Loneliness and Isolation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COVID-19 Bi-Weekly Bristol Statistics Update Tuesday 20 October 2020

COVID-19 bi-weekly Bristol statistics update Tuesday 20 October 2020 We aim to publish a COVID-19 bi-weekly Bristol statistics update twice a week, on Tuesday and Friday afternoons. This may be delayed until the following day, depending on when data is made available. These numbers and rates do change daily but were accurate when published on the date stated on the report. Summary Bristol's rate of 211.7 new cases per 100,000 population in the last 7 days (up to the 16th October) is considerably higher than for the previous 7 days (135.9 per 100,000). The reported rate represents 981 positive cases reported for Bristol over the past 7 days within a population of over 463,000 people. The trend is very clearly moving upwards both locally and nationally and the Bristol rate remains above England rate of 170.8 per 100,000 and is now ranked 46th among 149 English local authorities. Bristol is a Tier 1 area in the new national assessment system. This means we must continue to adhere to national instructions and guidelines. We are closely monitoring any changes and are considering the situation carefully. The regional R number remains at the same level as last week: a range of 1.3 – 1.6 reflecting the rise in cases locally and nationally. The range of R is above 1 indicating the epidemic is increasing. The majority of the increase in new cases are in younger age groups, and reflect schools returning and universities opening. However, we are also seeing a rise cases in working age adults . -

Table 1. School Admissions Reforms: Documentation Appendix Manipulable (More Or Allocation System Year from to Less?) Source References

Table 1. School Admissions Reforms: Documentation Appendix Manipulable (More or Allocation System Year From To Less?) Source References (1) Abdulkadiroglu, Atila and Tayfun Sonmez. 2003. "School Choice: A Mechanism Design Approach." American Economic Review , 101(1): 399‐410. (2) Abdulkadiroglu, Atila, Parag A. Pathak, Alvin Roth and Tayfun Sonmez. 2005. "The Boston Public Schools Match." American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings, 96: 368‐371. (3) Abdulkadiroglu, Atila, Parag A. Pathak, Alvin E. Roth, and Tayfun Sonmez. 2006. "Changing the Boston Mechanism: Strategy‐proofness as Equal Access." NBER Working Paper 11965. (4) Cook, Gareth. 2003. "School Assignment Flaws Detailed: Two economists study problem, offer relief." Boston Boston Public Schools (K, 6, 9) 2005 Boston GS Less A,B,E Globe, September 12. (5) BPS. 2002‐2010. "Introducing the Boston Public Schools." (1) Rossi, Rosalind. 2009. "8th Graders' Shot at Elite High Schools Better." Chicago Sun‐Times, November 12. (2) CPS, 2009. "Post Consent Decree Assignment Plan." Office of Academic Enhancement, November 11. (3) Chicago Public Schools. 2009. "New Admissions Process: Frequently Asked Questions." (describes the advice 4 4 Chicago Selective High Schools 2009 Boston SD Less A,B,C for re‐ranking schools). (1) CPS. 2010. "Guidelines for Magnet and Selective Enrollment Admissions for the 2011‐2012 School Year." November 29. (2) Joseph, Abigayil and Katie Ellis, 2010. "Refinements to 2011‐2012 Selective Enrollment and Magnet School Admission Policy." November 4. (3) CPS, 2011. "Application to Selective Enrollment High 4 6 2010 SD SD Less A,B,C Schools." Available at www.cpsoae.org, Last accessed December 28, 2011. (1) Ajayi, Kehinde. -

Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council: Social Determinants of Health Fund and Lobbying for National Change

Case study Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council: social determinants of health fund and lobbying for national change “Delivering improved public health outcomes “Local government expenditure is actually for residents is one of the councils top a mix of taxpayer cost and investment. The priorities. We have made a very good dedicated Public Health Grant is clearly an start this year at ensuring that it is not just investment as it both delivers improved citizen ‘another service’ – but that it is at the heart health outcomes and reduces avoidable of everything we do across policy, service costs to health and social care later on. delivery and decision making in the council. Non-health local government budget spend As we head into our second year we are areas – leisure services, education, children’s exploring what it means to be a public services, regeneration, housing – can all bring health council – not just a council with a ‘added public health value’ if undertaken in public health service. Many of the factors ways which address the Marmot Report’s that affect the health for our residents are areas of evidence-based health improvement determined by national policy – in areas action outside the healthcare system. One such as welfare reform, food policy, tobacco legitimate use of the Public Health Grant control and alcohol pricing. We therefore see is to find ways to lever governance and national advocacy for health promoting policy accountability for health outcomes from these (supporting the most vulnerable) as a growing non-health cost centres.” part of our local public health role”. Dominic Harrison, Councillor Mohammed Khan OBE, Director of Public Health Deputy Leader and Executive Member for Public Health and Adult Social Care New ways of working in Blackburn with Key messages Darwen’s public health operating model • Public health initiatives should be regarded include: as an investment in the social and economic wellbeing of the local area. -

Safer Sleeping Guidance for Children Blackburn with Darwen, Blackpool & Lancashire

SAFER SLEEPING GUIDANCE FOR CHILDREN BLACKBURN WITH DARWEN, BLACKPOOL & LANCASHIRE This documents supersedes previous version created January 2020 or earlier --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Document Updated: January 2020 Document ratified by CDOP: April 2020 Document to be reviewed: April 2021 (unless significant research/ updated national guidelines are released in the interim) Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.0 Aims ............................................................................................................................................................................ 2 2.0 Scope ........................................................................................................................................................................... 2 3.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 2 4.0 Definitions .................................................................................................................................................................. 2 5.0 Roles & Responsibilities ............................................................................................................................................. 4 5.1 Midwifery -

COVID-19 Update: 18Th June 2021

COVID-19 update: 18th June 2021 This update is split into the following sections: (1) Local COVID news (2) Local data on COVID cases (page 7) (3) National COVID news (page 9) (4) National data on COVID cases (page 13) (1) LOCAL COVID NEWS (A) A message from the Director of Public Health for our City Numbers of Covid cases in Brighton & Hove have been edging up for the past month or so. This week they leapt up by 160%. We knew there was a risk this might happen - now that the city’s opening up again and the Delta variant is among us. But I really didn’t want to have to report such a big increase in such a short time. Over half of those new cases were found in teenagers and young adults under the age of 25. This group hasn’t had the chance to get vaccinated yet, but that’s not the full story behind this jump. We know that a lot of transmission is occurring when people are socialising in close contact, often indoors, and then took the virus home with them. Fortunately, many of the cases were discovered by symptom-free LFD tests in time to do something about it. That just shows how effective routine, symptom-free testing is at finding and stopping the virus. Early detection means the people with Covid and their contacts have been able to self- isolate to slow down the virus. I want to thank everyone who has self-isolated and helped to keep Brighton & Hove safe. -

Blackburn with Darwen, Blackpool and Lancashire Local Flood Risk Management Strategy (Local Strategy)

Blackburn with Darwen, Blackpool and Lancashire Appendix 5(c) Local Flood Risk Management Strategy (Local Strategy) For more information about the Lancashire and Blackpool Flood Risk Management Strategy please contact:- Flood Risk Management Teams Lancashire County Council Cuerden Offices Highways Department Cuerden Way Preston PR5 6BS Blackpool Council Bickerstaffe Hose Blackpool FY1 1AD [email protected] Blackburn with Darwen, Blackpool and Lancashire Appendix 5(c) Local Flood Risk Management Strategy (Local Strategy) CONTENTS Executive Summary to be completed at the end Introduction Flood and Water Management Act Objectives & Measures Past & Future A Joint Local Strategy Other Sources of Flooding Our Vision for Local Flood Risk Management 1. Theme One - Roles and Responsibilities for Managing Flood Risk 2. Theme Two – Understanding Risk – Local Flood Risk within Lancashire 3. Theme Three – Sustainable Flood Risk Management Spatial Planning and Sustainable Drainage 4. Theme Four – Communication and Involvement 5. Theme Five – Funding 6. Theme 6 – Achieving a Nation of Climate Champions Summary Moving Forward – Implementing and Reviewing our Strategy Appendix 1 Glossary Business Plan Blackburn with Darwen, Blackpool and Lancashire Appendix 5(c) Local Flood Risk Management Strategy (Local Strategy) Lancashire Strategic Partnership Exec Summary to be completed and signed by Members of all 3 authorities Blackburn with Darwen, Blackpool and Lancashire Appendix 5(c) Local Flood Risk Management Strategy (Local Strategy) Figure 1 - Typical Flooding from local sources By courtesy of Cumbria County Council Blackburn with Darwen, Blackpool and Lancashire Appendix 5(c) Local Flood Risk Management Strategy (Local Strategy) Introduction Flood & Water Management Act The Flood and Water Management Act 2010 (FWMA) has put many of the recommendations made by the Pitt Review into legislation and as a result County Councils and Unitary Authorities have been designated as Lead Local Flood Authorities (LLFAs). -

Blackburn with Darwen Employment and Skills Strategy 2017 - 2040

Blackburn with Darwen Employment and Skills Strategy 2017 - 2040 Blackburn with Darwen Skills Strategy | 1 Introduction Blackburn with Darwen’s Employment and Skills Strategy aims to get more local people into work by delivering a skills system that meets the needs of both employers and residents of the borough. Why is it needed? We have too few people of working age in work – one of the lowest rates in the region. A significant number of employers raise skills, or the lack of, as a recruitment issue. They report concern about the impact this has on their continued productivity and growth of their business. This can be related to workforce development needs or an inability to recruit new talent, particularly from the local area. In addition to this, skills are not just important for regional, national and global competitiveness; they have the potential to transform life chances and to drive social mobility. We need to ensure that Blackburn with Darwen’s education system has the infrastructure and framework in place to capitalise on what the Government sees as the skill needs for the future as set out in the Industrial Strategy White Paper published in November 2017. The Lancashire Enterprise Partnership (LEP) already has a Skills and Employment Strategic Framework and will be producing its own ‘Industrial Strategy’ in response to the White Paper. The Borough needs to be well placed to shape and influence this to ensure it reflects the needs of Blackburn with Darwen. There are lots of organisations and sectors across the borough and wider Lancashire area who wish to address skills issues and improve outcomes. -

Lancashire, Blackpool, and Blackburn with Darwen: Local Restrictions - GOV.UK GOV.UK

04/10/2020 Lancashire, Blackpool, and Blackburn with Darwen: local restrictions - GOV.UK GOV.UK 1. Home (https://www.gov.uk/) 2. Coronavirus (COVID-19) (https://www.gov.uk/coronavirus-taxon) Guidance Lancashire, Blackpool, and Blackburn with Darwen: local restrictions Find out what you can and cannot do if you live, work or travel in affected local areas. Published 22 August 2020 Last updated 2 October 2020 — see all updates From: Department of Health and Social Care (https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-of-health- and-social-care) Contents Affected local areas Business and venue closures Social contact restrictions Travel restrictions Shielding Team sport and physical activity Weddings and funerals Religious ceremonies and places of worship Going to work Financial support – furlough and self-isolation Childcare Schools and colleges (face coverings) Universities and higher education Moving home An outbreak of coronavirus (COVID-19) has been identified in parts of Lancashire, Blackpool, and Blackburn with Darwen. The government and relevant local authorities are acting together to control the spread of the virus. Restrictions apply to the specified areas below. Affected local areas Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council area, with additional guidance and support applying in the following wards: Audley & Queen’s Park https://www.gov.uk/guidance/north-west-england-local-restrictions 1/13 04/10/2020 Lancashire, Blackpool, and Blackburn with Darwen: local restrictions - GOV.UK Bastwell & Daisyfield Billinge & Beardwood Blackburn -

Luton Borough Council Has an 'Audit Family' of Areas with Similar

Luton and its Audit Family Comparisons using data from the 2001 Census ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Research and Intelligence Team Department of Environment & Regeneration March 2003 Please note that Luton Borough Council is licensed by the Office for National Statistics to make available 2001 Census data to third parties. However this licence does not permit third parties to reproduce 2001 Census data without themselves obtaining a licence from the Office for National Statistics Luton Borough Council has an ‘Audit Family’ of areas with similar characteristics. Included in this Audit Family are: • Blackburn with Darwen • Leicester City • Rochdale • Bolton • Medway • Slough • Bradford • Milton Keynes • Telford and Wrekin • Coventry • Oldham • Thurrock • Derby City • Peterborough • Walsall Source: Audit Commission This paper makes comparisons across the Audit Family using the Key Statistics for Local Authorities from the 2001 Census. If you require further information on this report, please contact either Tanya Ridgeon ([email protected]) or Sharon Smith ([email protected]) ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Research and Intelligence Team Department of Environment & Regeneration March 2003 Please note that Luton Borough Council is licensed by the Office for National Statistics to make available 2001 Census data to third parties. However this licence does not permit third parties to reproduce -

United Kingdom

Functional urban areas http://www.oecd.org/cfe/regional-policy United Kingdom Note: This map is for illustrative purposes and is without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory covered by these maps. The OECD, in cooperation with the EU, has developed a harmonised definition of functional urban areas (FUAs). Being composed of a city (or core) and its commuting zone, FUAs encompass the economic and functional extent of cities based on daily people’s movements (OECD, 2012); (Dijkstra, Poelman, & Veneri, 2019). The definition of FUA aims at providing a functional/economic definition of cities and their area of influence, by maximising international comparability and overcoming the limitation of using purely administrative approaches. At the same time, the concept of FUA, unlike other approaches, ensures a minimum link to the government level of the city or metropolitan area. FUAs are listed below by size, according to four classes: • Small FUAs, with population between 50,000 and 100,000 • Medium-sized FUAs, with population between 100,000 and 250,000 • Metropolitan FUAs, with population between 250,000 and 1.5 million • Large metropolitan FUAs, with population above 1.5 million [email protected] Version: June 2021 Functional urban areas http://www.oecd.org/cfe/regional-policy A city is a group of local administrative units (i.e. LAU for European countries, such as municipality, local authorities, etc.) where at least 50% of its population live in an urban centre. An urban centre is defined as a cluster of contiguous grid cells of one square kilometer with a density of at least 1,500 inhabitants per square kilometer and a population of at least 50,000 inhabitants overall. -

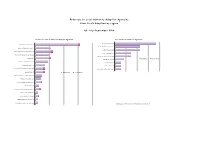

Q2 1617 LA Referrals

Referrals to Local Authority Adoption Agencies from First4Adoption by region Q2 July-September 2016 Yorkshire & The Humber LA Adoption Agencies North East LA Adoption Agencies Durham County Council 13 North Yorkshire County Council* 30 1 Northumberland County Council 8 Barnsley Adoption Fostering Unit 11 South Tyneside Council 8 Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council 11 2 North Tyneside Council 5 Bradford Metropolitan Borough Council 10 Redcar Cleveland Borough Council 5 Hull City Council 10 1 Web Referrals Phone Referrals Middlesbrough Council 3 East Riding Of Yorkshire Council 9 City Of Sunderland 2 Cumbria County Council 7 Gateshead Council 2 Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council 6 1 Newcastle Upon Tyne City Council 2 0 3.5 7 10.5 14 Leeds City Council 6 1 Web Referrals Phone Referrals Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council 5 Hartlepool Borough Council 4 North Lincolnshire Adoption Service 4 1 City Of York Council 3 North East Lincolnshire Adoption Service 3 1 Darlington Borough Council 2 Kirklees Metropolitan Council 2 1 Sheffield Metropolitan City Council 2 Wakefield Metropolitan District Council 2 * Denotes agencies with more than one office entry on the agency finder 0 10 20 30 40 North West LA Adoption Agencies Liverpool City Council 30 Cheshire West And Chester County Council 16 Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council 11 1 Manchester City Council 9 WWISH 9 Lancashire County Council 8 Oldham Council 8 1 Sefton Metropolitan Borough Council 8 2 Web Referrals Phone Referrals Wirral Adoption Team 8 Salford City Council 7 3 Bury Metropolitan -

Accountable Health: the Hidalgo Proposal and IHI Support of Learning

Accountable Health: The Hidalgo Proposal and IHI Support of Learning ItIntegrat tdCed Commun itBity Base dSd Serv ices to Improve Health Outcomes And Reduce Costs The 4 Componen ts o f a Health System PtiPrevention Diagnosis Treatment Management Current Payment Incentives Drive the System Prevention Payment Diagnosis Incentives Treatment MtManagement The Current Payment Paradigm $5,000 Procedures Payments are Based High End Testing On Relative Value Units, RVU’ s. Each interaction with a Patient has a Relative Value. $50 If you were Investing In Health Care, Where Would you invest? The Payment System Evaluation and Management Codes Supports High Cost Health Well Child Checks Care Investments, Not Clinical Preventive Services Prevention and Management Chronic Disease Management 99212 – 99215 Codes for Office Visit The Sppgiraling Cost C ycle +/-70% of Medical Care Almost 100% of Medical Care Payments are Public Investments are Private Public Private Payment ROI Investment Sources Strategies THE RVU / Payment Medicare and Medicaid System Encourages Pay for Physician Investments in Training Graduate Subspecialty Training Medical And High Cost Education Procedures and Tests One Approach to Changing ItidRdiCtIncentives and Reducing Cost If you want t o ch ange $4, 500 the Incentives for Health Care Investments how Procedures would you do it? High End Testing $75 Change the Slope of the RVU Evaluation and Management Codes / Payment System to Reduce Well Child Checks Return On Investment at the Clinical Preventive Services High End Chronic Disease