Snakes of “Snake Road” John G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cfreptiles & Amphibians

WWW.IRCF.ORG/REPTILESANDAMPHIBIANSJOURNALTABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES & IRCFAMPHIBIANS REPTILES • VOL 15,& NAMPHIBIANSO 4 • DEC 2008 •189 20(4):166–171 • DEC 2013 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS FEATURE ARTICLES Differential. Chasing Bullsnakes (Pituophis catenifer sayiHabitat) in Wisconsin: Use by Common On the Road to Understanding the Ecology and Conservation of the Midwest’s Giant Serpent ...................... Joshua M. Kapfer 190 . The Shared History of Treeboas (Corallus grenadensis) and Humans on Grenada: A WatersnakesHypothetical Excursion ............................................................................................................................ (Nerodia sipedonRobert W. Henderson) 198 Lorin A.RESEARCH Neuman-Lee ARTICLES1,2, Andrew M. Durso1,2, Nicholas M. Kiriazis1,3, Melanie J. Olds1,4, and Stephen J. Mullin1 . The Texas Horned Lizard in Central and Western Texas ....................... Emily Henry, Jason Brewer, Krista Mougey, and Gad Perry 204 1Department of Biological Sciences, Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, Illinois 61920, USA . The Knight Anole (Anolis equestris) in Florida 2 Present ............................................. address: DepartmentBrian of Biology,J. Camposano, Utah Kenneth State L. University, Krysko, Kevin Logan, M. Enge, Utah Ellen 84321,M. Donlan, USA and ([email protected]) Michael Granatosky 212 3Present address: School of Teacher Education and Leadership, Utah State University, Logan, Utah 84321, USA CONSERVATION4Present -

Yellow-Bellied Water Snake Plain-Bellied Water

Nature Flashcards Snakes All photos are subject to the terms of the Creative Commons Public License Based on Nature Quiz Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 United States unless copyright otherwise By Phil Huxford noted. TMN-COT Meeting November, 2013 Texas Master Naturalist Cradle of Texas Chapter Cradle of Texas Chapter Yellow-bellied Water Snake Plain-bellied Water Snake Nerodia erythrogaster flavigaster Elliptical eye pupils Bright yellow underneath Found around ponds, lakes, swamps, and wet bottomland forests 2 – 3 feet long Cradle of Texas Chapter Broad-banded Water snake Nerodia fasciata confluens Dark, wide bands separated by yellow Bold, dark checked stripes Strong swimmer Cradle of Texas Chapter 2 – 4 feet long Blotched Water Snake Nerodia erythrogaster transversa Black-edged; dark brown dorsal markings Yellow or sometimes orange belly Lives in small ponds, ditches, and rain-filled pools Typically 2 – 5 feet long Cradle of Texas Chapter Diamond-back Water Snake Northern Diamond-back Water Snake Nerodia rhombifer Heavy-bodied, large girth Can be dark brown Head somewhat flattened and wide Texas’ largest Nerodia Strikes without warning and viciously 4 – 6’ long Cradle of Texas Chapter Photo by J.D. Wilson http://srelherp.uga.edu/snakes/ Western Mud Snake Mud Snake Farancia abacura Lives in our area but rarely seen Glossy black above Red belly with black lines in belly Found in wooded swampland and wet areas Does not bite when handled but pokes tail like stinger 3 – 4 feet long Cradle of Texas Chapter Texas Coral Snake Micrurus fulvius tenere Blunt head; shiny, slender body Round pupils Colors red, yellow, black Lives in partly wooded organic material Cradle of Texas Chapter Usually 2 – 3 feet long Record: 47 ¾ inches in Brazoria County ‘Red touches yellow – kill a fellow. -

Amphibians Present in the Barataria Preserve of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve

Amphibians present in the Barataria Preserve of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve. The species list was generated from data compiled from NPS observations and during a 2001-2002 reptile and amphibian inventory conducted by Noah J. Anderson and Dr. Richard A. Seigel, Southeastern Louisiana University, Hammond, Louisiana. Common Name Scientific Name Habitat Association Smallmouth salamander Ambystoma texanum hardwood forests Three-toed amphiuma Amphiuma tridactylum swamp, marsh, restricted to aquatic habitats in hardwood forests Dwarf salamander Eurycea quadridigitata hardwood forests, marsh Eastern newt Notophthalmus viridescens found in and near aquatic habitats Southern dusky salamander Desmognathus auriculatus hardwood forests Lesser siren Siren intermedia swamp, marsh Northern cricket frog Acris crepitans all habitats Gulf coast toad Bufo valliceps all habitats Greenhouse frog Eleutherodactylus planirostris hardwood forests Eastern narrowmouth toad Gastrophryne carolinensis all habitats Bird-voiced treefrog Hyla avivoca hardwood forests, swamp Green treefrog Hyla cinerea all habitats Squirrel treefrog Hyla squirella swamp, hardwood forests Spring peeper Pseudacris crucifer swamp, hardwood forests Chorus frog Pseudacris triseriata hardwood forests, swamp Bullfrog Rana catesbeiana hardwood forests, swamp Bronze frog Rana clamitans all habitats Pig frog Rana grylio marsh Southern leopard frog Rana sphenocephala swamp, marsh Reptiles present in the Barataria Preserve of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve. -

Bibliography and Scientific Name Index to Amphibians

lb BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SCIENTIFIC NAME INDEX TO AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN THE PUBLICATIONS OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON BULLETIN 1-8, 1918-1988 AND PROCEEDINGS 1-100, 1882-1987 fi pp ERNEST A. LINER Houma, Louisiana SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE NO. 92 1992 SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE The SHIS series publishes and distributes translations, bibliographies, indices, and similar items judged useful to individuals interested in the biology of amphibians and reptiles, but unlikely to be published in the normal technical journals. Single copies are distributed free to interested individuals. Libraries, herpetological associations, and research laboratories are invited to exchange their publications with the Division of Amphibians and Reptiles. We wish to encourage individuals to share their bibliographies, translations, etc. with other herpetologists through the SHIS series. If you have such items please contact George Zug for instructions on preparation and submission. Contributors receive 50 free copies. Please address all requests for copies and inquiries to George Zug, Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 20560 USA. Please include a self-addressed mailing label with requests. INTRODUCTION The present alphabetical listing by author (s) covers all papers bearing on herpetology that have appeared in Volume 1-100, 1882-1987, of the Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington and the four numbers of the Bulletin series concerning reference to amphibians and reptiles. From Volume 1 through 82 (in part) , the articles were issued as separates with only the volume number, page numbers and year printed on each. Articles in Volume 82 (in part) through 89 were issued with volume number, article number, page numbers and year. -

Checklist Reptile and Amphibian

To report sightings, contact: Natural Resources Coordinator 980-314-1119 www.parkandrec.com REPTILE AND AMPHIBIAN CHECKLIST Mecklenburg County, NC: 66 species Mole Salamanders ☐ Pickerel Frog ☐ Ground Skink (Scincella lateralis) ☐ Spotted Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) palustris) Whiptails (Ambystoma maculatum) ☐ Southern Leopard Frog ☐ Six-lined Racerunner ☐ Marbled Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) sphenocephala (Aspidoscelis sexlineata) (Ambystoma opacum) (sphenocephalus)) Nonvenomous Snakes Lungless Salamanders Snapping Turtles ☐ Eastern Worm Snake ☐ Dusky Salamander (Desmognathus fuscus) ☐ Common Snapping Turtle (Carphophis amoenus) ☐ Southern Two-lined Salamander (Chelydra serpentina) ☐ Scarlet Snake1 (Cemophora coccinea) (Eurycea cirrigera) Box and Water Turtles ☐ Black Racer (Coluber constrictor) ☐ Three-lined Salamander ☐ Northern Painted Turtle ☐ Ring-necked Snake (Eurycea guttolineata) (Chrysemys picta) (Diadophis punctatus) ☐ Spring Salamander ☐ Spotted Turtle2, 6 (Clemmys guttata) ☐ Corn Snake (Pantherophis guttatus) (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus) ☐ River Cooter (Pseudemys concinna) ☐ Rat Snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) ☐ Slimy Salamander (Plethodon glutinosus) ☐ Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) ☐ Eastern Hognose Snake ☐ Mud Salamander (Pseudotriton montanus) ☐ Yellow-bellied Slider (Trachemys scripta) (Heterodon platirhinos) ☐ Red Salamander (Pseudotriton ruber) ☐ Red-eared Slider3 ☐ Mole Kingsnake Newts (Trachemys scripta elegans) (Lampropeltis calligaster) ☐ Red-spotted Newt Mud and Musk Turtles ☐ Eastern Kingsnake -

Lake Erie Watersnake (Nerodia Sipedon Insularum) in Canada

PROPOSED Species at Risk Act Management Plan Series Adopted under Section 69 of SARA Management Plan for the Lake Erie Watersnake (Nerodia sipedon insularum) in Canada Lake Erie Watersnake 2019 Recommended citation: Environment and Climate Change Canada. 2019. Management Plan for the Lake Erie Watersnake (Nerodia sipedon insularum) in Canada [Proposed]. Species at Risk Act Management Plan Series. Environment and Climate Change Canada, Ottawa. 2 parts, 28 pp. + 20 pp. For copies of the management plan, or for additional information on species at risk, including the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry1. Cover illustration: © Gary Allen Également disponible en français sous le titre « Plan de gestion de la couleuvre d’eau du lac Érié (Nerodia sipedon insularum) au Canada [Proposition] » © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Environment and Climate Change, 2019. All rights reserved. ISBN Catalogue no. Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source. 1 www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/species-risk-public-registry.html MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR LAKE ERIE WATERSNAKE (Nerodia sipedon insularum) IN CANADA 2019 Under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996), the federal, provincial, and territorial governments agreed to work together on legislation, programs, and policies to protect wildlife species at risk throughout Canada. In the spirit of cooperation of the Accord, the Government of Ontario has given permission to the Government of Canada to adopt the Blue Racer, Lake Erie Watersnake and Small-mouthed Salamander and Unisexual Ambystoma (Small- mouthed Salamander dependent population) – Ontario Government Response Statement (Part 2) under Section 69 of the Species at Risk Act (SARA). -

211356675.Pdf

306.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SERPENTES: COLUBRIDAE STORERIA DEKA YI Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. and western Honduras. There apparently is a hiatus along the Suwannee River Valley in northern Florida, and also a discontin• CHRISTMAN,STEVENP. 1982. Storeria dekayi uous distribution in Central America . • FOSSILRECORD. Auffenberg (1963) and Gut and Ray (1963) Storeria dekayi (Holbrook) recorded Storeria cf. dekayi from the Rancholabrean (pleisto• Brown snake cene) of Florida, and Holman (1962) listed S. cf. dekayi from the Rancholabrean of Texas. Storeria sp. is reported from the Ir• Coluber Dekayi Holbrook, "1836" (probably 1839):121. Type-lo• vingtonian and Rancholabrean of Kansas (Brattstrom, 1967), and cality, "Massachusetts, New York, Michigan, Louisiana"; the Rancholabrean of Virginia (Guilday, 1962), and Pennsylvania restricted by Trapido (1944) to "Massachusetts," and by (Guilday et al., 1964; Richmond, 1964). Schmidt (1953) to "Cambridge, Massachusetts." See Re• • PERTINENT LITERATURE. Trapido (1944) wrote the most marks. Only known syntype (Acad. Natur. Sci. Philadelphia complete account of the species. Subsequent taxonomic contri• 5832) designated lectotype by Trapido (1944) and erroneously butions have included: Neill (195Oa), who considered S. victa a referred to as holotype by Malnate (1971); adult female, col• lector, and date unknown (not examined by author). subspecies of dekayi, Anderson (1961), who resurrected Cope's C[oluber] ordinatus: Storer, 1839:223 (part). S. tropica, and Sabath and Sabath (1969), who returned tropica to subspecific status. Stuart (1954), Bleakney (1958), Savage (1966), Tropidonotus Dekayi: Holbrook, 1842 Vol. IV:53. Paulson (1968), and Christman (1980) reported on variation and Tropidonotus occipito-maculatus: Holbrook, 1842:55 (inserted ad- zoogeography. Other distributional reports include: Carr (1940), denda slip). -

Snakes of the Everglades Agricultural Area1 Michelle L

CIR1462 Snakes of the Everglades Agricultural Area1 Michelle L. Casler, Elise V. Pearlstine, Frank J. Mazzotti, and Kenneth L. Krysko2 Background snakes are often escapees or are released deliberately and illegally by owners who can no longer care for them. Snakes are members of the vertebrate order Squamata However, there has been no documentation of these snakes (suborder Serpentes) and are most closely related to lizards breeding in the EAA (Tennant 1997). (suborder Sauria). All snakes are legless and have elongated trunks. They can be found in a variety of habitats and are able to climb trees; swim through streams, lakes, or oceans; Benefits of Snakes and move across sand or through leaf litter in a forest. Snakes are an important part of the environment and play Often secretive, they rely on scent rather than vision for a role in keeping the balance of nature. They aid in the social and predatory behaviors. A snake’s skull is highly control of rodents and invertebrates. Also, some snakes modified and has a great degree of flexibility, called cranial prey on other snakes. The Florida kingsnake (Lampropeltis kinesis, that allows it to swallow prey much larger than its getula floridana), for example, prefers snakes as prey and head. will even eat venomous species. Snakes also provide a food source for other animals such as birds and alligators. Of the 45 snake species (70 subspecies) that occur through- out Florida, 23 may be found in the Everglades Agricultural Snake Conservation Area (EAA). Of the 23, only four are venomous. The venomous species that may occur in the EAA are the coral Loss of habitat is the most significant problem facing many snake (Micrurus fulvius fulvius), Florida cottonmouth wildlife species in Florida, snakes included. -

Survey of Caledon Natural Area State Park

Survey of Caledon Natural Area State Park David A. Perry 316 Taylor Ridge Way Palmyra, VA 22963 Introduction Caledon Natural Area was originally established as Caledon plantation in 1659 by the Alexander family, founders of the city of Alexandria, Virginia. It remained in private hands until it was donated to the Com- monwealth in 1974 by Mrs. Ann Hopewell Smoot. In 1981, the Caledon Task Force was appointed by Governor Robb to develop a management plan for Caledon to help protect the summering bald eagle popu- lation. A no-boating zone along the Potomac shoreline, limited public access trails and buffer zones were created to help protect bald eagle habitat. These limits have remained basically in place through August 2012, with some amendments. With the delisting of the bald eagle as an endangered species, plans were developed and approved on April 25, 2012 to expand public access at Caledon. Most likely these plans will be initiated in 2013. Located in King George County, Caledon Natural Area is approximately 37 km (23 miles) east of Freder- icksburg and about 97 km (60 miles) northwest of the confluence of the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay. Within the park boundaries are a total of 1,044 hectares (2,579 acres) of diverse habitat; 953 hectares (2,355 acres) are forested (majority are mixed hardwood with some isolated softwood stands), 10.1 hect- ares (25 acres) are in old fields, 26.3 hectares (65 acres) are ponds and streams, 28.3 hectares (70 acres) are marshes, 6.1 hectares (15 acres) in Potomac shore and beach and 19.4 hectares (48 acres) are considered the original home site. -

Check List 17 (1): 27–38

17 1 ANNOTATED LIST OF SPECIES Check List 17 (1): 27–38 https://doi.org/10.15560/17.1.27 A herpetological survey of Edith L. Moore Nature Sanctuary Dillon Jones1, Bethany Foshee2, Lee Fitzgerald1 1 Biodiversity Research and Teaching Collections, Department of Ecology and Conservation Biology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA. 2 Houston Audubon, 440 Wilchester Blvd. Houston, TX 77079 USA. Corresponding author: Dillon Jones, [email protected] Abstract Urban herpetology deals with the interaction of amphibians and reptiles with each other and their environment in an ur- ban setting. As such, well-preserved natural areas within urban environments can be important tools for conservation. Edith L. Moore Nature Sanctuary is an 18-acre wooded sanctuary located west of downtown Houston, Texas and is the headquarters to Houston Audubon Society. This study compared iNaturalist data with results from visual encounter surveys and aquatic funnel traps. Results from these two sources showed 24 species belonging to 12 families and 17 genera of herpetofauna inhabit the property. However, several species common in surrounding areas were absent. Combination of data from community science and traditional survey methods allowed us to better highlight herpe- tofauna present in the park besides also identifying species that may be of management concern for Edith L. Moore. Keywords Community science, iNaturalist, urban herpetology Academic editor: Luisa Diele-Viegas | Received 27 August 2020 | Accepted 16 November 2020 | Published 6 January 2021 Citation: Jones D, Foshee B, Fitzgerald L (2021) A herpetology survey of Edith L. Moore Nature Sanctuary. Check List 17 (1): 27–28. https://doi. -

Northern Population Segment of the Copperbelly Water Snake (Nerodia Erythrogaster Neglecta) Recovery Plan

U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Northern Population Segment of the Copperbelly Water Snake (Nerodia erythrogaster neglecta) Recovery Plan December 2008 Department of the Interior U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Midwest Region Fort Snelling, MN Cover graphic The drawing of Nerodia erythrogaster is reproduced with permission of the authors from the book, North American Watersnakes: A Natural History, by J. Whitfield Gibbons and Michael E. Dorcas, published by the University of Oklahoma Press (2004). Drawing by Peri Mason, Savannah River Ecology Laboratory. DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions which are believed to be required to recover and/or conserve listed species. Plans are published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), sometimes prepared with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, state agencies, and others. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views or the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the Service. They represent the official position of the Service only after they have been signed by the Regional Director. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery actions. LITERATURE CITATION SHOULD READ AS FOLLOWS: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2008. Northern Population Segment of the Copperbelly Water Snake (Nerodia erythrogaster neglecta) Recovery Plan. Fort Snelling, Minnesota. ix + 79 pp. ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS PLAN CAN BE OBTAINED FROM: U.S. -

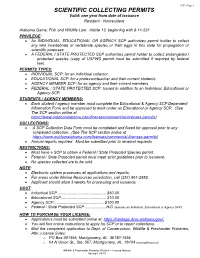

SCIENTIFIC COLLECTING PERMITS Valid: One Year from Date of Issuance Resident - Nonresident

SCP – Page 1 SCIENTIFIC COLLECTING PERMITS Valid: one year from date of issuance Resident - Nonresident Alabama Game, Fish and Wildlife Law; Article 12; beginning with 9-11-231 PRIVILEGE: • An INDIVIDUAL, EDUCATIONAL OR AGENCY SCP authorizes permit holder to collect any wild invertebrate or vertebrate species or their eggs in this state for propagation or scientific purposes. • A FEDERAL / STATE PROTECTED SCP authorizes permit holder to collect endangered / protected species (copy of USFWS permit must be submitted if required by federal law). PERMITS TYPES: • INDIVIDUAL SCP: for an individual collector. • EDUCATIONAL SCP: for a professor/teacher and their current students. • AGENCY MEMBER SCP: for an agency and their current members. • FEDERAL / STATE PROTECTED SCP: Issued in addition to an Individual, Educational or Agency SCP. STUDENTS / AGENCY MEMBERS: • Each student / agency member must complete the Educational & Agency SCP Dependent Information Form and be approved to work under an Educational or Agency SCP. (See The SCP section online at https://www.outdooralabama.com/licenses/commercial-licenses-permits) COLLECTIONS: • A SCP Collection Data Form must be completed and faxed for approval prior to any scheduled collection. (See The SCP section online at https://www.outdooralabama.com/licenses/commercial-licenses-permits) • Annual reports required. Must be submitted prior to renewal requests. RESTRICTIONS: • Must have a SCP to obtain a Federal / State Protected Species permit. • Federal / State Protected permit must meet strict guidelines prior to issuance. • No species collected are to be sold. NOTE: • Electronic system processes all applications and reports. • For areas under Marine Resources jurisdiction, call (251) 861-2882. • Applicant should allow 3 weeks for processing and issuance.