Status of 'Fork-Tailed Swift' Apus Pacificus Complex in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Preprint

Does evolution of plumage patterns and of migratory behaviour in Apodini swifts (Aves: Apodiformes) follow distributional range shifts? Dieter Thomas Tietze, Martin Päckert, Michael Wink The Apodini swifts in the Old World serve as an example for a recent radiation on an intercontinental scale on the one hand. On the other hand they provide a model for the interplay of trait and distributional range evolution with speciation, extinction and trait s t transition rates on a low taxonomic level (23 extant taxa). Swifts are well adapted to a life n i mostly in the air and to long-distance movements. Their overall colouration is dull, but r P lighter feather patches of chin and rump stand out as visual signals. Only few Apodini taxa e r breed outside the tropics; they are the only species in the study group that migrate long P distances to wintering grounds in the tropics and subtropics. We reconstructed a dated molecular phylogeny including all species, numerous outgroups and fossil constraints. Several methods were used for historical biogeography and two models for the study of trait evolution. We finally correlated trait expression with geographic status. The differentiation of the Apodini took place in less than 9 Ma. Their ancestral range most likely comprised large parts of the Old-World tropics, although the majority of extant taxa breed in the Afrotropic and the closest relatives occur in the Indomalayan. The expression of all three investigated traits increased speciation rates and the traits were more likely lost than gained. Chin patches are found in almost all species, so that no association with phylogeny or range could be found. -

Notas Breves FOOD HABITS of the ALPINE SWIFT on TWO

Ardeola 56(2), 2009, 259-269 Notas Breves FOOD HABITS OF THE ALPINE SWIFT ON TWO CONTINENTS: INTRA- AND INTERSPECIFIC COMPARISONS DIETA DEL VENCEJO REAL EN DOS CONTINENTES: ANÁLISIS COMPARATIVO INTRA E INTERESPECÍFICO Charles T. COLLINS* 1, José L. TELLA** and Brian D. COLAHAN*** SUMMARY.—The prey brought by alpine swifts Tachymarptis melba to their chicks in Switzerland, Spain and South Africa included a wide variety of arthropods, principally insects but also spiders. Insects com- prised 10 orders and 79 families, the Homoptera, Diptera and Hymenoptera being the most often con- sumed. The assessment of geographical variation in the diet was complicated by the great variability among the individual supplies of prey. Prey size varied between 1.3 and 29.6 mm, differing significantly in the median prey size of the three populations (5.12 - 8.81 mm) according to the intraspecific variation in size of alpine swifts. In an interspecific comparison, prey size correlated positively with body size in seven species of swifts. RESUMEN.—Las presas aportadas por vencejos reales Tachymarptis melba a sus pollos en Suiza, Es- paña y Sudáfrica incluyeron una amplia variedad de artrópodos, principalmente insectos pero también arañas. Entre los insectos, fueron identificados 10 órdenes y 79 familias, siendo Homoptera, Diptera e Hymenoptera los más consumidos. Las variaciones geográficas en la dieta se vieron ensombrecidas por una gran variabilidad entre los aportes individuales de presas. El tamaño de presa varió entre 1.3 y 29.6 mm, oscilando las medianas para cada población entre 5,12 y 8,81 mm. Los vencejos reales mostraron di- ferencias significativas en el tamaño de sus presas correspondiendo con su variación intraespecífica en tamaño. -

Dieter Thomas Tietze Editor How They Arise, Modify and Vanish

Fascinating Life Sciences Dieter Thomas Tietze Editor Bird Species How They Arise, Modify and Vanish Fascinating Life Sciences This interdisciplinary series brings together the most essential and captivating topics in the life sciences. They range from the plant sciences to zoology, from the microbiome to macrobiome, and from basic biology to biotechnology. The series not only highlights fascinating research; it also discusses major challenges associated with the life sciences and related disciplines and outlines future research directions. Individual volumes provide in-depth information, are richly illustrated with photographs, illustrations, and maps, and feature suggestions for further reading or glossaries where appropriate. Interested researchers in all areas of the life sciences, as well as biology enthusiasts, will find the series’ interdisciplinary focus and highly readable volumes especially appealing. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/15408 Dieter Thomas Tietze Editor Bird Species How They Arise, Modify and Vanish Editor Dieter Thomas Tietze Natural History Museum Basel Basel, Switzerland ISSN 2509-6745 ISSN 2509-6753 (electronic) Fascinating Life Sciences ISBN 978-3-319-91688-0 ISBN 978-3-319-91689-7 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91689-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018948152 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

CBD First National Report

FIRST NATIONAL REPORT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA TO THE UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION ON BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY July 2010 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................... 3 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................... 4 2. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Geographic Profile .......................................................................................... 5 2.2 Climate Profile ...................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Population Profile ................................................................................................. 7 2.4 Economic Profile .................................................................................................. 7 3 THE BIODIVERSITY OF SERBIA .............................................................................. 8 3.1 Overview......................................................................................................... 8 3.2 Ecosystem and Habitat Diversity .................................................................... 8 3.3 Species Diversity ............................................................................................ 9 3.4 Genetic Diversity ............................................................................................. 9 3.5 Protected Areas .............................................................................................10 -

Crustacea, Notostraca) from Iran

Journal of Biological Research -Thessaloniki 19 : 75 – 79 , 20 13 J. Biol. Res. -Thessalon. is available online at http://www.jbr.gr Indexed in: Wos (Web of science, IsI thomson), sCOPUs, CAs (Chemical Abstracts service) and dOAj (directory of Open Access journals) — Short CommuniCation — on the occurrence of Lepidurus apus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Crustacea, notostraca) from iran Behroz AtAshBAr 1,2 *, N aser Agh 2, L ynda BeLAdjAL 1 and johan MerteNs 1 1 Department of Biology , Faculty of Science , Ghent University , K.L. Ledeganckstraat 35 , 9000 Gent , Belgium 2 Department of Biology and Aquaculture , Artemia and Aquatic Animals Research Institute , Urmia University , Urmia-57153 , Iran received: 16 November 2011 Accepted after revision: 18 july 2012 the occurrence of Lepidurus apus in Iran is reported for the first time. this species was found in Aigher goli located in the mountains area, east Azerbaijan province (North east, Iran). details on biogeography, ecology and morphology of this species are provided. Key words: Lepidurus apus , Aigher goli, east Azerbaijan, Iran. INtrOdUCtION their world-wide distribution is due to their anti qu - ity, but possibly also to their passive transport: geo - Notostracan records date back to the Carboniferous graphical barriers are more effective for non-passive - and possibly up to the devonian period (Wallossek, ly distributed animals. From an ecological point of 1993, 1995; Kelber, 1998). In fact, there are Upper view, notostracans, like most branchiopods, are re - triassic Triops fossils from germany -

Biodiversity Profile of Afghanistan

NEPA Biodiversity Profile of Afghanistan An Output of the National Capacity Needs Self-Assessment for Global Environment Management (NCSA) for Afghanistan June 2008 United Nations Environment Programme Post-Conflict and Disaster Management Branch First published in Kabul in 2008 by the United Nations Environment Programme. Copyright © 2008, United Nations Environment Programme. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNEP would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United Nations Environment Programme. United Nations Environment Programme Darulaman Kabul, Afghanistan Tel: +93 (0)799 382 571 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.unep.org DISCLAIMER The contents of this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of UNEP, or contributory organizations. The designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP or contributory organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Unless otherwise credited, all the photos in this publication have been taken by the UNEP staff. Design and Layout: Rachel Dolores -

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-B 17 January 2018

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-B 17 January 2018 No. Page Title 01 02 Split Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus into four species 02 05 Restore Canada Jay as the English name of Perisoreus canadensis 03 13 Recognize two genera in Stercorariidae 04 15 Split Red-eyed Vireo (Vireo olivaceus) into two species 05 19 Split Pseudobulweria from Pterodroma 06 25 Add Tadorna tadorna (Common Shelduck) to the Checklist 07 27 Add three species to the U.S. list 08 29 Change the English names of the two species of Gallinula that occur in our area 09 32 Change the English name of Leistes militaris to Red-breasted Meadowlark 10 35 Revise generic assignments of woodpeckers of the genus Picoides 11 39 Split the storm-petrels (Hydrobatidae) into two families 1 2018-B-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 280 Split Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus into four species Effect on NACC: This proposal would change the species circumscription of Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus by splitting it into four species. The form that occurs in the NACC area is nominate pacificus, so the current species account would remain unchanged except for the distributional statement and notes. Background: The Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus was until recently (e.g., Chantler 1999, 2000) considered to consist of four subspecies: pacificus, kanoi, cooki, and leuconyx. Nominate pacificus is highly migratory, breeding from Siberia south to northern China and Japan, and wintering in Australia, Indonesia, and Malaysia. The other subspecies are either residents or short distance migrants: kanoi, which breeds from Taiwan west to SE Tibet and appears to winter as far south as southeast Asia. -

ORL 5.1 Non-Passerines Final Draft01a.Xlsx

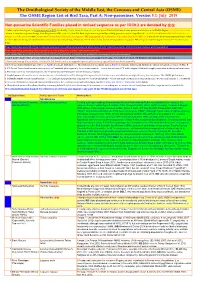

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part A: Non-passerines. Version 5.1: July 2019 Non-passerine Scientific Families placed in revised sequence as per IOC9.2 are denoted by ֍֍ A fuller explanation is given in Explanation of the ORL, but briefly, Bright green shading of a row (eg Syrian Ostrich) indicates former presence of a taxon in the OSME Region. Light gold shading in column A indicates sequence change from the previous ORL issue. For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates added information since the previous ORL version or the Conservation Threat Status (Critically Endangered = CE, Endangered = E, Vulnerable = V and Data Deficient = DD only). Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative convenience and may change. Please do not cite them in any formal correspondence or papers. NB: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text indicate recent or data-driven major conservation concerns. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. English names shaded thus are taxa on BirdLife Tracking Database, http://seabirdtracking.org/mapper/index.php. Nos tracked are small. NB BirdLife still lump many seabird taxa. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. -

An Overview of Apus Apus-And Apus Apus Pekinensis Swifts Have Been Around for About 50 Million Years!

An overview of Apus apus-and Apus apus pekinensis Swifts have been around for about 50 million years! • Eocypselus rowei. • Found in Wyoming. • 12 centimetres from head to tail. • Around 50 million years old • Evolutionary precursor to swifts and hummingbirds. • Scaniacypselus fossil in Senckenberg Museum Frankfurt - Scanish Swift – 49 million years old. Photo Ulrich Tigges. • The story here is more about avian classification rather than details of swift evolution. • Reptiles to birds to modern birds! • Around 100 species of swift. Apus apus and Apus apus pekinensis Very widespread distribution Apus apus ‘HABITAT’ IS “AIR” • IT’S ALL ABOUT FLIGHT! • Look at the length of the wings- • Unlike most birds - e.g. sparrowhawk in woodland - IT’S NOT LIMITED BY SPECIFIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS! • aerial plankton feeder • A bird of the air! • The Non Stop bird! Adapted at a molecular level. A powerful and finely tuned engine • 100% Type 1 muscle fibres – packed with mitochondria • Energy source is fat – more efficient than high octane fuel! • Same as Humming birds which are also Type 1 • Swifts like Jets refuel in mid air! Non Stop life in the air brings some unavoidable consequences! • Swallow can perch-passerine. • Feeds its fledged young – swift does not. • Builds its nest with mud. Swifts in cavity • Swallow preens when perched. • Can get Calcium and minerals from the ground. • Swallow roosts. Swift sleeps on wing. • Convergent evolution – species are not related. • Swift Torpor. Swallow not. • Totally different ball game. • Very different life strategies! • Researches need to be aware of this! • Many of the characteristics of the swift are the inevitable result of its evolutionary path. -

Red List of Bangladesh 2015

Red List of Bangladesh Volume 1: Summary Chief National Technical Expert Mohammad Ali Reza Khan Technical Coordinator Mohammad Shahad Mahabub Chowdhury IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature Bangladesh Country Office 2015 i The designation of geographical entitles in this book and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature concerning the legal status of any country, territory, administration, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The biodiversity database and views expressed in this publication are not necessarily reflect those of IUCN, Bangladesh Forest Department and The World Bank. This publication has been made possible because of the funding received from The World Bank through Bangladesh Forest Department to implement the subproject entitled ‘Updating Species Red List of Bangladesh’ under the ‘Strengthening Regional Cooperation for Wildlife Protection (SRCWP)’ Project. Published by: IUCN Bangladesh Country Office Copyright: © 2015 Bangladesh Forest Department and IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holders, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holders. Citation: Of this volume IUCN Bangladesh. 2015. Red List of Bangladesh Volume 1: Summary. IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Bangladesh Country Office, Dhaka, Bangladesh, pp. xvi+122. ISBN: 978-984-34-0733-7 Publication Assistant: Sheikh Asaduzzaman Design and Printed by: Progressive Printers Pvt. -

Appendix 12.1 Literature Review

E xpansion of Hong Kong International Airport into a Three-Runway System Environmental Impact Assessment Report Appendix 12.1 Literature Review Literature Review 1 Background 1.1 The purpose of the literature review is to identify existing information on the terrestrial habitats and species present within the study area in order to identify any information gaps and take into account such information gaps in the design of terrestrial ecological surveys. A series of materials, including relevant EIA studies, academic research papers, results of ecological research or monitoring done by government authorities such as the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department (AFCD) or non-government organisations, have been reviewed to gather relevant data on the terrestrial flora and fauna species present in the study area. 1.2 Relevant EIA reports and studies that provide a considerable amount of information on the terrestrial ecology of North Lantau from Sham Wat to Tai Ho Wan and Chek Lap Kok have been reviewed. The EIA reports and studies that have been reviewed include: Hong Kong - Zhuhai - Macao Bridge: Hong Kong Boundary Crossing Facilities and Hong Kong Link Road Final 9 Months Ecological Baseline Survey (Mouchel, 2004); Hong Kong - Zhuhai - Macao Bridge: Hong Kong Link Road Verification Survey of Ecological Baseline Final Report (Asia Ecological Consultants Ltd, 2009); Tuen Mun - Chek Lap Kok Link (TM-CLKL) - Investigation Final EIA Report (AECOM, 2009); Hong Kong - Zhuhai - Macao Bridge: Hong Kong Boundary Crossing Facilities (HKBCF) -

Recent Bird Records from Fogo, Cape Verde Islands Rubén Baronea and Jens Heringb

Recent bird records from Fogo, Cape Verde Islands Rubén Baronea and Jens Heringb Observations récentes de Fogo, Îles du Cap-Vert. Des données sont présentées concernant 12 espèces d’oiseaux observées à Fogo, Îles du Cap-Vert, parmi lesquelles deux premières mentions pour l’île (Chevalier gambette Tringa totanus et Hirondelle de fenêtre Delichon urbicum), les premières données de nidification du Martinet du Cap-Vert Apus alexandri et les premières observations fiables du Phaéton à bec rouge Phaethon aethereus indiquant la nidification probable de celui-ci. Des informations sont également présentées sur d’autres taxons mal connus à Fogo, tels que certaines espèces pélagiques et l’Effraie des clochers Tyto alba detorta. Summary. We present data on 12 bird species observed on Fogo, Cape Verde Islands, among them two first records for the island (Common Redshank Tringa totanus and Common House Martin Delichon urbicum), the first breeding records of Cape Verde Swift Apus alexandri and the first reliable observations of Red-billed Tropicbird Phaethon aethereus indicating probable breeding. Information on other taxa poorly known on Fogo, such as some pelagic seabirds and Barn Owl Tyto alba detorta, is also given. ogo, one of the Cape Verde Islands, is situated reported previously, and some others for which F in the leeward group (‘Ilhas do Sotavento’), there are only a limited number of observations. c.724 km from the African continent. With Local information on breeding birds was mainly a surface area of 478 km2, the highest peak collected by RB. Dates of our visits are as follows: (Pico Novo) reaches 2,829 m (Michell-Thomé 18–21 October 2004 (JH & H.