Edna Griffin and the Katz Drug Store Desegregation Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heraldry Examples Booklet.Cdr

Book Heraldry Examples By Khevron No color on color or metal on metal. Try to keep it simple. Make it easy to paint, applique’ or embroider. Blazon in layers from the deepest layer Per pale vert and sable all semy of caltrops e a talbot passant argent. c up to the surface: i v Field (color or division & colors), e Primary charge (charge or ordinary), Basic Book Heraldry d Secondary charges close to the primary, by Khevron a Tertiary charges on the primary or secondary, Device: An heraldic representation of youself. g Peripheral secondary charges (Chief,Canton,Border), Arms: A device of someone with an Award of Arms. n i Tertiary charges on the peropheral. Badge: An heraldic representation of what you own. z a Name field tinctures chief/dexter first. l Only the first word, the metal Or, B and proper nouns are capitalized. 12 2 Tinctures, Furs & Heraldic 11 Field Treatments Cross Examples By Khevron By Khevron Crosses have unique characteristics and specific names. Tinctures: Metals and Colors Chief Rule #1: No color upon another color, or metal on metal! Canton r r e e t t s i x e n - Fess - i D Or Argent Sable Azure Vert Gules Purpure S Furs Base Cross Latin Cross Cross Crosslet Maltese Potent Latin Cross Floury Counter-Vair Vair Vair in PaleVair-en-pointe Vair Ancient Ermine Celtic Cross Cross Gurgity Crosslet Fitchy Cross Moline Cross of Bottony Jerusalem A saltire vair in saltire Vair Ermines or Counter- Counter Potent Potent-en-pointe ermine Cross Quarterly in Saltire Ankh Patonce Voided Cross Barby Cross of Cerdana Erminois Field -

When Giraffes Attack! by Chris Dolunt

WHEN GIRAFFES ATTACK! BY CHRIS DOLUNT (This article first appeared in Game Trade Magazine West of Nyambe’s Giko Taaba mountain range lies the in 2002.) tUbI grassland, a nearly featureless expanse of savan- Encounter Level: 6 (mad giraffes); 8 (formian nah broken only by the occasional watering hole or taskmaster and bodyguard); 9 (formian warriors) tree. The grasses in the tUbI reach as tall as six feet in the most wild of regions, and provide sustenance to a Setting: The tUbI grassland on the continent of tremendous variety of animals, such as wildebeest and Nyambe-tanda — a tropical savannah or scrub plain. gazelle, upon which the fearsome lion-centaurs called Summary: The party is attacked by mad giraffes. the entare prey. The only people who regularly brave Unfortunately, the giraffes are the property of a the tUbI are those of the nomadic Shombe tribe, and formian hive. If the party kills the giraffes, the even they take pains to avoid the entare. formians demand compensation; what they really As the party travels through this grassland, they want is for the party to cure their animals. occasionally hear a strange whistling sound off in the Requirements: This encounter uses elements from distance. Eventually, the party catches sight of a the Nyambe: African Adventures campaign source- gigantic tree in the distance, hundreds of feet in book, coming in August 2002 from Atlas Games, but height. Before they can react to the sight, a nearby can be adapted to other campaign settings. It requires group of giraffes suddenly flies into a berserk rage that the party have some method of magically curing and charges the party! diseases; this could be a paladin, a character able to A few days ago, these giraffes were attacked by a mad cast remove disease, or a magic item capable of cast- lion, and although they survived the attack, they all ing it multiple times. -

8 Against Analytic Existence Entailments Peter Van Inwagen

8 Against Analytic Existence Entailments peter van inwagen 1 My purpose in this essay is to present arguments for the falsity of a central premise of Amie Thomasson’s meta-ontology: that there are such things as analytic existence entailments.* My task is made difficult by the fact that I can find in Thomasson’s work no examples of analytic existence entailments that strike me as actually having the features that such statements would have to have to do the work she wants them to do. Here is a sentence from Ordinary Objects1 that is supposed to be an example of an analytic existence entailment (‘analytic entailment’ means no more than that the condi- tional so described is an analytic proposition2; the “entailment” is from antecedent to consequent): If there are particles arranged chairwise, then there is a chair. (2007: 156)3 * I am grateful to Amie Thomasson for valuable and stimulating conversation and correspondence about the topics discussed in this essay. 1 Thomasson 2007: 156–7. In this essay, I discuss only the arguments of Ordinary Objects. Elsewhere (2016), I have examined (in the context of a wider examination of Thomasson’s meta-ontology) the similar arguments of her recent book Ontology Made Easy (2015). 2 Let us say that a sentence is analytic if a logically omniscient being who understood it perfectly would see, and would require no further resources to see, that it had to express a true proposition. Let us say that a proposition is analytic if it could be expressed by an analytic sentence. Thomasson devotes a significant proportion of Ordinary Objects to a defense of the thesis that (as I would phrase the thesis) there are analytic propositions. -

CURRICULUM VITAE NAME: Jonathan S. Gore PHONE

CURRICULUM VITAE NAME: Jonathan S. Gore PHONE: 859-622-1115 E-MAIL: [email protected] ADDRESS: 127 Cammack Building Eastern Kentucky University 521 Lancaster Avenue Richmond, Kentucky 40475 EDUCATION Ph.D. Psychology, May 2005 Minor: Statistics Iowa State University, Ames M.S. Psychology, May 2002 Iowa State University, Ames B.A. Psychology, May 1999 University of Michigan, Ann Arbor ACADEMIC POSITIONS June 2014 – present Director Office of Undergraduate Research Eastern Kentucky University August 2010 – present Associate Professor Department of Psychology Eastern Kentucky University August 2005 to August 2010 Assistant Professor Department of Psychology Eastern Kentucky University May 2005 to July 2005 Temporary Instructor Department of Psychology Iowa State University 1 TEACHING Course Prefix and Number Title Sections Taught PSY 200 Introductory Psychology 7 PSY 250/250W Information Literacy in Psychology 7 PSY 291/309/309W Statistical-Experimental I 16 PSY 300/300W Social Psychology 14 PSY 399 Research Development Skills 1 PSY 400 Psychology of Culture 5 PSY 402 Independent Work in Psychology 5 PSY 403 Practicum in Psychology 8 PSY 407 Problems in Psychology 5 PSY 510 & 710 Practicing and Publishing Empirical Research 4 PSY 837 Social Psychology and Cultural Diversity 14 PSY 862 Statistics and Research Design II 7 PSY 890 Thesis Research 3 ** Last updated Fall 2014 Additional Teaching Experience (Iowa State University) June 2005 to July 2005 Normal Personality May 2003 to June 2005 Research Design and Methodology August 2003 to May 2005 Research Methods in Psychology January 2003 to May 2003 Social Psychology August 2001 to December 2002 Psychological Measurement Lab May 2001 to July 2001 Motivation August 2000 to April 2001 Introduction to Psychology Lab August 1999 to April 2000 Academic Learning Skills 2 PUBLISHED WORKS Refereed Journal Articles: (Note: Underlined names denote EKU student coauthors) Gore, J. -

America Heraldica : a Compilation of Coats of Arms, Crests and Mottoes Of

rF t T. Jo Goolidge AMERICA HERALDICA A COMPILATION OF flits fl} |rnis, |ttsts aifl Jfltoea OF PROMINENT AMERICAN FAMILIES SETTLED IN THIS COUNTRY BEFORE 1800 EDITED BY E. DE V' VERMONT ILLUSTRATED BY AUGUSTE,LEROY- IRew JDorft THE AMERICA HERALDICA PUBLISHING ASSOCIATION 744 BROADWAY Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year i88g, by E. DB V. VERMONT, in the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. Ait rights reserved. Plates Engraved and Printed by Liebler & Maass, Letter-press by Haighl & Dudley, New York. Poughkeepsie. N. Y. ^r.,/,... AMERICA HERALDICA. PLATE I. gJUlVIRQSTOE VAK (o:\ 0]RTLftI2DT RCHEJ^ oy=ij=(is TTEftTHCOTE IJLIPSE VftB/teBSSELAElP^ CHVYLE]F^ OODHVLL %Aiy^AX .JilVJuKLEY JP^RKLIB OUTG^OmE'RY f^EUL> ^Bffi!^J\Y)^J^, PI NX. E. de V. VEJ^Orrr, Editor /^/^'^ ' / /}^-L. f-f"^-- / ^mi^^w- WI^Mmw'- AMERICA HERALDICA A COMPILATION OF Bits fit Irtus, psta aiil %'&iim OF PROMINENT AMERICAN FAMILIES SETTLED IN THIS COUNTRY BEFORE 1800 EDITED BY E. DE V. VERMONT ILLUSTRATED BY HENRY RYKERS BRENTANO BROTHERS lintcrcd, accuiiliili! in Act of Congress, in tll= year i8S6. by E. 1)K V. VKKMONT. in [he office of the Librarian of Congress, al Washington. W// / t^/ifs reserved. Letter-press by Haight Dudley, Kates Engraved and Printed hv The Hateh Lithographic Co., & Ponghkeepsie, N. Y. NewYorlj. AJJERICA HERAIiDICA Iniex of Colored Coats of Arms PI. Tlo. PI. No. Abereroinbie 19 1 Carpenter 16 14 Alexander 3 2 Carroll 9 2 " 17 2 Carter 20 9 Amory 4 1 Cary 9 12 " 17 1 Caverly 9 3 Anderson 5 1 Ghaloner 6 8 7 Andrews • • 6 1 Chandler 16 Appleton ••• 1 10 Chase 4 6 7 Archer • 1 3 Chauncey 6 Arnold 4 3 Chute 6 16 Bacon 9 1 Clarkson 14 8 Balche 13 10 Claytorne 9 4 Barclay 3 4 Clinton 3 7 Bard 15 6 Coddington 14 6 Barlcer 15 1 Coffin 4 4 Bartlett 15. -

Heraldic Device Consultation Sheet (PLEASE PRINT)

Heraldic Device Consultation Sheet (PLEASE PRINT) Client/Submitter Information Legal name: Address: City/State/Zip: Phone (Best Contact): ( Home, Cell, Work) E-mail: Gender: M F Date of birth: Do you have a registered name? Y N If yes, list: Do you have a profile established on Northshield.org? Y N Device Badge New Change Resubmission Date of Return: Reason for Return: Other (specify): _______________________________________________________________________________________________________ Local Group Name: Local herald: MDA: Consulting herald: MDA: Consultant’s Phone (Best Contact): ( Home, Cell, Work) Consultant’s E-mail: Client File Notes (for consulting herald use only): SCA Name (existing or proposed): New (with device submission) Already Registered - When and in what kingdom: In Process - When and in what kingdom: Heraldic Design: What is your favorite number and why? There are three tincture classifications: 1) colors, 2) metals and 3) furs. There are five colors: Azure (blue), Gules (red), Purpure (purple), Sable (black) and Vert (green). There are two metals: Argent (silver or white) and Or (gold or yellow). There are two basic fur types, of which there are color/metal variations: Ermine fur (metals with color spots & colors with metal spots) Vair fur (bell shaped quadrants composed of equal parts color and metal). METALS (Pick 1) COLORS (Pick 1 to 3) FURS (Pick 0 to 2) Argent (white) Azure (blue) Ermine (white/black spots) Vair (blue/white bell shapes) Or (yellow) Gules (red) Erminois (yellow/black spots) Vair variant (specify colors) Purpure (purple) Counter-ermine (black/white spots) Potent (blue/white “T”shapes) Sable (black) Pean (black/yellow spots) Potent Variant (specify colors) Vert (green) Ermine variant (specify colors) Ermine Counter Ermine Erminois Paen Vair Counter Vair Potent Counter Potent Charges (Objects client is interested in): Select up to three from each following category and list them below. -

The-Pursuivant-Of-Arms-Or-Heraldry-Founded-Upon-Facts.Pdf

600022745Q THE PURSUIVANT OF ARMS. i-y &JttHtmorial Gkt^ip^ .of Xnjm Beamfert Dttk of JStmo? i'iom Ms Garter Hale in S! @torg# Compel, Wratyi'tfr ^r Ji. Haxdmcfce, .192 Piccadilly. i»« April 1859." THE PURSUIVANT OF ARMS; OK, HERALDRY FOUNDED UPON EACTS. BY J. R. PLANCH E, Rouge Croix. " My attempt is not of presumption to teach (I myself having most need to be taught), but only to the intent that gentlemen who seek to know all good things and would have an entry into this, may not And here a thing expedient, but rather, a poor help thereto." Leigh's Accedence op Armorie. NEW EDITION. WITH ADDITIONS AND CORRECTIONS. LONDON: ROBERT HARDWICKE, 192, PICADILLY. AND ALL BOOKSELLERS. M<rq 2/<9. a,, 4-6- TO SIR CHARLES GEORGE YOUNG, Knt, GARTER KING OF ARMS, &c. &c. &c. DEAR SIR CHARLES, I have much pleasure in inscribing this little volume to you. + .„. A personal acquairi,tarice-""©f /nearly five and twenty years might, of itself, have entitled me to the privilege of thus expressing my respefct Jor an able antiquary, and esteem for a woTflpJ^mmi : but as Garter King of Arms, you have a double claim to this trifling tribute, independently of that of private friendship : Firstly, as the principal officer of a Corporation to which my best thanks are due for the courtesy of all, and the assistance of many of its members. Secondly, as one of that body, most competent to judge of the difficulties which beset the study of Heraldic Antiquities, and the real value of the results of such labour. -

Decoding Dexter

DECODING DEXTER: AN ANALYSIS OF AMERICA’S FAVORITE SERIAL KILLER by Erin Burns-Davies A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL August 2019 Copyright 2019 by Erin Burns-Davies ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Dr. Jane Caputi: Words fail to adequately express my gratitude for your participation as chair of my dissertation committee. Your scholarship, research suggestions, constructive criticism, patience, and belief in me were essential in making this manuscript a reality. I continue to be in awe of your work in ways that have not only influenced my writing but also my teaching. Dr. Marcella Munson: Your notes on my dissertation and feedback during my defense were critical in making the manuscript more polished and effective. Thank you for your participation on my dissertation committee. Dr. Christopher Robé: Thank you for your constructive criticism, particularly your insight into the connection between the horror genre and queer identity. I appreciate how your ideas have challenged and enhanced my work on this dissertation. My mother, Susan Burns-Davies: In your battle against cancer these last few years, you have been a model of bravery amidst hardship. Thank you for your many sacrifices and for seeing me to the end of this journey. I look forward to celebrating not only this achievement but also your renewed health and many years ahead with you by my side. Dr. Shireen Lalla: My sister, this project would not have been possible without your support. -

British Heraldry (1921)

BERKELEY / LIBRARY ^ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA J BRITISH HERALDRY BRITISH HERALDRY I, Arms of James I. 2, Great Seal of Scotland BRITISH HERALDRY CYRIL DAVENPORT V.D.. J.P., F.S.A. WITH 210 ILLUSTRATIONS BY TH^ AUTHOR NEW YORK E. P. DUTTON AND COMPANY PUBLISHERS Digitized by the Internet Arciiive in 2007 witii funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation littp://www.archive.org/details/britislilieraldryOOdavericli — CKicii CONTENTS CHAPTER I PAGE The Beginnings of Armory—The Bayeux Tapestry—Early Heraldic Manuscripts—The Heralds* College—Tourna- ments I CHAPTER n Shields and their Divisions— Colours a; d their Linear Repre- sentations as Designed by Silvestro Petra Sancta—Furs Charges on Shields— Heraldic Terms as to position and Arrangement of Charges—Marshalling—Cadency—How to Draw Up Genealogical Trees 13 CHAPTER HI Badges and Crests— List of Crests of Peers and Baronets, 191 2- 1920 53 CHAPTER IV Supporters—List of Supporters of Peers and Baronets, 1912- 1920 .143 CHAPTER V The Royal Heraldry of Great Britain and Ireland . 200 Index 217 166 — —— LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS rms of James I. Great Seal of Scotland . Frontispiece PAGE late I. Ancient Heraldry 2 I. English Shield from the Bayeux Tapestry—2. North American Tent with Armorial Totem—3. Rhodian Warrior with Armorial Shield 4. Standardof Duke William of Normandy— 5. Greek figure of Athene with Armorial Shield— 6. Norse Chessman with Armorial Shield 7. Standard of King Harold— 8. Norman Shield from the Bayeux Tapestry—9. Dragon Standard of Wessex. ate II. Divisions of Shields of Arms, etc 14 I. Paly—2. Bendy Sinister—3. Lozengy—4, Barry—5. -

February 2019 LORR Auroch’S Fjord 7685 Pufos Kimulega Per Pale Argent, Purpure and Sable, Shield a Wheel Sable and Two Roses Argent Barbed and Seeded Proper

Letter of Registration and Return February 2019 1 Greetings unto the populace of Adria! I would like to send a very special thank you to my team. Everyone of them is a volunteer that is putting in countless hours to make sure that your heraldry is correct, not in conflict, or just trying to help you create a new piece of art. The team includes: Sir Gerrit Van Gelder Dame Antonia Lopez‐Hawk AnRidire Ruaidhri Silverhand Dame Grainne Ni Mhaille Sir Mourngrym Dame Alistrina Lannoon Amragosso We have had a very busy month since we took over this department, and I am hoping I can show you our progress and continue to work on bringing us all up‐to‐date. Heraldry is a very important part of our culture as it brings pageantry and magic to what we do. Thank you to everyone that has so patiently been turning in their work so we can review it. We have had 66 submission so far!! Keep up the great work everyone! **If your heraldry does not appear here, please be patient, we are working on it, and should hopefully have it for you next month. ALL submission are to be sent directly through me please, [email protected] In service, Princess Gabriele Silverhand Imperial Sovereign of Arms 2 First order of business was bringing last year’s LORRs up‐to‐date on the website. I am pleased to say this is happening, thanks to the tireless efforts of Sir Gerrit and Dame Antonia. Please review and ensure that these are done correctly. -

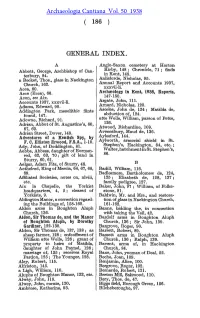

( 186 ) General Index

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 50 1938 ( 186 ) GENERAL INDEX. Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Horton Abbott, George, Archbishop of Can- Kirby, 148 ; Chronicle, 71 ; finds terbury, 84. in Kent, 148. a Becket, Thos., glass in Nackington Anlisforde, Nicholas, 95. Church, 162. Annual Report and Accounts 1937, Acca, 60. xxxvii-li. Acce (Ecca), 66. Archaeology in Kent, 1938, Reports, Aeon, see Aix. 147-150. Accounts 1937, xxxvii-li. Argate, John, 111. Adams, Edward, 90. Arnard, Nicholas, 120. Addington Park, mesolithic flints Asceles, John de, 124 ; Matilda de, found, 147. abduction of, 124. Adowne, Richard, 91. atte Welle, William, parson of Pette, Adrian, Abbot of St. Augustine's, 60, 126. 67, 69. Atwood, Richardine, 109. Adrian Street, Dover, 149. Avenesbury, Maud de, 136. Adventures of a Kentish Spy, by Aylesford, 144. F. C. Elliston Erwood, F.S.A., 1-10. Aylworth, armorial shield in St. Ady, John, of Doddington, 81. Stephen's, Hackington, 84, etc.; Aebba, Abbess, daughter of Eormen- Walter, hatchment in St. Stephen's, red, 62, 63, 70; gift of land in 86. Sturry, 60, 61. Aelgar, Adam Ktz, of Sturry, 48. B Aethelred, King of Mercia, 64, 67, 68, Badill, William, 116. 69. Badlesmere, Bartholomew de, 124, Affiliated Societies, notes on, xlviii, 125; Elizabeth de, 128, 137; etc. family pedigree, 127. Aix la Chapelle, the Yorkist Baker, John, 97 ; William, of Folke- headquarters, 4, 6; cleared of stone, 91. Yorkists, 9. Baldwin, Mr. and Mrs., and restora- Aldington Manor, a correction regard- tion of glass in Naokington Church, ing the Buildings of, 168-160. 161-162. Aldon arms in Boughton Aluph Banns, bidding the, in connection Church, 136. -

Georgia State Softball

2007 CAA Softball Championship (Final Four Setting) Thursday, May 10 Friday, May 11 Saturday, May 12 SITE: Hofstra Softball Stadium, Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y. SCHEDULE OF EVENTS Wednesday (May 9): Team Practices (Georgia State from 3:30-4:45 p.m.) Thursday (May 10): Noon - #4 UNC Wilmington (19-35, 9-12 CAA) at #1 Hofstra (37-13, 17-3 CAA) 3:30 p.m. - #2 James Madison (37-14, 17-3 CAA) vs. #3 Georgia State (32-28, 11-9 CAA) Friday (May 11): 10 a.m. - Game 3: Loser of Game 1 vs. Loser of Game 2 12:30 p.m. - Game 4: Winner of Game 1 vs. Winner of Game 2 3 p.m. - Game 5: Winner of Game 3 vs. Loser of Game 4 Saturday (May 12): Noon - Game 6: Winner of Game 4 vs. Winner of Game 5 CHAMPIONSHIP GAME Game 7: TEAM INFORMATION: If nec., begins 30 min. after Game 6 ends TICKET INFORMATION: Georgia State Atlanta, Ga. FREE ADMISSION 26,000 SPORTS INFORMATION OFFICE: Hofstra Hempstead, N.Y. (516) 463-6759 13,000 (516) 463-4933 James Madison Harrisonburg, Va. PRESS BOX PHONE: 16,900 (516) 523-6185 UNC Wilmington Wilmington, N.C. 12,000 CAA Softball Championship Bracket Thursday, May 10 Friday, May 11 Saturday, May 13 Day 1 Day 2 Finals Game 1 & 2 Game 3,4,5 Games 6 & 7 if necessary Hofstra Game 1 Winner G1 Noon UNC Wilmington Game 4 Winner G4 12:30 pm James Madison Game 2 Winner G2 3:30 pm CAA Georgia State Game 6 CHAMPION Noon Loser G1 If necessary Game 7 Game 3 Winner G3 10:00 am Loser G2 Game 5 Winner G5 3:00 pm Loser G4 Page 13 GEORGIA STATE SOFTBALL Probable Starting Line-Up 24 Danielle Roddy, 3B Freshman .349 12 2B, 0 3B, 3 HR, 21 RBI,