C:\WW Manuscripts\Back Issues\9-2 Mental Health\9-2 Koester.Wpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Galatians 6:6-18 8/31/14

1 Ted Kirnbauer Galatians 6:6-18 8/31/14 6:6 And let the one who is taught the word share all good things with him who teaches. 6:7 Do not be deceived, God is not mocked; for whatever a man sows, this he will also reap. 6:8 For the one who sows to his own flesh shall from the flesh reap corruption, but the one who sows to the Spirit shall from the Spirit reap eternal life. 6:9 And let us not lose heart in doing good, for in due time we shall reap if we do not grow weary. 6:10 So then, while we have opportunity, let us do good to all men, and especially to those who are of the household of the faith. 6:10 forms the conclusion to the paragraph and encapsulates the main idea behind verses 6-9; namely, we should do good to the household of the faith while we have opportunity to do so. Verse 6 gives an example of a good thing we can do. In verse 6 the word “share” most likely refers to giving financial support (Ro. 12:13; Phil. 4:15). Similarly, “good things” can also be used of the things necessary to live (Deut. 28:11; Lk. 12:18-19; 16:25). Thus, this is an exhortation to support those who teach the word of God (I Cor. 9:11, 14; I Tim. 5:17f.). Those who benefit from the instruction of a teacher should meet their teacher’s needs so that he can focus on studying and teaching the word of God without being distracted by worldly cares. -

Never Throw Freedom Away S C 8 8

NEVER THROW FREEDOM AWAY S C Sitting on top of the United States capitol so they toss in a few good works to be on the building is a 20-foot statue called the “Freedom safe side. They’re always getting down because 8 Lady”. She was sculpted by Italian artists in they’re never living up… as if it were up to 8 the city of Rome, and shipped across the Atlan- them in the first place! Rather than walk by tic Ocean to her perch in Washington, DC. faith they measure their righteousness by ad- A During the delivery, the ship carrying the hering to a set of religious standards. statue encountered a fierce storm. Howling They get bullied by the legalist – or en- winds and huge waves made the skipper fear slaved to an overworked conscience - or pay they might capsize, so he ordered the cargo homage to traditions that have outlasted their thrown overboard. But when the men went to purpose. In a million little ways their ap- toss over the Freedom Lady, the captain proach to life leans toward legalism, and in- shouted, “No, never! We’ll flounder before we sults the grace of God. throw “Freedom” away!” This is the message of But what people don’t realize is trying to be the book of Galatians… Never throw away your on the safe side can put you on the wrong freedom. Yet sadly, many Christians do… side… That’s the danger Paul addresses in the . They doubt if God’s grace is really sufficient, book of Galatians… Devotion Box - Cloning THE EVIL JUDAIZERS Christians ? Two things are amazing in this book– the The grace Paul preached came through revelation - grace of God and the stupidity of the Gala- not education or imagination. -

V. the Covenant of Christian Character 27

251876 Manual 2009_13 ins:244823 Manual 2005-09 1/11/10 4:06 PM Page 38 38 CHURCH CONSTITUTION 26.1. In one God—the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. 26.2. That the Old and New Testament Scriptures, given by plenary inspiration, contain all truth necessary to faith and Christian living. 26.3. That man is born with a fallen nature, and is, there- fore, inclined to evil, and that continually. 26.4. That the finally impenitent are hopelessly and eter- nally lost. 26.5. That the atonement through Jesus Christ is for the whole human race; and that whosoever repents and believes on the Lord Jesus Christ is justified and regenerated and saved from the dominion of sin. 26.6. That believers are to be sanctified wholly, subse- quent to regeneration, through faith in the Lord Jesus Christ. 26.7. That the Holy Spirit bears witness to the new birth, and also to the entire sanctification of believers. 26.8. That our Lord will return, the dead will be raised, and the final judgment will take place. V. The Covenant of Christian Character 27. To be identified with the visible Church is the blessed privilege and sacred duty of all who are saved from their sins and are seeking completeness in Christ Jesus. It is re- quired of all who desire to unite with the Church of the Naz- arene, and thus to walk in fellowship with us, that they shall show evidence of salvation from their sins by a godly walk and vital piety; and that they shall be, or earnestly de- sire to be, cleansed from all indwelling sin. -

Discernment in the Letter to the Galatians

Acta Theologica 2013 Suppl 17: 156-171 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/actat.v32i2S.10 ISSN 1015-8758 © UV/UFS <http://www.ufs.ac.za/ActaTheologica> D.F. Tolmie DISCERNMENT IN THE LETTER TO THE GALATIANS ABSTRACT Although discernment is not the primary focus of the Letter to the Galatians, a few references to this issue are found in the letter. These references are the focus of this study. After a brief overview of some approaches to discernment, three core elements of discernment are identified, namely reflection, choice and one’s relationship to God. Taking these elements as a point of departure, references to discernment in the following passages in the letter are investigated: 2:1-10; 2:11-21; 3:1-5 and 5:12-6:10. When one wishes to determine what the New Testament has to say on the subject of discernment, the Letter to the Galatians is perhaps not the logical place to begin. After all, is it not “red-hot rhetoric”? (Cosby 2002) Perhaps the section on the fruit of the Spirit and the works of the flesh in Galatians 5 would qualify for such an investigation? And then there is the singular occurrence of the verb dokimazevin in the letter, namely in Galatians 6:4. But is this all? Does the letter contain anything else that can contribute to our understanding of discernment? This is the issue that will receive attention in this study. First of all, a very basic question should be considered, namely that of what is meant by the concept of discernment. -

Grow Study 5: Growing in Generosity

STUDY 5 - GROWING IN GENEROSITY 2 CORINTHIANS 9:6-11 Jesus once said, “The poor you will always have with you.” (Mark 14:7) There will always be a need in our world to be generous in our giving to worthy causes. However, there is one cause that none will give to except for the Christian. This is the cause of the gospel and the care for the Christian family. “In this world, it is not what we take up but what we give up that makes us rich.” Henry Ward Beecher Read 2 Corinthians 9:6-11 1. In verses 6 and 7 what attitudes to giving are encouraged? 2. In verses 6 and 7 what attitudes to giving should we avoid? This chapter of the Bible speaks about a collection that Paul was organising for Jewish Christians in Jerusalem who were experiencing hardship and possibly famine. (Romans 15:26; 2 Corinthians 9:12) 3. In the following verses, how does Paul encourage these Christians to be generous? a. 2 Corinthians 9:6, 7 b. 2 Corinthians 9:8 c. 2 Corinthians 8:9 14 more to 4. Paul says that those who give will also gain. (“Whoever sows generously will also reap generously.” 2 Corinthians 9:6) In what respect will they gain? a. Verse 10? b. Verse 11? 5. According to verse 11, what is the end result of such Christian generosity? 6. Consider 1 Corinthians 16:1-2. What helpful instructions about Christian giving does it contain? What should we give to? The list of possibilities is endless and this itself can become an obstacle to giving. -

Galatians 3:6-20 Paul Has Made His Argument That Righteousness Is Imputed by God to Gentiles As Well As to Jewish People And

Galatians 3:6-20 Aaron Eime, Christ Church Jerusalem, 2021 Paul has made his argument that righteousness is imputed by God to Gentiles as well as to Jewish people and that it is not earned through the ‘works of the Law’ that create distinctions, boundaries and social standings between them. A new reality has been formed with the resurrection of the Messiah which Paul can see clearly now, yet others (his antagonists) are unable to at the present time. Jews and Gentiles are of equal value, infinitely loved by God who created all things and sustains all things, God has plans for all of humanity, and the Torah proves it! Paul had provided the example of the patriarch Abraham, which should satisfy both Gentile and Torah-observant Jewish listeners to Paul’s argument. Abraham both believed and trusted in God. He also kept the Torah even before it was delivered at Mt. Sinai, and God imputed to him righteousness. While the Book of Genesis does not contain the word “faith,” it says ‘Abraham believed God’. Paul does a midrash on the story to involve the faith of Abraham. ‘Faith’ or ‘faithfulness’ is an action word, the operating noun derived from a verb. Faith is not a one-time decision but the acting out of belief. Faith was never something attached to what you know, as even demons believe and they have seen God yet they have no faith. Twice in Genesis God declares that through Abraham all the nations of the world would be blessed. Thus the midrash is complete: Abraham walked out his belief in faithfulness, kept the Torah before it was given, received the covenant of circumcision as a sign forever, and God blessed him with righteousness. -

May 5, 2019 --- the Gospel of Faith Foretold --- Galatians 3:1-14

1 Sunday School Lesson Outline – Pleasant Zion Missionary Baptist Church – 3317 Toledano Street – New Orleans, La. May 5, 2019 --- The Gospel of Faith Foretold --- Galatians 3:1-14 Unit III – The True Gospel Introduction: ―It seems to happen with some frequency. The phone rings, and I answer. Immediately a recorded voice informs me that I have won a two-day, two-night trip to some exclusive getaway. Just as immediately I hang up the phone. Why? Because I know that the free trip comes with a cost. There are requirements. The idyllic vacation will be interrupted by seemingly endless, high-pressure sales presentations. Some people may consider this 'cost' an acceptable trade-off for the benefits received. But it is not my idea of a relaxing vacation. There is nothing necessarily wrong with offering free gifts in order to promote one’s product or business, but sometimes the free gift is not really free at all. In fact, many people assume this is the case, and even when offered something that is genuinely free, they immediately start wondering what the catch is. This is true in the case of the gospel.‖ – BE&I (See Gift of Grace on Page 7.) I. THE ARGUMENT FROM THE GALATIANS' EXPERIENCE -- Galatians 3:1-5 Galatians 3:1 1 O foolish Galatians, who hath bewitched you, that ye should not obey the truth, before whose eyes Jesus Christ hath been evidently set forth, crucified among you? A. Message of faith (Galatians 3:1). 1. ―Paul’s primary reason for writing to the Galatian Christians was to address the problem of legalism.‖ a. -

2020-2021 Bible Study #17 1/26/21

2020-2021 Bible Study #17 1/26/21 Epistles of Paul Epistle (s) Date/Journey Location of Comp Theme 1st and 2nd 50-51 /2nd Corinth 2nd coming of Thessalonians Jesus/end times Galatians 54/55/3rd Ephesus Judaizers heresy Review of our Last Class • Last week, we set the stage for Paul’s response to the crisis in the churches in Galatia • After four visits by Paul to those churches, the members of the four churches were taken in by the Judaizers demanding that they circumcise their sons and practice the law of Moses • The letter to the Galatians is Paul’s angry and frustrated response to this crisis • We saw how he proclaimed that even if an angel of God should present a different gospel from what he had taught them, they should not believe in it • We saw his defense of his authority as an Apostle of Christ, and how he had gone to Jerusalem (at the Council in 50 AD) and obtain a blessing from Peter, James, and others for his teaching Review of our Last Class (Cont) • We also saw the story of Paul chastising Peter in Antioch when he stepped back from the Gentiles after a few of the Judaizers showed up, implying that the Gentile converts were second-class Christians • Father also pointed out how Luther misunderstood this passage in his polemic on “Faith vs Works” • This entire letter highlights the difference in the early church between the Jewish converts and the Gentile converts Galatians 3 Galatians 3 • Galatians 3:1-2 “O foolish Galatians! Who has bewitched you, before whose eyes Jesus Christ was publicly portrayed as crucified? Let me ask -

Jerusalem, Our Mother: Metalepsis and Intertextuality in Galatians 4:21-31

Westminster Theological Journal 55 (1993) 299-320. Copyright © 1993 by Westminster Theological Seminary, cited with permission. JERUSALEM, OUR MOTHER: METALEPSIS AND INTERTEXTUALITY IN GALATIANS 4:21-31 KAREN H. JOBES Be glad, 0 barren woman, who bears no children; break forth and cry aloud, you who have no labor pains; because more are the children of the desolate woman than of her who has a husband. [Isa 54:1] IN Gal 4:21-31 the apostle Paul performs a hermeneutical tour de force unequaled in the NT. The Christians of Galatia were, unwittingly perhaps, in danger of rejecting the saving grace of Jesus Christ by embrac- ing the covenant of Jewish law expressed in circumcision. In these eleven short verses Paul effects a turnabout with enormous theological implication by arguing that if the Galatians really understood God's law, they would throw out any idea of being circumcised along with those persons who advocated it, because that is what the law itself demands! In a radical historical and theological reversal, Paul claims that Christians, and not Jews, are the promised sons of Abraham and are the true heirs of the promises of the Abrahamic covenant. The Hagar-Sarah trope1 of Gal 4:21-31 is the final argument of a section that begins in 3:1. Betz identifies this section as the probatio of Paul's dis- course, using a term from classical rhetoric.2 The probatio was that section of a first-century deliberative oration in which the heart of the matter was argued. Even if Galatians is not a formal oration, within this section Paul marshals his case against circumcision as proposed by the Judaizers. -

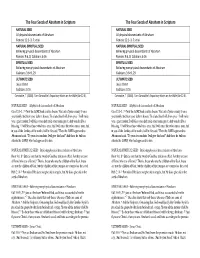

The Four Seeds of Abraham in Scripture the Four Seeds Of

The Four Seeds of Abraham in Scripture The Four Seeds of Abraham in Scripture NATURAL SEED NATURAL SEED All physical descendants of Abraham All physical descendants of Abraham Genesis 12:1–3, 7; et al. Genesis 12:1–3, 7; et al. NATURAL‐SPIRITUAL SEED NATURAL‐SPIRITUAL SEED Believing physical descendants of Abraham Believing physical descendants of Abraham Romans 9:6, 8; Galatians 6:16 Romans 9:6, 8; Galatians 6:16 SPIRITUAL SEED SPIRITUAL SEED Believing non‐physical descendants of Abraham Believing non‐physical descendants of Abraham Galatians 3:6–9, 29 Galatians 3:6–9, 29 ULTIMATE SEED ULTIMATE SEED Jesus Christ Jesus Christ Galatians 3:16 Galatians 3:16 Constable, T. (2003). Tom Constable’s Expository Notes on the Bible (Ge 22:9). Constable, T. (2003). Tom Constable’s Expository Notes on the Bible (Ge 22:9). NATURAL SEED – All physical descendants of Abraham NATURAL SEED – All physical descendants of Abraham Gen 12:1-3, 7 1 Now the LORD had said to Abram: "Get out of your country, From Gen 12:1-3, 7 1 Now the LORD had said to Abram: "Get out of your country, From your family And from your father's house, To a land that I will show you. 2 I will make your family And from your father's house, To a land that I will show you. 2 I will make you a great nation; I will bless you And make your name great; And you shall be a you a great nation; I will bless you And make your name great; And you shall be a blessing. -

Introduction to Paul's Letter to the Galatians

Reading The Greek New Testament www.misselbrook.org.uk/ Galatians Introduction to Paul's Letter to the Galatians Preface Paul's letters are not abstract theological treatises, they are letters written from the heart and addressed to churches for which Paul had an intimate concern. They formed a vital part of Paul's ministry, representing one element of the pastoral oversight of the apostle for churches founded through his ministry. They reflect much of the man and his passion for Christ while equally reflecting the situation and concerns of the congregations to which they were written. Of none is this more evident that the letter to the Galatians. In introducing what may be the first of Paul's letters1, we will trace the story of Paul, from his origins as the Pharisee, Saul of Tarsus, through conversion and commencement of missionary activity, down to the time when he dashed off this letter to the churches of Galatia. I do not apologise for this lengthy introduction; it is my conviction that the letter to the Galatians cannot rightly be understood apart from the experiences which Paul personally had suffered and the controversies which surrounded the birth of the first Gentile churches. In the words of Longenecker: "Whatever its place in the lists of antiquity, the letter to the Galatians takes programmatic primacy for (1) an understanding of Paul's teaching, (2) the establishing of a Pauline chronology, (3) the tracing out of the course of early apostolic history, and (4) the determination of many NT critical and canonical issues. It may even have been the first written of Paul's extant letters. -

Stewardship #4 the Rewards of Giving 2 Corinthians 9:6-15

Stewardship #4 The Rewards of Giving 2 Corinthians 9:6-15 We have come to the last of our messages from our series “Truths About Giving” and today’s study is titled “The Rewards of Giving.” In this series, we have looked at important aspects of giving but none is more important that today’s “Truths About Giving.” In our text, Paul draws to a close his teaching on the grace of giving with some tremendous insight on the rewarding ministry of Christian stewardship. In these verses he is determined to impress on his readers the all-important fact that the grace of giving is God's supreme method of rewarding those who give gifts as well as those who receive gifts. To bring this great truth to light, he speaks in these verses concerning four important matters. He speaks, first of all, concerning the fruitfulness in giving. Look at verse 6, "But this I say: He who sows sparingly will also reap sparingly, and he who sows bountifully will also reap bountifully.” Paul is teaching us that the laws of harvest operate not only in the natural, but also in the spiritual realm. Paul illustrates this fact by drawing attention to the farmer who sows his spring crop. The farmer knows that what he has sown in the spring he will harvest in the fall. One of those unalterable laws states that he will reap what he has sown. Moreover, the farmer understands that the proportion of his reaping will be determined by the proportion of his sowing. If he is foolish enough to sow sparingly he will reap sparingly; on the other hand, if he is wise enough to sow bountifully he will also reap bountifully.