Monster Building Bo-Kaap Objections Comment And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cape Town's Film Permit Guide

Location Filming In Cape Town a film permit guide THIS CITY WORKS FOR YOU MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR We are exceptionally proud of this, the 1st edition of The Film Permit Guide. This book provides information to filmmakers on film permitting and filming, and also acts as an information source for communities impacted by film activities in Cape Town and the Western Cape and will supply our local and international visitors and filmmakers with vital guidelines on the film industry. Cape Town’s film industry is a perfect reflection of the South African success story. We have matured into a world class, globally competitive film environment. With its rich diversity of landscapes and architecture, sublime weather conditions, world-class crews and production houses, not to mention a very hospitable exchange rate, we give you the best of, well, all worlds. ALDERMAN NOMAINDIA MFEKETO Executive Mayor City of Cape Town MESSAGE FROM ALDERMAN SITONGA The City of Cape Town recognises the valuable contribution of filming to the economic and cultural environment of Cape Town. I am therefore, upbeat about the introduction of this Film Permit Guide and the manner in which it is presented. This guide will be a vitally important communication tool to continue the positive relationship between the film industry, the community and the City of Cape Town. Through this guide, I am looking forward to seeing the strengthening of our thriving relationship with all roleplayers in the industry. ALDERMAN CLIFFORD SITONGA Mayoral Committee Member for Economic, Social Development and Tourism City of Cape Town CONTENTS C. Page 1. -

Rainy Day in Cape Town!

Parker Cottage’s Suggestions for a Rainy Day in Cape Town! Yes, it’s true. It even rains in Cape Town! When it does, there are actually quite a few fun things you can do. No need to bury your head under the duvet and hibernate: get out there! Parker Cottage Tel +27 (21)424-6445 | Fax +27 (0)21 424-0195 | Cell +27 (0)79 980 1113 1 & 3 Carstens Street, Tamboerskloof, Cape Town, South Africa [email protected] | www.parkercottage.co.za The Two Oceans Aquarium … Whilst it’s not enormous, our aquarium is one of the nicest ones I’ve ever visited because of the interesting way it’s laid out. There is a shark tank, pressurized tanks for ultra-deep sea creatures and also a kelp forest tank (my favourite) complete with wave machine where you can watch the fish swimming inside an underwater forest. Check out the daily penguin and shark-tank feedings to see our beautiful creatures in hungry action, or visit the touch-pool for an interactive experience. The staff are also really fun and the place is well maintained and clean. Dig deep to find your inner child and you’ll enjoy. Open every day from 09h30 – 18h00. Shark feedings on Sundays at 15h00, and penguin feedings daily at 11h45 and 14h30. Parker Cottage Tel +27 (21)424-6445 | Fax +27 (0)21 424-0195 | Cell +27 (0)79 980 1113 1 & 3 Carstens Street, Tamboerskloof, Cape Town, South Africa [email protected] | www.parkercottage.co.za Indoor markets … Cape Town is no stranger to the concept of the market and the pop-up shop. -

Eat Visit Shop Stay Play

BEST OF CENTRAL CITY 2020 YOUR FREE COPY PLACES300 TO ENJOY IN THE CENTRAL CITY visit shop eat stay play MUSEUMS & BOUTIQUES, RESTAURANTS & HOTELS & BARS & CITY SIGHTS CRAFTS & ART COFFEE SHOPS BACKPACKERS NIGHT CLUBS Over 900 more places on our website. Visit capetownccid.org CapeTownCCID CapeTownCCID TO OBTAIN A COPY OF THIS MAGAZINE, CONTACT AZIZA PATANDIN AT THE CCID ON 021 286 0830 OR contents [email protected] ICONS TO NOTE WALLET- A SPECIAL WHEELCHAIR- CHILD- CLOSEST PARKING FRIENDLY TREAT OCCASION FRIENDLY FRIENDLY P (SEE PAGE 63) 5 17 27 visit shop eat Galleries, museums, city Fashion, gifts, décor Cafés, bakeries, sights and public spaces and books restaurants and markets 45 53 59 play stay essentials Theatres, pubs and Hotels and Useful info and clubs backpackers resources EDITORIAL EXECUTIVE TEAM Group Editor in Chief Sandy Welch Group Art Director Faranaaz Managing Director Aileen Lamb Commercial Director Maria Tiganis Rahbeeni Group Managing Editor Catherine Robb Project Manager Brand Strategy Director Andrew Nunneley Chief Financial Officer Wayne Cornelius Listings Writer Tracy Greenwood Printed by Novus Venette Malone Head of HR Camillah West CEO: Media24 Ishmet Print Davidson ADVERTISING PHOTOGRAPHY Getty Images, CCID, New Media, Iziko Museums of Key Account Manager SA, Pexels, Pixabay, Freepik, Unsplash, Scott Arendse, Ed Suter, Zaid Cheryl Masters | 021 417 1182 | Hendricks, RED! Gallery, Bocca, Mandela Rhodes Place, Signature Lux [email protected] Hotel, Cartel Rooftop Bar, Arcade, Reset, Fiction, Uncut Cover Image Unsplash/Banter Snaps PUBLISHING Group Account Director Raiël le Roux Production Manager Shirley Published by New Media, a division of Media24 (Pty) Ltd Quinlan New Media House, 19 Bree Street, Cape Town 8001 PO Box 440, Green Point 8051 Telephone +27 (0)21 417 1111 E-mail [email protected] www.newmedia.co.za DISCLAIMER New Media takes the utmost care to ensure all information in this magazine is correct at the time of going to print. -

Film Locations in TMNP

Film Locations in TMNP Boulders Boulders Animal Camp and Acacia Tree Murray and Stewart Quarry Hillside above Rhodes Memorial going towards Block House Pipe Track Newlands Forest Top of Table Mountain Top of Table Mountain Top of Table Mountain Noordhoek Beach Rocks Misty Cliffs Beach Newlands Forest Old Buildings Abseil Site on Table Mountain Noordhoek beach Signal Hill Top of Table Mountain Top of Signal Hill looking towards Town Animal Camp looking towards Devils Peak Tafelberg Road Lay Byes Noordhoek beach with animals Deer Park Old Zoo site on Groote Schuur Estate : External Old Zoo Site Groote Schuur Estate ; Internal Oudekraal Oudekraal Gazebo Rhodes Memorial Newlands Forest Above Rhodes Memorial Rhodes Memorial Rhodes Memorial Rhodes Memorial Rhodes Memorial Kramat on Signal Hill Newlands Forest Platteklip Gorge on the way to the top of Table Mountain Signal Hill Oudekraal Deer Park Misty Cliffs Misty Cliffs Tracks off Tafelberg Road coming down Glencoe Quarry Buffels Bay at Cape Point Silvermine Dam Desk on Signal Hill Animal Camp Cecelia Forest Cecelia Forest Cecilia Forest Buffels Bay at Cape Point Link Road at Cape Point Cape Point at the Lighthouse Precinct Acacia Tree in the Game camp Slangkop Slangkop Boardwalk near Kommetjie Kleinplaas Dam Devils Peak Devils Peak Noordhoek LookOut Chapmans Peak Noordhoek to Hout Bay Dias Beach at CapePoint Cape Point Cape Point Oudekraal to Twelve Apostles Silvermine Dam . -

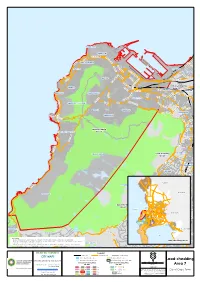

Load-Shedding Area 7

MOUILLE POINT GREEN POINT H N ELEN SUZMA H EL EN IN A SU M Z M A H N C THREE ANCHOR BAY E S A N E E I C B R TIO H A N S E M O L E M N E S SEA POINT R U S Z FORESHORE E M N T A N EL SO N PAARDEN EILAND M PA A A B N R N R D D S T I E E U H E LA N D R B H AN F C EE EIL A K ER T BO-KAAP R T D EN G ZO R G N G A KLERK E E N FW DE R IT R U A B S B TR A N N A D IA T ST S R I AN Load-shedding D D R FRESNAYE A H R EKKER L C Area 15 TR IN A OR G LBERT WOODSTOCK VO SIR LOWRY SALT RIVER O T R A N R LB BANTRY BAY A E TAMBOERSKLOOF E R A E T L V D N I R V R N I U M N CT LT AL A O R G E R A TA T E I E A S H E S ARL K S A R M E LIE DISTRICT SIX N IL F E V V O D I C O T L C N K A MIL PHILIP E O M L KG L SIGNAL HILL / LIONS HEAD P O SO R SAN I A A N M A ND G EL N ON A I ILT N N M TIO W STA O GARDENS VREDEHOEK R B PHILI P KGOSA OBSERVATORY NA F P O H CLIFTON O ORANJEZICHT IL L IP K K SANA R K LO GO E O SE F T W T L O E S L R ER S TL SET MOWBRAY ES D Load-shedding O RH CAMPS BAY / BAKOVEN Area 7 Y A ROSEBANK B L I S N WOO K P LSACK M A C S E D O RH A I R O T C I V RONDEBOSCH TABLE MOUNTAIN Load-shedding Area 5 KLIP PER N IO N S U D N A L RONDEBOSCH W E N D N U O R M G NEWLANDS IL L P M M A A A C R I Y N M L PA A R A P AD TE IS O E R P R I F 14 Swartland RIA O WYNBERG NU T C S I E V D CLAREMONT O H R D WOO BOW Drakenstein E OUDEKRAAL 14 D IN B U R G BISHOPSCOURT H RH T OD E ES N N A N Load-shedding 6 T KENILWORTH Area 11 Table Bay Atlantic 2 13 10 T Ocean R 1 O V 15 A Stellenbosch 7 9 T O 12 L 5 22 A WETTO W W N I 21 L 2S 3 A I A 11 M T E O R S L E N O D Hout Bay 16 4 O V 17 O A H 17 N I R N 17 A D 3 CONSTANTIA M E WYNBERG V R I S C LLANDUDNO T Theewaterskloof T E O 8 L Gordon's R CO L I N L A STA NT Bay I HOUT BAY IA H N ROCKLEY False E M H Bay P A L A I N MAI N IA Please Note: T IN N A G - Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this map at the time of puMblication . -

EMP) for Road Cycling and Mountain Biking: Table Mountain National Park (TMNP

Revision of the 2002 Environmental Management Programme (EMP) for Road Cycling and Mountain Biking: Table Mountain National Park (TMNP) compiled by SANParks and Table Mountain Mountain Bike Forum (TMMTB Forum) Draft for Public Comment MARCH 2016 Revision of the 2002 Environmental Management Programme – Cycling (Road and Mountain Bike) Document for Public Comment This document is the draft of the Revision of the 2002 Environmental Management Programme (EMP) for Road Cycling and Mountain Biking in the Table Mountain National Park. This document is an opportunity for interested parties, stakeholders and authorities to provide information and comment on this first draft which sets out how cycling will be managed in the Park. Where to find the EMP: Electronic copies, along with high resolution maps are available from the following websites: www.tmnp.co.za, www.TMMTB.co.za, www.pedalpower.org.za, www.amarider.org.za, www.tokaimtb.co.za Hard copies of the draft EMP have been placed at the following public libraries: Athlone Public Library Bellville Public Library Cape Town: Central Library Claremont Public Library Fish Hoek Public Library Grassy Park Public Library Gugulethu Public Library Hout Bay Public Library Khayelitsha Public Library Langa Public Library Mitchell's Plain Town Centre Library Mowbray Public Library Simon’s Town Public Library Tokai Public Library and the following Park offices: Boulders – Tokai Manor Kloofnek Office – Silvermine Office Simons Town House – Tokai Cape Town - Silvermine To ensure your submission is as effective as possible, please provide the following: • include name, organisation and contact details; • comment to be clear and concise; • list points according to the subject or sections along with document page numbers; • describe briefly each subject or issue you wish to raise; Comment period The document is open for comment from 04 April 2016 to 04 May 2016 Where to submit your comments [email protected] For attention: Simon Nicks Or, delivered to TMNP Tokai Manor Park office by 04th May 2016. -

Transmed Medical Fund Pharmacy Network List 2018

TRANSMED MEDICAL FUND PHARMACY NETWORK LIST 2018 Practice number Practice name Address Address Town Province 6005411 Algoa Park Pharmacy Algoa Park Shopping Centre St Leonards Road Algoapark Eastern Cape 6076920 Dorans Pharmacy 48 Somerset Street Aliwal North Eastern Cape Medi-Rite Pharmacy - 346292 Amalinda Shopping Centre Main Road Amalinda Eastern Cape Amalinda Shop 1 Major Square Cnr Avalon & Major Square 6003680 Beaconhurst Pharmacy Beacon Bay Eastern Cape Shopping Complex Road Clicks Pharmacy - Beacon Shop 26 Beacon Bay Retail 213462 Bonza Bay Road Beacon Bay Eastern Cape Bay Park Clicks Pharmacy - Cleary 192546 Shop 4 Cleary Park Centre Standford Road Bethelsdorp Eastern Cape Park Medi-Rite Pharmacy - Cnr Stanford & Norman 245445 Cleary Park Shopping Centre Bethelsdorp Eastern Cape Bethelsdorp Middleton Road Klinicare Bluewater Bay Shop 6-7 N2 City Shopping 95567 Hillcrest Drive Bluewater Bay Eastern Cape Pharmacy Centre 478806 Medirite Butterworth Fingoland Mall Umtata Street Butterworth Eastern Cape 6067379 Cambridge Pharmacy 18 Garcia Street Cambridge Eastern Cape 6082084 Klinicare Oval Dispensary 17 Westbourne Road Central Eastern Cape Provincial Westbourne 379344 84C Westbourne Road Central Eastern Cape Pharmacy 6005977 Rink Street Pharmacy 4 Rink Street Central Eastern Cape 376841 Klinicare Belmore Pharmacy 433 Cape Road Cotswold Eastern Cape Practice number Practice name Address Address Town Province 244732 P Ochse Pharmacy 17 Adderley Street Cradock Eastern Cape 6003567 Watersons Pharmacy Shop 4 Spar Complex Ja Calata Street -

Your Guide to Myciti

Denne West MyCiTi ROUTES Valid from 29 November 2019 - 12 january 2020 Dassenberg Dr Klinker St Denne East Afrikaner St Frans Rd Lord Caledon Trunk routes Main Rd 234 Goedverwacht T01 Dunoon – Table View – Civic Centre – Waterfront Sand St Gousblom Ave T02 Atlantis – Table View – Civic Centre Enon St Enon St Enon Paradise Goedverwacht 246 Crown Main Rd T03 Atlantis – Melkbosstrand – Table View – Century City Palm Ln Paradise Ln Johannes Frans WEEKEND/PUBLIC HOLIDAY SERVICE PM Louw T04 Dunoon – Omuramba – Century City 7 DECEMBER 2019 – 5 JANUARY 2020 MAMRE Poeit Rd (EXCEPT CHRISTMAS DAY) 234 246 Silverstream A01 Airport – Civic Centre Silwerstroomstrand Silverstream Rd 247 PELLA N Silwerstroom Gate Mamre Rd Direct routes YOUR GUIDE TO MYCITI Pella North Dassenberg Dr 235 235 Pella Central * D01 Khayelitsha East – Civic Centre Pella Rd Pella South West Coast Rd * D02 Khayelitsha West – Civic Centre R307 Mauritius Atlantis Cemetery R27 Lisboa * D03 Mitchells Plain East – Civic Centre MyCiTi is Cape Town’s safe, reliable, convenient bus system. Tsitsikamma Brenton Knysna 233 Magnet 236 Kehrweider * D04 Kapteinsklip – Mitchells Plain Town Centre – Civic Centre 245 Insiswa Hermes Sparrebos Newlands D05 Dunoon – Parklands – Table View – Civic Centre – Waterfront SAXONSEAGoede Hoop Saxonsea Deerlodge Montezuma Buses operate up to 18 hours a day. You need a myconnect card, Clinic Montreal Dr Kolgha 245 246 D08 Dunoon – Montague Gardens – Century City Montreal Lagan SHERWOOD Grosvenor Clearwater Malvern Castlehill Valleyfield Fernande North Brutus -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

Apartheid Space and Identity in Post-Apartheid Cape Town: the Case of the Bo-Kaap

Apartheid Space and Identity in Post-Apartheid Cape Town: The Case of the Bo-Kaap DIANE GHIRARDO University of Southern California The Bo-Kaap district spreads out along the northeastern flanks of cheaper housing, they also standardized windows and doors and Signal Hill in the shadow of CapeTown's most significant topograplucal eliminated the decorative gables and parapets typical of hgher income feature, Table Mountain, and overlooks the city's business &strict. areas.7 While the some of the eighteenth century terraces exhibited Accordmg to contemporary hstorical constructions, the district includes typical Cape Dutch detads such as undulating parapets, two panel portals, four areas - Schotschekloof, Schoonekloof, Stadzicht and the Old and fixed upper sash and movable lower sash windows, the arrival of Malay Quarter, but none of these names appear on official maps (except the British at the end of the eighteenth century altered the style once Schotschekloof, which is the official name for the entire area).' The again. Typical elements of Georgian architecture such as slim windows, first three were named after the original farmsteads which were paneled double doors and fanlights, found their way into housing of all transformed into residential quarters, Schoonekloof having been social classes, includng the rental housing in the BO-K~~~.~At the end developed in the late nineteenth century and Schotschekloof and of the nineteenth century, new housing in the Bo-Kaap began to include Stadzicht during and immediately following World War 11.' pitched roofs, bay windows, and cast iron work on balconies and Schotschekloof tenements - monotonous modernist slabs - were verandahs, at a time when a larger number of houses also became the erected for Cape Muslims during the 1940s as housing to replace slums property of the occupant^.^ A dense network of alleys and narrow, leveled as a result of the 1934 Slum Act. -

Aspects of the Structure, Tectonic Evolution and Sedimentation of The

ASPECTS OF THE STRUCTURE , TECTONIC EVOLUTION AND SEDIMENTATION OF THE TYGERBERG TERRANE, SOUTIDvESTERN CAPE PROVINCE . M.W. VON VEH . 1982 University of Cape TownDIGITISED 0 6 AUG 2014 A disser tation submitted to the Faculty of Science, University of Cape Town, for the degree of Master of Science. T VPI'l th 1 v.h le tJ t or m Y '• 11 • 10 uy the auth r. The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town ASPECTS OF THE ST RUCTURE, TECTONIC EVOLUT ION AND SEDIMENTATION OF THE TYGERBERG TE RRANE , SOUTI-1\VE STERN CAPE PROV I NCE. ABSTRACT A structural, deformational and sedimentalogical analysis of the Sea Point, Signal Hill and Bloubergstrand exposures of the Tygerberg Formation, Malmesbury Group, has been undertaken, through the application of developed geomathematical, digital and graphical computer-based techniques, encompassing the fields of tectonic strain determination, fold shape classification, cross-sectional profile preparation and sedimentary data representation. Emplacement of the Cape Peninsula granite pluton led to signi£icant tectonic shortening of the sediments, tightening of the pre-existing synclinal fold at Sea Point, and overprinting of the structure by a regional foliation. Strain determinations from deformed metamorphic spotting in the sediments yielded a mean , undirected A1 : A2: AJ value of 1.57:1.24:0.52. -

Phase One Archival Research Into the Block Bounded by Hudson, Dixon and Waterkant Streetsand Somerset Road, Cape Town

PHASE ONE ARCHIVAL RESEARCH INTO THE BLOCK BOUNDED BY HUDSON, DIXON AND WATERKANT STREETSAND SOMERSET ROAD, CAPE TOWN Prepared for Cape Quarter by Antonia Malan Historical Archaeology Research Group for the Archaeology Contracts Office, UCT, in conjunction with Aikman Associates November 2001 Background Propfin is proposing to develop a portion of the block by demolishing the existing structures, excavating for underground parking and building a thematic complex in the ‘Cape Quarter’ style to function as a retail centre. Propfin was advised by the Urban Conservation Unit of Cape Town City Council (CTCC) and the SA Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA) to undertake historical research into the block in conjunction with a professional heritage consultant. Henry Aikman approached the Archaeology Contracts Office at UCT (ACO) who undertook to prepare a preliminary archival report by 28 November 2001. The extent of the development includes erven 585, 586, 587, 588, 589 590, 607, 606, 605, 608, 602 (see noting sheets BH-7DB Y223 and Y224 dd 1963 (revised 1976)). A site inspection revealed that the internal lane, Vos Steeg, still exists and some of the original building fabric can still be seen. Previous experience of development in this area (e.g. the site of Long Life Lettering in Cobern Street) has also alerted the authorities to the possibility of impacting unmarked burial grounds. Brief The brief (see extract from letter from SAHRA to Propfin dd 2 October 2001 and letter from ACO to Propfin dd 14 November 2001) was: To examine the archival record in order to ascertain a chronological sequence for the properties and determine the extent of remaining historical fabric in the portions of the block under proposed development.