Tantifiers Firo B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Financial Therapy the Official Publication of the Financial Therapy Association

Journal of Financial Therapy The Official Publication of the Financial Therapy Association Volume 4, Issue 2 Editorial Offices Institute of Personal Financial Planning School of Family Studies and Human Services Kansas State University Manhattan, Kansas Journal of Financial Therapy Editor: Copyeditor: Kristy L. Archuleta, Kansas State University Megan R. Ford, University of Georgia Associate Editor of Profile and Book Reviews: Emily A. Burr, Kansas State University Editorial Board: Sonya Britt, Ph.D., CFP®, AFC® Eric J. Dammann, Ph.D. Jeff Dew, Ph.D. Kansas State University Psychoanalyst & Consultant Utah State University James M. Dodson, Psy.D. Jerry Gale, Ph.D., LMFT Joseph Goetz, Ph.D. AFC®, CRC© Clarksville Behavioral Health University of Georgia University of Georgia John Grable, Ph.D., CFP® James Grubman, Ph.D. Clinton Gudmunson, Ph.D. University of Georgia Family Wealth Consulting Iowa State University Sandra Huston, Ph.D. Soo-hyun Joo, Ph.D. Richard S. Kahler, M.S., CFP®, Texas Tech University Ewha Womans University, Korea Kahler Financial Group Brad Klontz, Psy.D. Joe W. Lowrance, Jr., Psy.D Wm. Marty Martin, Psy.D. Klontz Consulting Group Lowrance Psychology DePaul University Marcee Yager, CFP® Financial Vision LLC. Mailing Address: Institute of Personal Financial Planning School of Family Studies and Human Services 316 Justin Hall Kansas State University Manhattan, KS 66506 Phone: (785) 532-1474 Fax: (785) 532-5505 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.jftonline.org CC by 3.0 2013 Financial Therapy Association. Postmaster: Send address changes to Editor, Journal of Financial Therapy, 318 Justin Hall, Family Studies and Human Services, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506. -

March 29, 2021 Policy Division Financial Crimes Enforcement

March 29, 2021 Policy Division Financial Crimes Enforcement Network P.O. Box 39 Vienna, Virginia 22183 Re: FinCEN Docket Number FINCEN-2020-0020; RIN 1506-AB47; Requirements for Certain Transactions Involving Convertible Virtual Currency or Digital Assets Supplementary Submission To Whom It May Concern: Dash Core Group (“DCG”) appreciates the opportunity to submit this supplementary letter for consideration by the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (“FinCEN”) with respect to the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (“NPR”), published on December 23, 2020, titled “Requirements for Certain Transactions Involving Convertible Virtual Currency or Digital Assets.” See 85 FR 83840. Dash Core Group shared an initial letter on January 4, 2021 (https://www.regulations.gov/comment/FINCEN-2020-0020-7259), which is incorporated here. Due to the shortened comment period, we were unable to address in depth certain technical topics concerning CoinJoin, or to explore the specific implementation of CoinJoin on the Dash network as compared to what is available on Bitcoin. We address those issues here. In particular, we focus in this letter on the specific implementation of Dash’s CoinJoin solution branded “PrivateSend.” In recent communications with regulatory bodies, several have expressed the concern that the Dash network may somehow constitute a unique risk compared to other CoinJoin implementations because it is “built-in” or “part of the protocol.” This concept of CoinJoin being “built-in” is broad, vague, ambiguous, and open to many interpretations. Nevertheless, regardless of the specific interpretation, we will demonstrate that differentiating cryptocurrency privacy features based on the degree to which those features are “built-in” is not only arbitrary, but also irrelevant for assessing the risks associated with so-called “anonymity- enhanced cryptocurrencies” (or “AECs”). -

An Intersectional Exploration

BEING BLACK IN CORPORATE AMERICA An Intersectional Exploration SPONSORS Danaher, Interpublic Group, Johnson & Johnson, KPMG, Morgan Stanley, Pfizer, Unilever, The Walt Disney Company 1 Project team and sponsors RESEARCH PARTNER SPONSORS The Executive Leadership Council Danaher Ernest Adams RESEARCH LEADS Pooja Jain-Link, Executive Vice President Interpublic Group Julia Taylor Kennedy, Executive Vice President Heide Gardner PROJECT TEAM Johnson & Johnson Ngoc Duong, Research Intern Wanda Hope Isis Fabian, Manager, Research and Publications Pamela Fisher Emily Gawlak, Writer Tara Gonsalves, Researcher KPMG Silvia Marte, Manager, Communications Michele Meyer-Shipp Deidra Mascoll Idehen, Researcher Kevin Gilmore Laura Schenone, Vice President, Director of Communications and Marketing Faye Steele, Research Coordinator Morgan Stanley Emilia Yu, Research Associate Susan Reid Analia Alonso DESIGN TEAM Louisa Smith, Data Visualization and Illustration Pfizer Afsoon Talai, Creative Direction/Design Willard McCloud III Rachel Cheeks-Givan ADVISORS Trudy Bourgeois, Founder and CEO, The Center for Workforce Excellence Unilever Dr. Katherine Giscombe, Founder, Giscombe & Associates Mita Mallick Dr. Ella Bell Smith, Professor, Tuck School of Business, Dartmouth College Kamillah Knight Skip Spriggs, President and CEO, The Executive Leadership Council The Walt Disney Company Dr. Adia Harvey Wingfield, Professor of Sociology and Mary Tileston Hemenway Rubiena Duarte Professor in Arts & Sciences, Washington University in St. Louis © 2019 Center for Talent Innovation. All rights reserved. Unauthorized reproduction or transmission of any part of this publication in any form or by any means, mechanical or electronic, is prohibited. The findings, views, and recommendations expressed in Center for Talent Innovation reports are not prepared by, are not the responsibility of, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsoring companies or other companies in the Task Force for Talent Innovation. -

Lelantus Light Wallet Design Ideas Draft Version 0.0.6 (WIP)

Lelantus Light Wallet Design Ideas Draft Version 0.0.6 (WIP) www.firo.org March 2021 Abstract This note discusses light-wallet design ideas for Firo supporting both shielded and transparent transactions. 1 Introduction In order to receive coins or verify transactions the blockchain wallet needs to download the full ledger. This is not suitable for low capacity devices ( mobile wallets). A possible approach for supporting light-wallet functionality is the reliance on third-party [ Electrum ] services which can maintain the full ledger on behalf of the end users ( wallets) and provide and easy to use API to the wallets for accessing or filtering the transactions data. The drawback of this approach is this third-party service will get important information about the users transactions (its spending habits etc), so this is not acceptable for privacy reasons. Our light-wallet design enables the wallets to receive new coins or spend their coins by downloading only the anonymity set data along with other small block metadata and without relying on any semi- trusted third party services. This design leverages Firo's master nodes network and does not leak any spending or other transaction information to the nodes 2 Lelantus V1 Anonymity Sets 3 Lelantus V2 Anonymity Sets With Lelantus V2, the anonymity sets are comprised of pair values [C; Q], where each output coin C is explicitly associated with the corresponding recipient address Q. Each wallet can generate as many receiving addresses Q as he wants and the wallet can receive coins to the same address Q or to different addresses. -

Sun Shines Brightly on the Solar Industry Creating Value for Our

200/2017 Sun Shines Brightly on the Solar Industry / Page 6 Creating Value for Our Stakeholders / Page 14 First Metropolitan Network to Measure Air Quality / Page 24 Expanding to Vaporized Hydrogen Peroxide / Page 26 Vaisala in Brief Vaisala is a global leader in environmental and industrial measurement. Building on 80 years of experience, Vaisala contributes to a better quality of life by providing a comprehensive range of innovative observation and measurement products and services for chosen weather-related and industrial markets. Headquartered in Finland, Vaisala employs approximately 1,600 professionals worldwide and is listed on the NASDAQ Helsinki stock Contents 200/2016 exchange. Events & Webinars www.vaisala.com/events www.vaisala.com/webinars 3 Doing Good is Good Business Publishing Information 4 Over 100 Audits without a Single Published by: Vaisala Oyj Observation or Deviation P.O. Box 26 FI-00421 Helsinki FINLAND 6 Sun Shines Brightly on the Solar Industry Phone (int.): + 358 9 894 91 Internet: www.vaisala.com 8 Using Lightning Education and Data to Reduce Injuries and Fatalities in Agriculture Editor-in-Chief: Marina Stenfors Contributors: Katri Ahlgren, Anne 10 Reliable Measurements Helps Hänninen (CoComms), Francesca Davidson, Melanie Scott, Frank DeFina, Make Buildings Smarter Riika Pikkuvirta, Jon Tarleton, Tiina Vainio, Kati Andersin, Tomi Rintanen, 12 Practical Science – Vaisala Kirsi Linsuri-Sipilä and Tiina Kiianlehto Customers Turned Experts Cover photo: Shutterstock Design, Layout: Grapica Oy 14 Creating Value -

Successful Successions Sixty Townships Along the Connecticut River Tive Leadership Transitions

A S S O C I A T I O N O F C H I L D R E N ’ S M U S E U M S m no stranger to executive transitions in museums. In twenty years at five different institutions, I’ve experienced six leadership changes—including I’my own as the new(ish) executive director of the Montshire Museum of Science in Norwich, Vermont. I’ve seen the good and the bad sides of executive transitions, and I feel fortunate to be finishing up the first year of what I consider a successful succession. As a career professional in the museum per Valley, a loosely united group of some field, I have witnessed many forms of execu- Successful Successions sixty townships along the Connecticut River tive leadership transitions. A few times the Strategies for an Effective First Year between Vermont and New Hampshire. CEO was here today, gone tomorrow—with Marcos Stafne The founding director, Dr. Bob Chaffee, little notice to staff. In some instances, I was Montshire Museum of Science acquired a beloved collection of natural notified that a leader was going to retire or history objects from the then Dartmouth leave for personal reasons, and that a search College Museum. He used them to open or succession was going to take place—but I a community-supported science museum had little input or insight about the process. in a renovated bowling alley in Hanover, Once, I was deeply involved in a transition New Hampshire, hoping to ignite a passion process for a new CEO that involved meet- for the natural world and its sustainabil- ings with a search firm and detailedThe discus Lobby- Designing and Staffing for a “No-Free”ity. -

Investigating E-Servicescape, Trust, E-Wom, and Customer Loyalty

INVESTIGATING E-SERVICESCAPE, TRUST, E-WOM, AND CUSTOMER LOYALTY Gina A. Tran, B.A., B.S., M.S. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: David Strutton, Major Professor Kenneth Thompson, Committee Member Francisco Guzmán, Committee Member Robert Pavur, Committee Member Charles Blankson, PhD Program Coordinator Jeff Sager, Chair of the Department of Marketing and Logistics O. Finley Graves, Dean of the College of Business Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Tran, Gina A. Investigating E-Servicescape, Trust, E-WOM, and Customer Loyalty. Doctor of Philosophy (Marketing), August 2014, 112 pp., 27 tables, 5 figures, references, 278 titles. Old Spice cleverly used a handsome actor to play the Old Spice Man character for a Super Bowl commercial in 2010. After the game, this Old Spice commercial was viewed more than 13 million times on YouTube, a social media video-sharing site. This viral marketing campaign, also known as electronic word-of-mouth (E-WOM), propelled the Old Spice brand into the forefront of consumers’ minds, increased brand awareness, and inspired people to share the video links with their family, friends, and co-workers. The rapid growth of E-WOM is an indication of consumers’ increased willingness to convey marketing messages to others. However, despite this development, marketing academics and practitioners do not fully understand this powerful form of marketing. This dissertation enriches our understanding of E-WOM and how e-servicescape may lead to E-WOM. To that end, stimulus-organism-response theory and the network co-production model of E-WOM are applied to investigate the relationships between e-servicescape, trust, E-WOM intentions, customer loyalty, and purchase intentions. -

Lista Bug Bounty Programs

123 Contact Form DNSimple Listas Flexibles ReleaseWire 3DS OUTSCALE Donately (API) Livestream REM-B Hydraulics 8x8 Downstream Analytics lo arreglo Revertir 99Designs Dribbble Lob Revive Adserver Ábaco DRIVE.NET, Inc. Localize Rey Dragon Abacus Dropbox Localize Ribose Access router Dropcam LocalTapiola Ripple Acquia Dropmyemail Logentries Risk.io Active Campaign Drupal Logitech VDP Riskalyze ActiveProspect DuckDuckGo Loofah Robinhood ActiVPN eBay Lookout Roblox Adapcare Eclipse Lyst RoboCoin Adobe ecobee Mackepper Rocket.Chat AeroFS Ed MacOSX Bitcoin LevelDB Rockstar Games Aerohive eFront eLearning CMS Magdalena Romit aerolíneas Unidas eHealth Hub VZN KUL Magento (Ebay Inc) Royal Bank of Scotland Agora Ciudadana Security Electronic Arts (Games) Magix AG RSK Air Cloak EMC2 Mahara Ruby Airbnb Emptrust Mail.ru Ruby Language Airtable En efecto MailChimp Ruby on Rails Alcyon Enciphers Mailtime Technology Inc. RubyGems Maker Ecosystem Growth Algolia Endless Hosting Holdings, Inc Saas Híbrido Algorand Enebro ManageWP Salesforce Allegro Enecuum Mandrill App Samba Altervista Engineyard Mapbox Samsung Alvosec Envato MapLogin Samsung - Móviles Amara Enviado Marco Plone Samsung - Smart TV Amazon Web Services Eobot MariaDB savedroid Amitree Inc EOBOT BTC Marktplaats Saveya Marriott Vulnerability Análisis de riesgo Equifax Disclosure Program SAVIA Escuela independiente de Análisis descendente Millsap MasterCard VDP SBWire MasterCoin (+ ANCILE Solutions Inc. ESEA Herramientas) Schuberg Philis Android Free Apps ESLint Matomo Scorpion Software Anghami -

The Dusk Network Whitepaper

The Dusk Network Whitepaper Toghrul Maharramov Dmitry Khovratovich Dusk Network Dusk Network [email protected] [email protected] Emanuele Francioni Dusk Network [email protected] March 1, 2021 Version 3.0.0 Abstract This paper introduces a blockchain-based distributed ledger protocol called Dusk Network secured via a novel Proof-of-Stake-based consensus mechanism, enabling permission-less participation in the process of state transition execution, validation and addition to the global state while si- multaneously providing strong finality guarantees for the said state tran- sitions. The protocol is built to preserve privacy when transacting with the native protocol asset called DUSK and with native support of zero- knowledge proof-related primitives on the generalized compute layer. 1 Contents 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Our Contributions . 5 2 Overview 5 3 Use Cases 6 4 Notation 6 5 Abstract Protocol 8 6 Cryptographic Primitives 9 6.1 Hash Function . 9 6.2 Merkle Tree . 9 6.3 Elliptic Curve . 10 6.4 Stealth Address Scheme . 10 6.5 Encryption Scheme . 10 6.6 Commitment Scheme . 11 6.7 Signature Scheme . 11 6.8 Zero-Knowledge Proof Scheme . 12 7 Building Blocks 13 7.1 Segregated Byzantine Agreement . 13 7.1.1 Proof-of-Blind Bid . 15 7.1.2 Generation Phase . 17 7.1.3 Reduction Phase . 18 7.1.4 Agreement Phase . 19 7.1.5 Main Consensus Loop . 19 7.2 Phoenix . 20 7.3 Zedger . 22 7.4 Rusk VM . 23 7.5 Genesis Contracts . 25 7.5.1 DUSK Contract . 25 7.5.2 Bid Contract . -

Zcoin Is Becoming Firo – Zcoin

10/28/2020 Zcoin is becoming Firo – Zcoin English Get Zcoin About Blog Community Explorer Contact Crowdfunding ZCOIN BLOG Zcoin is becoming Firo By Reuben Yap October 27, 2020 No Comments Today, the team at Zcoin is pleased to announce its new name: Firo (ticker: XFR, pronounced “fee-roh”). Firo is not a new blockchain, but a new identity to differentiate ourselves and make nancial privacy more accessible to more people. Why is Zcoin changing its name to Firo? https://zcoin.io/zcoin-is-becoming-firo/ 1/6 10/28/2020 Zcoin is becoming Firo – Zcoin When Zcoin launched in 2016, we pioneered the use of the Zerocoin protocol. English Since that time, innovations by Zcoin and others have made that story less relevant Gete Zscpoeicnia llyA sbinocuet w eB nlogw u sCeo Smigmmuan aitnyd c uErrxepnlotlrye trra nCsiotinotnaicntg t oC Lreolwandtfuusn.ding Moreover, despite more than 4 years in the space, the similarity with Zcash is both confusing and misleading: though we both deal with privacy, they’re fundamentally different technologies, based on different priorities and values. The name ‘Firo’ was chosen for two reasons. First, it establishes a new metaphor of ‘burning’ coins and ‘redeeming’ them later. The concept of melting down coins and forging brand new ones is a great analogy to the way Lelantus works. Secondly, “Firo” sounds like money. Both of these are geared toward user-friendliness and mass adoption. Firo conjures up images of something aame and alive — consisting of re or burning strongly and brightly, the name is set to evoke a phoenix rising from the ashes. -

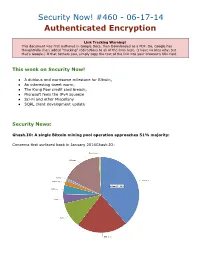

Security Now! #460 - 06-17-14 Authenticated Encryption

Security Now! #460 - 06-17-14 Authenticated Encryption Link Tracking Warning! This document was first authored in Google Docs, then Downloaded as a PDF. So, Google has thoughtfully (ha!) added “tracking” redirections to all of the links here. (I have no idea why, but that’s Google.) If that bothers you, simply copy the text of the link into your browser’s URL field. This week on Security Now! ● A dubious and worrisome milestone for Bitcoin, ● An interesting tweet worm, ● The Kung Pow credit card breach, ● Microsoft feels the IPv4 squeeze ● Sci-Fi and other Miscellany ● SQRL client development update Security News: Ghash.IO: A single Bitcoin mining pool operation approaches 51% majority: Concerns first surfaced back in January 2014Ghash.IO: ● What’s the problem? The “51% Attack” ● Bitcoin is a “decentralized” virtual currency… but what’s “decentralized” is the Proof of Work (PoW) processing power required to evolve the blockchain. ● If a single entity controls more than half of the entire network computing power, it could (not that it would, but it could) misbehave and break some of the assumptions inherent in the network’s decentralization. ● “Hacking, Distributed” blog, Friday the 13th, 2014: (two Cornell University researchers) http://hackingdistributed.com/2014/06/13/time-for-a-hard-bitcoin-fork/ ● A Bitcoin mining pool, called GHash and operated by an anonymous entity called CEX.io, just reached 51% of total network mining power today. Bitcoin is no longer decentralized. GHash can control Bitcoin transactions. Is This Really Armageddon? Yes, it is. GHash is in a position to exercise complete control over which transactions appear on the blockchain and which miners reap mining rewards.