Social Control Bolivia's New Approach to Coca Reduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The FARC and Colombia's Illegal Drug Trade

LATIN AMERICAN PROGRAM © JOHN VIZCANO/Reuters The FARC and Colombia’s Illegal Drug Trade By John Otis November 2014 Introduction In 2014, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, Latin America’s oldest and largest guerrilla army known as the FARC, marked the 50th anniversary of the start of its war against the Colombian government. More than 220,000 people have been killed1 and more than five million people uprooted2 from their homes in the conflict, which is the last remaining guerrilla war in the Western Hemisphere. However, this grim, half-century milestone coincides with peace negotiations between the Colombian government and the FARC that began in Havana, Cuba, in November 2012. The Havana talks have advanced much farther than the three previous efforts to negotiate with the FARC and there is a growing sense that a final peace treaty is now likely.3 So far, the two sides have reached agreements on three of the five points on the negotiating agenda, including an accord to resolve an issue that helps explain why the conflict has lasted so long: The FARC’s deep involvement in the taxation, production, and trafficking of illegal drugs. On May 16, 2014, the government and the FARC signed an agreement stating that under the terms of a final peace treaty, the two sides would work in tandem to eradicate coca, the plant used to make cocaine, and to combat cocaine trafficking in areas under guerrilla control. The FARC “has promised to effectively contribute, in diverse and practical ways, to a definitive solution to the problem of illegal drugs,” Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos said in a televised speech the day the accord was signed.4 “The Havana talks have advanced much farther than the three previous efforts to negotiate with the FARC and there is a growing sense that a final peace treaty is now likely.” A month later, Santos secured more time to bring the peace talks to a successful conclusion. -

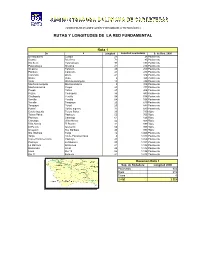

Rutas Y Longitudes De La Red Fundamental

GERENCIA DE PLANIFICACIÓN Y DESARROLLO TECNOLÓGICO RUTAS Y LONGITUDES DE LA RED FUNDAMENTAL Ruta 1 De A Longitud Longitud acumulada S. de Rod. 2006 Desaguadero Guaqui 24 24 Pavimento Guaqui Rio Seco 72 95 Pavimento Rio Seco Patacamaya 98 193 Pavimento Patacamaya Sicasica 21 214 Pavimento Sicasica Panduro 45 259 Pavimento Panduro Caracollo 24 283 Pavimento Caracollo Oruro 41 324 Pavimento Oruro Vinto 4 328 Pavimento Vinto Machacamarquita 18 346 Pavimento Machacamarquita Machacamarca 8 354 Pavimento Machacamarca Poopó 23 377 Pavimento Poopó Pazña 27 404 Pavimento Pazña Challapata 36 440 Pavimento Challapata Ventilla 94 534 Pavimento Ventilla Yocalla 64 598 Pavimento Yocalla Tarapaya 20 619 Pavimento Tarapaya Potosí 25 643 Pavimento Potosí Cuchu Ingenio 37 680 Pavimento Cuchu Ingenio Totora Palca 30 710 Ripio Totora Palca Padcoyo 55 765 Ripio Padcoyo Camargo 61 826 Ripio Camargo Villa Abecia 42 868 Ripio Villa Abecia El Puente 31 899 Ripio El Puente Iscayachi 54 953 Ripio Iscayachi Sta. Bárbara 40 993 Ripio Sta. Bárbara Tarija 12 1.005 Pavimento Tarija Cruce Panamericana 8 1.013 Pavimento Cruce Panamericana Padcaya 43 1.056 Pavimento Padcaya La Mamora 45 1.101 Pavimento La Mamora Emborozú 21 1.122 Pavimento Emborozú Limal 20 1.142 Pavimento Limal Km 19 52 1.194 Pavimento Km 19 Bermejo 21 1.215 Pavimento Resumen Ruta 1 Sup. de Rodadura Longitud 2006 Pavimento 902 Ripio 313 Tierra 0 Total 1.215 GERENCIA DE PLANIFICACIÓN Y DESARROLLO TECNOLÓGICO RUTAS Y LONGITUDES DE LA RED FUNDAMENTAL Ruta 2 De A Longitud Longitud acumulada S. de Rod. 2006 Kasani Copacabana 8 8 Pavimento Copacabana Tiquina 40 48 Pavimento Tiquina Huarina 37 85 Pavimento Huarina Río Seco 57 142 Pavimento El Alto La Paz 13 155 Pavimento Resumen Ruta 2 Sup. -

El Ceibo (Bolivia)

La Central de Cooperativas El Ceibo, la Política Nacional del Cacao y el Programa Nacional de Cacao Denominación Institucional El porqué del . Tomó este nombre por nombre? el árbol de nombre Ceibo (Erythrina poeppigiana) bastante común en la zona de producción. Es una Organización Cooperativa de Segundo grado que trabajan enmarcados bajo la Ley General de de Cooperativas de Bolivia. DATOS: Departamento de La Paz - Bolivia Provincias Caranavi, Sud Yungas y Larecaja, L.P. Ayopaya de Cbba. José Ballivián – Beni. A 270 km. de la ciudad de La Paz Temperatura promedio 25°C Precipitación media anual 1.800 mm Humedad relativa 70-80% Altitud 450m hasta 900m snm. DATOS GENERALES Aglutina a 48 cooperativas de base y 3 asociaciones (particulares) en 3 Municipios de La Paz (Palos Blancos, Teoponte y Alto Beni), 2 Municipios de Beni (Rurrenabaque y San Buenaventura) y Parte del Municipio de Ayopaya en Cochabamba. 1400 Productores de los cuales 1200 son socios y 200 particulares Certificamos aproximadamente 4.500 hectáreas de cacao. Un equipo técnico que evalua con mas de 30 selecciones locales de cacao, 6 son priorizadas. 4 7,000 6,000 Coch 5,000 Beni abam 9% ba 7% 4,000 Santa Cruz 3,000 1% 2,000 La 1,000 Pand o Paz 2% 81% 0 INE, 2016 5 Estimación de producción en grano seco en Alto Beni (Tn/año) 1600 1400 1380 1200 1391 1451 1415 1278 1233 1288 1000 1208 1182 1143 800 988 600 400 200 0 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Prod. CEIBO Producción TM Alto Beni 7 8 El 29 y 30 de noviembre del 2006 se realizó el 1er Congreso Nacional de Actores de la Cadena Productiva de Cacao de Bolivia, realizado en la localidad de Sapecho, del departamento de La Paz, a la cual asistieron 180 productores y recolectores de cacao. -

Turning Over a New Leaf: Regional Applicability of Innovative Drug Crop Control Policy in the Andes

TURNING OVER A NEW LEAF: REGIONAL APPLICABILITY OF INNOVATIVE DRUG CROP CONTROL POLICY IN THE ANDES Thomas Grisaffi, The University of Reading Linda Farthing, The Andean Information Network Kathryn Ledebur, The Andean Information Network Maritza Paredes, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú Alvaro Pastor, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú ABSTRACT: This article considers coca control and development strategies in Bolivia and Peru through the intersection of participatory development, social control and the relationship between growers and the state. Bolivia has emerged as a world leader in formulating a participatory, non-violent model in confronting the cocaine trade. Between 2006-2019 the government limited coca production through community-level control. Our study finds that not only has Bolivia’s model proven more effective in reducing coca acreage than repression, but it has effectively expanded social and civil rights in hitherto marginal regions. In contrast, Peru has continued to conceptualize ‘drugs’ as a crime and security issue. This focus has led to U.S.-financed forced crop eradication, putting the burden of the ‘War on Drugs’ onto impoverished farmers, and generating violence and instability. At the request of farmers, the Peruvian government is currently considering the partial implementation of the Bolivian model in Peru. Could it work? We address this question by drawing on long-term ethnographic fieldwork, interview data and focus group discussions in both countries, combined with secondary research drawn from government, NGO and international agency reports. We find that for community control to have a reasonable chance of success in Peru key areas need to be strengthened. These include the ability of grassroots organizations to self-police, building trust in the state through increased collaboration and incorporating coca growers into development and crop control institutions. -

Drugs and Development: the Great Disconnect

ISSN 2054-2046 Drugs and Development: The Great Disconnect Julia Buxton Policy Report 2 | January 2015 Drugs and Development: The Great Disconnect Julia Buxton∗ Policy Report 2 | January 2015 Key Points • The 2016 United Nations General Assembly Special Session on the World Drug Problem (UNGASS) will see a strong lobby in support of development oriented responses to the problem of drug supply, including from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). • The promotion of Alternative Development (AD) programmes that provide legal, non-drug related economic opportunities for drug crop cultivators reflects the limited success of enforcement responses, greater awareness of the development dimensions of cultivation activities and the importance of drugs and development agencies working co-operatively in drug environments. • Evidence from thirty years of AD programming demonstrates limited success in supply reduction and that poorly monitored and weakly evaluated programmes cause more harm than good; there has been little uptake of best practice approaches, cultivators rarely benefit from AD programmes, the concept of AD is contested and there is no shared understanding of ‘development’. • AD was popularised in the 1990s when development discourse emphasised participatory approaches and human wellbeing. This is distinct from the development approaches of the 2000s, which have been ‘securitised’ in the aftermath of the Global War on Terror and which re-legitimise military participation in AD. • UNGASS 2016 provides an opportunity for critical scrutiny of AD and the constraints imposed by the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs on innovative, rights based and nationally owned supply responses. Cultivation is a development not a crime and security issue. -

Datos De PTM 20200331

Tipo de PTM Nombre del Departamento Localidad Dirección Días de Atención Lunes a Viernes de PTM BOCA Punto Jhojoh Beni Guayaramerin Calle Cirio Simone No 512 Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM BOCA Centro de Beni Guayaramerin Avenida Gral Federico Roman S/N Esquina Calle Cbba Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM BOCA Centro de Beni Reyes Calle Comercio Entre Calle Gualberto Villarroel Y German Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM Central Jcell Beni Riberalta Avenida Dr Martinez S/N zona Central Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM BOCA Centro De Beni Yucumo Calle Nelvy Caba S/N Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM ELISA - Beni Santa Rosa de C/Yacuma S/N EsqComercio Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM BOCA Café Internet Beni Guayaramerin Calle Tarija S/N esquina Avenida Federico Roman Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM BOCA Café Internet Mary Beni San Borja Avenida Cochabamba S/N esquina Avenida Selim Masluf Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM BOCA Giros Mamoré Beni Trinidad Calle Teniente Luis Cespedez S/N esquina Calle Hnos. Rioja Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM Pulperia Tania Beni Riberalta Barrio 14 de Junio Avenida Aceitera esquina Pachuiba Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM Wester Union Beni Riberalta Av Chuquisaca No 713 Lado Linea Aerea Amazonas Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM Farmacia La Beni Trinidad Calle La Paz esquina Pedro de la Rocha Zona Central Lunes a Viernes 08:00 a 12:00 PTM BOCA Reyna Rosario Beni Riberalta C/ Juan Aberdi Entre Av. -

Planificación Estratégica

Ministerio de Planificación del Desarrollo Viceministerio de Planificación y Coordinación PROPUESTA DE PRESENTACIÓN MODELO PARA LA ETAPA DE SOCIALIZACIÓN PLANIFICACIÓN ESTRATÉGICA Febrero, 2017 AGENDA PATRIÓTICA 2025 . La Agenda Patriótica 2025 promulgada según Ley No. 650 de fecha 15-01-2015, plantea 13 Pilares hacia la construcción de una Bolivia Digna y Soberana, con el objetivo de levantar una sociedad y un Estado más incluyente, participativo, democrático, sin discriminación, racismo, odio, ni división. Los 13 Pilares se constituyen en los cimientos y fundamentos principales del nuevo horizonte civilizatorio para el Vivir Bien. PLAN DE DESARROLLO ECONÓMICO Y SOCIAL: 2016 - 2020 1 5 9 Soberanía ambiental con Soberanía comunitaria Erradicación de la pobreza desarrollo integral y financiera sin servilismo al extrema respetando los derechos de capitalismo financiero la Madre Tierra DESARROLLO INTEGRAL HACIA EL VIVIR BIEN… VIVIR EL HACIA INTEGRAL DESARROLLO 2 6 10 Integración Socialización y Soberanía productiva con universalización de los diversificación y desarrollo complementaria de los servicios básicos con integral sin la dictadura del pueblos con soberanía PDES soberanía para Vivir Bien mercado capitalista 2016-2020 Disfrute y felicidad 12 3 Soberanía sobre nuestros 7 recursos naturales con plena de nuestras fiestas, Salud, educación y deporte nacionalización, de nuestra música, para la formación de un industrialización y nuestros ríos, nuestra ser humano integral comercialización en armonía selva, nuestras montañas, y equilibrio con la Madre nuestros nevados, de Tierra nuestro aire limpio, de nuestros sueños 8 4 13 AGENDA PATRIÓTICA: 2025 PATRIÓTICA: AGENDA Soberanía alimentaria a Soberanía científica y través de la construcción del Reencuentro soberano con CONSTITUCIÓN POLÍTICA DEL ESTADO DEL POLÍTICA CONSTITUCIÓN tecnológica con identidad Saber Alimentarse para Vivir nuestra alegría, felicidad, propia Bien prosperidad y nuestro mar. -

An Economic Analysis of Coca Eradication Policy in Colombia

An Economic Analysis of Coca Eradication Policy in Colombia by Rocio Moreno-Sanchez David S. Kraybill Stanley R. Thompson1 Department of Agricultural, Environmental, and Development Economics The Ohio State University May 2002 Paper submitted for presentation at the AAEA Annual Meeting July 28 – 31, 2002, Long Beach, CA Abstract. We estimate an econometric model of coca production in Colombia. Our results indicate that coca eradication is an ineffective means of supply control as farmers compensate by cultivating the crop more extensively. The evidence further suggests that incentives to produce legal substitute crops may have greater supply- reducing potential than eradication. Key words: coca production, coca eradication, drug control policy 1 Graduate Assistant and Professors, respectively, in the Department of Agricultural, Environmental, and Development Economics at The Ohio State University. 2120 Fyffe Road, Columbus, OH 43210. Email: [email protected] Copyright 2002 by Rocio Moreno, David Kraybill, and Stanley Thompson. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies Introduction Coca (Erythroxylum coca) is the main input in the manufacture of cocaine hydrochloride, an addictive, pscyhostimulant drug whose use is illegal today in most countries. Policies regarding production and use of coca and its derivatives are controversial. The controversy focuses primarily on whether drug-control policies are effective in achieving their stated objectives of reducing cocaine usage. The Policy Setting Cocaine is produced in four stages: cultivation of the coca plant and harvesting of the leaf, extraction of coca paste, transformation of the paste into cocaine base, and conversion of the base into cocaine (Riley, 1993). -

Drug Supply Indicators

Working Paper Considering the Harms: Drug Supply Indicators Bryce Pardo RAND Drug Policy Research Center WR-1339 March 2020 Prepared for the Western Hemisphere Drug Policy Commission RAND working papers are intended to share researchers’ latest findings and to solicit informal peer review. They have been approved for circulation by RAND Social and Economic Well-Being but have not been formally edited or peer reviewed. Unless otherwise indicated, working papers can be quoted and cited without permission of the author, provided the source is clearly referred to as a working paper. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. is a registered trademark. Preface This working paper has been commissioned by the Western Hemisphere Drug Policy Commission, a Congressionally established body mandated to evaluate U.S. drug policies and programs in the Western Hemisphere with the aim of making recommendations to the President and Congress on the future of counter narcotics policies. The topic discussed in this manuscript deals with matters of drug supply- oriented policies and interventions with a particular focus on available supply-side indicators used to inform contemporary drug policy, the limits of those indicators, the future challenges of drug policy, and how to improve indicators such that they appropriately incorporate harms. Justice Policy Program RAND Social and Economic Well-Being is a division of the RAND Corporation that seeks to actively improve the health and social and economic well-being of populations and communities throughout the world. This research was conducted in the Justice Policy Program within RAND Social and Economic Well-Being. -

Download (2.95 MB )

“DUEÑAS DE NUESTRA VIDA, DUEÑAS DE NUESTRA TIERRA” Mujeres indígena originario campesinas y derecho a la tierra Pilar Uriona Crespo (Coordinadora de Investigación) Equipo de Investigación: Pelagio Pati Paco (Investigador responsable) Marina Patzy (Investigadora de apoyo) Jorge Loza (Investigador de apoyo) Coordinadora de la Mujer Dueñas de nuestra vida, dueñas de nuestra tierra. Mujeres indígena originario campesinas y derecho a la tierra / por Pilar Uriona Crespo (Coordinadora de Investigación), Pelagio Pati Paco (Investigador responsable), Marina Patzy (Investigadora de apoyo), Jorge Loza (Investigador de apoyo) La Paz, octubre de 2010, 146 p. Dueñas de nuestra VIDA, dueñas de nuestra TIERRA Mujeres indígena originario campesinas y derecho a la tierra Primera edición, octubre de 2010 Coordinadora de la Mujer Av. Arce Nº 2132, Edificio Illampu, piso 1, Of. “A” Telf./Fax: 244 49 22 – 244 49 23 – 244 4924 – 211 61 17 E-mail: [email protected] Página web: www.coordinadoramujer.org Casilla postal 9136 La Paz, Bolivia Depósito legal: 4-1-2413-10 ISBN: 978-99954-0-942-5 Cuidado de edición: Soraya Luján Diseño de tapas: Marcas Asociadas S.R.L. Diagramación: Alfredo Revollo Jaén Impresión: Impreso en Bolivia Printed in Bolivia ÍNDICE PresentacióN ................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 I. sITUANDO EL DEBATE........................................................................................................................................................................................... -

A Comparative Analysis of Two Tsimane ’ Territories in the Bolivian Lowlands

5 Indigenous Governance, Protected Areas and Decentralised Forestry: A Comparative Analysis of Two Tsimane ’ Territories in the Bolivian Lowlands Patrick Bottazzi1 Abstract The “territorial historicity” related to the Tsimane’ people living in the Boliv- ian lowlands is a complex process involving many governmental and non- governmental actors. The initiative of evangelist missionary organisations at the beginning of the 1990s led to the formal recognition of two Tsimane’ territories. While one territory was given a double status – Biosphere Reserve and indigenous territory – the other territory was put directly under the management of indigenous people. Elucidating the historical background of the process that led to the recognition and institutionalisation of the indig- enous territories enables us to understand that the constitution of an indig- enous political organisation remains a voluntary process justified above all by territorial strategies that have been mainly supported by foreign non- governmental organisations (NGOs). Thus, indigenous political leaders are currently struggling to take part in a more formal mechanism of territorial governance emerging from municipalities, governmental forestry services and forestry companies. Faced with the difficulty of reconciling the objec- tives related to conservation, development and democratisation, the differ- ent actors are using ethnic considerations to legitimise their positions. This leads to what we describe as “institutional segmentation”, a phenomenon that makes it difficult to set up a form of territorial planning capable of tak- ing into account the diversity of socio-ecological needs. We argue that the role of municipalities should be strengthened in order to better coordinate territorial management, following the diverse socio-ecological logics that exist in the area. -

Drug Crop Eradication and Alternative Development in the Andes

Order Code RL33163 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Drug Crop Eradication and Alternative Development in the Andes November 18, 2005 Connie Veillette Analyst in Latin American Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Carolina Navarrete-Frías Research Associate Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Drug Crop Eradication and Alternative Development in the Andes Summary The United States has supported drug crop eradication and alternative development programs in the Andes for decades. Colombia, Bolivia, and Peru collectively produce nearly the entire global supply of cocaine. In addition, Colombia has become a producer of high quality heroin, most of it destined for the United States and Europe. The United States provides counternarcotics assistance through the Andean Counterdrug Initiative (ACI). The program supports a number of missions, including interdiction of drug trafficking, illicit crop eradication, alternative development, and rule of law and democracy promotion. From FY2000 through FY2005, the United States has provided a total of about $4.3 billion in ACI funds. Since 2001, coca cultivation in the Andes has been reduced by 22%, with the largest decrease occurring in Colombia, according to the State Department. Opium poppy crops, grown mainly in Colombia and from which heroin is made, have been reduced by 67%. However, the region was still capable of producing 640 metric tons of cocaine, and 3.8 metric tons of heroin in 2004, according to the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy. Congress has expressed a number of concerns with regard to eradication, especially the health and environmental effects of aerial spraying, its sustainability and social consequences, and the reliability of drug crop estimates.