Computer Games and the Aesthetic Practices of the Self: Wandering, Transformation, and Transfiguration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manny Diaz LEAD DESIGNER MANNYDIAZDESIGN.COM [email protected] LINKEDIN.COM

Manny Diaz LEAD DESIGNER MANNYDIAZDESIGN.COM [email protected] LINKEDIN.COM Award-Winning Lead Designer with international design development experience including: Design Direction, Design Management, Cross-Studio Collaboration, Mission Design, Scripting, Co-op and Multiplayer Ecosystems, Narrative and Combat Pacing, Chatter Writing, Cinematic Creation, Video Editing, Systems Tuning, Environmental Art, QuickTime Events, Spec Writing, Corporate & Industry Presentations, Film and Game Production Experience Ubisoft Reflections – Lead Level Designer Projects: Watch_Dogs, Tom Clancy’s The Division Time Line: June 2012 – Present Key Achievements: Lead team of 13 designers to deliver next-gen content on time and up to quality Developed implementation best practices for the design team Served as Interim Lead Game Designer Worked with Producers and Directors from co-development studios in Europe, Canada, and US Developed project schedule for design team Selected to represent Ubisoft in an international recruitment video Selected to represent Ubisoft Reflections at TIGA industry event Studio presentations in office and at external venues Video editing for studio presentation Volition Inc. – Design Director, Lead Mission Designer, and Designer 2 Projects: Saints Row: The Third, Saints Row: The Third DLC Packs, Unannounced Next-Gen Project Time Line: February 2010 – June 2012 Key Achievements: Directed three profitable projects to a delivery both on time and on budget Earned multiple awards and positive mentions in press for mission content Generated -

Xbox Cheats Guide Ght´ Page 1 10/05/2004 007 Agent Under Fire

Xbox Cheats Guide 007 Agent Under Fire Golden CH-6: Beat level 2 with 50,000 or more points Infinite missiles while in the car: Beat level 3 with 70,000 or more points Get Mp model - poseidon guard: Get 130000 points and all 007 medallions for level 11 Get regenerative armor: Get 130000 points for level 11 Get golden bullets: Get 120000 points for level 10 Get golden armor: Get 110000 points for level 9 Get MP weapon - calypso: Get 100000 points and all 007 medallions for level 8 Get rapid fire: Get 100000 points for level 8 Get MP model - carrier guard: Get 130000 points and all 007 medallions for level 12 Get unlimited ammo for golden gun: Get 130000 points on level 12 Get Mp weapon - Viper: Get 90000 points and all 007 medallions for level 6 Get Mp model - Guard: Get 90000 points and all 007 medallions for level 5 Mp modifier - full arsenal: Get 110000 points and all 007 medallions in level 9 Get golden clip: Get 90000 points for level 5 Get MP power up - Gravity boots: Get 70000 points and all 007 medallions for level 4 Get golden accuracy: Get 70000 points for level 4 Get mp model - Alpine Guard: Get 100000 points and all gold medallions for level 7 ghðtï Page 1 10/05/2004 Xbox Cheats Guide Get ( SWEET ) car Lotus Espirit: Get 100000 points for level 7 Get golden grenades: Get 90000 points for level 6 Get Mp model Stealth Bond: Get 70000 points and all gold medallions for level 3 Get Golden Gun mode for (MP): Get 50000 points and all 007 medallions for level 2 Get rocket manor ( MP ): Get 50000 points and all gold 007 medalions on first level Hidden Room: On the level Bad Diplomacy get to the second floor and go right when you get off the lift. -

Just Age Playing Around - How Second Life Aids and Abets Child Pornography Caroline Meek-Prieto

NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF LAW & TECHNOLOGY Volume 9 Article 6 Issue 3 Online Issue 10-1-2007 Just Age Playing Around - How Second Life Aids and Abets Child Pornography Caroline Meek-Prieto Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncjolt Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Caroline Meek-Prieto, Just Age Playing Around - How Second Life Aids and Abets Child Pornography, 9 N.C. J.L. & Tech. 88 (2007). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncjolt/vol9/iss3/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of Law & Technology by an authorized administrator of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF L-xw & TECHNOLOGY 9 NC JOLT ONLINE ED. 88 (2008) JUST AGE PLAYING AROUND? How SECOND LIFE AIDS AND ABETS CHILD PORNOGRAPHY Caroline Meek-Prieto' In 2002, Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition held that the possession, creation, or distribution of "virtual child pornography," pornography created entirely through computer graphics, was not a punishable offense because regualtion impermissibly infringed on the First Amendment right to free speech and did not harm real children. Only afew years after that decision, however, the Court's wisdom is being put to the test. A virtual world called Second Life, coupled with motion sensing technology, may provide a means for child pornographers to exploit real children while escaping detection. Second Life also provides a forum where users actively engage in sexual conduct with what appears to be a child. -

10 for $10 Pak Table of Contents Minimum System Requirements

10 FOR $10 PAK TABLE OF CONTENTS MINIMUM SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS ........................................................................ l WINDOWS 95 USERS...................................................................................................... 2 INSTALLATION ................................................................................................................ 2 STARTING A GAME ........................................................................................................ 3 USING THE ON-LINE DOCUMENTATION ................................................................ 4 CHUCK YEAGER'S AIR COMBAT.................................................................................. 6 EXTREME PINBALL ........................................................................................................ 6 THE COMPLETE ULTIMA VII ...................................................................................... 7 GRAND SLAM BRIDGE 11 . ............. ..... ........ ..... .................................. ..... ..... ..... ..... ........ 7 POPULOUS II .................................................................................................................. 8 POWERPOKER ................................................................................................................ 8 SEAL TEAM ...................................................................................................................... 9 STRIKE COMMANDER ................................................................................................. -

Demon's Souls Free Download Pc Demon’S Souls PC Download Free

demon's souls free download pc Demon’s Souls PC Download Free. Demon’s Souls Pc Download – Everything you need to know. Demon’s Souls is a best action role-playing game that is created by Fromsoftware that is available for the PlayStation 3. This particular game is published by Sony computer Entertainment by February 2009. It is associated with little bit complicated gameplay where players has to make the control five different worlds from hub that is well known as Nexus. It is little bit complicated game where you will have to create genuine strategies. It is your responsibility to consider right platform where you can easily get Demon’s Souls Pc Download. You will able to make the access of both modes like single player and multiplayer. It is classic video game where you will have to create powerful character that will enable you to win the game. All you need to perform the role of adventurer. In the forthcoming pargraphs, we are going to discuss important information regarding Demon’s Souls. Demon’s Souls Download – Important things to know. If you want to get Demon’s Souls Download then user should find out right service provider that will able to offer the game with genuine features. In order to win such complicated game then a person should pay close attention on following important things. Gameplay. Demon’s Souls is one of the most complicated game where you will have to explore cursed land of Boletaria. In order to choose a player then a person should pay close attention on the character class. -

Journal of Games Is Here to Ask Himself, "What Design-Focused Pre- Hideo Kojima Need an Editor?" Inferiors

WE’RE PROB NVENING ABLY ALL A G AND CO BOUT V ONFERRIN IDEO GA BOUT C MES ALSO A JournalThe IDLE THUMBS of Games Ultraboost Ad Est’d. 2004 TOUCHING THE INDUSTRY IN A PROVOCATIVE PLACE FUN FACTOR Sessions of Interest Former developers Game Developers Confer We read the program. sue 3D Realms Did you? Probably not. Read this instead. Computer game entreprenuers claim by Steve Gaynor and Chris Remo Duke Nukem copyright Countdown to Tears (A history of tears?) infringement Evolving Game Design: Today and Tomorrow, Eastern and Western Game Design by Chris Remo Two founders of long-defunct Goichi Suda a.k.a. SUDA51 Fumito Ueda British computer game developer Notable Industry Figure Skewered in Print Crumpetsoft Disk Systems have Emil Pagliarulo Mark MacDonald sued 3D Realms, claiming the lat- ter's hit game series Duke Nukem Wednesday, 10:30am - 11:30am infringes copyright of Crumpetsoft's Room 132, North Hall vintage game character, The Duke of industry session deemed completely unnewswor- Newcolmbe. Overview: What are the most impor- The character's first adventure, tant recent trends in modern game Yuan-Hao Chiang The Duke of Newcolmbe Finds Himself design? Where are games headed in the thy, insightful next few years? Drawing on their own in a Bit of a Spot, was the Walton-on- experiences as leading names in game the-Naze-based studio's thirty-sev- design, the panel will discuss their an- enth game title. Released in 1986 for swers to these questions, and how they the Amstrad CPC 6128, it features see them affecting the industry both in Japan and the West. -

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64 An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by James R. McAleese Janelle Knight Edward Matava Matthew Hurlbut-Coke Date: 22nd March 2021 Report Submitted to: Professor Dean O’Donnell Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. Abstract This project was an attempt to expand and document the Gordon Library’s Video Game Archive more specifically, the Nintendo 64 (N64) collection. We made the N64 and related accessories and games more accessible to the WPI community and created an exhibition on The History of 3D Games and Twitch Plays Paper Mario, featuring the N64. 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Table of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………………5 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 1-Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 2-Background………………………………………………………………………………………… . 11 2.1 - A Brief of History of Nintendo Co., Ltd. Prior to the Release of the N64 in 1996:……………. 11 2.2 - The Console and its Competitors:………………………………………………………………. 16 Development of the Console……………………………………………………………………...16 -

Chromehounds™

CH_XBOX360_MNLINT.qxp 4/28/06 10:43 AM Page 2 Thank you for purchasing Chromehounds™. Please note that this software is WARNING designed for use with the Xbox 360™ video game and entertainment system from Microsoft®. Be sure to read this software manual thoroughly before you start Before playing this game, read the Xbox 360™ Instruction Manual and any playing. peripheral manuals for important safety and health information. Keep all manuals for future reference. For replacement manuals see www.xbox.com/support or call Xbox Customer Support (see inside of back cover). TM Important Health Warning About Playing Video Games Photosensitive Seizures TABLE OF CONTENTS A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have BACKGROUND HISTORY . 2 an undiagnosed condition that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic NEROIMUS . 4 seizures” while watching video games. THE THREE NATIONS OF NEROIMUS . 4 These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, GETTING STARTED . 6 altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, CONNECT TO XBOX LIVE® . 6 disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also TITLE SCREEN . 7 cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling OPTIONS . 7 down or striking nearby objects. GAME CONTROLS . 8 SCREEN DISPLAYS . 10 Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Parents should watch for or ask their children about the above GARAGE. -

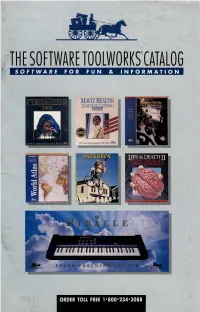

Thf SO~Twarf Toolworks®Catalog SOFTWARE for FUN & INFORMATION

THf SO~TWARf TOOlWORKS®CATAlOG SOFTWARE FOR FUN & INFORMATION ORDER TOLL FREE 1•800•234•3088 moni tors each lesson and builds a seri es of personalized exercises just fo r yo u. And by THE MIRACLE PAGE 2 borrowi ng the fun of vid eo ga mes, it Expand yo ur repertoire ! IT'S AMIRAClf ! makes kids (even grown-up kids) want to The JI!/ irac/e So11g PAGE 4 NINT!NDO THE MIRACLE PIANO TEACHING SYSTEM learn . It doesn't matter whether you 're 6 Coflectioll: Vo/11111e I ~ or 96 - The Mirttcle brings th e joy of music adds 40 popular ENT!RTA INMENT PAGE/ to everyo ne. ,.-~.--. titles to your The Miracle PiC1110 PRODUCTI VITY PAGE 10 Tet1dti11gSyste111, in cluding: "La Bamba," by Ri chi e Valens; INFORMATION PAGElJ "Sara," by Stevie Nicks; and "Thi s Masquerade," by Leon Russell. Volume II VA LU EP ACKS PAGE 16 adds 40 MORE titles, including: "Eleanor Rigby," by John Lennon and Paul McCartney; "Faith," by George M ichael; Learn at your own pace, and at "The Girl Is M in e," by Michael Jackson; your own level. THESE SYMBOLS INDICATE and "People Get Ready," by C urtis FORMAT AVAILABILITY: As a stand-alone instrument, The M irt1de Mayfield. Each song includes two levels of play - and learn - at yo ur own rivals the music industry's most sophis playin g difficulty and is full y arra nged pace, at your own level, NIN TEN DO ti cated MIDI consoles, with over 128 with complete accompaniments for a truly ENTERTAINMENT SYST!M whenever yo u want. -

Reality Is Broken a Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World E JANE Mcgonigal

Reality Is Broken a Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World E JANE McGONIGAL THE PENGUIN PRESS New York 2011 ADVANCE PRAISE FOR Reality Is Broken “Forget everything you know, or think you know, about online gaming. Like a blast of fresh air, Reality Is Broken blows away the tired stereotypes and reminds us that the human instinct to play can be harnessed for the greater good. With a stirring blend of energy, wisdom, and idealism, Jane McGonigal shows us how to start saving the world one game at a time.” —Carl Honoré, author of In Praise of Slowness and Under Pressure “Reality Is Broken is the most eye-opening book I read this year. With awe-inspiring ex pertise, clarity of thought, and engrossing writing style, Jane McGonigal cleanly exploded every misconception I’ve ever had about games and gaming. If you thought that games are for kids, that games are squandered time, or that games are dangerously isolating, addictive, unproductive, and escapist, you are in for a giant surprise!” —Sonja Lyubomirsky, Ph.D., professor of psychology at the University of California, Riverside, and author of The How of Happiness: A Scientific Approach to Getting the Life You Want “Reality Is Broken will both stimulate your brain and stir your soul. Once you read this remarkable book, you’ll never look at games—or yourself—quite the same way.” —Daniel H. Pink, author of Drive and A Whole New Mind “The path to becoming happier, improving your business, and saving the world might be one and the same: understanding how the world’s best games work. -

INSTRUCTION MANUAL 2.0 FSW PC Mnl UK.Qxd:2.0 FSW PC Mnl UK.Qxd 23.05.2007 14:45 Uhr Seite B

2.0_FSW_PC_Mnl_UK.qxd:2.0_FSW_PC_Mnl_UK.qxd 23.05.2007 14:45 Uhr Seite a INSTRUCTION MANUAL 2.0_FSW_PC_Mnl_UK.qxd:2.0_FSW_PC_Mnl_UK.qxd 23.05.2007 14:45 Uhr Seite b Table of Contents 2 MOUT: Military Operations in Urban Terrain 3 Your Soldiers 7 The Conflict 9 Reign of Terror 9 Geopolitical Intelligence Report: Zekistan 10 The HUD 12 Assessing the Environment 13 Commands Overview 15 Moving Your Soldiers 17 Fire Orders 19 Effects of Fire 20 Using Cover Against Threats 21 Grenades 23 Individual Fire Orders 23 Team Leader Tools 23 · Reporting with the Radio 24 · The Global Positioning System 25 · Saving your Progress 25 · Replays 25 · CASEVAC 26 · Profiles 26 · Mission Failure 27 Options 28 Co-operative Play 29 Online Menu 29 Online Options 31 Glossary 33 License Agreement 35 Register your Game! 35 Hints and Tips 35 Technical Support 36 Quickstart suomeksi 41 Quickstart på svenska 46 Credits 1 2.0_FSW_PC_Mnl_UK.qxd:2.0_FSW_PC_Mnl_UK.qxd 23.05.2007 14:45 Uhr Seite 2 MOUT: Military Operations in Urban Terrain MOUT: Military Operations in Urban Terrain You command a dismounted light infantry squad, a highly trained group Rifleman (R) of soldiers who understand how to operate in a hostile, highly populated The Rifleman has the least experience of soldiers on the fireteam, but don’t environment. Everything about your squad – from its soldiers to its underestimate him – he’s had extensive training. The Rifleman fires rounds equipment to its tactics – is the result of careful planning and years of from his M class rifle where you direct him, and he also gives aid to experience on the battlefield. -

Projectuality in Digital Gameworlds

Projectuality in Digital Gameworlds Daniel Vella University of Malta Msida, MSD2080, Malta [email protected] Stefano Gualeni University of Malta Msida, MSD2080, Malta [email protected] Keywords Phenomenology, existentialism, goals, projects, subjectivity, worldness INTRODUCTION With the objective of articulating an understanding of the existential structure of the player’s engagement with the gameworld, this paper draws on the notion of the ‘project,’ as developed in the existential philosophy of Martin Heidegger (1962[1927]) and, in particular, of Jean-Paul Sartre (1966[1943]). The existential notion of the project could generally defined as an orientation towards an overarching goal that, at its core, reveals the aspiration to shape one’s individual existence in a certain way. The project is an activity of self-determination – a process through which the individual works towards being “a certain type of person” (McInerney, 1979, 667). It is in the light of this projectual disposition that things are recognized as meaningful to the individual. It is because of that attitude that the things a player encounters in a gameworld are interpreted as important, secondary, pleasant, unpleasant, negligible, desirable, right, wrong, etc. The in-game project frames game entities as resources, obstacles, boundaries, friends, foes, and it is in this way that the digital game environment, as the player’s existential situation, takes the conscious form of a meaningful world of possibility. The paper’s exploration of the player’s engagement