, Bazid Khel, PO Bashir Ahmad Afridi Badh Ber, Distt Peshawar 4 Shaheen Muslim Town, Peshawar Suitcase Pir Abdur Rehman 5 Karim Pura, H # 282-B/20, St 2, Sheikhabad 2, Chiragh Peshawar (Lamp) Jan Alam Khan Paracha 6 H # 1960, Mohala Usman Street Warsak Road, Book Peshawar Haji Shah Nawaz 7 Fazal Haq Baba Yakatoot, PO Chowk Yadgar, H Ladder !"#$%&'() # 1413, Peshawar Hazrat Muhammad alias Babo Maavia 8 Outside Lahore Gate PO Karim Pura, Peshawar BUS *!+,.-/01!234 Khalid Tanveer Rohela Advocate 9 Inside Yakatoot, PO Chowk Yadgar, H # 1371, Key 5 67'8 Peshawar Syed Muhammad Sibtain Taj Agha 10 H # 070, Mohala Afghan Colony, Peshawar Scale 9 Shabir Ahmad Khan 11 Chamkani, Gulbahar Colony 2, Peshawar Umbrella :;< Tariq Saeed 12 Rehman Housing Society, Warsak Road, Fist 8= Kababiyan, Peshawar Amir Syed Monday, April 22, 2013 6:00:18 PM Contesting candidates Page 1 of 176 13 Outside Lahori Gate, Gulbahar Road, H # 245, Tap >?@A= Mohala Sheikh Abad 1, Peshawar Aamir Shehzad Hashmi 14 2 Zaman Park Zaman, Lahore Bat B Imran Khan 15 Shadman Colony # 3, Panal House, PO Warsad Tiger CDE' Road, Peshawar Muhammad Afzal Khan Panyala 16 House # 70/B, Street 2,Gulbahar#1,PO Arrow FGH!I' Gulbahar, Peshawar Muhammad Zulfiqar Afghani 17 Inside Asiya Gate, Moh. -

Pakistan National Nutrition Cluster Preparedness and Response Plan

National Nutrition Cluster 3 July 2013 Pakistan National Nutrition Cluster Preparedness and Response Plan The National Nutrition Cluster Preparedness and Response Plan is a common framework to guide the actions of all partners in the nutrition sector in the event of a disaster. It does not replace the need for planning by individual agencies in relation to their mandate and responsibilities within clusters, but provides focus and coherence to the various levels of planning that are required to respond effectively. It is envisioned that the Preparedness and Response Plan is a flexible and dynamic document that will be updated based on lessons learnt in future emergency responses. Each Provincial Nutrition Cluster will develop a Provincial Nutrition Cluster Preparedness and Response Plan, in cooperation with the Provincial Disaster Management Authority (PDMA) and the Department of Health (DoH). The Provincial Plans are stand-alone documents, however are linked and consistent with the National Plan. 1. Background The 2011 Pakistan National Nutrition Survey confirmed that Pakistan’s population still suffers from high rates of malnutrition and that the situation has not improved for several decades. Two out of every five (44 percent) of children under five are stunted, 32 percent are underweight and 15 percent suffer from acute malnutrition.1 Maternal malnutrition is also a significant problem; 15 percent of women of reproductive age have chronic energy deficiency. Women and children in Pakistan also suffer from some of the world’s highest levels of vitamin and mineral deficiencies. The malnutrition rates are very high by global standards and are much higher than Pakistan’s level of economic development should warrant. -

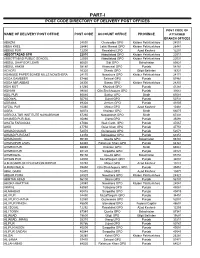

Part-I: Post Code Directory of Delivery Post Offices

PART-I POST CODE DIRECTORY OF DELIVERY POST OFFICES POST CODE OF NAME OF DELIVERY POST OFFICE POST CODE ACCOUNT OFFICE PROVINCE ATTACHED BRANCH OFFICES ABAZAI 24550 Charsadda GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24551 ABBA KHEL 28440 Lakki Marwat GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28441 ABBAS PUR 12200 Rawalakot GPO Azad Kashmir 12201 ABBOTTABAD GPO 22010 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22011 ABBOTTABAD PUBLIC SCHOOL 22030 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22031 ABDUL GHAFOOR LEHRI 80820 Sibi GPO Balochistan 80821 ABDUL HAKIM 58180 Khanewal GPO Punjab 58181 ACHORI 16320 Skardu GPO Gilgit Baltistan 16321 ADAMJEE PAPER BOARD MILLS NOWSHERA 24170 Nowshera GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24171 ADDA GAMBEER 57460 Sahiwal GPO Punjab 57461 ADDA MIR ABBAS 28300 Bannu GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28301 ADHI KOT 41260 Khushab GPO Punjab 41261 ADHIAN 39060 Qila Sheikhupura GPO Punjab 39061 ADIL PUR 65080 Sukkur GPO Sindh 65081 ADOWAL 50730 Gujrat GPO Punjab 50731 ADRANA 49304 Jhelum GPO Punjab 49305 AFZAL PUR 10360 Mirpur GPO Azad Kashmir 10361 AGRA 66074 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66075 AGRICULTUR INSTITUTE NAWABSHAH 67230 Nawabshah GPO Sindh 67231 AHAMED PUR SIAL 35090 Jhang GPO Punjab 35091 AHATA FAROOQIA 47066 Wah Cantt. GPO Punjab 47067 AHDI 47750 Gujar Khan GPO Punjab 47751 AHMAD NAGAR 52070 Gujranwala GPO Punjab 52071 AHMAD PUR EAST 63350 Bahawalpur GPO Punjab 63351 AHMADOON 96100 Quetta GPO Balochistan 96101 AHMADPUR LAMA 64380 Rahimyar Khan GPO Punjab 64381 AHMED PUR 66040 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66041 AHMED PUR 40120 Sargodha GPO Punjab 40121 AHMEDWAL 95150 Quetta GPO Balochistan 95151 -

DHIS Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Rapid Assessment 2013.Pdf

Rapid Assessment of District Health Information System 2013 2 Rapid Assessment of District Health Information System 2013 Table of Contents Acknowledgement ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Survey Team ................................................................................................................................................. 8 Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................ 9 1 Introduction and background .............................................................................................................. 10 1.1 Data and Management Information System (MIS) ..................................................................... 10 1.2 Background ................................................................................................................................. 10 1.3 Gaps of HMIS ............................................................................................................................. 11 1.4 District Health Information System (DHIS) ............................................................................... 11 1.5 Role of DHIS in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa ....................................................................................... 11 1.6 Comparison between HMIS and DHIS ...................................................................................... -

WHO Emergency Humanitarian Program Situation Report

WHO Emergency Humanitarian Program Situation Report Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and FATA Week 17 Date: April 22-28, 2012 1. Situation around IDP hosting districts A: Situation in “Jalozai” IDP camp, Nowshera district WHO shares updates on the disease situation on the newly influx of IDPs of Jalozai IDP camp with health cluster partners on district, provincial and national levels. WHO along with health cluster partners, UNICEF and provincial health authorities lead the emergency health response for the newly displaced IDPs in Jalozai camp and living in host communities in District Nowshera. Till 28th April, 2012, total IDPs population in KPK and FATA are 148,593families with 689007 individuals. Out of 148,593 families 41745 families are residing in host communities. 6215 families are residing in Jalozai IDP camp. In total Jalozai camp host 11,350 families with 53 970 individuals. This includes the new influx for Khyber and old caseload of Khyber and Bajaur Agencies. A total of 39 families with 173 individuals were registered on 28th April, 2012. Out of which 35 families with 156 individuals opted to live outside the camp and 4 families with 17 individuals elected to reside in Jalozai CAMP. Elsewhere in KP and FATA return has continued with more than 1000 families returning to South Waziristan. A total of 8 alerts including 6 measles and 2 AFP were reported and responded in this week. There were 6,704 consultations provided through health care provider, including acute respiratory infection (19% or 1,271 cases), acute diarrhoea (9.3% or 621 cases), skin infection (2% or 114) and suspected malaria (1% or 39 cases). -

KT15D00002-Repair Approach Street Dispensary Mirahmad Khel 220,000 220,000 220,000 220,000

District Project Description BE 2017-18 Final Budget Releases Expenditure KOHAT KT15D00002-Repair approach street dispensary MirAhmad khel 220,000 220,000 220,000 220,000 KOHAT KT15D00003-Const of Toilets, waiting shed andother 740,000 740,000 740,000 740,000 repair/maintenance of BHU Sherkot KOHAT KT15D00004-Pipe Line at BHU LandiKachai, Repair ofroof of RHC 649,000 649,000 649,000 649,000 UstarZai, Repair Work at RHC Usterzai. KOHAT KT15D00005-Maj; repair, w/s and elect, BHU KhaddarKhel 423,892 423,892 423,892 423,892 KOHAT KT15D00006-R&(M) works, const of waiting shed andG/Lat 04 No. 740,000 740,000 740,000 740,000 at RHC Lachi Bala KOHAT KT15D00007-R&(M) at BHU Ali Kach 740,000 740,000 740,000 740,000 KOHAT KT15D00008-Elect, W/S, Sanitary and building repairBHU Dolli 596,291 596,291 596,291 596,291 Banda KOHAT KT15D00009-Prov; of health related equipments andhygienic kits in 740,000 740,000 740,000 - civil hospital Shakardara Urban. Dev; works at civilHospital Shakardara. KOHAT KT15D00010-Solarization at BHU Gabari in U/CShakardara Rural-II. 740,000 740,000 740,000 - KOHAT KT15D00011-Major Repair of buildings and w/s of BHUGabari 740,000 740,000 740,000 740,000 KOHAT KT15D00012-Const;/repair works and S/F of Hand Pumpat BHU 488,122 488,122 488,122 488,122 Surgul KOHAT KT15D00013-Pavement of Dispensary street at U/CUrban III 507,090 507,090 507,090 507,000 KOHAT KT15D00014-Purchase of Hygienic kits,Purchase ofHematology 3,981,535 3,981,535 3,981,535 1,204,000 analyzer, for LMH Kohat, Purchase of Spray Pumps andInsecticides KOHAT KT15D00015-Const: -

IVAP Analysis Report April 2015

IVAP Analysis Report April 2015 IVAP is proudly funded by ECHO and DFID Background to KP/FATA Complex Emeregency The Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) is a semi-autonomous tribal region in northwestern Pakistan. It borders Afghanistan as well as Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Baluchistan provinces. More than 5 million people have been registered with the government and/or UNHCR as an internally displaced person (IDP) at some point since 2008 due to violent clashes in the country’s northwest region made up of FATA and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province. The 2014 military operations in North Waziristan and Khyber Agencies aggravated the situation, leading to the displacement of a further 233,000 families (approximately 1.4 million people). According to latest estimates from the UNHCR (2014), there are currently 1.6 million registered IDPs in KP/FATA. The vast majority of IDPs in KP/FATA chose to live in host communities (97%) rather than in camps for cultural reasons, including the privacy of females and difficult living conditions in the camps. The rest, who often have no other option, live in IDP camps (3%) (WFP). OCHA and other sources put the proportion of displaced families living outside of camps at 90% (OCHA, 18 June 2014; NYT, 20 June 2014; Al-Jazeera, 26 June 2014; IDMC, 12 June 2013, p.6). Displacement is difficult in Pakistan, which is ranked 146th on the list of 186 countries covered by the Human Development Index (UNDP, 24 July 2014, p.159). An estimated one fifth of its population are poor across the country, while in the KP/FATA a staggering one third of the population are poor (FDMA/UNDP, 2012, p.5; HDR, 2013, p.18; HPG, May 2013, p.21; UNDP, 27 October 2011). -

Checklist of Butterfly Fauna of Kohat, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

Arthropods, 2012, 1(3):112-117 Article Checklist of butterfly fauna of Kohat, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan Farzana Perveen, Ayaz Ahmad Department of Zoology, Hazara University, Garden Campus, Mansehra-21300, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Received 26 February 2012; Accepted 2 April 2012; Published online 5 September 2012 IAEES Abstract The butterflies play dual role, firstly as the pollinator, carries pollen from one flower to another and secondly their larvae act as the pest, injurious to various crops. Their 21 species were identified belonging to 3 different families from Kohat, Pakistan during September-December 2008. The reported families Namphalidae covered 33%, Papilionidae 10%, and Pieridae 57% biodiversity of butterflies of Kohat. In Namphalidae included: species belonging to subfamily Nymphalinae, Indian fritillary, Argynnis hyperbius Linnaeus; common castor, Ariadne merione (Cramer); painted lady, Cynthia cardui (Linnaeus); peacock pansy, Junonia almanac Linnaeus; blue pansy, J. orithya Linnaeus; common leopard, Phalantha phalantha (Drury); specie belonging to subfamily Satyrinae, white edged rock brown, Hipparchia parisatis (Kollar). In Papilionidae included: subfamily Papilioninae, lime butterfly, Papilio demoleus Linnaeus and common mormon, Pa. polytes Linnaeus. In Pieridae included: subfamily Coliaclinae, dark clouded yellow, Colias croceus (Geoffroy); subfamily Coliadinae, lemon emigrant, Catopsilia pomona Fabricius; little orange tip, C. etrida Boisduval; blue spot arab, Colotis protractus Butler; common grass yellow, Eumera hecab (Linnaeus); common brimstone, Gonepteryx rhamni (Linnaeus); yellow orange tip, Ixias pyrene Linnaeus; subfamily Pierinae, pioneer white butterfly, Belenoi aurota Bingham; Murree green-veined white, Pieris ajaka Moore; large cabbage white, P. brassicae Linnaeus; green-veined white, P. napi (Linnaeus); small cabbage white, P. rapae Linnaeus. The wingspan of collected butterflies, minimum was 25 mm of C.