North Shields Forty Years On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Martin Road Project

THE 02-52 MARTIN ROAD PROJECT Crime and Disorder Reduction Northumbria Police ACC Paul Leighton Contact: Sergeant Steve Todd Wallsend Area Command 20 Alexandra Street Wallsend Telephone: 0181214 6555 ext 63311 Fax: 01661 863354 Email: [email protected] Martin Road Project - Executive Summary THE Martin Road area of Howdon, North Tyneside, is like many others in urban Britain. A mainly local authority-run estate, its high levels of unemployment and deprivation had led to an acceptance by residents and local agencies that anti-social behaviour and juvenile disorder were inevitable. But in this particular area, the problems gradually worsened until they reached a stage where effective, permanent, sustainable action was the only option. In the six months from January 1 2001, incidents of serious disorder were becoming excessive. They peaked between March and May 2001 when police officers and fire-fighters were regularly attacked by large groups of missile-throwing youths, council houses were set on fire and nearby Metro trains and other property damaged. The residents shared the views of the emergency services that enough was enough and brought their problems to the March meeting of the local Police and Community Forum. A month later the first meeting of the Martin Road Public Safety Group was held and the first step had been taken on the road to recovery. People representing the police, the local authority, a housing association, the fire service, local businesses, the main transport operator, residents and schools met to tackle the problem - and find a solution - together. Shared information and a residents survey confirmed high levels of serious disorder including arson, damage and missile throwing. -

Northumberland. Humshaugh

DIREOTORY.] NORTHUMBERLAND. HUMSHAUGH. 143 Middlemiss George & John, farmers, lery Volunteers (No. 4 Battery), Maj. Stephenson Bartholomew, Fishing Boat Boulmer farm W. Robinson inn, Boulmer Middlemiss William & Alexander, far- Patterson Thomas, farmer, Snableazes Stephenson Robt. shopkeeper, Boulmer mers, Seaton house Richardson Henry,shopkeeper,Boulmer Wood Penniment, grocer, Houlmer Moore George, boot maker Robin80n George, blacksmith Murray Gilbert, cartwright Scott James Laidler, farmer, Pepper- Little Houghton. Northumberland Whinstone Co. quarry moor farm Brown Major Robert owners (Mark Robison, manager; Sheel George, shopkeeper, &; post office McLain Mrs offices, 28 Clayton st. we. Newcastle) Sheel Mary (Mrs.), shopkeeper Glaholme William, farmer Northumberland 2nd (The Percy) Artil- Smith J ohn,farmer,LongHoughton hall Richardsou John, lime burner HOWDON-ON-TYNE, 2 miles east from Wallsend lation of the parish in I891 was 6,783, local board district, and 6 north-east from Newcastle-upon-Tyne, is a parish 962. formed from Wallsend Sept. 30, r859, and comprises Sexton, Robert Turnbull. W1LLINGTON township, south of the North Eastern railway, POST & M. O. 0., S. B. & Annuity & Insurance Office, and HOWDEN PANS township, in the Wansbeck division of Howdon-on-Tyne. _ George Teasdale, sub-postmaster. the county, eastern division of Castle ward, Tynemouth Letters arrive fromWillington Quay R.S.O. at 8 a.m.& 3 & petty sessional division and union, North Shields county & d' h d h 0a d·· I d f T h hd 7p·m.. lspatc e t ereto at 9·3 ,m., 12·30,3·30,5·30 court lstnct, rura eanery 0 ynemout, arc eaconry & 9.30 p.m.; snndays 3.45 p.m. -

Royal Quays Marina North Shields Q2019

ROYAL QUAYS MARINA NORTH SHIELDS Q2019 www.quaymarinas.com Contents QUAY Welcome to Royal Quays Marina ................................................. 1 Marina Staff .................................................................................... 2 plus Marina Information .....................................................................3-4 RYA Active Marina Programme .................................................... 4 Lock Procedure .............................................................................. 7 offering real ‘added value’ Safety ............................................................................................ 11 for our customers! Cruising from Royal Quays ....................................................12-13 Travel & Services ......................................................................... 13 “The range of services we offer Common Terns at Royal Quays .................................................. 14 A Better Environment ................................................................. 15 and the manner in which we Environmental Support ............................................................... 15 deliver them is your guarantee Heaviest Fish Competition ......................................................... 15 of our continuing commitment to Boat Angling from Royal Quays ................................................. 16 provide our berth holders with the Royal Quays Marina Plan .......................................................18-19 Eating & Drinking Guide ............................................................ -

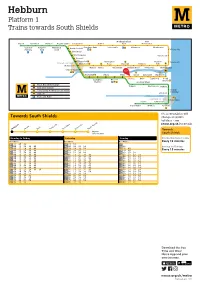

Hebburn Platform 1 Trains Towards South Shields

Hebburn Platform 1 Trains towards South Shields Northumberland West Airport Bank Foot Fawdon Regent Centre Longbenton Benton Park Monkseaton Four Lane Ends Palmersville Shiremoor Monkseaton Callerton Kingston Wansbeck South Gosforth Parkway Park Road Whitley Bay Ilford Road West Jesmond Cullercoats Jesmond Haymarket Chillingham Meadow Tynemouth Newcastle City Centre Monument Road Wallsend Howdon Well St James Manors Byker Walkergate Hadrian Road Percy Main North Shields Central Station River Tyne Gateshead Felling Pelaw Jarrow Simonside Chichester Hebburn Bede Tyne Dock South Heworth Gateshead Shields Stadium Brockley Whins Main Bus Interchange Fellgate East Boldon Seaburn Rail Interchange Ferry (only A+B+C tickets valid) Stadium of Light Airport St Peter’s River Wear Park and Ride Sunderland City Centre Sunderland Pallion University South Hylton Park Lane These timetables will Towards South Shields change on public holidays - see nexus.org.uk for details. Hebburn Jarrow Bede Simonside Tyne Dock Chichester South Shields Towards Approx. journey times South Shields Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Daytime Monday to Saturday Hour Minutes Hour Minutes Hour Minutes Every 12 minutes 05 24 37 48 05 31 54 05 06 00 12 24 36 48 06 09 24 39 54 06 46 Evenings and Sundays 07 00 12 24 36 48 07 09 24 39 54 07 15 40 08 00 12 24 36 48 08 09 24 39 54 08 10 40 Every 15 minutes 09 00 12 24 36 48 09 09 23 38 49 09 09 39 54 10 00 12 24 36 48 10 01 13 25 37 49 10 09 24 39 54 11 00 12 24 36 48 11 01 13 25 37 49 11 09 24 39 54 12 00 12 24 36 48 12 01 13 25 37 -

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society Unwanted

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society baptism birth marriage No Gsurname Gforename Bsurname Bforename dayMonth year place death No Bsurname Bforename Gsurname Gforename dayMonth year place all No surname forename dayMonth year place Marriage 933ABBOT Mary ROBINSON James 18Oct1851 Windermere Westmorland Marriage 588ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul1869 Tynemouth Marriage 935ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 Jul1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland Marriage1561ABBS Maria FORDER James 21May1861 Brooke, Norfolk Marriage 1442 ABELL Thirza GUTTERIDGE Amos 3 Aug 1874 Eston Yorks Death 229 ADAM Ellen 9 Feb 1967 Newcastle upon Tyne Death 406 ADAMS Matilda 11 Oct 1931 Lanchester Co Durham Marriage 2326ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth SOMERSET Ernest Edward 26 Dec 1901 Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne Marriage1768ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16Oct1849 Coughton Northampton Death 1556 ADAMS Thomas 15 Jan 1908 Brackley, Norhants,Oxford Bucks Birth 3605 ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth 18 May 1876 Stockton Co Durham Marriage 568 ADAMSON Annabell HADAWAY Thomas William 30 Sep 1885 Tynemouth Death 1999 ADAMSON Bryan 13 Aug 1972 Newcastle upon Tyne Birth 835 ADAMSON Constance 18 Oct 1850 Tynemouth Birth 3289ADAMSON Emma Jane 19Jun 1867Hamsterley Co Durham Marriage 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth Marriage1292ADAMSON Jane HARTBURN John 2Sep1839 Stockton & Sedgefield Co Durham Birth 3654 ADAMSON Julie Kristina 16 Dec 1971 Tynemouth, Northumberland Marriage 2357ADAMSON June PORTER William Sidney 1May 1980 North Tyneside East Death 747 ADAMSON -

North Shields-North Tyneside Hospital-Cobalt-Howden-Wallsend- Benton

North Shields-North Tyneside Hospital-Cobalt-Howden-Wallsend- 42 Benton Asda-Killingworth-Cramlington Monday to Friday (except Public Holidays) Service Number 42 42 42A 42 42A 42 42A 42 42A 42 42A 42 42A 42 42A 42 42A 42 42A 42 North Shields Bedford Street <m> ---- ---- ---- ---- 0656 0717 0744 0815 0904 0939 1011 1041 1111 1141 1211 1241 1311 1341 1411 1442 Hawkeys Lane Health Centre ---- ---- ---- ---- 0702 0724 0751 0822 0911 0946 1018 1048 1118 1148 1218 1248 1318 1348 1418 1449 Morwick Road/Netherton Avenue ---- ---- ---- ---- 0706 0729 0756 0829 0915 0950 1022 1052 1122 1152 1222 1252 1322 1352 1422 1453 North Tyneside Hospital ---- ---- ---- ---- 0711 0734 0801 0835 0921 0956 1028 1058 1128 1158 1228 1258 1328 1358 1428 1500 New York Westminster Avenue ---- ---- ---- ---- 0714 0737 0804 0838 0924 0959 1031 1101 1131 1201 1231 1301 1331 1401 1431 1503 Cobalt Park Procter & Gamble ---- ---- ---- ---- 0721 0745 0814 0848 0931 1006 1038 1108 1138 1208 1238 1308 1338 1408 1438 1510 Coniston Road/Matfen Gardens ---- B ---- B 0727 0753 0823 0856 0938 1013 1045 1115 1145 1215 1245 1315 1345 1415 1445 1518 Tynemouth Road/Howdon Lane ---- 0603 ---- 0700 0731 0758 0828 0901 0943 1018 1050 1120 1150 1220 1250 1320 1350 1420 1450 1523 Wallsend Metro <m> 0523 ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- Wallsend Forum d 0524 0611 ---- 0709 0741 0810 0841 0914 0955 1030 1100 1130 1200 1230 1300 1330 1400 1430 1500 1537 Dorset Avenue/West Street 0526 0615 ---- 0712 0744 0813 0844 0917 0958 1033 -

Northeast England – a History of Flash Flooding

Northeast England – A history of flash flooding Introduction The main outcome of this review is a description of the extent of flooding during the major flash floods that have occurred over the period from the mid seventeenth century mainly from intense rainfall (many major storms with high totals but prolonged rainfall or thaw of melting snow have been omitted). This is presented as a flood chronicle with a summary description of each event. Sources of Information Descriptive information is contained in newspaper reports, diaries and further back in time, from Quarter Sessions bridge accounts and ecclesiastical records. The initial source for this study has been from Land of Singing Waters –Rivers and Great floods of Northumbria by the author of this chronology. This is supplemented by material from a card index set up during the research for Land of Singing Waters but which was not used in the book. The information in this book has in turn been taken from a variety of sources including newspaper accounts. A further search through newspaper records has been carried out using the British Newspaper Archive. This is a searchable archive with respect to key words where all occurrences of these words can be viewed. The search can be restricted by newspaper, by county, by region or for the whole of the UK. The search can also be restricted by decade, year and month. The full newspaper archive for northeast England has been searched year by year for occurrences of the words ‘flood’ and ‘thunder’. It was considered that occurrences of these words would identify any floods which might result from heavy rainfall. -

North Tyneside Council Report to Cabinet Date: 12 November 2012

ITEM 7(l) North Tyneside Council Report to Cabinet Title: Flooding Task and Finish Group Date: 12 November 2012 Portfolio(s): Elected Mayor Cabinet Member(s): Mrs Linda Arkley Report from Directorate: Community Services Report Author: Paul Hanson Tel: (0191) 643 7000 Wards affected: All PART 1 1.1 Purpose: The purpose of the report is to inform Cabinet of the progress made so far by the Flooding Task and Finish Group; the emerging messages from its sub groups and explains proposed next steps. 1.2 Recommendation(s): It is recommended that Cabinet: (1) Note the information relating to the progress of the Flooding Task and Finish Group and its sub groups. (2) Note the proposed next steps of the Flooding Task Group and its sub groups. (3) Consider the virement of £0.096m Revenue funding and £0.092m Capital funding from the 2012/13 Area Forums environmental budget. (4) Agree the revised Council policy on Risk Management Approach to Flood Response. (5) Acknowledge the Council Motion of 25 October 2012 (per paragraph 1.5.6). (6) Agree that the Elected Mayor meet with Northumbria Water Limited to discuss the original development in the Preston Ward area. 1.3 Forward Plan: This report appears on the Forward Plan for the period 24 October 2012 to 28 February 2013. 1.4 Council Plan and Policy Framework This report relates to the following themes/programmes/projects in the Sustainable Community Strategy 2010-13: Quality of Life, Sense of Place, and to the following themes of the Council’s Performance Framework: Housing (Tenant Services), Health and Wellbeing, Street Scene. -

Copyright © Trapeze Group (UK)

North Shields-Northumberland Park-Cramlington-Ashington Go North East 19 Effective from: 05/09/2021 North ShieldsNorth FerryShields,Royal RudyerdQuaysPercy Outlet Street MainTyne Centre Metro Tunnel StationHigh Trading Flatworth,Silverlink Est Second ColbaltShopping Avenue BusinessCobalt Park BusinessParkNorthumberland South Park,Earsdon, Procter Park HolywellEarsdon & InterchangeGamble Village,RoadSeaton Delaval,MilbourneNSEC Hospital, Avenue Cramlington,Arms Head EastShankhouse, Cramlington DudleyBedlington, Lane Albion ShopsStakeford, TerraceFront StreetAshington Half West Moon Bus Station Approx. 5 11 14 16 17 20 22 24 31 35 39 43 49 56 62 70 81 89 journey times Monday to Friday North Shields Ferry .... .... 0727 0757 0827 0857 0927 0957 27 57 1457 1527 .... 1557 North Shields Ferry, Duke Street .... .... .... North Shields, Rudyerd Street arr .... .... 0730 0800 0830 0900 0930 1000 30 00 1500 1532 .... 1600 North Shields, Rudyerd Street dep .... .... 0730 0800 0830 0902 0932 1002 32 02 1502 1532 .... 1608 Royal Quays Outlet Centre .... .... 0736 0806 0836 0908 0938 1008 38 08 1508 1538 .... 1614 Percy Main Metro Station 0640 0700 0740 0810 0840 0911 0941 1011 41 11 1511 1541 .... 1617 Tyne Tunnel Trading Est 0642 0702 0742 0812 0842 0913 0943 1013 43 13 1513 1543 .... 1619 High Flatworth, Second Avenue 0643 0703 0743 0813 0843 0914 0944 1014 44 14 1514 1544 .... 1620 Silverlink Shopping Park 0646 0706 0746 0816 0846 0917 0947 1017 Then 47 17 1517 1547 .... 1623 Colbalt Business Park South 0648 0708 0748 0818 0848 0919 0949 1019 at 49 19 1519 1549 1610 1625 these Cobalt Business Park, Procter & Gamble 0649 0709 0749 0819 0849 0920 0950 1020 50 20 1520 1550 1612 1627 mins. -

Headquarters Office Building at Cobalt Park, Newcastle

30 TO LET/FOR SALE 63,507 sq ft (5,900 sq m) headquarters office building at Cobalt Park, Newcastle www.cobaltpark.co.uk Cobalt 30 63,507 sq ft (5,900 sq m) of outstanding office accommodation arranged over five, large open plan floors.This new building is prominently located adjacent the A19 offering occupiers superb branding opportunities. The building is currently finished to shell and core allowing the space to be fitted 30 out as Grade A office space or alternatively with exposed services providing a contemporary studio space. The building could also be suitable for alternative use such as hotel or services apartments subject to planning Location • Five diverse access and egress routes B • Future proofed against traffic congestion 1 B T 5 0 A H D A 5 A 1 O C E R 9 B K U 0 9 E . R 1 W Whitley Bay T A R S O A N A • Unrivalled public transport provision Golf Course W E D E T D R R 1 T E A O O S K F T R N S 9 T L L A I H R 3 A M N D D N E A L I Fordley N B K 1 DUDLEY S B B 1 3 2 1 3 5 1 2 2 3 2 A T 1 3 E RIV 1 D H 9 TON 1 KSEA N 9 MO E Accessibility B 2 A 30 D 1 Whitley Sands A A E 9 R O V 1 L East Holywell R I O 9 • Cobalt is connected to the local road network 9 A R A 8 N D 3 D 1 A E N Y O E via 5 separate access/egress routes - essential RRAD L U L B 8 I 4 D T N 1 A 1 R K to ensure free movement at peak times A A S H R O 5 West Holywell 9 0 B • Located on the A19 only 10 minutes drive 5 N A 3 1 1 O C B T 1 Burradon K A B Wellfield W T E E from central Newcastle R H A R O S S BACKWORTH D O 9 N K 8 L A N N T A 1 E 1 O 6 EARSDON 9 P A S 5 0 2 2 A I M E 1 3 2 M A B H B 1 D R • Incomparable access to the local road L T Camperdown A T K L C O R A R A N K W O A O Y O R A N 1 A E R F D W 9 WHITLEY BAY E N 3 network and national motorways. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 PDYP 2019. UPDATE.Qxp Layout 1 31/05/2019 11:41 Page 2

PDYP 2019._UPDATE.qxp_Layout 1 31/05/2019 11:41 Page 1 PHOENIX DETACHED YOUTH PROJECT Initiated by young people and MISSION creatively delivered STATEMENT Working with young people for young people to develop their ideas and supporting their life choices and education ANNUAL REPORT 2019 PDYP 2019._UPDATE.qxp_Layout 1 31/05/2019 11:41 Page 2 PROJECT PHOENIX DETACHED YOUTH FOREWORD The Phoenix Detached Youth Project celebrated its one of the trustees after having been 15th birthday last month. This is not only a wonderful supported by the project as a young achievement for the dedicated team who work at the person. Her insight will be invaluable to project, including Mike, who has been here since the the team. beginning, but also for the local community and the funders who have supported the project over this time. Our thanks go out to the wider PDYP team, the people who fund the work Part of this success has to be down to the fact that they and support us in so many ways, the have stayed true to their founding values, especially in mayor and our local councillors, the keeping the project manageable, local and maintaining the young people who give so much of their essential detached element of their work. It’s no secret that time and energy, our partner agencies, all our the past decade has been a difficult one for the youth work volunteers, our young ambassadors and the trustees. sector, through no fault of their own, projects come and go, We couldn’t do it without you! and young people and communities pay the price. -

Bishop Andrew Alexander Kenny Graham, RIP 1929-2021

INSIDE YOUR JUNE 2021 LINK: Page 2 Living in Love and Faith Page 4 Bishops’ pilgrimage Page 5 Meet our ordinands! Page 6 Lighthouse Project Page 7 Stolen Crucifix returned to church Page 9 Newcastle Generosity Week Bishop Andrew Alexander Kenny Graham, RIP 1929-2021 HE Diocese was very sad to op Alec’s full obituary will be published, grove has just been saying? I’m not at all hear of the death of Bishop however in the meantime, we are sure about it. Are you?” Alec Graham, who served as happy to share some tributes and fond the Bishop of Newcastle for 16 recollections from some of those who Idiosyncratic, characterful, intelli- years.T knew Bishop Alec during his time in gent, funny and kind - this was the Alec our Diocese. Graham so many of us admired and Bishop Alec died at his home in But- loved. terwick, supported by the excellent care The Very Revd Michael of those who have provided him with Sadgrove: Canon Alan Hughes: 24-hour nursing care over the last few In 1982, the Diocese of Newcastle Alec Graham’s dog Zillah interviewed years, on Sunday 9 May 2021. celebrated its centenary. Alec Graham me for the post at Berwick, she seated was its newly arrived bishop. That same on Alec’s chair, me on a sofa, Alec on Having previously been Suffragan year I arrived from the south as vicar of the floor, a scenario established during Bishop of Bedford, Bishop Alec was Alnwick. If anyone taught me to love his Oxford and Lincoln days.