Australia and the Olympic Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

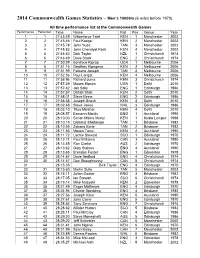

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men's

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men’s 10000m (6 miles before 1970) All time performance list at the Commonwealth Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 27:45.39 Wilberforce Talel KEN 1 Manchester 2002 2 2 27:45.46 Paul Kosgei KEN 2 Manchester 2002 3 3 27:45.78 John Yuda TAN 3 Manchester 2002 4 4 27:45.83 John Cheruiyot Korir KEN 4 Manchester 2002 5 5 27:46.40 Dick Taylor NZL 1 Christchurch 1974 6 6 27:48.49 Dave Black ENG 2 Christchurch 1974 7 7 27:50.99 Boniface Kiprop UGA 1 Melbourne 2006 8 8 27:51.16 Geoffrey Kipngeno KEN 2 Melbourne 2006 9 9 27:51.99 Fabiano Joseph TAN 3 Melbourne 2006 10 10 27:52.36 Paul Langat KEN 4 Melbourne 2006 11 11 27:56.96 Richard Juma KEN 3 Christchurch 1974 12 12 27:57.39 Moses Kipsiro UGA 1 Delhi 2010 13 13 27:57.42 Jon Solly ENG 1 Edinburgh 1986 14 14 27:57.57 Daniel Salel KEN 2 Delhi 2010 15 15 27:58.01 Steve Binns ENG 2 Edinburgh 1986 16 16 27:58.58 Joseph Birech KEN 3 Delhi 2010 17 17 28:02.48 Steve Jones WAL 3 Edinburgh 1986 18 18 28:03.10 Titus Mbishei KEN 4 Delhi 2010 19 19 28:08.57 Eamonn Martin ENG 1 Auckland 1990 20 20 28:10.00 Simon Maina Munyi KEN 1 Kuala Lumpur 1998 21 21 28:10.15 Gidamis Shahanga TAN 1 Brisbane 1982 22 22 28:10.55 Zakaria Barie TAN 2 Brisbane 1982 23 23 28:11.56 Moses Tanui KEN 2 Auckland 1990 24 24 28:11.72 Lachie Stewart SCO 1 Edinburgh 1970 25 25 28:12.71 Paul Williams CAN 3 Auckland 1990 25 26 28:13.45 Ron Clarke AUS 2 Edinburgh 1970 27 27 28:13.62 Gary Staines ENG 4 Auckland 1990 28 28 28:13.65 Brendan Foster ENG 1 Edmonton 1978 29 29 28:14.67 -

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics–Men's 5000M (3 Mi Before

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics –Men’s 5000m (3 mi before 1970) by K Ken Nakamura All time performance list at the Commonwealth Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 12:56.41 Augustine Choge KEN 1 Melbourne 2006 2 2 12:58.19 Craig Mottram AUS 2 Melbourne 2006 3 3 13:05.30 Benjamin Limo KEN 3 Melbourne 2006 4 4 13:05.89 Joseph Ebuya KEN 4 Melbourne 2006 5 5 13:12.76 Fabian Joseph TAN 5 Melbourne 2006 6 6 13:13.51 Sammy Kipketer KEN 1 Manchester 2002 7 13:13.57 Benjamin Limo 2 Manchester 2002 8 7 13:14.3 Ben Jipcho KEN 1 Christchurch 1974 9 8 13.14.6 Brendan Foster GBR 2 Christchurch 1974 10 9 13:18.02 Willy Kiptoo Kirui KEN 3 Manchester 2002 11 10 13:19.43 John Mayock ENG 4 Manchester 2002 12 11 13:19.45 Sam Haughian ENG 5 Manchester 2002 13 12 13:22.57 Daniel Komen KEN 1 Kuala Lumpur 1998 14 13 13:22.85 Ian Stewart SCO 1 Edinburgh 1970 15 14 13:23.00 Rob Denmark ENG 1 Victoria 1994 16 15 13:23.04 Henry Rono KEN 1 Edmonton 1978 17 16 13:23.20 Phillimon Hanneck ZIM 2 Victoria 1994 18 17 13:23.34 Ian McCafferty SCO 2 Edinburgh 1970 19 18 13:23.52 Dave Black ENG 3 Christchurch 1974 20 19 13:23.54 John Nuttall ENG 3 Victoria 1994 21 20 13:23.96 Jon Brown ENG 4 Victoria 1994 22 21 13:24.03 Damian Chopa TAN 6 Melbourne 2006 23 22 13:24.07 Philip Mosima KEN 5 Victoria 1994 24 23 13:24.11 Steve Ovett ENG 1 Edinburgh 1986 25 24 13:24.86 Andrew Lloyd AUS 1 Auckland 1990 26 25 13:24.94 John Ngugi KEN 2 Auckland 1990 27 26 13:25.06 Moses Kipsiro UGA 7 Melbourne 2006 28 13:25.21 Craig Mottram 6 Manchester 2002 29 27 13:25.63 -

1 Ron Clarke, Runner 1937- I Had the Great Honour of Carrying the Torch

1 PEOPLE WHO CHANGED MELBOURNE Schools City Tour of Melbourne: www.melbournewalks.com.au/city-schools-tour ; www.melbournewalks.com; [email protected] ; Copyright Melbourne Walks © Peter Lalor, Rebel (1827-1889) As Eureka stockade leader in December 1854 I took the oath of the rebel miners: ‘We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other to defend our rights and liberties’. I lost my arm in that battle yet later became the only outlaw ever elected to parliament! On 24 Nov 1857 all men received the right to vote. Our Southern Cross flag is now the Australian flag. Down with tyranny! John Batman, Founder of Colonial Melbourne (1801 –1839) I was a Tasmania sheep farmer when I led an expedition to sign a ‘treaty’ with Aboriginal ‘chiefs’ in 1835 to found the settlement of Melbourne and the colony of Victoria. I captured bushranger Mathew Brady and married a runaway convict Eliza Callaghan. We had seven children in all. At Melbourne’s first land sale in 1837. I bought the Young and Jackson Hotel site opposite Flinders Street Station to build a home for my children. It became a schoolhouse in 1839 and today a famous pub. See Chloe upstairs! Ron Clarke, Runner 1937- I had the great honour of carrying the torch into the stadium in the Melbourne Olympic Games in 1956. I was also the first man to run three miles in under 13 minutes. They said I was fastest man on the planet when I broke 17 world records and 25 Australian records in 1965. -

Il Ritorno E Tutto Il Resto

NUMERO 173 in edizione telematica 21 MARZO 2012 DIRETTORE: GIORS ONETO e.mail: [email protected] IL RITORNO E TUTTO IL RESTO Alex Schwazer, con il primato italiano e la condurlo al primato italiano all’aperto di Per un sol posto Marzia Caravelli, migliore prestazione mondiale nei 20km di Fabrizio Donato, metri 17,60 nel 2000 a trentenne di Pordenone ha mancato la Lugano, 1h17”30 nel giorno di San Milano. Abate, 26enne di Alassio, ha le finale nei 60 hs con 8”12. Promettente Giuseppe Lavoratore, ha fugato i dubbi misure antropometriche giuste (1,90 per 78 esordio con semifinale di Veronica Borsi residui sulla sua condizione agonistica ed kg) per aspirare al primato italiano dei 110 8”18 Dominatrice la superba specialista è, con Antonietta di Martino nell’alto, lo hs. ( dopo il suo primato nei 60 hs con australiana Sally Paersson 7”73. A rendere squarcio di azzurro in un cielo plumbeo 7”57). L’ostacolista ligure è allenato dal più consistente il carnet del settore per la nostra atletica. professore dell’Educazione Fisica di una ostacoli, il piazzamento in semifinale di Il 24 prossimo in Slovacchia l’allievo di volta, Pietro Astengo, che ha usufruito Paolo Dal Molin, camerunense acquisito. Michele Didoni – che uno Spiridon fa ci della meritata quiescenza dopo Anche il quattrocentometrista di Rieti, aveva dato la primizia della super forma di l’insegnamento nella Scuola, ed ora si Lorenzo Valentino, ventenne, ha esordito Alex – porterà a casa “ad anche basse” il diletta. A quanto leggiamo nel conquistando una fortunosa semifinale con minimo olimpico nei 50km. -

Fair Play 1964-2005 INGLESE

Fair Play Trophies et Diplomas awarded by IFPC from 1964 to 2005 Winners Publication edited in agreement with the International Committee for Fair Play Panathlon International Villa Porticciolo – Via Maggio, 6 16035 Rapallo - Italie www.panathlon.net e-mail: [email protected] project and cultural coordination International Committee for Fair Play Panathlon International works coordinators Jean Durry Siropietro Quaroni coordination assistants Nicoletta Bena Emanuela Chiappe page layout and printing: Azienda Grafica Busco - Rapallo 2 Contents Jeno Kamuti 5 The "Fair Play", its sense and its winners Enrico Prandi 8 “Angel or Demon? The choise of Fair Play” Definition and History 11 of the International Committee for Fair Play Antonio Spallino 25 Panathlon International and the promotion of Fair Play Fair Play World Trophies Trophies and Diplomas 33 awarded by International Committee for Fair play from the origin Letters of congratulations 141 Nations legend 150 Disciplines section 155 Alphabethical index 168 3 Jeno Kamuti President of the International Fair Play Committee The “Fair Play”, its sense and its winners Nowadays, at the beginning of the XXIst century, sport has finally earned a worthy place in the hier - archy of society. It has become common wisdom that sport is not only an activity assuring physical well-being, it is not only a phenomenon carrying and reinforcing human values while being part of general culture, but that it is also a tool in the process of education, teaching and growing up to be an upright individ - ual. Up until now, we have mostly contented our - selves with saying that sport is a mirror of human activities in society. -

Newsletter 2020

NEWSLETTER 2020 POOVAMMA ENJOYING TRANSITION TO SENIOR STATESMAN ROLE IN DYNAMIC RELAY SQUAD M R Poovamma has travelled a long way from being the baby of the Indian athletics contingent in the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing to being the elder FEATURED ATHLETE statesman in the 2018 Asian Games in Jakarta. She has experienced the transition, slipping into the new role MR Poovamma (Photo: 2014 Incheon Asian Games @Getty) effortlessly and enjoying the process, too. “It has been a different experience over the past couple of years. Till 2017, I was part of a squad that had runners who were either as old as me or a couple of years older. But now, most of the girls in the team are six or seven years younger than I am,” she says from Patiala. “On the track they see me as a competitor but outside, they look up to me like a member of their family.” The lockdown, forced by the Covid-19 outbreak, and the aftermath have given her the opportunity to don the leadership mantle. “For a couple of months, I managed the workout of the other girls. I enjoyed the role assigned to me,” says the 30-year-old. “We were able to maintain our fitness even during lockdown.” Poovamma reveals that the women’s relay squad trained in the lawn in the hostel premises. “It was a change off the track. We hung out together. It was not like it was a punishment, being forced to stay away from the track and the gym. Our coaches and Athletics Federation of India President Adille (Sumariwalla) sir and (Dr. -

The Gap Between the Management and Success of Elite Middle and Long Distance Runners in Kenya

African Journalfor Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance (AJPHERD) Volume 21(2), June 2015, pp. 586-595. The gap between the management and success of elite middle and long distance runners in Kenya 1 2 LEWIS R. KANYIBA , ANDANJE MWISUKHA AND VINCENT O. ONYWERA2 JDepartment of Health and Physical Education, Bethel University, 325 Cherry Avenue, McKenzie, Tennessee 38201, USA. E-mail: [email protected]@gmail.com 2Department of Recreation Management and Exercise Science, Kenyatta University, P.G. Box 43844-00100 Nairobi, Kenya (Received: 11February 2015; Revision Accepted: 17 May 2015) Abstract Kenya has been very successful at middle and long distance races in international competitions for the last five decades. However, Kenyan world record beaters have denounced the motherland flag by switching nationality, sought training in alien bases under foreign managers, been living under deplorable conditions after athletic career, or they have been the victim of neglect-induced death at a prime career age. There is extensive research available on the success of Kenyan athletes, but no study to the knowledge of the researchers has linked the management of Kenyan athletes to that success. As a foundation for further research, the current exploratory study was designed to determine whether elite athletes, their coaches, and administrative officials (Athletics Kenya [AK] officials) differed on the effectiveness of the sampled managerial practices (personnel, equipment/facilities, motivation, patriotism, team selection, and training programs) in facilitating the success of Kenyan elite runners. The study further details the effect of nationality change and the role of foreign managers towards the success of Kenyans in distance running. -

Agenda Item No 3 Bristol City Council Full Council 5 July

AGENDA ITEM NO 3 BRISTOL CITY COUNCIL FULL COUNCIL 5 JULY 2012 Report of: Title: Proposal to Confer the Honour of the Freedom of the City on Kipchoge Keino, Chairman of the National Olympic Committee of Kenya, and Member of the International Olympic Committee. Ward: Citywide Report presented by: The Lord Mayor of Bristol Contact Telephone Number: Lord Mayor's Office - 0117 903 1450 RECOMMENDATION (i) That the Freedom of the City of Bristol be conferred upon Kipchoge Keino, Chairman of the National Olympic Committee of Kenya to mark the presence in the city of the Kenyan Olympic and Paralympic teams who are staging their training camps here prior to the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games (ii) That his name be placed on the Roll of Honorary Freeman of the City; and (iii) That the foregoing be engrossed, sealed with the Common Corporate Seal and presented to Kipchoge (Kip) Keino at an appropriate occasion. Summary To propose the granting of the Freedom of the City to Kipchoge Keino, Chairman of the National Olympic Committee of Kenya. - 1 - Policy 1. The proposal is made in accordance with the provision of the Local Government Act 1972. Consultation 2. The City Council's Party Group Leaders. Background and Assessment 3. The Citation attached to this report outlines the distinguished and eminent service rendered by Kipchoge Keino and his influence as a 'friend' of the city. 4. Legal and Resource Implications Legal None Financial None Revenue The estimated cost of recognising the granting of the Freedom of the City would be less that £200 and would be met within existing budgets. -

Test Booklet Subject: READ, Grade: 09 1.10 9Th Grade English Midterm– Reading Skills a - BH Block: 101BHUE1A

Test Booklet Subject: READ, Grade: 09 1.10 9th Grade English Midterm– Reading Skills A - BH Block: 101BHUE1A Student name: Author: Deborah Stern School: Freire Charter School Administer Date: Wednesday January 13, 2010 Test Booklet for READ:09, 1.10 9th Grade English Midterm– Reading Skills A - BH Instructions for Test Administrator Page i ADMIN INSTRUCTIONS, DO NOT COPY Test Booklet for READ:09, 1.10 9th Grade English Midterm– Reading Skills A - BH Read the passage, “The Fosbury Flop," and answer the following question(s). The Fosbury Flop Rich Wallace Dick Fosbury raced across the infield, planted his foot, and Coach Wagner joked later. leaped into the air, straining with every muscle to propel himself over the high-jump bar. But as he soared into the Within a year, Fosbury’s unique style of jumping had been air, his knee hit the bar, and it fell to the ground with a dubbed “The Fosbury Flop," and his string of successes clang. brought great excitement to the sport of track and field. He cleared 7 feet for the first time early in the 1968 season, The tall, lean high-school kid from Medford, Oregon, sat then won the league championship and the National up in the pit and looked at the bar in frustration. There had Collegiate Athletic Association title. That summer he to be a better way to do this. competed in the trials to select the United States team for the Summer Olympic Games. He soared over the bar at 7 Fosbury had been trying to succeed with the feet, 3 inches to qualify for the team. -

Our Part in Four-Minute Mile History

Our part in four-minute mile history Bruce McAvaney addressed a dinner in Melbourne recently, to commemorate Australian John Landy's first sub-four-minute mile and world record, run 50 years ago, six weeks after Roger Bannister first went under four. This is the transcript of his speech. "Here is the result of event No.9, the one mile: No. 41, R G Bannister, of the Amateur Athletic Association and formerly of Exeter and Merton Colleges, with a time that is a new meeting and track record, and which, subject to ratification, with be a new English native, British National, British all-comers, European, British Empire and World Record. The time is 3…." That's arguably the most famous cue, let alone understated announcement in athletics history…3 Minutes, 59.4 seconds! He was a formidable character, the announcer. Norris McWhirter died earlier this year, unfortunately just before the 50th anniversary of the first sub-four minute mile. McWhirter apparently had rehearsed assiduously the night before, in his bath, and it was through him that the BBC, the newsreel camera and most of the print media were present that day. McWhirter, and his twin Ross, who was gunned down in 1975 by the IRA, were joint founders and editors of the Guinness Book of Records. McWhirter had a sense of humour. Here in Melbourne at the 1956 Olympics, he told the story of a middle-aged Australian woman who, observing distressing scenes at the finish of the marathon exclaimed, "Cripes, how many qualify for the final?"… Back to Bannister, and the race: is it the sport's finest achievement? How does the 3.59.4 stack up with other athletic landmarks? Classics such as our own Ron Clarke's 27:39.4 in Oslo in 1965, a 35 second improvement on the previous mark. -

Wolscript.Pdf

Without Limits (Warner Brothers, 1998) Running time: 1 hour, 58 minutes Selected Film Credits Produced by Tom Cruise and Paula Wagner Directed by Robert Towne Executive Producers – Jonathan Sanger and Kenny Moore Written by Robert Towne and Kenny Moore Track Consultants – Frank Shorter, John Gillespie, Steve Bence Special Consultants – Bill and Barbara Bowerman, Jim Jaqua, Mary Marckx, Dave Frohnmayer Original music composed and conducted by Randy Miller Partial Cast of Characters Steve Prefontaine Billy Crudup Olympic Trials Bill Bowerman Donald Sutherland George Young Garth Granholm Walt McClure Greg Foote Bill Dellinger Dean Norris Munich Olympics Elfriede Prefontaine Lisa Banes TV Director William Friedkin Kenny Moore Billy Burke Charlie Jones Himself Roscoe Devine Matthew Lillard Fred Long Frank Shorter Mary Marckx Monica Potter BBC Commentator David Coleman Molly Cox Karen Elliott Prefontaine (age 6) Jamie Schwering Bob Peters William Mapother Bully Coleman Dow Barbara Bowerman Judith Ivey German Guard John Roemer Mac Wilkins Adam Setliff Russ Francis Nicholas Oleson Lasse Viren Pat Porter Hayward Field Announcer Wendy Ray Mohammed Gammoudi Steve Ave Starter Wade Bell Dave Bedford Jonathan Pritchard Don Kardong Gabriel Olds Emiel Puttemans Tom Ansberry Turn Judge Edwin L. Coleman II Harold Norpoth Sol Alexis Sallos Coed #1 Katharine Towne Juha Vaatinen Thomas DeBacker Coed #2 Cassandra A. Coogan Ian Stewart Ashley Johnson Coed #3 Amy Erenberger Javier Alvarez Brad Hudson Frank Eisenberg Todd D. Lewis NCAA Championships Per Halle Tove Christensen Iowa’s Finest Amy Jo Johnson Nikolay Sviridov Chris Caldwell Ian McCafferty Paul Vincent Helsinki Frank Shorter Jeremy Cisto Restoration Meet & Party Finnish Track Official #1 Ryan S. -

Willie Davenport Clinic

Willie Davenport Olympian Track and Field Clinic February 8, 2014 James Logan High School 8:00 a.m. — 5:00 p.m. Cost: $20 per person/ $350 per Team 2014 Clinic Dedicated to Coach Berny Wagner Berny Wagner with Dick Fosbury 2014 Clinic Speakers John Carlos Kenny Harrison Mac Wilkins Michael Powell Karin Smith Eddie Hart technology Andre Phillips Crazy George and many more! For more information please call Coach Lee Webb at 510-304-7172 or email at [email protected] Website: http://logantrackandfield.com/ Willie Davenport Olympian Track and Field Clinic James Logan High School Contact Lee Webb-510-304-7172 February 8, 2014 8:00-9:00 Registration 9:00-4:00 Events website:logantrackandfield.com Individuals $20.00 Youth $10.00-8th grade and under Team $350.00 Team of 50+ $500.00 Learn-by doing clinic for all ages Special Guests and Clincians Kenny Harrison-American Record Holder and Olympic Champion Triple Jump Stephanie Brown-Trafton-2008 Olympic Champion Discus Reynaldo Brown-2 TimeOlympian High Jump Mike Powell-World Record Holder Long Jump Mac Wilkins-Former World Record Holder Discus 7 Time World Record Holder Eddie Hart-World Fastest Human 1972 Dick Fosbury-High Jump Olympic Champion Karin Smith-5 Time Olympian in the Javelin Marcel Hetu-Olympic Coach Michael Ripley-LSU Trainer Olympic Trainer Dave Schrock-Olympic Coach Crazy George-World Greatest Cheerleader Mike Lousiana-Discus NCCA Champ Andre Phillips-Gold Medalist 400 Hurdles Ken Grace-Olympic Coach John Carlos-1968 Olympian 200 Meters Tyrus Jefferson-27ʼ2 Long Jumper More Clinicians: