Optus Recognises That Such an Approach, Whilst It Has Strong Policy Merit, Might Be Challenging Politically

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Optus Mobilesat® Digital Voice, Fax and Data

Optus MobileSat® Digital Voice, Fax and Data Guide to using Optus MobileSat services Optus is delighted to welcome you to a world first in mobile satellite phone communications. MobileSat has been designed and developed in Australia to offer a full range of voice, fax and data services, with national coverage extending up to 200kms out to sea. Please take a little time to familiarise yourself with this step-by-step introduction to using MobileSat services – and keep this guide in a convenient place for easy referral whenever you need it. Thank you for choosing Optus MobileSat. We look forward to keeping you in touch, from wherever you may by in Australia. Contents Optus Customer Service 1 Making and Receiving Calls 2 Operator and Emergency 3 Assistance Call Diversion 5 Fax & Data 7 VoiceMail 7 SureFax 10 Call Barring 13 Safety Precautions 15 Service and Repairs 16 Troubleshooting 17 Optus Customer Service As with all other Optus services, MobileSat is supported by our commitment to provide the highest standard of customer service. I Promises made to you are kept. I Customer Service representatives are courteous, efficient and professional in all their dealings with you. I Information given to you is accurate and complete. As a valued customer, you are our first priority, so if your queries can’t be answered in this guide, it’s good to know you can phone Customer Service for assistance. SUSPENDING SERVICE If for any reason you wish to temporarily suspend your MobileSat service, just call Optus Customer Service. Your monthly service charge for that month will be pro-rated for the period up until the day your service was suspended. -

Pay TV in Australia Markets and Mergers

Pay TV in Australia Markets and Mergers Cento Veljanovski CASE ASSOCIATES Current Issues June 1999 Published by the Institute of Public Affairs ©1999 by Cento Veljanovski and Institute of Public Affairs Limited. All rights reserved. First published 1999 by Institute of Public Affairs Limited (Incorporated in the ACT)␣ A.C.N.␣ 008 627 727 Head Office: Level 2, 410 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Phone: (03) 9600 4744 Fax: (03) 9602 4989 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ipa.org.au Veljanovski, Cento G. Pay TV in Australia: markets and mergers Bibliography ISBN 0 909536␣ 64␣ 3 1.␣ Competition—Australia.␣ 2.␣ Subscription television— Government policy—Australia.␣ 3.␣ Consolidation and merger of corporations—Government policy—Australia.␣ 4.␣ Trade regulation—Australia.␣ I.␣ Title.␣ (Series: Current Issues (Institute of Public Affairs (Australia))). 384.5550994 Opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily endorsed by the Institute of Public Affairs. Printed by Impact Print, 69–79 Fallon Street, Brunswick, Victoria 3056 Contents Preface v The Author vi Glossary vii Chapter One: Introduction 1 Chapter Two: The Pay TV Picture 9 More Choice and Diversity 9 Packaging and Pricing 10 Delivery 12 The Operators 13 Chapter Three: A Brief History 15 The Beginning 15 Satellite TV 19 The Race to Cable 20 Programming 22 The Battle with FTA Television 23 Pay TV Finances 24 Chapter Four: A Model of Dynamic Competition 27 The Basics 27 Competition and Programme Costs 28 Programming Choice 30 Competitive Pay TV Systems 31 Facilities-based -

Telecommunications Infrastructure Support Guide

Telecommunications Infrastructure Support Guide Making the most of the nbn and the Mobile Black Spot Program First Edition — October 2016 A NSW Government Initiative Front Cover: Ed Fagan, Cowra Address & Contact Details Photo: Kate Barclay Suite 4, 59 Hill Street First Edition published in 2016 by Regional Development Australia (PO Box 172) Central West, Orange, NSW. ORANGE NSW 2800 02 6369 1600 This publication is copyright. Apart from any fair use as permitted under the Copyright www.rdacentralwest.org.au Act 1968, no part may be produced by any process without permission from the publisher. All For any questions relating to this guide or the information Rights Reserved. contained herein, please feel free to contact RDA Central West and we will endeavour to provide assistance where possible. Disclaimer: Information provided in this publication is intended as a general reference and is provided About Regional Development Australia Central West in good faith. It is made available on the understanding that Regional Development Australia RDA Central West is a Commonwealth and State funded not-for- Central West is not engaged in rendering professional advice. profit organisation responsible for the economic development and long term sustainability of the NSW Central West region. Regional Development Australia Our organisation is overseen by a Committee of dedicated local Central West makes no leaders who possess a wide cross section of professional skills and statements, representations, or warranties about the accuracy experience. or completeness -

State of Mobile Networks: Australia (November 2018)

State of Mobile Networks: Australia (November 2018) Australia's level of 4G access and its mobile broadband speeds continue to climb steadily upwards. In our fourth examination of the country's mobile market, we found a new leader in both our 4G speed and availability metrics. Analyzing more than 425 million measurements, OpenSignal parsed the 3G and 4G metrics of Australia's three biggest operators Optus, Telstra and Vodafone. Report Facts 425,811,023 31,735 Jul 1 - Sep Australia Measurements Test Devices 28, 2018 Report Sample Period Location Highlights Telstra swings into the lead in our download Optus's 4G availability tops 90% speed metrics Optus's 4G availability score increased by 2 percentage points in the A sizable bump in Telstra's 4G download speed results propelled last six months, which allowed it to reach two milestones. It became the the operator to the top of our 4G download speed and overall first Australian operator in our measurements to pass the 90% threshold download speed rankings. Telstra also became the first in LTE availability, and it pulled ahead of Vodafone to become the sole Australian operator to cross the 40 Mbps barrier in our 4G winner of our 4G availability award. download analysis. Vodafone wins our 4G latency award, but Telstra maintains its commanding lead in 4G Optus is hot on its heels upload Vodafone maintained its impressive 4G latency score at 30 While the 4G download speed race is close among the three operators milliseconds for the second report in row, holding onto its award in Australia, there's not much of a contest in 4G upload speed. -

Perth Public Hearing Transcript

__________________________________________________________ PRODUCTIVITY COMMISSION INQUIRY INTO THE TELECOMMUNICATIONS UNIVERSAL SERVICE OBLIGATION MR P LINDWALL, Presiding Commissioner TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS AT PERTH ON TUESDAY, 14 FEBRUARY 2017 AT 8.43 AM Telecommunications 14/02/17 1 © C’wlth of Australia INDEX Page MR BRUCE BEBBINGTON 4-7, 88 MIDWEST DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION MR ROBERT SMALLWOOD 17-31 SHIRE OF CUBALLING MR GARY SHERRY 32-37 REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT AUSTRALIA WHEATBELT MS JULIET GRIST 37-46, 87-88 MEMBER FOR AGRICULTURAL REGION THE HON. MARTIN ALDRIDGE MLC 46-55 GREAT NORTHERN TELECOMMUNICATIONS MR ANDREW MANGANO 55-63 SHIRE OF COOROW MR TED JACK 63-73, 86-87 WA DEPARTMENT OF REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT MR KEVIN LEE 73-76 ISOLATED CHILDREN’S PARENTS’ ASSOCIATION WA MS ELYCE DONAGHY 76-78 WHEATBELT BUSINESS NETWORK MS AMANDA WALKER 79-86 TELSTRA MR BOYD BROWN 89 SHIRE OF WESTONIA MR JAMIE CRIDDLE 89-90104-106 Telecommunications 14/02/17 2 © C’wlth of Australia MR LINDWALL: Good morning. Welcome to the public hearings for the Productivity Commission inquiry into the Telecommunications Universal Service Obligation. My name is Paul Lindwall and I am the Commissioner for the inquiry. I would like to start off with a few housekeeping matters. In the event of an emergency, Travelodge Hotel staff will direct or assist people in evacuating and moving to the Assembly points. We will be breaking for morning tea at around 11 am. We look like we will be concluding the hearing around 1 pm. If you have any particular questions, or wish to present at this hearing, please see PaoYi here at the back, who can arrange you to present or make a statement. -

Optus SMS Toolkit

Optus SMS Toolkit Integrate SMS Messaging into your existing software with SMS Toolkit. Email and SMS are two of the most powerful and popular communication tools in business today. Optus now gives your business the ability to enhance your applications by integrating SMS messaging into your existing software with SMS Toolkit. Developers and web designers can use the SMS Toolkit API to integrate SMS and messaging functionality into existing software. Enhance web sites, intranets or applications to send SMS/MMS* messages to and from over 130 countries. Build webs sites and applications that send reminders, alerts, leads and can deliver mobile content. Enhance your CRM solution with 2-way SMS messaging, MMS and Wap push. The SMS Toolkit provides all the tools required to build state-of-the-art mobile Internet, SMS or MMS solutions. FEATURES AND BENEFITS I SOAP/XML Web-Service API - a standard and popular programming interface. I Increases productivity by allowing businesses to automate existing systems with SMS functionality. I Provides easy to use interfaces for Microsoft and Unix/Linux as well as an extensive set of example source codes and documentation for VB.NET, C++ and PHP allowing you to reduce development time. I Code design using the latest development technology meaning reduced development costs. I Integration with existing software allows you to create your own value added services for customers and staff. I Royalty free with 4 hours of telephone support included. CUSTOMISATION AT YOUR FINGERTIPS SMS Toolkit is ideal for organisations looking to develop custom solutions or enhance existing software wIth SMS messaging functionality, without the need for additional customer-premise hardware. -

Optus Sustainability Report 2020 Our Highlights Contents

Optus Sustainability Report 2020 Our Highlights Contents 3 Our Company Strategy and Purpose 4 About Optus 5 About this Report 6 A Message from our Chairman and Chief Executive Officer 8 Supporting Resilience 13 The Most Connected Communities 27 Our Greatest Asset 38 The Best Experience 46 The Smallest Footprint 57 Addressing the Sustainable Development Goals 2 OVERVIEW THE MOST CONNECTED COMMUNITIES OUR GREATEST ASSET THE BEST EXPERIENCE THE SMALLEST FOOTPRINT ADDRESSING THE SDGS BCK FWD HOME Our Company Strategy and Purpose Engaging Digital Inclusion & our People Citizenship Wellbeing Climate At Optus we’re passionate about powering optimism Change & Education & Carbon Employment with options. We believe that nothing drives greater optimism than a company that operates sustainably to create lasting positive impact for its stakeholders and meet the present and future needs of society. Product Stewardship As a telecommunications company we believe we have a distinct and unique role to play in creating tomorrow’s world. Sustainability Our purpose helps us to think about the world we want Framework and embeds an ethos of innovation into our work. Our The Highest sustainability strategy is based on how we can harness Quality Service & Products our purpose and use our skills, resources and expertise to contribute to a better future for our customers, our people, the environment and our community. We focus The Best Ethical & on areas outlined in our sustainability framework where Talent Responsible we believe we can make a significant impact. Practices A Diverse & Health & Inclusive Safety Always Workship #1 Framework 3 OVERVIEW THE MOST CONNECTED COMMUNITIES OUR GREATEST ASSET THE BEST EXPERIENCE THE SMALLEST FOOTPRINT ADDRESSING THE SDGS BCK FWD HOME About Optus Optus is the second largest provider of telecommunications services in Australia in terms of revenue and employs more than 7,000 people nationally, who together are a reflection of our multicultural country and diverse customer base. -

Annual Report 2011

Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman TELECOMMUNICATIONS INDUSTRY OMBUDSMAN 2011 ANNUAL REPORT A year of change CONTENTS ABOUT US 1 How the TIO works 1 Board and Council 2 THE YEAR AT A GLANCE 5 Ombudsman’s overview 5 A year of change 6 Highlights 7 Top trends 2010-11 8 PERFORMANCE 11 Resolving complaints 11 Our organisation 18 Contributing to the co-regulatory environment 22 Creating awareness 23 The Road Ahead 26 TIO IN NUMBERS 27 Complaint statistics 2010–11 27 Top 10 members 32 Complaints by member 37 Timeliness 49 Industry Codes 50 FiNANCiaL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE 2011 55 Financial report 56 APPENDICES 88 Appendix 1 Systemic issues 1 July 2010- 30 June 2011 88 Appendix 2 List of public submissions made by the TIO 91 Appendix 3 Calendar of outreach activities 93 Appendix 4 Issues by Category 94 Appendix 5 Explanation of TIO data terms 108 1 ABOUT US How the TIO works The Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman is a fast, free and fair dispute resolution service for small business and residential consumers who have a complaint about their telephone or internet service in Australia. We are independent and do not take sides. Our goal is to settle disputes quickly in an objective and non-bureaucratic way. We are able to investigate complaints about telephone and internet services, including by collecting all documentation and information relevant to the complaint. We have the authority to make binding decisions (decisions a telecommunications company is legally obliged to implement) up to the value of $30,000, and recommendations up to the value of $85,000. -

Exesim Ultra 3G Mobile Voice Plan (4G17-ULTRA)

CRITICAL INFORMATION SUMMARY ExeSim Ultra 3G Mobile Voice Plan (4G17-ULTRA) This summary gives you the important information you need to know about your Exetel mobile Voice plan. It covers things like the length of your contract, billing, what’s covered and what’s not. Information About The Service This plan offers a $79.99 3G mobile voice service on a month to The monthly allowances are not interchangeable and unused value month term which includes one included value allowance and two from one allowance cannot be transferred to another or into the unlimited allowances: current of following month if unused. 1. UNLIMITED National talk to Landlines and Mobiles Subject to the Exetel Mobile Acceptable use Policy and the Exetel Terms and Conditions go to: 2. UNLIMITED National SMS and MMS http://www.exetel.com.au/terms 3. 90GB of 3G National Data* Information about pricing Recurring charges are payable monthly in advance. The allowances expire at the end of each month. The included National Data Minimum monthly cost allowance includes all usage for both uploads and downloads. This is a stand-alone service and is not bundled with any other product. $79.99 is the minimum financial commitment for this offer. If your * Prorata allowance applies in the first month. usage exceeds the included National 3G Data Allowance, additional usage charges will apply. BYO device The most common charges used to calculate your usage A compatible mobile (with the Optus 3G Network) device is (allowance and any excess) are as follows; required to gain access to the service, and is required to be operated inside the coverage area. -

Optus Internet Everyday

Critical information summary This summary does not reflect any special discounts, bonus data or promotions which may apply from time to time. Optus Internet Everyday Plan ID: 35287684 Information about the Service Description of the Service This plan is for a stand-alone Fixed Broadband service that is supplied using the Optus nbn™ network. The Optus Internet Everyday plan also has the option of bundling a Fixed Telephone service. See “Optional Phone Plans” (page 3) section for more information. Plan Minimum monthly charge $79/mth Minimum term Month-to-month Monthly data allowance Unlimited Start-up fee $0 However, fees may apply for a first time nbn connection to dwellings in new developments, for additional lines or for non-standard installations Modem charges $252 Optus will cover the cost of the modem if you remain connected for 36 months (i.e. $7/mth over 36 months) Cancellation fee There is no cancellation fee for this plan. If applicable, you’ll need to pay out any remaining device payments in full (any credits or discounts will be forfeited), plus, all charges incurred up to the end of the billing cycle in which your service is cancelled (unless otherwise specified) Minimum total cost $331 (includes $252 modem cost and one month of plan fee) (when you pay by direct debit) Service and plan availability Device Payment Plans Optus Broadband services are not available in all areas or to You can buy an eligible device (such as a Booster) on a Device all premises. The broadband service offered will be determined Payment Plan (DPP) and pay for it over a selected term by by what is available at your location. -

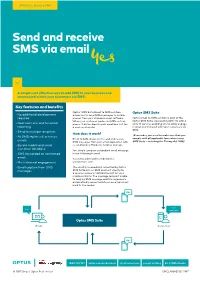

Send and Receive SMS Via Email

SMS Suite: Email to SMS Send and receive SMS via email . A simple cost effective way to add SMS to your business and communicate with your customers via SMS. Key features and benefits Optus’ SMS Suite Email to SMS solution Optus SMS Suite • No additional development allows you to send SMS messages to mobile required phones from your standard email software. Optus Email to SMS solution is part of the When your customer replies via SMS on their Optus SMS Suite, a powerful platform with a • Near real time and historical phone, it arrives back in your email box just like suite of services enabling you to easily engage, reporting a new email would. market and transact with your customers via SMS. • Send to multiple recipients How does it work? (Remember, you need to make sure that you • All SMS replies will arrive as comply with all applicable laws when using emails Email to SMS allows you to send and receive SMS messages from your email application with SMS Suite – including the Privacy Act 1988) • Build a mobile and email no additional software to install or manage. customer database You simply compose a standard email message • SMS forwardedSecurity to nominated Opinion Paper in the following format email +countrycodemobilenumber@sms. • Multi-channel engagement yourdomain.com. • Email capture from SMS The email is received and converted by Optus messages SMS Suite into an SMS and sent directly to a mobile number or distribution list for your mobile contacts. The message recipient is able to reply by SMS message and this response is automatically converted into an email and sent back to the sender. -

1. Optus - Background, Networks and Services

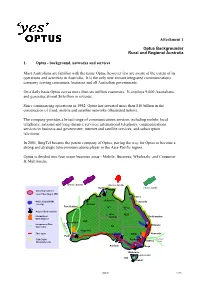

Attachment 1 Optus Backgrounder Rural and Regional Australia 1. Optus - background, networks and services Most Australians are familiar with the name Optus, however few are aware of the extent of its operations and activities in Australia. It is the only new entrant integrated communications company serving consumers, business and all Australian governments. On a daily basis Optus serves more than six million customers. It employs 9,000 Australians, and generates almost $6 billion in revenue. Since commencing operations in 1992, Optus has invested more than $10 billion in the construction of fixed, mobile and satellite networks (illustrated below). The company provides a broad range of communications services including mobile; local telephony; national and long distance services; international telephony; communications services to business and government; internet and satellite services; and subscription television. In 2001, SingTel became the parent company of Optus, paving the way for Optus to become a strong and strategic telecommunications player in the Asia-Pacific region. Optus is divided into four major business areas - Mobile; Business; Wholesale; and Consumer & Multimedia. B-Series Satellite A-Series Satellite Darwin C-Series Satellite Switching Systems/ Local Fibre Ring in CBD Cairns Mobile Digital(GSM) Katherine Townsville coverage Broome Port Hedland NT Mt Isa National Earth Stations Alice QLD International Springs Rockhampton Earth Station s WA S Geraldton International Fibre e M Brisbane e SA Optic Cable W e 3 Kalgoorlie Fibre Optic Port Augusta NSW Newcastle Perth SDH Digital Canberra Southern Sydney Microwave Link Cross VIC Adelaide Bega Melbourne Launceston TAS Hobart Optus 1 of 5 The company’s Mobile business unit has captured around one-third of the total Australian GSM mobile market and leads the market in mobile data take up.