Discernment in the Letter to the Galatians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Galatians 6:6-18 8/31/14

1 Ted Kirnbauer Galatians 6:6-18 8/31/14 6:6 And let the one who is taught the word share all good things with him who teaches. 6:7 Do not be deceived, God is not mocked; for whatever a man sows, this he will also reap. 6:8 For the one who sows to his own flesh shall from the flesh reap corruption, but the one who sows to the Spirit shall from the Spirit reap eternal life. 6:9 And let us not lose heart in doing good, for in due time we shall reap if we do not grow weary. 6:10 So then, while we have opportunity, let us do good to all men, and especially to those who are of the household of the faith. 6:10 forms the conclusion to the paragraph and encapsulates the main idea behind verses 6-9; namely, we should do good to the household of the faith while we have opportunity to do so. Verse 6 gives an example of a good thing we can do. In verse 6 the word “share” most likely refers to giving financial support (Ro. 12:13; Phil. 4:15). Similarly, “good things” can also be used of the things necessary to live (Deut. 28:11; Lk. 12:18-19; 16:25). Thus, this is an exhortation to support those who teach the word of God (I Cor. 9:11, 14; I Tim. 5:17f.). Those who benefit from the instruction of a teacher should meet their teacher’s needs so that he can focus on studying and teaching the word of God without being distracted by worldly cares. -

Never Throw Freedom Away S C 8 8

NEVER THROW FREEDOM AWAY S C Sitting on top of the United States capitol so they toss in a few good works to be on the building is a 20-foot statue called the “Freedom safe side. They’re always getting down because 8 Lady”. She was sculpted by Italian artists in they’re never living up… as if it were up to 8 the city of Rome, and shipped across the Atlan- them in the first place! Rather than walk by tic Ocean to her perch in Washington, DC. faith they measure their righteousness by ad- A During the delivery, the ship carrying the hering to a set of religious standards. statue encountered a fierce storm. Howling They get bullied by the legalist – or en- winds and huge waves made the skipper fear slaved to an overworked conscience - or pay they might capsize, so he ordered the cargo homage to traditions that have outlasted their thrown overboard. But when the men went to purpose. In a million little ways their ap- toss over the Freedom Lady, the captain proach to life leans toward legalism, and in- shouted, “No, never! We’ll flounder before we sults the grace of God. throw “Freedom” away!” This is the message of But what people don’t realize is trying to be the book of Galatians… Never throw away your on the safe side can put you on the wrong freedom. Yet sadly, many Christians do… side… That’s the danger Paul addresses in the . They doubt if God’s grace is really sufficient, book of Galatians… Devotion Box - Cloning THE EVIL JUDAIZERS Christians ? Two things are amazing in this book– the The grace Paul preached came through revelation - grace of God and the stupidity of the Gala- not education or imagination. -

V. the Covenant of Christian Character 27

251876 Manual 2009_13 ins:244823 Manual 2005-09 1/11/10 4:06 PM Page 38 38 CHURCH CONSTITUTION 26.1. In one God—the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. 26.2. That the Old and New Testament Scriptures, given by plenary inspiration, contain all truth necessary to faith and Christian living. 26.3. That man is born with a fallen nature, and is, there- fore, inclined to evil, and that continually. 26.4. That the finally impenitent are hopelessly and eter- nally lost. 26.5. That the atonement through Jesus Christ is for the whole human race; and that whosoever repents and believes on the Lord Jesus Christ is justified and regenerated and saved from the dominion of sin. 26.6. That believers are to be sanctified wholly, subse- quent to regeneration, through faith in the Lord Jesus Christ. 26.7. That the Holy Spirit bears witness to the new birth, and also to the entire sanctification of believers. 26.8. That our Lord will return, the dead will be raised, and the final judgment will take place. V. The Covenant of Christian Character 27. To be identified with the visible Church is the blessed privilege and sacred duty of all who are saved from their sins and are seeking completeness in Christ Jesus. It is re- quired of all who desire to unite with the Church of the Naz- arene, and thus to walk in fellowship with us, that they shall show evidence of salvation from their sins by a godly walk and vital piety; and that they shall be, or earnestly de- sire to be, cleansed from all indwelling sin. -

Grow Study 5: Growing in Generosity

STUDY 5 - GROWING IN GENEROSITY 2 CORINTHIANS 9:6-11 Jesus once said, “The poor you will always have with you.” (Mark 14:7) There will always be a need in our world to be generous in our giving to worthy causes. However, there is one cause that none will give to except for the Christian. This is the cause of the gospel and the care for the Christian family. “In this world, it is not what we take up but what we give up that makes us rich.” Henry Ward Beecher Read 2 Corinthians 9:6-11 1. In verses 6 and 7 what attitudes to giving are encouraged? 2. In verses 6 and 7 what attitudes to giving should we avoid? This chapter of the Bible speaks about a collection that Paul was organising for Jewish Christians in Jerusalem who were experiencing hardship and possibly famine. (Romans 15:26; 2 Corinthians 9:12) 3. In the following verses, how does Paul encourage these Christians to be generous? a. 2 Corinthians 9:6, 7 b. 2 Corinthians 9:8 c. 2 Corinthians 8:9 14 more to 4. Paul says that those who give will also gain. (“Whoever sows generously will also reap generously.” 2 Corinthians 9:6) In what respect will they gain? a. Verse 10? b. Verse 11? 5. According to verse 11, what is the end result of such Christian generosity? 6. Consider 1 Corinthians 16:1-2. What helpful instructions about Christian giving does it contain? What should we give to? The list of possibilities is endless and this itself can become an obstacle to giving. -

2020-2021 Bible Study #17 1/26/21

2020-2021 Bible Study #17 1/26/21 Epistles of Paul Epistle (s) Date/Journey Location of Comp Theme 1st and 2nd 50-51 /2nd Corinth 2nd coming of Thessalonians Jesus/end times Galatians 54/55/3rd Ephesus Judaizers heresy Review of our Last Class • Last week, we set the stage for Paul’s response to the crisis in the churches in Galatia • After four visits by Paul to those churches, the members of the four churches were taken in by the Judaizers demanding that they circumcise their sons and practice the law of Moses • The letter to the Galatians is Paul’s angry and frustrated response to this crisis • We saw how he proclaimed that even if an angel of God should present a different gospel from what he had taught them, they should not believe in it • We saw his defense of his authority as an Apostle of Christ, and how he had gone to Jerusalem (at the Council in 50 AD) and obtain a blessing from Peter, James, and others for his teaching Review of our Last Class (Cont) • We also saw the story of Paul chastising Peter in Antioch when he stepped back from the Gentiles after a few of the Judaizers showed up, implying that the Gentile converts were second-class Christians • Father also pointed out how Luther misunderstood this passage in his polemic on “Faith vs Works” • This entire letter highlights the difference in the early church between the Jewish converts and the Gentile converts Galatians 3 Galatians 3 • Galatians 3:1-2 “O foolish Galatians! Who has bewitched you, before whose eyes Jesus Christ was publicly portrayed as crucified? Let me ask -

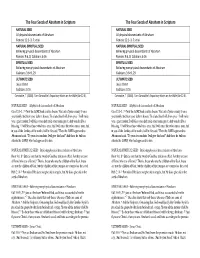

The Four Seeds of Abraham in Scripture the Four Seeds Of

The Four Seeds of Abraham in Scripture The Four Seeds of Abraham in Scripture NATURAL SEED NATURAL SEED All physical descendants of Abraham All physical descendants of Abraham Genesis 12:1–3, 7; et al. Genesis 12:1–3, 7; et al. NATURAL‐SPIRITUAL SEED NATURAL‐SPIRITUAL SEED Believing physical descendants of Abraham Believing physical descendants of Abraham Romans 9:6, 8; Galatians 6:16 Romans 9:6, 8; Galatians 6:16 SPIRITUAL SEED SPIRITUAL SEED Believing non‐physical descendants of Abraham Believing non‐physical descendants of Abraham Galatians 3:6–9, 29 Galatians 3:6–9, 29 ULTIMATE SEED ULTIMATE SEED Jesus Christ Jesus Christ Galatians 3:16 Galatians 3:16 Constable, T. (2003). Tom Constable’s Expository Notes on the Bible (Ge 22:9). Constable, T. (2003). Tom Constable’s Expository Notes on the Bible (Ge 22:9). NATURAL SEED – All physical descendants of Abraham NATURAL SEED – All physical descendants of Abraham Gen 12:1-3, 7 1 Now the LORD had said to Abram: "Get out of your country, From Gen 12:1-3, 7 1 Now the LORD had said to Abram: "Get out of your country, From your family And from your father's house, To a land that I will show you. 2 I will make your family And from your father's house, To a land that I will show you. 2 I will make you a great nation; I will bless you And make your name great; And you shall be a you a great nation; I will bless you And make your name great; And you shall be a blessing. -

Introduction to Paul's Letter to the Galatians

Reading The Greek New Testament www.misselbrook.org.uk/ Galatians Introduction to Paul's Letter to the Galatians Preface Paul's letters are not abstract theological treatises, they are letters written from the heart and addressed to churches for which Paul had an intimate concern. They formed a vital part of Paul's ministry, representing one element of the pastoral oversight of the apostle for churches founded through his ministry. They reflect much of the man and his passion for Christ while equally reflecting the situation and concerns of the congregations to which they were written. Of none is this more evident that the letter to the Galatians. In introducing what may be the first of Paul's letters1, we will trace the story of Paul, from his origins as the Pharisee, Saul of Tarsus, through conversion and commencement of missionary activity, down to the time when he dashed off this letter to the churches of Galatia. I do not apologise for this lengthy introduction; it is my conviction that the letter to the Galatians cannot rightly be understood apart from the experiences which Paul personally had suffered and the controversies which surrounded the birth of the first Gentile churches. In the words of Longenecker: "Whatever its place in the lists of antiquity, the letter to the Galatians takes programmatic primacy for (1) an understanding of Paul's teaching, (2) the establishing of a Pauline chronology, (3) the tracing out of the course of early apostolic history, and (4) the determination of many NT critical and canonical issues. It may even have been the first written of Paul's extant letters. -

Stewardship #4 the Rewards of Giving 2 Corinthians 9:6-15

Stewardship #4 The Rewards of Giving 2 Corinthians 9:6-15 We have come to the last of our messages from our series “Truths About Giving” and today’s study is titled “The Rewards of Giving.” In this series, we have looked at important aspects of giving but none is more important that today’s “Truths About Giving.” In our text, Paul draws to a close his teaching on the grace of giving with some tremendous insight on the rewarding ministry of Christian stewardship. In these verses he is determined to impress on his readers the all-important fact that the grace of giving is God's supreme method of rewarding those who give gifts as well as those who receive gifts. To bring this great truth to light, he speaks in these verses concerning four important matters. He speaks, first of all, concerning the fruitfulness in giving. Look at verse 6, "But this I say: He who sows sparingly will also reap sparingly, and he who sows bountifully will also reap bountifully.” Paul is teaching us that the laws of harvest operate not only in the natural, but also in the spiritual realm. Paul illustrates this fact by drawing attention to the farmer who sows his spring crop. The farmer knows that what he has sown in the spring he will harvest in the fall. One of those unalterable laws states that he will reap what he has sown. Moreover, the farmer understands that the proportion of his reaping will be determined by the proportion of his sowing. If he is foolish enough to sow sparingly he will reap sparingly; on the other hand, if he is wise enough to sow bountifully he will also reap bountifully. -

Galatians 6:1-18 ~ Discussion Questions

Galatians 6:1-18 ~ Discussion Questions 1. How easily do you share your time and skills with others? How do you feel when you offer to serve but are turned down? How do you feel when you aren’t thanked for going out of your way to serve somebody? 2. What is the best approach to helping a Christian brother caught in sin? Paul says “you who are spiritual” should help. To whom does this refer? (6:1, 4:6) 3. What are three dangers of correcting someone else’s sin or wrong? (6:1) 4. Do you want the approval of others? Is it bad to take pride in yourself? (6:4-5, 5:20, Philippians 2:3) 5. Why is it important to have Christian friends? Wouldn’t it be easier to live as a hermit or monk? 6. What do you think Paul is saying in Verse 6:6? (1 Corinthians 9:7-14, 1 Timothy 5:17-18) 7. Do you believe that you reap what you sow? (6:7-9, Job 4:8) 8. What does the word “therefore” (or “so then”) indicate in Verse 6:10? 9. In Verse 6:11, Paul says, “see what large letters I use...” What is the meaning of this? 10. Why were the Judaizers trying to compel the Christians to be circumcised? (6:12) 11. In your own words, what’s the meaning of v. 6:14 – May I never boast except in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, through which the world has been crucified to me, and I to the world. -

The Antioch Church Helped

PRESCHOOL UNIT 1. SESSION 4 The Antioch Worship Church Helped BASED ON ACTS 11:19-30 THE BIBLE MEETS LIFE WEEKLY VERSE: Help one another in Parents, today your child love. Galatians 5:13 heard that people at church give and help others. The LIFE POINT: People at church give and Antioch church gave gifts to help others. help the Jerusalem church during a time of famine. The people in the Jerusalem church heard about a new church in Antioch. They sent Barnabas to visit the LIVE IT OUT Antioch church. Barnabas encouraged the people in the new church to serve God, teach about Jesus, and learn about Him. Many people in Review the Bible story with your child. Remind him that Antioch began to believe that Jesus was God’s Son. people at church help others. Barnabas brought Saul to Antioch to help teach the people. They Plan a ministry project with stayed in Antioch for a year. More people in Antioch began to believe in your family. Include your Jesus. The people who believed in Jesus were called Christians. children in the planning and One day some men from Jerusalem came to the Antioch church. execution of the project. One of the men, a prophet named Agabus, told the church that soon Thank God for the opportunity the people in Judea would not have enough food to eat. Many people to help others. would be hungry. The people in the Antioch church decided to help. Everyone in the Antioch church gave as much food and money as they could. -

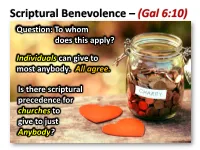

Scriptural Benevolence – (Gal 6:10) Question: to Whom Does This Apply?

Scriptural Benevolence – (Gal 6:10) Question: To whom does this apply? Individuals can give to most anybody. All agree. Is there scriptural precedence for churches to give to just Anybody? Biblical Pattern: Churches to Saints in Need (Acts 2:42) All who believed were together & had all things common… sharing w/all (Acts 4:34-35) Not a needy person among Jerusalem them.. Owners would sell them & lay Saints proceeds at apostles’ feet... dist to each (Acts 11:29-30) Send Relief of brethren in Judea.. Sending it to the elders by Barnabas… Antioch Judean Saints (1 Cor 16:1-2) Concerning the collection for the saints v.3 (2 Cor8:4) Support of saints Corinth Jerusalem Saints (Rom 15:26) Poor among saints Is Galatians 6 Church or Individual Action? True, Gal 1:2 Is Addressed to Churches of Galatia Now is Galatians 6 Church Action? Gal 6:1a “Even if a man is caught in any trespass, you [Individuals] who are spiritual, restore such a one in a spirit of meekness” Gal 6:1b Each one looking to yourself, [Indiv not church] lest you too be tempted. Is Galatians 6 Church or Individual Action? Gal 6:2 Bear one another's [Individual’s] burdens, and thus fulfill the law of Christ. Gal 6:3 For if anyone thinks he is something when he is nothing, he deceives himself. (singular pronouns) John 13:34 Love one another Jas 2:8 Royal Law Love neighbor Is Galatians 6 Church or Individual Action? Gal 6:4 But let each one examine his own work, and then he will have reason for boasting in regard to him self alone, and not in regard to another. -

'Don't Be a Hypocrite

1 ‘Don’t be a hypocrite.’ (5) A little boy was waiting for his mother to come out of the supermarket. As he waited, he was approached by a man who asked, ‘Son, can you tell me where the post office is?’ The little boy replied, ‘Sure, just go straight down the street, when you get to the roundabout, turn to your right.’ The man thanked the boy kindly and said, ‘I’m the new preacher in town, and I’d like for you to come to church on Sunday. I’ll show you how to get to Heaven.’ The little boy replied with a chuckle, ‘Aw, come on preacher, you don’t even know the way to the post office!’ In today’s world, there are many religious groups who claim they know the way to heaven and during days of the New Testament it was much the same. Some people were saying, ‘you can get to heaven by following Jesus and being obedient to the Gospel’. Others were saying, ‘well, it’s true, you need to follow Jesus but you also need to be circumcised and follow the traditions of Judaism’. We’re continuing our sermon series on Paul’s letter to the Galatians today and we’re going read about Paul rebuking Peter because of his hypocrisy. But before we get into the actually text, let me share with you the background to the text first. Now even though we don’t know all the details, Paul presents us with the seriousness of legalism in the church by recording a division that took place as the result of the work and teaching of legalistic teachers.