Excerpts About SLA Marshall (SLAM)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Training Area Dedicated to Warriors I' W I44> 4! H I

www.flw-guidon.com 1 r Volume 6, Number 43 Published in the interest of the personnel at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri Thursday, October 28, 2004 J c ( per a a s 'r iL 11.J1. Y_ J Training area dedicated to warriors I' w I44> 4! h i ., them and to their commander, retired Col. Wood, Maj. Gen. Randal Castro, com- "Sometimes ig SKorean War chargers we don't realize how great Lewis Millett, during a ceremony held Oct manding general, and Command Sgt. Maj. it is to be an American citizen," he added. u, . y ; have legacy enshrined 20. William McDaniel, installation command "The honor and privilege to wear the uni- .. .. The charge, called "Operation Thun- sergeant major. form of the U.S. Army is worth the sacri- for future generations derbolt" took place at Hill 180, Korea on "More than 30,000 Soldiers a year will fice." Basic training Feb. 7, 1951, and was the last bayonet as- pass through Bayonet Hill," said Staff Sgt. Army values played a major role in what By Spe. Tremeshia Ellis sault the Army conducted in modem mili- Keith Follin, the training area's noncom- this man and leader stands for, Castro told Drill sergeants push GUIDON staff tary history. missioned officer in charge. "Every single the audience, including the company of ini- new Soldiers as they According to officials, the training basic training Soldier goes through this tial entry Soldiers about to complete the become America's Fix bayonets! Let's go! Follow me! area's name change reflects the mission of course." bayonet course. -

Tropic Lightning News Can Be Found At

Full Issues of the Tropic Lightning News can be found at https://www.25thida.org/TLN 7 January 1966 'Tropic Lightning' Div. Answers 'Call To Arms' 4000 Men Depart For Viet-Nam The jungle and guerrilla warfare trained 3rd Bde, of Hawaii's own Tropic Lightning Division, departed for Viet-Nam last week in keeping with the 25th's motto, "Ready to Strike, Anywhere, Anytime." The 25th Inf. Div. moved the 4,000-man task force to the war-torn area by sea and air transports. The fresh troops sporting the division's arm patch bearing a bolt of lightning, is under the command of 46-year-old Col. Everette A. Stoutner. The 3rd Bde is the first major force of the 25th Division to be committed in Viet-Nam, although C Co., 65th Engr. Bn., has been on duty in RVN since August and some of the division's "Shotgunners" are still on duty there. Colonel Stoutner, after arriving in Viet-Nam's central highlands, where infiltration by North Viet-Namese forces has been the heaviest, said, "We've been waiting to come here for a long time," and "we're real glad to be here." Brig. Gen. Charles A. Symrosky, who greeted the troops as they arrived in Viet-Nam via airlift, said the brigade's mission will be "to conduct offensive operations in the highlands." The general remarked, "These are fighting men in a real fighting situation." The Brigade Task Force is composed of the 1st and 2nd Bns., 35th Inf. (Cacti); 1/14th Inf . (Golden Dragons; 2/9th Arty (Mighty Ninth); C Trp., (See 3rd Bde Page 4) BATTLE BOUND - A 3rd Bde, 25th Inf. -

Memorial Day 2021

MEMORIAL DAY 2021 Virgil Poe and RC Pelton This article is dedicated to the families and friends of all soldiers, sailors and Marines who did not survive war and those who did survive but suffered with battle fatigue Shell Shock, or PTSD . Virgil Poe served in the US ARMY DURING WORLD WAR ll. HE WAS IN THE BATTLE OF THE BULGE AS WAS MY UNCLE LOWELL PELTON. As a teenager, Virgil Poe, a 95 year old WWII veteran served in 3rd army and 4th army in field artillery units in Europe (France, Belgium Luxemburg, and Germany) He recently was awarded the French Legion of Honor for his WWII service. Authorized by the President of France, it is the highest Military Medal in France. After the war in Germany concluded, he was sent to Fort Hood Texas to be reequipped for the invasion of Japan. But Japan surrendered before he was shipped to the Pacific. He still calls Houston home. Ernest Lowell Pelton My Uncle Ernest Lowell Pelton was there with Virgil during the battle serving as a Medic in Tank Battalion led by General Gorge Patton. During the battle he was wounded while tending to 2 fellow soldiers. When found they were both dead and Lowell was thought dead but still barely alive. He ended up in a hospital in France where he recovered over an 8-month period. He then asked to go back to war which he did. Lowell was offered a battlefield commission, but declined saying, I do not want to lead men into death. In Anson Texas he was called Major since all the small-town residents had heard of his heroism. -

Shootout on the Cambodian Border

Shootout on the Cambodian Border 11 November 1966 Colonel (Ret.) Phil Courts [email protected] “CROC 6” 119th AHC Pleiku, RVN SAIGON, South Viet Nam (AP).....” Headquarters also announced that three American helicopters were shot down Friday while supporting ground operations near the Plei Djereng Special Forces camp in the highlands close to the Cambodian border”. 11 November 1966 was a busy and dangerous time for US Forces in Vietnam. It’s not surprising that the AP made only brief mention to what I’m calling “The Shootout on the Cambodian Border”. That same day five U.S. planes were lost over North Vietnam; Viet Cong infiltrators inflicted heavy casualties on a platoon of American Marines near Da Nang; an ammunition dump near Saigon was blown up and the 45th Surgical Hospital was mortared. Add to this at least five other helicopters, two of them medevac flights, and an F-100 were shot down in the south and a CV-2 Caribou crashed in a rainstorm. This “War Story” looks in detail at the bravery, sacrifice and skill of the three crews shot down some forty- eight years ago at LZ “Red Warrior”. Forty-eight years is a long time to remember an event that lasted no more than ten minutes, but for those who participated in the “Shootout on the Cambodian Border” or the “Pail Wail Doodle” as noted military historian S.L.A. Marshall called it, it was only yesterday. On 11 November 1966 I was serving as the platoon leader of the gunship platoon (Call Sign Croc 6) of the 119th AHC. -

ORAL HISTORY Lieutenant General John H. Cushman US Army, Retired

ORAL HISTORY Lieutenant General John H. Cushman US Army, Retired VOLUME FOUR TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Title Pages Preface 1 18 Cdr Fort Devens, MA 18-1 to 18-18 19 Advisor, IV Corps/Military Region 4, Vietnam 19-1 to 19A-5 20 Cdr 101st Airborne Division & Fort Campbell, KY 20-1 to 20-29 Preface I began this Oral History with an interview in January 2009 at the US Army Military History Institute at Carlisle Barracks, PA. Subsequent interviews have taken place at the Knollwood Military Retirement Residence in Washington, DC. The interviewer has been historian Robert Mages. Until March 2011 Mr. Mages was as- signed to the Military History Institute. He has continued the project while assigned to the Center of Military History, Fort McNair, DC. Chapter Title Pages 1 Born in China 1-1 to 1-13 2 Growing Up 2-1 to 2-15 3 Soldier 3-1 to 3-7 4 West Point Cadet 4-1 to 4-14 5 Commissioned 5-1 to 5-15 6 Sandia Base 6-1 to 6-16 7 MIT and Fort Belvoir 7-1 to 7-10 8 Infantryman 8-1 to 8-27 9 CGSC, Fort Leavenworth, KS, 1954-1958 9-1 to 9-22 10 Coordination Group, Office of the Army Chief of Staff 10-1 to 10-8 11 With Cyrus Vance, Defense General Counsel 11-1 to 11-9 12 With Cyrus Vance, Secretary of the Army 12-1 to 12-9 13 With the Army Concept Team in Vietnam 13-1 to 13-15 14 With the ARVN 21st Division, Vietnam 14-1 to 14-19 15 At the National War College 15-1 to 15-11 16 At the 101st Airborne Division, Fort Campbell, KY 16-1 to 16-10 17 Cdr 2d Brigade, 101st Airborne Division, Vietnam 17-1 to 17-35 18 Cdr Fort Devens, MA 18-1 to 18-18 19 Advisor, IV Corps/Military Region 4, Vietnam 19-1 to 19A-5 20 Cdr 101st Airborne Division & Fort Campbell, KY 19-1 to 19-29 21 Cdr Combined Arms Center and Commandant CGSC 22 Cdr I Corps (ROK/US) Group, Korea 23 In Retirement (interviews for the above three chapters have not been conducted) For my own distribution in November 2012 I had Chapters 1 through 7 (Volume One) print- ed. -

Lessons Learned, Headquarters, 1St Cavalry

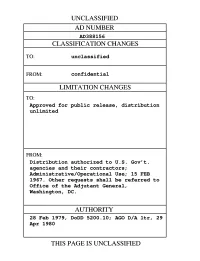

UNCLASSIFIED AD NUMBER AD388156 CLASSIFICATION CHANGES TO: unclassified FROM: confidential LIMITATION CHANGES TO: Approved for public release, distribution unlimited FROM: Distribution authorized to U.S. Gov't. agencies and their contractors; Administrative/Operational Use; 15 FEB 1967. Other requests shall be referred to Office of the Adjutant General, Washington, DC. AUTHORITY 28 Feb 1979, DoDD 5200.10; AGO D/A ltr, 29 Apr 1980 THIS PAGE IS UNCLASSIFIED Best Avai~lable Copy SECURITY MARKING The classified or limited status of this repol applies to each page, unless otherwise marked. Separate page, printouts MUST be marked accordingly. THIS DOCUMENT CONTAINS INFORMATION AFFECTING THE NATIONAL DEFENSE OF THE UNITED STATES WITHIN THE MEANING OF THE ESPIONAGE LAWS, TITLE 18, U.S.C., SECTIONS 793 AND 794. THE TRANSMISSION OR THE REVELATION OF ITS CONTENTS IN ANY MANNER TO AN UNAUTHORIZED PERSON IS PROHIBITED BY LAW. NOTICE: When government or other drawings, specifications or other data are used for any purpose other than in connection with a defi- nitely related government procurement operation, the U. S. Government thereby incurs no responsibility, nor any obligation whatsoever; and the fact that the Government may have formulated, furnished, or in any way supplied the said drawings, specifications, or other data is not to be regarded by implication or otherwise a; in any manner licensing the holder or any other person or corporation, or conveying any rights or permission to manufacture, use or sell any patented invention that may in any way be related thereto. DEPARTMENT OFT A OFFICE OF THE ADJUTANT GENERAL WASHINGTON, D.C. 20310 IN REPY REFE'R O 00 SUBJECT: Ls Learned, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) - --- ,,- TO:~SEE DISTRIBUTION 0i > I. -

Published Doctoral Dissertations

Dissertations by Students of Dallas Baptist University Date Num. Name Dissertation Topic Methodology Published 1 2008 Dr. Jeanie Johnson Ed.D. The Effect of School Based Physical Activity and Obesity on Academic Achievement Quant The Impact of Leadership Styles of Special Education Administrators in Region 10 on Performance-Based Monitoring Analysis 2 2009 Dr. Gloria Key Ed.D. Quant System 3 2009 Dr. Emily Prevost Ph.D. Quality of Life for Texas Baptist Pastors Quant 4 2009 Dr. Thomas Sanders Ph.D. The Kingdom of God Belongs to Such as These: Exploring the Conversion Experiences of Baptist Children Qual 5 2009 Dr. Larry Taylor Ph.D. A Study of the Biblical Worldview of Twelfth Grade Students from Christian and Public High School Quant Comparison of Music Based Curriculum Versus an Eclectic Curriculum for Speech Acquisition in Students with Autism Spectrum 6 2010 Dr. Kaye Tindell Ed.D. Quant Disorder Alternative and Traditional Certified Elementary Teachers: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of their First Year in the Classroom 7 2010 Dr. Jerry Burkett Ed.D. Quant Environment A Study of the Relationship Between the Developmental Assets Framework and the Academic Success of At-Risk Elementary 8 2010 Dr. Courtney Jackson Ed.D. Quant to Middle School Transitioning Students The Impact of Administratively Implemented and Facilitated Structured Collaboration on Teachers Collective and Personal 9 2010 Dr. James Roe Ed.D. Quant Efficacy and Student Achievement 10 2010 Dr. Evelyn Ashcraft Ph.D. An Examination of Texas Baptist Student Ministry Participation and Post-collegiate Ministry Activity Quant Leader Character Quality, Goal Achievement, Psychological Capital, and Spirituality among the American Physical Therapy 11 2010 Dr. -

Wolfhoun-O Reflections V

WOLFHOUN-O REFLECTIONS V We're moving right along with our tales of the people and events which have made, and continue to make, the Wolfhounds such a unique organization. Just back from Sinai after a six month "holiday" with the Second Battalion is SSG Rob Stewart .. a big help in the past and sure to be one again. He has already breathed life into what appeared on the surface to be a boring, humdrum tour. We're proud of the Battalion's record there! We're also grateful to SOT Ralph Strickland, First Battalion's chaplain's assistant, for his help. We've been hearing from a few more Wolfhounds ... and have already used some of their stories. The history of the regiment is downright fascinating, especially when you get down to the individual level. And speaking of individuals, say a prayer for that great Wolfhound Colonel Lewis Millett ... he's a bit under the weather. If you have any reflections you'd like to share with other Wolfhounds, send 'em along. We'll try to publish them. Hugh O'Reilly Honorary Regimental Sergeant Major February 1997 WOLFHOUND MEDALS OF HONOR PHILIPPINE INSURRECTION 1LT Charles G. Bickman 1LT George G. Shaw WORLD WAR II CPT Charles W. Davis SSG Raymond H. Cooley KOREAN WAR *CPL John W. Collier "'CPT Reginald B Desiderio CPT Lewis L. Millett *2LT Jerome A. Sudut "'CPL Benito Martinez VIETNAM WAR SOT John F. Baker, Jr. CPT Robert F. Foley "'SOT Charles C. Fleek *CPT Riley L. Pitts SSG Paul R. Lambers "'POSTHUMOUS AWARD CORRECTIONS AND ADDITIONS In our haste to complete "Reflections III" we failed to get the complete story on Sandbag Castle, where Benito Martinez earned the Medal of Honor in the Korean War. -

Inside St. George Summer 2021

INSIDE SUMMER 2021 WELCOME TO ST. GEORGE, IRONMAN 70.3 COMPETITORS! CITY NEWS | ACTIVITIES | PROGRAMS | INFORMATION | PROGRAMS ACTIVITIES | NEWS CITY INSIDE SUMMER 2021 3 MAYOR RANDALL’S MESSAGE By Mayor Michele Randall 4 SUMMER ENERGY CONSERVATION CAMPAIGN MAYOR RANDALL’S By David Cordero MESSAGE 6 A PLACE OF HONOR, A PLACE TO SEEK SOLACE By David Cordero 8 TIME TO HONOR, REMEMBER OUR KOREAN WAR VETERANS By David Cordero 10 QUIET REVELATIONS FROM Look at the red rocks of Snow Canyon State of sunshine each year, and we are known THUNDER JUNCTION Park. Then glance to the north, where the throughout the region for our enthusiastic majestic Pine Valley mountains rest. Take a volunteers. But I think it is more than that. By Michelle Graves short climb onto the sugarloaf at Pioneer Park, IRONMAN competitors are known for their and gaze out over the thriving city below. hard work, sacrifice, and determination— 12 CITY BEAT traits that characterized the early pioneers A quick look at current City news LWe are surrounded by natural beauty. who settled St. George in 1862. The result of their toil in the harsh desert is a sense of I am blessed to call St. George, Utah, home accomplishment that runs deep. VOICES | CITY MESSAGE RANDALL’S MAYOR 14 CITY LIFE and delighted when others from around the country—and often, around the world—take We have been fortunate to host IRONMAN What’s going on around St. George? precious time from their lives to visit. Southern races since 2010. We are especially thrilled to Utah is a special place, not only because of have it back in our town after the pandemic- 18 MAYOR’S LOOP: A JEWEL AMID THE the eye-popping grandeur that seems to be riddled 2020. -

History of T:Ic

I I (II .. ~/ \ '-~ .. J, ... 1, ! , , - HISTORY OF T:IC 155TH AVIATION COO:ji;: iL"ii.) 1 JANUARY 1966 - 31 DE(;:o!::JDZIl 1966 .. .~." .. .. ... ~-- ....... - ... o ~-'- --.~ -- . ,-' HISTORY OF THE 1;5T~{ AVIATION COMPANY (ANL) APO SA:':-T FRANCISCO, 96297 1 JA~mARY 1966 - 31 DECEMBER 1966 Prepared by Unit Historian and Assistant 1LT ilillis J. Heydenberk \-101 Paul G.' Coke Ap"roved by ROBERT V. ATKr'SON Haj Inf J 52D COMBAT AVIATION BATTALION APO San Franoisoo, 96318 ._ .. I () (J . '_. TABLE OF- CONTEnS _.' , _., •• ~ •• -'F"' .. ' ._-' List of Illustratinns Forward Prafo.co I. l1ission and Resources l1ission 1 Organization 1 Regioncl ~nnlysis 2 II. Significnnt Events and Or>erntions: 1966 , "";' .. " 1 January - 31 March 5 1 April - 30 June 8 1 July - 30 September 11 1 October - 31 December 15 III.Statistics 18 ItT. Appendix Linoage 19 Roster of Key Parsonnel 20 • l~ps of Significant Oner~tional Arons , (J LIST OF ILLUSTP.ATIONS I HAP: Nort".ern Cen.tM.l Flatea't!, Republic "f Viet --Nem Indicating areas involving: Operation PAUL REVERE I - IV 16 April 1966 - 31 December 1966 Miosion in sup-oort of Special Forces, IContum 23 October 1966 - 9 November 1966 II MAP: Southern Central Plateau, Republic of Viet Nam Indicating areaa involving: Sector Bupnort and various airlifts of the 23D Division ARVN Operation Ol-lEGA 12 ~Iovember 1966 - 3 Decmber 1966 ':'.,-. Maps included in initial copy only. .. .J "lh..... _ ........ _ •.• -.~-".--.~.-----------'.--.'.-. I ---~ -- -----.- () o FOR'IA.."l.D Serving as a combat su"nort a-;ia tion unit in the Remlbllc "f net 'Yam, the 155th Avia tion Com~any (Al1L), wi tl-J its supporting detach ments, is similar to the many other aviation units of the same size and structure. -

Chief's File Cabinet

CHIEF’S FILE CABINET Ronny J. Coleman ____________________________________ Lazy Boy Learning Colonel David Hackworth was one of the most decorated soldiers of the Vietnam War. He earned over ninety service decorations, which consisted of both personal and organizational citations. After he retired he wrote a book, with author Julie Sherman entitled “About Face: the Odyssey of an American Warrior”. 1In that book he touts the theory that every fire officer in this country needs to literally understand. His admonition to all of those who are going to take people into combat was “practice doesn’t make perfect – it makes it permanent…..” And “Sweat in training saves blood on the battlefield." In other words, what the Colonel was telling us then was that repetition over and over again does not make us perfect especially if the repetition is done improperly or inappropriately. Repeating mistakes of the past is simply not an effective strategy of being able to predict future performance. No where can this be any truer than in the concept of training of our firefighters for their role in combat. If you are like me you are probably getting very frustrated with reading continuous stories about firefighters being killed or worse yet badly injured at the scenes of fires. And probably the worst of all is when you read a story about a firefighter dying in a training exercise. In almost all cases practice did not make it perfect for these individuals. What is being made permanent, is their death and/or long term recovery from something that could or should have never happened in the first place. -

Video File Finding

Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum (714) 983 9120 ◦ http://www.nixonlibrary.gov ◦ [email protected] MAIN VIDEO FILE ● MVF-001 NBC NEWS SPECIAL REPORT: David Frost Interviews Henry Kissinger (10/11/1979) "Henry Kissinger talks about war and peace and about his decisions at the height of his powers" during four years in the White House Runtime: 01:00:00 Participants: Henry Kissinger and Sir David Frost Network/Producer: NBC News. Original Format: 3/4-inch U-Matic videotape Videotape. Cross Reference: DVD reference copy available. DVD reference copy available ● MVF-002 "CNN Take Two: Interview with John Ehrlichman" (1982, Chicago, IL and Atlanta, GA) In discussing his book "Witness to Power: The Nixon Years", Ehrlichman comments on the following topics: efforts by the President's staff to manipulate news, stopping information leaks, interaction between the President and his staff, FBI surveillance, and payments to Watergate burglars Runtime: 10:00 Participants: Chris Curle, Don Farmer, John Ehrlichman Keywords: Watergate Network/Producer: CNN. Original Format: 3/4-inch U-Matic videotape Videotape. DVD reference copy available ● MVF-003 "Our World: Secrets and Surprises - The Fall of (19)'48" (1/1/1987) Ellerbee and Gandolf narrate an historical overview of United States society and popular culture in 1948. Topics include movies, new cars, retail sales, clothes, sexual mores, the advent of television, the 33 1/3 long playing phonograph record, radio shows, the Berlin Airlift, and the Truman vs. Dewey presidential election Runtime: 1:00:00 Participants: Hosts Linda Ellerbee and Ray Gandolf, Stuart Symington, Clark Clifford, Burns Roper Keywords: sex, sexuality, cars, automobiles, tranportation, clothes, fashion Network/Producer: ABC News.