Chris, Steve, and Yinka: We Run Tings 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First-Ever Exhibition of British Pop Art in London

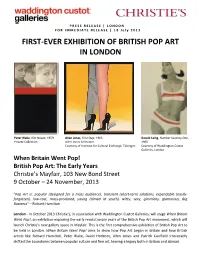

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE | 1 8 J u l y 2 0 1 3 FIRST- EVER EXHIBITION OF BRITISH POP ART IN LONDON Peter Blake, Kim Novak, 1959 Allen Jones, First Step, 1966 Gerald Laing, Number Seventy-One, Private Collection Allen Jones Collection 1965 Courtesy of Institute for Cultural Exchange, Tübingen Courtesy of Waddington Custot Galleries, London When Britain Went Pop! British Pop Art: The Early Years Christie’s Mayfair, 103 New Bond Street 9 October – 24 November, 2013 "Pop Art is: popular (designed for a mass audience), transient (short-term solution), expendable (easily- forgotten), low-cost, mass-produced, young (aimed at youth), witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, Big Business" – Richard Hamilton London - In October 2013 Christie’s, in association with Waddington Custot Galleries, will stage When Britain Went Pop!, an exhibition exploring the early revolutionary years of the British Pop Art movement, which will launch Christie's new gallery space in Mayfair. This is the first comprehensive exhibition of British Pop Art to be held in London. When Britain Went Pop! aims to show how Pop Art began in Britain and how British artists like Richard Hamilton, Peter Blake, David Hockney, Allen Jones and Patrick Caulfield irrevocably shifted the boundaries between popular culture and fine art, leaving a legacy both in Britain and abroad. British Pop Art was last explored in depth in the UK in 1991 as part of the Royal Academy’s survey exhibition of International Pop Art. This exhibition seeks to bring a fresh engagement with an influential movement long celebrated by collectors and museums alike, but many of whose artists have been overlooked in recent years. -

Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art Library: New Accessions March 2017

Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art Library: New accessions March 2017 0730807886 Art Gallery Board of Claude Lorrain : Caprice with ruins of the Roman forum Adelaide: Art Gallery Board of South Australia, C1986 (44)7 CLAU South Australia (PAMPHLET) 8836633846 Schmidt, Arnika Nino Costa, 1826-1903 : transnational exchange in Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2016 (450)7 COST(N).S European landscape painting 0854882502 Whitechapel Art William Kentridge : thick time London: Whitechapel Gallery, 2016 (63)7 KENT(W).B Gallery 0956276377 Carey, Louise Art researchers' guide to Cardiff & South Wales [London]: ARLIS UK & Ireland, 2015 026 ART D12598 Petti, Bernadette English rose : feminine beauty from Van Dyck to Sargent [Barnard Castle]: Bowes Museum, [2016] 062 BAN-BOW 0903679108 Holburne Museum of Modern British pictures from the Target collection Bath: Holburne Museum of Art, 2005 062 BAT-HOL Art D10085 Kettle's Yard Gallery Artists at war, 1914-1918 : paintings and drawings by Cambridge: Kettle's Yard Gallery, 1974 062 CAM-KET Muirhead Bone, James McBey, Francis Dodd, William Orpen, Eric Kennington, Paul Nash and C R W Nevinson D10274 Herbert Read Gallery, Surrealism in England : 1936 and after : an exhibition to Canterbury: Herbert Read Gallery, Canterbury College of Art, 1986 062 CAN-HER Canterbury College of celebrate the 50th anniversary of the First International Art Surrealist Exhibition in London in June 1936 : catalogue D12434 Crawford Art Gallery The language of dreams : dreams and the unconscious in Cork: Crawford Art Gallery, -

Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU 18th Annual Africana Studies Student Research Africana Studies Student Research Conference Conference and Luncheon Feb 12th, 1:30 PM - 2:45 PM Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art Shelby Miller Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons Miller, Shelby, "Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art" (2017). Africana Studies Student Research Conference. 1. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf/2016/004/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Events at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies Student Research Conference by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Shelby Miller Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art Bibliographic Style: MLA 1 How does one define the concepts of space and place and further translate those theories to the Caribbean region? Through abstract modes of representation, artists from these islands can shed light on these concepts in their work. Involute theories can be discussed in order to illuminate the larger Caribbean space and all of its components in abstract art. The trialectics of space theory deals with three important factors that include the physical, cognitive, and experienced space. All three of these aspects can be displayed in abstract artwork from this region. By analyzing this theory, one can understand why Caribbean artists reverted to the abstract style—as a means of resisting the cultural establishments of the West. To begin, it is important to differentiate the concepts of space and place from the other. -

R.B. Kitaj Papers, 1950-2007 (Bulk 1965-2006)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3q2nf0wf No online items Finding Aid for the R.B. Kitaj papers, 1950-2007 (bulk 1965-2006) Processed by Tim Holland, 2006; Norma Williamson, 2011; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the R.B. Kitaj 1741 1 papers, 1950-2007 (bulk 1965-2006) Descriptive Summary Title: R.B. Kitaj papers Date (inclusive): 1950-2007 (bulk 1965-2006) Collection number: 1741 Creator: Kitaj, R.B. Extent: 160 boxes (80 linear ft.)85 oversized boxes Abstract: R.B. Kitaj was an influential and controversial American artist who lived in London for much of his life. He is the creator of many major works including; The Ohio Gang (1964), The Autumn of Central Paris (after Walter Benjamin) 1972-3; If Not, Not (1975-76) and Cecil Court, London W.C.2. (The Refugees) (1983-4). Throughout his artistic career, Kitaj drew inspiration from history, literature and his personal life. His circle of friends included philosophers, writers, poets, filmmakers, and other artists, many of whom he painted. Kitaj also received a number of honorary doctorates and awards including the Golden Lion for Painting at the XLVI Venice Biennale (1995). He was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1982) and the Royal Academy of Arts (1985). -

Frank Bowling Cv

FRANK BOWLING CV Born 1934, Bartica, Essequibo, British Guiana Lives and works in London, UK EDUCATION 1959-1962 Royal College of Art, London, UK 1960 (Autumn term) Slade School of Fine Art, London, UK 1958-1959 (1 term) City and Guilds, London, UK 1957 (1-2 terms) Regent Street Polytechnic, Chelsea School of Art, London, UK SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1962 Image in Revolt, Grabowski Gallery, London, UK 1963 Frank Bowling, Grabowski Gallery, London, UK 1966 Frank Bowling, Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1971 Frank Bowling, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, New York, USA 1973 Frank Bowling Paintings, Noah Goldowsky Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1973-1974 Frank Bowling, Center for Inter-American Relations, New York, New York, USA 1974 Frank Bowling Paintings, Noah Goldowsky Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1975 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, William Darby, London, UK 1976 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Watson/de Nagy and Co, Houston, Texas, USA 1977 Frank Bowling: Selected Paintings 1967-77, Acme Gallery, London, UK Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, William Darby, London, UK 1979 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1980 Frank Bowling, New Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1981 Frank Bowling Shilderijn, Vecu, Antwerp, Belgium 1982 Frank Bowling: Current Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, -

Derek Boshier: Rethink/Re-Entry Online

mM5uc (Ebook pdf) Derek Boshier: Rethink/Re-entry Online [mM5uc.ebook] Derek Boshier: Rethink/Re-entry Pdf Free From Thames Hudson audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1211293 in Books 2015-11-09Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 11.60 x 1.20 x 9.50l, .0 #File Name: 0500093881288 pages | File size: 26.Mb From Thames Hudson : Derek Boshier: Rethink/Re-entry before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Derek Boshier: Rethink/Re-entry: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Five StarsBy DTSExcellent comprehensive monograph on the eclectic work of a significant, but overlooked contemporary artist.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Five StarsBy M S BI love everything about this collection of great art. A notable monograph on British artist Derek Boshier, covering his extensive collection of work from the mid-1950s to the present day Derek Boshierrsquo;s art has journeyed through a number of different phases, from films and painting to album covers, photography, and book making. He was a contemporary of Pauline Boty, Peter Blake, and David Hockney at the Royal College of Art and first achieved fame as part of the British Pop Art generation of the early 1960s. He then progressed to making wholly abstract illusionistic paintings with brash colors and strong patterns in shapes that broke playfully free of conventional rectangular formats. At the beginning of the 1970s, Boshier gave up painting for more than a decade and turned to book making, drawing, collage, printmaking, photography, posters, and filmmaking. -

Inperson Innewyork Email Newsletter

Sign In Register You are subscribed to the Dart: Design Arts Daily inPerson inNewYork email newsletter. By Peggy Roalf Wednesday March 31, 2021 Like Share You and 2.3K others like this. Search: Most Recent: Pictoplasma #1FaceValue Daniel Bejar at Socrates Sculpture Park inPerson inNewYork Art and Design in New York The DART Board: 03.18.2021 Mark Jason Page's Workspace Archives: Friday, April 2, 6-8 pm: Owen James Gallery April 2021 March 2021 David Sandlin | Belfaust: Paintings, screenprints, books February 2021 January 2021 The artist will be in attendance at the gallery Saturday April 3rd (from 2-5 PM) to meet with visitors and December 2020 discuss his work. The following is a preview. Above: David Sandlin, Belfast Bus, acrylic on canvas. November 2020 October 2020 From the late 1960s until 1998, Northern Ireland suffered through The Troubles: an era of severe political and September 2020 sectarian violence, which was particularly brutal in the cities of Derry and Belfast. It emerged from a tormented August 2020 national history as a call for more civil rights by the area’s Catholic minority. At its heart was, and is, a bitter July 2020 debate over whether Northern Ireland should remain part of the United Kingdom or rejoin Ireland as a united June 2020 republic. Born in the late 1950s, artist David Sandlin grew up in Belfast during the 1960s and 70s, as the violence May 2020 drastically increased. Sandlin’s family was Protestant, but siblings had married into Catholic families. Due to continued threats Sandlin’s family moved to rural Alabama in the United States. -

Generation Painting: Abstraction and British Art, 1955–65 Saturday 5 March 2016, 09:45-17:00 Howard Lecture Theatre, Downing College, Cambridge

Generation Painting: Abstraction and British Art, 1955–65 Saturday 5 March 2016, 09:45-17:00 Howard Lecture Theatre, Downing College, Cambridge 09:15-09:40 Registration and coffee 09:45 Welcome 10:00-11:20 Session 1 – Chaired by Dr Alyce Mahon (Trinity College, Cambridge) Crossing the Border and Closing the Gap: Abstraction and Pop Prof Martin Hammer (University of Kent) Fellow Persians: Bridget Riley and Ad Reinhardt Moran Sheleg (University College London) Tailspin: Smith’s Specific Objects Dr Jo Applin (University of York) 11:20-11:40 Coffee 11:40-13:00 Session 2 – Chaired by Dr Jennifer Powell (Kettle’s Yard) Abstraction between America and the Borders: William Johnstone’s Landscape Painting Dr Beth Williamson (Independent) The Valid Image: Frank Avray Wilson and the Biennial Salon of Commonwealth Abstract Art Dr Simon Pierse (Aberystwyth University) “Unity in Diversity”: New Vision Centre and the Commonwealth Maryam Ohadi-Hamadani (University of Texas at Austin) 13:00-14:00 Lunch and poster session 14:00-15:20 Session 3 – Chaired by Dr James Fox (Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge) In the Thick of It: Auerbach, Kossoff and the Landscape of Postwar Painting Lee Hallman (The Graduate Center, CUNY) Sculpture into Painting: John Hoyland and New Shape Sculpture in the Early 1960s Sam Cornish (The John Hoyland Estate) Painting as a Citational Practice in the 1960s and After Dr Catherine Spencer (University of St Andrews) 15:20-15:50 Tea break 15:50-17:00 Keynote paper and discussion Two Cultures? Patrick Heron, Lawrence Alloway and a Contested -

Where's the Criticality, Tracey? a Performative Stance Towards

Where’s the Criticality, Tracey? A Performative Stance Towards Contemporary Art Practice Sarah Loggie 2018 Colab Faculty of Design and Creative Technologies An exegesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Creative Technologies Karakia Timatanga Tukua te wairua kia rere ki ngā taumata Hai ārahi i ā tātou mahi Me tā tātou whai i ngā tikanga a rātou ma Kia mau kia ita Kia kore ai e ngaro Kia pupuri Kia whakamaua Kia tina! TINA! Hui e! TAIKI E! Allow one’s spirit to exercise its potential To guide us in our work as well as in our pursuit of our ancestral traditions Take hold and preserve it Ensure it is never lost Hold fast. Secure it. Draw together! Affirm! 2 This content has been removed by the author due to copyright issues Figure A-1 My Bed, Tracey Emin, 1998, Photo: © Tracey Emin/Tate, London 2018 R 3 Figure B-1, 18-06-14, Sarah Loggie, 2014, Photo: © Sarah Loggie, 2018 4 Abstract Tracey Emin’s bed is in the Tate Museum. Flanked by two portraits by Francis Bacon, My Bed (1998) is almost inviting. Displayed on an angle, it gestures for us to climb under the covers, amongst stained sheets, used condoms and empty vodka bottles - detritus of Emin’s life. This is not the first time My Bed has been shown in the Tate. The 2015-17 exhibitions of this work are, in a sense, a homecoming, reminiscent of the work’s introduction to the British public. -

Frank Bowling, Press Release 2017

FRANK BOWLING September 23, 2017 Marc Selwyn Fine Art is pleased to announce an exhibition of paintings by Frank Bowling, O.B.E., RA, opening September 23, 2017. Works in the exhibition range from the artist’s mid- 1970’s poured paintings to his recent canvases, which respond to American Abstract Expressionism with a wider diversity of technique and composition. Early pieces in the exhibition include prime examples of Bowling’s poured paintings in which the artist developed a unique mechanism to tilt the canvas, sending his acrylic medium flowing downward in spontaneous fusions of color. As Mel Gooding writes, “In their thrilling unpredictability, and their vertiginous disposition of the pure materials of their art, these poured paintings have about them something very close to the free-form excitement of contemporaneous advanced New York jazz, itself a brilliant manifestation of the modernist spirit.” Within a year, Bowling began to experiment again, producing more atmospheric works, recalling masters of the English landscape tradition such as Gainsborough and Turner. In Plunge, 1979 for example, clouds of sienna, aqua, muted yellow and pink are diffused in an ethereal composition made with pearl essence and chemical interventions. In more recent paintings, Bowling has added found objects, layers of canvas collage and experimental materials to his repertoire often using a highly personal sun drenched palette. In East Gate with Iona, 2013, horizontal bands of color recall Rothko’s compositions and become the background for a painterly flow of yellows and pinks. In Innerspace, 2012, thin veils of translucent color bring to mind the curtain-like washes of Morris Loius’s paintings of the 1960’s. -

Mike Nelson Full

MIKE NELSON BORN 1967 Loughborough, United Kingdom Lives and works in London EDUCATION 1992-93 Chelsea College of Art & Design, MA Sculpture 1986-90 Reading University, BA (Hons) Fine Art - first class SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 ‘PROJEKTÖR (Gürün Han)’, Protocinema, Istanbul, Turkey ‘Tate Britain Commission’, Tate Britain, London, United Kingdom 2018 Officine Grandi Riparazioni, Turin, Italy ‘Lionheart’, The New Art Gallery Walsall, Walsall, England 2017 ‘A52’, Capri, Düsseldorf, Germany ‘Procession, process. Progress, progression. Regression, recession. Recess, regress’, Galleria Franco Moero, Torino, Italy 2016 ‘Cloak’, Nouveau Musée National de Monaco, Monaco ‘Sensory Spaces 8’, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam ‘Imperfect Geometry for a Concrete Quarry’, Kalkbrottet, Limhamn, Malmö ‘Tools That See’, Neugerriemschneider, Berlin, Germany 2015 303 Gallery, New York, NY Artangel, London, United Kingdom 2014 ‘Studio apparatus for Kunsthalle Münster’, Kunsthalle Münster, Germany ’80 Circles through Canada’ Tramway, Glasgow ‘Amnesiac Hide’ The Power Plant, Toronto, Canada 2013 ‘Mike Nelson’ Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver, Canada 'More things (To the memory of Honoré de Balzac)', Matt's Gallery, London 'M6', Eastside Projects, Birmingham, United Kingdom 2012 Malmo Konsthall, Malmo, Sweden 2011 54th Venice Biennale, British Pavilion, Venice, Italy 2010 303 Gallery, New York, NY 2009 'Triptych', Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin, Ireland ‘The caves of misplaced geometry’, Galleria Franco Noero, Torino, Italy ‘Kristus och Judas: a structural -

Annual Report 2019/2020 Contents II President’S Foreword

Annual Report 2019/2020 Contents II President’s Foreword IV Secretary and Chief Executive’s Introduction VI Key figures IX pp. 1–63 Annual Report and Consolidated Financial Statements for the year ended 31 August 2020 XI Appendices Royal Academy of Arts Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD Telephone 020 7300 8000 royalacademy.org.uk The Royal Academy of Arts is a registered charity under Registered Charity Number 1125383 Registered as a company limited by a guarantee in England and Wales under Company Number 6298947 Registered Office: Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD © Royal Academy of Arts, 2020 Covering the period Portrait of Rebecca Salter PRA. Photo © Jooney Woodward. 1 September 2019 – Portrait of Axel Rüger. Photo © Cat Garcia. 31 August 2020 Contents I President’s I was so honoured to be elected as the Academy’s 27th President by my fellow Foreword Academicians in December 2019. It was a joyous occasion made even more special with the generous support of our wonderful staff, our loyal Friends, Patrons and sponsors. I wanted to take this moment to thank you all once again for your incredibly warm welcome. Of course, this has also been one of the most challenging years that the Royal Academy has ever faced, and none of us could have foreseen the events of the following months on that day in December when all of the Academicians came together for their Election Assembly. I never imagined that within months of being elected, I would be responsible for the temporary closure of the Academy on 17 March 2020 due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.