Pauline Boty by Caroline Coon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First-Ever Exhibition of British Pop Art in London

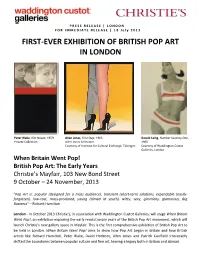

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE | 1 8 J u l y 2 0 1 3 FIRST- EVER EXHIBITION OF BRITISH POP ART IN LONDON Peter Blake, Kim Novak, 1959 Allen Jones, First Step, 1966 Gerald Laing, Number Seventy-One, Private Collection Allen Jones Collection 1965 Courtesy of Institute for Cultural Exchange, Tübingen Courtesy of Waddington Custot Galleries, London When Britain Went Pop! British Pop Art: The Early Years Christie’s Mayfair, 103 New Bond Street 9 October – 24 November, 2013 "Pop Art is: popular (designed for a mass audience), transient (short-term solution), expendable (easily- forgotten), low-cost, mass-produced, young (aimed at youth), witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, Big Business" – Richard Hamilton London - In October 2013 Christie’s, in association with Waddington Custot Galleries, will stage When Britain Went Pop!, an exhibition exploring the early revolutionary years of the British Pop Art movement, which will launch Christie's new gallery space in Mayfair. This is the first comprehensive exhibition of British Pop Art to be held in London. When Britain Went Pop! aims to show how Pop Art began in Britain and how British artists like Richard Hamilton, Peter Blake, David Hockney, Allen Jones and Patrick Caulfield irrevocably shifted the boundaries between popular culture and fine art, leaving a legacy both in Britain and abroad. British Pop Art was last explored in depth in the UK in 1991 as part of the Royal Academy’s survey exhibition of International Pop Art. This exhibition seeks to bring a fresh engagement with an influential movement long celebrated by collectors and museums alike, but many of whose artists have been overlooked in recent years. -

R.B. Kitaj Papers, 1950-2007 (Bulk 1965-2006)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3q2nf0wf No online items Finding Aid for the R.B. Kitaj papers, 1950-2007 (bulk 1965-2006) Processed by Tim Holland, 2006; Norma Williamson, 2011; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the R.B. Kitaj 1741 1 papers, 1950-2007 (bulk 1965-2006) Descriptive Summary Title: R.B. Kitaj papers Date (inclusive): 1950-2007 (bulk 1965-2006) Collection number: 1741 Creator: Kitaj, R.B. Extent: 160 boxes (80 linear ft.)85 oversized boxes Abstract: R.B. Kitaj was an influential and controversial American artist who lived in London for much of his life. He is the creator of many major works including; The Ohio Gang (1964), The Autumn of Central Paris (after Walter Benjamin) 1972-3; If Not, Not (1975-76) and Cecil Court, London W.C.2. (The Refugees) (1983-4). Throughout his artistic career, Kitaj drew inspiration from history, literature and his personal life. His circle of friends included philosophers, writers, poets, filmmakers, and other artists, many of whom he painted. Kitaj also received a number of honorary doctorates and awards including the Golden Lion for Painting at the XLVI Venice Biennale (1995). He was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1982) and the Royal Academy of Arts (1985). -

Frank Bowling Cv

FRANK BOWLING CV Born 1934, Bartica, Essequibo, British Guiana Lives and works in London, UK EDUCATION 1959-1962 Royal College of Art, London, UK 1960 (Autumn term) Slade School of Fine Art, London, UK 1958-1959 (1 term) City and Guilds, London, UK 1957 (1-2 terms) Regent Street Polytechnic, Chelsea School of Art, London, UK SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1962 Image in Revolt, Grabowski Gallery, London, UK 1963 Frank Bowling, Grabowski Gallery, London, UK 1966 Frank Bowling, Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1971 Frank Bowling, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, New York, USA 1973 Frank Bowling Paintings, Noah Goldowsky Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1973-1974 Frank Bowling, Center for Inter-American Relations, New York, New York, USA 1974 Frank Bowling Paintings, Noah Goldowsky Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1975 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, William Darby, London, UK 1976 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Watson/de Nagy and Co, Houston, Texas, USA 1977 Frank Bowling: Selected Paintings 1967-77, Acme Gallery, London, UK Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, William Darby, London, UK 1979 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1980 Frank Bowling, New Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1981 Frank Bowling Shilderijn, Vecu, Antwerp, Belgium 1982 Frank Bowling: Current Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, -

Derek Boshier: Rethink/Re-Entry Online

mM5uc (Ebook pdf) Derek Boshier: Rethink/Re-entry Online [mM5uc.ebook] Derek Boshier: Rethink/Re-entry Pdf Free From Thames Hudson audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1211293 in Books 2015-11-09Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 11.60 x 1.20 x 9.50l, .0 #File Name: 0500093881288 pages | File size: 26.Mb From Thames Hudson : Derek Boshier: Rethink/Re-entry before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Derek Boshier: Rethink/Re-entry: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Five StarsBy DTSExcellent comprehensive monograph on the eclectic work of a significant, but overlooked contemporary artist.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Five StarsBy M S BI love everything about this collection of great art. A notable monograph on British artist Derek Boshier, covering his extensive collection of work from the mid-1950s to the present day Derek Boshierrsquo;s art has journeyed through a number of different phases, from films and painting to album covers, photography, and book making. He was a contemporary of Pauline Boty, Peter Blake, and David Hockney at the Royal College of Art and first achieved fame as part of the British Pop Art generation of the early 1960s. He then progressed to making wholly abstract illusionistic paintings with brash colors and strong patterns in shapes that broke playfully free of conventional rectangular formats. At the beginning of the 1970s, Boshier gave up painting for more than a decade and turned to book making, drawing, collage, printmaking, photography, posters, and filmmaking. -

Inperson Innewyork Email Newsletter

Sign In Register You are subscribed to the Dart: Design Arts Daily inPerson inNewYork email newsletter. By Peggy Roalf Wednesday March 31, 2021 Like Share You and 2.3K others like this. Search: Most Recent: Pictoplasma #1FaceValue Daniel Bejar at Socrates Sculpture Park inPerson inNewYork Art and Design in New York The DART Board: 03.18.2021 Mark Jason Page's Workspace Archives: Friday, April 2, 6-8 pm: Owen James Gallery April 2021 March 2021 David Sandlin | Belfaust: Paintings, screenprints, books February 2021 January 2021 The artist will be in attendance at the gallery Saturday April 3rd (from 2-5 PM) to meet with visitors and December 2020 discuss his work. The following is a preview. Above: David Sandlin, Belfast Bus, acrylic on canvas. November 2020 October 2020 From the late 1960s until 1998, Northern Ireland suffered through The Troubles: an era of severe political and September 2020 sectarian violence, which was particularly brutal in the cities of Derry and Belfast. It emerged from a tormented August 2020 national history as a call for more civil rights by the area’s Catholic minority. At its heart was, and is, a bitter July 2020 debate over whether Northern Ireland should remain part of the United Kingdom or rejoin Ireland as a united June 2020 republic. Born in the late 1950s, artist David Sandlin grew up in Belfast during the 1960s and 70s, as the violence May 2020 drastically increased. Sandlin’s family was Protestant, but siblings had married into Catholic families. Due to continued threats Sandlin’s family moved to rural Alabama in the United States. -

Intertextuality and the Plea for Plurality in Ali Smith's Autumn

Smithers 1 Intertextuality and the Plea for Plurality in Ali Smith’s Autumn BA Thesis English Language and Culture Annick Smithers 6268218 Supervisor: Simon Cook Second reader: Cathelein Aaftink 26 June 2020 4911 words Smithers 2 Abstract This thesis analyses the way in which intertextuality plays a role in Ali Smith’s Autumn. A discussion of the reception and some readings of the novel show that not much attention has been paid yet to intertextuality in Autumn, or in Smith’s other novels, for that matter. By discussing different theories of the term and highlighting the influence of Bakhtin’s dialogism on intertextuality, this thesis shows that both concepts support an important theme present in Autumn: an awareness and acceptance of different perspectives and voices. Through a close reading, this thesis analyses how this idea is presented in the novel. It argues that Autumn advocates an open-mindedness and shows that, in the novel, this is achieved through a dialogue. This can mainly be seen in scenes where the main characters Elisabeth and Daniel are discussing stories. The novel also shows the reverse of this liberalism: when marginalised voices are silenced. Subsequently, as the story illustrates the state of the UK just before and after the 2016 EU referendum, Autumn demonstrates that the need for a dialogue is more urgent than ever. Smithers 3 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 “A Brexit Novel” ...................................................................................................................... -

Nepantla Press Release

Garth Greenan Gallery 545 West 20th Street New York New York 10011 212 929 1351 www.garthgreenan.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Garth Greenan (212) 929-1351 [email protected] www.garthgreenan.com Derek Boshier: Alchemy Alchemy Possibilities of Nature, 2020, acrylic on canvas, 66 x 96 inches Garth Greenan Gallery is pleased to announce Derek Boshier: Alchemy Alchemy, an exhibition of paintings and works on paper by Derek Boshier, all made in 2020. Since his landmark early paintings that helped establish the British Pop Art scene in the 1960s, Boshier has continued to combine popular imagery into visually stunning and intellectually confounding works. Opening Thursday, March 25, 2021, the exhibition is the artist’s first at the gallery. The exhibition includes several of the artist’s paintings, each containing Boshier’s careful clustering of logically contradictory but psychically resonant elements. “I collect images,” says Boshier, “and like to use them randomly.” In spite of the inevitable meanings they produce, Boshier’s juxtapositions are often the products of serendipity. The images, thoughts, and events that present themselves over the course of a day, or in the sequential pages of a magazine, are often non-sequiturs, yet occasionally create lasting and meaningful psychic impact. In his sprawling painting Afghanistan (Christmas Day) (2020), Boshier relates the experience of handling Christmas wrapping paper while watching news of war in snowy Afghanistan. The jarring combination of smiling snowmen next to coils of barbed wire, blood, and bodies again suggests a cascade of meanings: about the extremes of human possibility in peaceful celebration and war, or about the links between our civilization’s polite opulence and its aggressive military adventures. -

Derek Boshier Reviewed in Hyperallergic

An Artist’s Lifetime of Asking the Hard Questions Derek Boshier’s commitment to being a witness to the catastrophes and jarring discrepancies of daily living has contributed to his near-invisibility in New York. BY JOHN YAU APRIL 9, 2021 “Some Landscapes” (2020), acrylic on canvas, 72 x 60 inches Derek Boshier has followed an unconventional career path ever since he received his MFA from the Royal College of Art in 1962, where his classmates included Allen Jones (until he was expelled), Pauline Boty, R. B. Kitaj, Peter Phillips, and David Hockney, with whom he has maintained a long and continuous friendship. Like many of his classmates, Boshier is widely considered a central member of the first generation of English Pop artists. He was one of four artists featured in the film Pop Goes the Easel (1962), directed by Ken Russell and broadcast on the BBC (March 25, 1962). (The others were Peter Blake, Boty, and Phillips.) But while his peers in this group followed a trajectory that seemed laid out for them, he went to India for a year. After returning to England, he painted Pop abstractions that shared some qualities with the American artist Nicholas Krushenick, also an outlier. Starting in 1967, feeling that painting was not equipped to deal with everyday life — which, at that time, was characterized by convulsive change and unrelenting upheaval — Boshier concentrated on photography, film, video, assemblage, and installations. He did not paint again until 1980, when he moved Houston, Texas, and began teaching at the University of Houston. Two of the first paintings he did in 1980 were portraits of Malcolm Morley and of David Bowie in the play The Elephant Man. -

New Statesman Bowling May 30, 2019

NewStatesman Surface tensions A painter who once shone as part of British art's golden generationis back in the limelight again By Michael Prodger In the years around 1910, the Slade School FrankBowling ofa picture and the way they are used engage of Art had what one of its tutors Henry the emotions. It is such concerns - "paint's Tonks called "a crisis of brilliance", when Tate Britain, London SW1 possibilities", in his words - rather than its intake included an extraordinary clus social comment that he believes should be ter of artists who would go on to paint the if Britain saw him as an outsider he would at the core of a black aesthetic in art. defining images of the First World War become one, and leftfor New York. I twas to There are hints of his own urge to ex - the likes of Paul Nash, CRW Nevinson, be a decade beforehe lived in London again, periment in the key painting of his London Mark Gertler and Stanley Spencer. In 1959, although formany years now he has divided years, Mirror ofi964-66. A colour-rich ver it was the Royal College of Art's tum: his working life between the two cities. tical image, it offers a selection of the styles among its students were several figures who This jumbled artisticidentity is part of the available to the young artist at that moment would help define the look of the 1960s, reason Bowling, now 85, has remained so in time. At the centreis the spiral staircase among them David Hockney, RB Kitaj, much less well known than his RCA pee-rs, of the RCA and Bowling himself features Derek Boshier and Allen Jones (although something the retrospective staged by Tate twice - at the top and bottom- with his then Hockney remembers the staff thinking Britain seeks to put right. -

Allen Jones RA Burlington Gardens 13 November 2014 – 25 January 2015

Allen Jones RA Burlington Gardens 13 November 2014 – 25 January 2015 Lead series supporter: This autumn the Royal Academy of Arts will present the first major exhibition of Allen Jones’ work in the UK since 1995. As one of the UK’s most influential and celebrated living artists, this will be a long-overdue appraisal of Jones’ comprehensive contribution to British Pop art. Allen Jones RA will span the artist’s entire career from the 1960s to the present. Comprising over 80 works, the exhibition will feature examples of Jones’ paintings and sculpture, including the iconic furniture works from the late 60s, and new works created especially for this exhibition. Rarely-seen drawings will also be displayed to showcase Jones’ exceptional skills as a draughtsman, and the important influence of the medium of drawing on his practice as a whole. Moving away from a traditional chronological approach, the works will be grouped into key sequences, to allow connections and common themes to emerge and to promote a comprehensive understanding of Jones’ wide-ranging artistic practice. Allen Jones is a key figure in British Pop art whose reputation was established in the 1960s at the Royal College of Art, London, where he studied alongside celebrated artists David Hockney RA, Derek Boshier, Peter Phillips RA and Ron Kitaj amongst others. This cohort of students was catapulted into the spotlight of the British art scene with a new visual language, firmly rooted in contemporary culture, and with the human figure often central to their work. The female figure has remained an enduring interest for Jones, who has continually found fascination in popular culture’s prolific and differing depictions of femininity, ranging from the erotic to the seductive and the glamorous. -

000000560.Sbu.Pdf (493.3Kb)

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... R. B. Kitaj’s Paintings In Terms of Walter Benjamin’s Allegory Theory A Thesis Presented by Bo-Kyung Choi to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University May 2009 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Bo-Kyung Choi We, the thesis committee for the above candidate for the Master of Arts degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this thesis. Donald Kuspit – Thesis Advisor Distinguished Professor of Art History department Andrew Uroskie – Chairperson of Defense Assistant Professor of Art History department This thesis is accepted by the Graduate School Lawrence Martin Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Thesis R. B. Kitaj’s Paintings In Terms of Walter Benjamin’s Allegory Theory by Bo-Kyung Choi Master of Arts in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University 2009 This thesis investigates R.B. Kitaj’s later paintings since the 1980s, focusing on his enthusiasm for fragments. While exploring diverse media from print to painting throughout his work, his main interest was the use of fragments, which in turn revealed his broader interests in the notion of historicity as fragments detached from its original context. Such notion based on Walter Benjamin’s theory of allegory allowed him to embrace a much more comprehensive theme of Jewishness as the subject of his painting. -

Winter 2020 Contents

Yale Yale Autumn & Winter 2020 Autumn & Yale AUTUMN & WINTER 2020 Contents General Interest Highlights | Hardback 1–21 General Interest Highlights | Paperback 22–28 Art 2, 4, 26, 29–60, 67 fashion & textile 30, 34, 53 architecture 32, 47, 48, 50, 59 design & decorative 29, 31, 33, 35, 48–51, 58, 59 modern & contemporary 37, 40–42, 45, 46, 51–54, 59, 60 18th & 19th century 36, 37, 43, 54, 56 15th, 16 th & 17th century 40, 44, 45, 54, 56, 57 ancient & antiquity 48, 49, 57–59 collections & theory 44, 46, 58, 59, 60 Mathematics, Science & Medicine 21, 22, 63, 72 Business & Economics 7, 11, 12, 61 History 1, 2, 4, 6, 9, 14, 15, 20–28, 62–64, 74–76 Biography & Memoir 2, 4, 5, 9, 16, 17, 23, 26, 47, 65, 75 Philosophy, Theology & Jewish Studies 9, 13, 65–68 Film, Performing Arts, Literary Studies 8, 13, 16, 17, 24–27, 52, 65, 69–71 International Affairs & Political Science 3, 10, 18, 19, 28, 61, 62, 64 American Studies 28, 74–76 Psychology, Social & Environmental Science 16, 22, 60, 62, 63, 73, 76 Picture Credits & Index 77–79 Sales Contacts 80 Ordering Information 81 Rights, Inspection Copy, Review Copy Information 81 Yale University Press YaleBooks 47 Bedford Square @yalebooks London WC1B 3DP tel 020 7079 4900 yalebooksblog.co.uk general email [email protected] www.yalebooks.co.uk A thrilling history of MI9 – the WWII organisation that engineered the escape of Allied forces from behind enemy lines MI9 A History of The Secret Service for Escape and Evasion in World War Two Helen Fry Helen Fry is a specialist in the When Allied fighters were trapped behind enemy lines, one branch of history of British Intelligence.