Pay Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Optus Mobilesat® Digital Voice, Fax and Data

Optus MobileSat® Digital Voice, Fax and Data Guide to using Optus MobileSat services Optus is delighted to welcome you to a world first in mobile satellite phone communications. MobileSat has been designed and developed in Australia to offer a full range of voice, fax and data services, with national coverage extending up to 200kms out to sea. Please take a little time to familiarise yourself with this step-by-step introduction to using MobileSat services – and keep this guide in a convenient place for easy referral whenever you need it. Thank you for choosing Optus MobileSat. We look forward to keeping you in touch, from wherever you may by in Australia. Contents Optus Customer Service 1 Making and Receiving Calls 2 Operator and Emergency 3 Assistance Call Diversion 5 Fax & Data 7 VoiceMail 7 SureFax 10 Call Barring 13 Safety Precautions 15 Service and Repairs 16 Troubleshooting 17 Optus Customer Service As with all other Optus services, MobileSat is supported by our commitment to provide the highest standard of customer service. I Promises made to you are kept. I Customer Service representatives are courteous, efficient and professional in all their dealings with you. I Information given to you is accurate and complete. As a valued customer, you are our first priority, so if your queries can’t be answered in this guide, it’s good to know you can phone Customer Service for assistance. SUSPENDING SERVICE If for any reason you wish to temporarily suspend your MobileSat service, just call Optus Customer Service. Your monthly service charge for that month will be pro-rated for the period up until the day your service was suspended. -

Pay TV in Australia Markets and Mergers

Pay TV in Australia Markets and Mergers Cento Veljanovski CASE ASSOCIATES Current Issues June 1999 Published by the Institute of Public Affairs ©1999 by Cento Veljanovski and Institute of Public Affairs Limited. All rights reserved. First published 1999 by Institute of Public Affairs Limited (Incorporated in the ACT)␣ A.C.N.␣ 008 627 727 Head Office: Level 2, 410 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Phone: (03) 9600 4744 Fax: (03) 9602 4989 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ipa.org.au Veljanovski, Cento G. Pay TV in Australia: markets and mergers Bibliography ISBN 0 909536␣ 64␣ 3 1.␣ Competition—Australia.␣ 2.␣ Subscription television— Government policy—Australia.␣ 3.␣ Consolidation and merger of corporations—Government policy—Australia.␣ 4.␣ Trade regulation—Australia.␣ I.␣ Title.␣ (Series: Current Issues (Institute of Public Affairs (Australia))). 384.5550994 Opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily endorsed by the Institute of Public Affairs. Printed by Impact Print, 69–79 Fallon Street, Brunswick, Victoria 3056 Contents Preface v The Author vi Glossary vii Chapter One: Introduction 1 Chapter Two: The Pay TV Picture 9 More Choice and Diversity 9 Packaging and Pricing 10 Delivery 12 The Operators 13 Chapter Three: A Brief History 15 The Beginning 15 Satellite TV 19 The Race to Cable 20 Programming 22 The Battle with FTA Television 23 Pay TV Finances 24 Chapter Four: A Model of Dynamic Competition 27 The Basics 27 Competition and Programme Costs 28 Programming Choice 30 Competitive Pay TV Systems 31 Facilities-based -

Optus SMS Toolkit

Optus SMS Toolkit Integrate SMS Messaging into your existing software with SMS Toolkit. Email and SMS are two of the most powerful and popular communication tools in business today. Optus now gives your business the ability to enhance your applications by integrating SMS messaging into your existing software with SMS Toolkit. Developers and web designers can use the SMS Toolkit API to integrate SMS and messaging functionality into existing software. Enhance web sites, intranets or applications to send SMS/MMS* messages to and from over 130 countries. Build webs sites and applications that send reminders, alerts, leads and can deliver mobile content. Enhance your CRM solution with 2-way SMS messaging, MMS and Wap push. The SMS Toolkit provides all the tools required to build state-of-the-art mobile Internet, SMS or MMS solutions. FEATURES AND BENEFITS I SOAP/XML Web-Service API - a standard and popular programming interface. I Increases productivity by allowing businesses to automate existing systems with SMS functionality. I Provides easy to use interfaces for Microsoft and Unix/Linux as well as an extensive set of example source codes and documentation for VB.NET, C++ and PHP allowing you to reduce development time. I Code design using the latest development technology meaning reduced development costs. I Integration with existing software allows you to create your own value added services for customers and staff. I Royalty free with 4 hours of telephone support included. CUSTOMISATION AT YOUR FINGERTIPS SMS Toolkit is ideal for organisations looking to develop custom solutions or enhance existing software wIth SMS messaging functionality, without the need for additional customer-premise hardware. -

Optus Sustainability Report 2020 Our Highlights Contents

Optus Sustainability Report 2020 Our Highlights Contents 3 Our Company Strategy and Purpose 4 About Optus 5 About this Report 6 A Message from our Chairman and Chief Executive Officer 8 Supporting Resilience 13 The Most Connected Communities 27 Our Greatest Asset 38 The Best Experience 46 The Smallest Footprint 57 Addressing the Sustainable Development Goals 2 OVERVIEW THE MOST CONNECTED COMMUNITIES OUR GREATEST ASSET THE BEST EXPERIENCE THE SMALLEST FOOTPRINT ADDRESSING THE SDGS BCK FWD HOME Our Company Strategy and Purpose Engaging Digital Inclusion & our People Citizenship Wellbeing Climate At Optus we’re passionate about powering optimism Change & Education & Carbon Employment with options. We believe that nothing drives greater optimism than a company that operates sustainably to create lasting positive impact for its stakeholders and meet the present and future needs of society. Product Stewardship As a telecommunications company we believe we have a distinct and unique role to play in creating tomorrow’s world. Sustainability Our purpose helps us to think about the world we want Framework and embeds an ethos of innovation into our work. Our The Highest sustainability strategy is based on how we can harness Quality Service & Products our purpose and use our skills, resources and expertise to contribute to a better future for our customers, our people, the environment and our community. We focus The Best Ethical & on areas outlined in our sustainability framework where Talent Responsible we believe we can make a significant impact. Practices A Diverse & Health & Inclusive Safety Always Workship #1 Framework 3 OVERVIEW THE MOST CONNECTED COMMUNITIES OUR GREATEST ASSET THE BEST EXPERIENCE THE SMALLEST FOOTPRINT ADDRESSING THE SDGS BCK FWD HOME About Optus Optus is the second largest provider of telecommunications services in Australia in terms of revenue and employs more than 7,000 people nationally, who together are a reflection of our multicultural country and diverse customer base. -

The Media and Indigenous Policy

The Media and Indigenous Policy How news media reporting and mediatized practice impact on Indigenous policy A preliminary report Copyright © Kerry McCallum, Michael Meadows, Lisa Waller, Michelle Dunne Breen, Holly Reid, 2012 ISBN: 9781740883658 Editor: Associate Professor Kerry McCallum, Journalism & Communication Studies, Faculty of Arts & Design, University of Canberra Editorial Assistant: Monica Andrew Contributors: Kerry McCallum Michael Meadows Lisa Waller Michelle Dunne Breen Holly Reid Further information about the Australian News Media and Indigenous Policy-making 1988-2008 project is available at http://www.canberra.edu.au/faculties/arts-design/research/active- research-groups/public-communication/Indigenous-Policymaking This research was supported under the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Projects funding scheme (DP0987457), with additional funding supplied by the Faculty of Arts and Design, University of Canberra. ii Contents Acknowledgements v Executive summary vii Researchers ix Introduction 1 Media reporting and Indigenous policymaking 3 Kerry McCallum Policymaker perspectives 11 Managing the optics of Indigenous policy 13 Kerry McCallum & Lisa Waller When the stars align 23 Michael Meadows Media perspectives 33 Indigenous health reporting 1988–2008 34 Framing Indigenous Health, 1988–1995 37 Kerry McCallum Practice imperfect: media, discourse and intervention 43 Michelle Dunne-Breen Journalists, ‘remote’ Indigenous sources and cultural competence 51 Lisa Waller From little things big things grow: campaigning journalism -

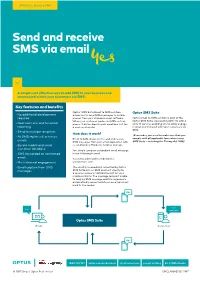

Send and Receive SMS Via Email

SMS Suite: Email to SMS Send and receive SMS via email . A simple cost effective way to add SMS to your business and communicate with your customers via SMS. Key features and benefits Optus’ SMS Suite Email to SMS solution Optus SMS Suite • No additional development allows you to send SMS messages to mobile required phones from your standard email software. Optus Email to SMS solution is part of the When your customer replies via SMS on their Optus SMS Suite, a powerful platform with a • Near real time and historical phone, it arrives back in your email box just like suite of services enabling you to easily engage, reporting a new email would. market and transact with your customers via SMS. • Send to multiple recipients How does it work? (Remember, you need to make sure that you • All SMS replies will arrive as comply with all applicable laws when using emails Email to SMS allows you to send and receive SMS messages from your email application with SMS Suite – including the Privacy Act 1988) • Build a mobile and email no additional software to install or manage. customer database You simply compose a standard email message • SMS forwardedSecurity to nominated Opinion Paper in the following format email +countrycodemobilenumber@sms. • Multi-channel engagement yourdomain.com. • Email capture from SMS The email is received and converted by Optus messages SMS Suite into an SMS and sent directly to a mobile number or distribution list for your mobile contacts. The message recipient is able to reply by SMS message and this response is automatically converted into an email and sent back to the sender. -

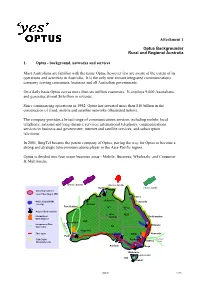

1. Optus - Background, Networks and Services

Attachment 1 Optus Backgrounder Rural and Regional Australia 1. Optus - background, networks and services Most Australians are familiar with the name Optus, however few are aware of the extent of its operations and activities in Australia. It is the only new entrant integrated communications company serving consumers, business and all Australian governments. On a daily basis Optus serves more than six million customers. It employs 9,000 Australians, and generates almost $6 billion in revenue. Since commencing operations in 1992, Optus has invested more than $10 billion in the construction of fixed, mobile and satellite networks (illustrated below). The company provides a broad range of communications services including mobile; local telephony; national and long distance services; international telephony; communications services to business and government; internet and satellite services; and subscription television. In 2001, SingTel became the parent company of Optus, paving the way for Optus to become a strong and strategic telecommunications player in the Asia-Pacific region. Optus is divided into four major business areas - Mobile; Business; Wholesale; and Consumer & Multimedia. B-Series Satellite A-Series Satellite Darwin C-Series Satellite Switching Systems/ Local Fibre Ring in CBD Cairns Mobile Digital(GSM) Katherine Townsville coverage Broome Port Hedland NT Mt Isa National Earth Stations Alice QLD International Springs Rockhampton Earth Station s WA S Geraldton International Fibre e M Brisbane e SA Optic Cable W e 3 Kalgoorlie Fibre Optic Port Augusta NSW Newcastle Perth SDH Digital Canberra Southern Sydney Microwave Link Cross VIC Adelaide Bega Melbourne Launceston TAS Hobart Optus 1 of 5 The company’s Mobile business unit has captured around one-third of the total Australian GSM mobile market and leads the market in mobile data take up. -

Countdown and Cult Music Television Programmes

Giuffre, Liz Countdown and Cult Music Television Programmes Countdown and cult music television programmes: an Australian case study Liz Giuffre Abstract Music television programs, programs that focus on music for their core content, have been produced all over the world for all types of markets. However there remains little sustained work on them beyond studies of key production periods, franchise waves or biography-like narratives. This article shows that theories of Cult TV can be applied to music television programs to help explore this neglected form, as well as helping to expand Cult TV’s theoretical reach beyond its traditional fare of narrative driven, fiction series. This article offers 1970s and ‘80s Australian music television program Countdown as a prime example of Cult TV, first in the context of its initial production and consumption in 1970s and ‘80s Australia, and also in terms of its subsequent influence on contemporary audiences from a historical perspective. The Cult TV frame extends to the program itself in its original incarnation, as well as additional recontextualisations in new music television programs, and the continued work of its former host, Ian ‘Molly’ Meldrum. Introduction1 Music television is an unusual type of programming. It provides both regular entertainment that is watched intensely while on air, and produces key moments that survive well in audience collective memory. ‘Live’ music performance and interview series Countdown remains an icon of the Australian television and music industries.2 Created by the national public service broadcaster, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC),3 the show was broadcast from 1974 to 1987 on Sunday evenings and was highly influential with television audiences and the broader music industry.4 Countdown provided opportunities for music artists and audiences to engage with each other in a way that had not previously been possible. -

Optus Recognises That Such an Approach, Whilst It Has Strong Policy Merit, Might Be Challenging Politically

Public Version | Page 1 Executive Summary 3 Developments in the sector have removed the need for a USO 5 Historical rationale of the USO 5 Current USO is a failed policy 7 There is no need for a USO 8 No justification for multiple sets of infrastructure to deliver USO 13 Retail competition over competitive infrastructure ensures supply 13 Current USO imposes high and untested costs 16 Extent of the current USO 16 Costs of the current USO 18 The USO distorts competition 22 Impact of USO on competitors 23 USO tax diverts competitive rural investment 25 Interaction with other government policies 25 Alternate USO policy options 27 A reformed USO should leverage off the NBN infrastructure 28 Promoting retail competition for provision of services 29 Keeping Telstra’s USO contractual position whole 31 Appendix A. Historic rationale of the USO 32 Appendix B. Issues Paper Questions 39 Public Version | Page 2 1.1 The Universal Service Obligation (USO) remains rooted in principles more applicable to the analogue era of telecommunications. It is predominantly focused on the delivery of fixed voice handsets and voice calls over fixed line copper connections. The widespread deployment and use of mobile, data and broadband services now render it increasingly inappropriate. 1.2 Three decades after the genesis of the USO the industry is vastly different from that which existed in the late 1980s: (a) Whilst Telstra retains a dominant position in the market, especially in regional Australia, competitive forces and regulation ensure that customers have access to genuine choice in a way that was not possible in the 1980s. -

Koori Engagement with Television by Gary Foley ©

Koori Engagement with Television by Gary Foley © In 1973 when television in Australia was still broadcast in black and white, the opening line of the first ever all-Aboriginal TV show was, "Welcome to colour television." Thus began the first attempt by indigenous Australians to come to terms with the advent of television into their world. For the Kooris television was always going to be far more problematic than for the white, Anglo-Celtic majority in Australia who already had been conditioned by the affluence and consumerist ideology and conceptual preparation transmitted to society through radio in the post- war era. In this essay I will explore indigenous community engagement with, and response to, the advent of television and subsequent attempts to both control and/or subvert the intent of television manufacturers and programmers. I will examine whether or not Aboriginal 'communities' in south-east Australia have succeeded in their efforts to limit what they perceive to be the culturally destructive effects of television in their respective communities. In Australia television was introduced around the country throughout the 1950s and 60s. The nation had been thoroughly prepared for the advent of television by massive publicity campaigns in the press and on the radio. Furthermore, radio had conditioned "white" Australia to naturalise concepts of modernity, domestic space and mass consumption, and thus prepared them for television's introduction. The fact that television programming (by virtue of its then predominantly American origin) communicated to the then patriarchal, white, nuclear family made it even easier for the dominant ideology in Australia to adjust. -

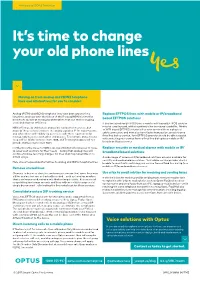

It's Time to Change Your Old Phone Lines

Analog and ISDN2 Transition It’s time to change your old phone lines . Moving on from analog and ISDN2 telephone lines and alternatives for you to consider. Analog (PSTN) and ISDN2 telephone lines have been around for a Replace EFTPOS lines with mobile or IP/broadband long time, and now with the rollout of the IP based NBN it’s time for businesses to look at moving to alternatives that can reduce ongoing based EFTPOS solutions costs and improve efficiency. If the line is just for EFTPOS then a mobile or IP based EFTPOS solution may be used instead, with the potential for increased useability. Mobile NBN offerings do still include analog line replacement services, but or WiFi based EFTPOS solutions free your terminal from a physical many of these services convert the analog signal to IP for transmission, cable connection, and may also have faster transaction speeds than a and while this is will reliably support voice calls there is potential for fixed line dial up service. Your EFTPOS provider should be able to assist interoperability issues with other end devices. Telstra have announced a with switching your service from a fixed line dial up to a mobile or IP/ ‘stop sell’ of ISDN2 services from 2018, and Telstra and Optus will not broadband based service. provide ISDN2 services over NBN. Furthermore the move to NBN is an opportunity for businesses to move Replace security or medical alarms with mobile or IP/ to lower cost solutions for their needs – noting that analog lines will broadband based solutions continue to have recurring charges, for lines that may have little or no actual usage. -

Pager Configuration

Appendix A: Pager Configuration A.1 Overview of Pager Services Configuration The Multimedia Configurator offers a Pager Agent that connects to a wide variety of pager services and supports the most popular paging protocols: • Tele Alphanumeric Protocol (TAP) • Simple Messaging Service (SMS) Other variations are supported as well, such as Paging Entry Terminal (PET), which is basically the same as TAP. The method through which a page is sent depends on the type of pager being used. For example, in the United States the predominant pager type uses TAP and uses a standard modem to communicate. TAP pagers can also use Integrated Services Digital Network (ISDN) carriers. The Multimedia Configurator user interface calls out the use of “Modem/ISDN Service” (rather than specifying actual protocols used), as this is more straightforward for users to understand. Note: It is the paging service and the Multimedia software that communicate via TAP; it is not something special in the modem itself. Therefore, most “Hayes® compatible” off-the-shelf modems should work for sending TAP messages. SMS pagers offer more sophisticated interaction. For example, they permit two-way paging. In the case of Multimedia, this allows users to send an “Acknowledge” back to the alarm system directly from the pager. SMS paging messages are not sent over a modem, but rather use the Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM) network. Again, rather than calling out the low-level protocols used, the Multimedia Configurator interface refers to the method of communication, and calls this “GSM/PCS Service”. A.1.1 Installation During the installation of M-Alarm Multimedia (MMX), after checking the box to include the Pager Agent, you can select which paging services to include with the installation.