Seeing Stars: Matthew Effects and Status Bias in Major League Baseball Umpiring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

N Bitter About Export Limits

MANCHESTER, CONN., MONDAY, JULY 16, 1973 — VOL. XCn, No. 242 Maneht*ster A City of yiliage (.harm TWENTY-FOUR PAGES — TWO SECTIONS PRICE: FIFTEEN CENTS n Bitter About Export Limits 5 i Battered Farm SUNNY I. U.S. Urged To Discipline Bill Before ^ Clear tonight with patchy fog T j - developing over low-lying areas, then dissipating after Its Economy sunrise. Low tonight in the mid The Congress 50s to low 60s. Tuesday will be sunny with the high near 80. TOKYO (AP) - Reflecting mounting Japanese Precipitation probability is bitterness over American trade restrictions. Foreign WASHINGTON (AP) — A battered farm bill, the Alaska near zero through Tuesday. Minister Masayoshi Ohira today called on the United pipeline,, a minimum wage increase and historic legisla-, Winds will be north to States to “exercise an increasing degree of discipline in tion to curb presidential war powers are up for action in northeast at less than 10 miles ■■ I managing its own economy.” Congress this week. per hour tonight. 4^ Ohira told the opening session nations as Japan and the United First up was another try in the House to put out a farm High Low of the ninth U.S.-Japan Joint States should cooperate. ’This bill called off the floor last week because it appeared Anchorage 65 53 Cabinet Meeting on 'Trade and call for cooperation appeared to Boston 78 61 headed for President Nixon’s veto. Economic Affairs that Japan is be a substitute for Henry A. Chicago 76 54 Secretary of Agriculture Earl greatly embarrassed by Kissinger’s proposal last May Denveb 83 55 L. -

Ÿþm Icrosoft W

Athens Sandlot League Team Manual For Coaches, Players & Parents ATHENS SANDLOT BOARD OF DIRECTORS President Bill Fournier 590-8659 [email protected] Vice-President Keith McGrath 590-0984 [email protected] Secretary Bob Staron 593-2409 [email protected] Treasurer Kevin Schwarzel 591-1630 [email protected] Legal Counsel George McCarthy 593-3357 [email protected] Player Rep. & Safety Mike Rider 707-3586 [email protected] 2007 SANDLOT COMMISSIONERS 12U Bob Staron 593-2409 [email protected] 12U George McCarthy 593-3357 [email protected] 12U/10U Softball Roger Bissell 591-4002 [email protected] 12U/10U Softball Paul Carey [email protected] 10U Tom Vander Ven 707-7312 [email protected] 10U Trevis Thompson 707-9559 [email protected] 7-8 Kris Kostival 590-2141 [email protected] 7-8 Chris Stewart 591-4605 [email protected] 1 Dear Coaches, Players, and Parents: This Team Manual contains instruction and information for how we would like to see each of the Sandlot teams play baseball. “Team” is the best term to use to describe the type of baseball that we want to teach and encourage our young players to The execute on the field. Another most important word you will hear often is “HUSTLE”. Hustle is the one thing every player can do well, regardless of his/her level of athletic best ability. You might be wondering why we are giving you a team manual for teams ranging in work ages from 7 years old to 12 years old. You may wonder, is this really necessary? We believe so. -

The Psychology of Baseball: How the Mental Game Impacts the Physical Game

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Honors Scholar Theses Honors Scholar Program Spring 4-26-2018 The syP chology of Baseball: How the Mental Game Impacts the Physical Game Kiera Dalmass [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses Part of the Applied Statistics Commons, Comparative Psychology Commons, and the Design of Experiments and Sample Surveys Commons Recommended Citation Dalmass, Kiera, "The sP ychology of Baseball: How the Mental Game Impacts the Physical Game" (2018). Honors Scholar Theses. 578. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses/578 Student Researcher: Kiera Dalmass; PI: Haim Bar, Ph.D. Protocol Number: H17-238 The Psychology of Baseball: How the Mental Game Impacts the Physical Game Kiera Dalmass PI: Haim Bar, PhD. University of Connecticut Department of Statistics 1 Student Researcher: Kiera Dalmass; PI: Haim Bar, Ph.D. Protocol Number: H17-238 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 3 ABSTRACT 4 LITERATURE REVIEW 5 RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESIS 14 METHODS 16 PARTICIPANTS 17 MATERIALS 18 PROCEDURE 21 RESULTS 24 STATISTICAL RESULTS SURVEY RESULTS DISCUSSION 58 LIMITATIONS OF STUDY 59 FINDINGS AND FUTURE OF THE STUDY 60 REFERENCES 64 APPENDIX A: DEFINITIONS AND FORMULAS FOR VARIABLES 66 APPENDIX B: SURVEYS 68 APPENDIX C: INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD FORMS 75 2 Student Researcher: Kiera Dalmass; PI: Haim Bar, Ph.D. Protocol Number: H17-238 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my family for always being my support system and helping me achieve my dreams. I would like to give a special thank you to Professor Haim Bar, my research mentor. Without him, none of this project would have been possible. -

Hillsborough Claims District 52 9-10S Title Behind Pitching Gem | Sports | Smdailyjournal.Com 7/5/17, 4(00 PM

Hillsborough claims District 52 9-10s title behind pitching gem | Sports | smdailyjournal.com 7/5/17, 4(00 PM FEATURED Hillsborough claims District 52 9-10s title behind pitching gem By Terry Bernal Daily Journal Staff Jul 5, 2017 Updated 1 hr ago It’s an old baseball adage — if a pitcher throws a shutout and “He had the fastest arm we’ve seen, so he was throwing heat,” hits a home run, it’s a guaranteed win. The same can be said of San Mateo National manager Dan Luzzi said. “And that a near-perfect shutout gem combined with going 4 for 4 at the curveball was working for him. He was just great.” plate with three runs scored. And the efficiency was something not often seen from a 10- That’s precisely what Hillsborough 10-year-old Anakin Manuel year-old pitcher. While three different National pitchers did Tuesday night in the District 52 Little League 9-10s All-Star combined to issue four walks and a hit batsman — fairly Tournament championship game. Not only did Manuel notch a perfect 4-for-4 performance at the plate, he came within one routine totals for the 9-10s bracket — Manuel allowed nothing hit of perfection on the mound, facing one batter over the wild. minimum to fire a one-hit shutout to lead Hillsborough to the District 52 crown at Ford Field with a 9-0 win over San Mateo Not only that. Of the 19 batters he faced, he started 17 of them National. with first-pitch strikes. -

Pawlowski's Pitching Principles

Pawlowski’s Pitching Principles John Pawlowski Auburn University Head Baseball Coach Dear Friend; Thank you for purchasing "Pawlowski's Pitching Principle's"! I trust that you will find it both informative and useful in your pitching endeavors. This manual is a "must have" for pitchers and coaches of all levels. In it you will learn about: The Formula for Success Mechanics Pitches Long Toss Pitching Charts Reading Swings Fielding Weight Lifting & Conditioning Nutrition If you would like additional information on instructional videos, products, and camps for baseball teams, players, and coaches please visit my web site at www.Throw90.com Thanks again! Sincerely, Coach John Pawlowski Table of Contents Introduction Formula Mechanics Pitches Long Toss Charts Reading Swings Fielding Weightlifting Nutrition THROW90 BASEBALL Winning is not everything – But making the effort to win is. Vincent Lombardi To be a Winning Pitcher one must: 1. Be in his best physical condition. 2. Be in his best mental condition. 3. Have good control. 4. Have a thorough knowledge of the opposition. 5. Have knowledge and recognition of game situations. 6. Develop and refine his own style of pitching. 7. Knowledge of pitch selection. 8. Know how and be able to field his position. 9. Have poise and self-confidence on the mound. 1. Conditioning – Physical Proper conditioning is when the pitcher is capable of performing his job on a consistent basis without abnormal fatigue. The arm must be in good condition as well as the legs and the other parts of the body used in playing the position of a pitcher. A. -

Investigation of UCL Tears in Baseball Pitchers

Investigation of UCL Tears in Baseball Pitchers A Major Qualifying Project Submitted to the Faculty of Worcester Polytechnic Institute in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering by Maddie Brennan Stephen Gallagher Benedict Kurtze Paula Sardi Date: 4/ 25 / 2019 Advisor: Professor Marko Popovic Co-Advisor: Professor Selçuk Guçeri INVESTIGATION OF UCL 2 Abstract Tearing of the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) is one of the most common injuries for baseball pitchers. During a pitch, the UCL experiences high levels of stress between the cocking and acceleration phase due to a valgus moment. Because this stress cannot be directly measured in vivo, a pitching robot with numerous biomimetic features was created to gain a better understanding of these forces during a fastball pitch. This robotic research platform was then used to design a brace that reduces the amount of stress the ligament undergoes, potentially prolonging the play time for athletes. The robotic arm, in the form of a human skeletal replica, featured seven independently, pneumatically actuated Hydro Muscles and a biomimetic UCL. When the brace was used on the robotic arm, the force on the artificial UCL decreased during the pitching phases which validated its effectiveness. INVESTIGATION OF UCL 3 Acknowledgements The completion of this project would have not been possible without the support of our advisor, Professor Marko Popovic, and our co-advisor, Professor Selçuk Guçeri. We greatly appreciate their constructive feedback, as well as their advice for approaching problems along the way. We also benefited from the equipment and resources in Popovic Labs. -

2019 Texas League Media Guide (.Pdf)

2 3 TEXAS LEAGUE MEDIA GUIDE ADVERTISERS AMI . .88 BairFind . .4 Frost Bank . .2 HBK CPA’s & Consultants . .3 HIBU . .89 Minor League Baseball . .9 Rawlings . .90 4 TEXAS LEAGUE OFFICIALS, MANAGERS AND UMPIRES THE TEXAS LEAGUE OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL CLUBS 505 Main St #250. • Fort Worth, TX 76201 (682) 316-5400 Web Site: www.texasleague.com Email: [email protected] PRESIDENT .................................................................................................. Tim Purpura VICE PRESIDENT .....................................................................................Monty Hoppel SECRETARY .............................................................................................Andy Milovich ASSISTANT TO THE PRESIDENT....................................................Jessica McClasky LEAGUE STATISTICIAN ..............................Major League Baseball Advanced Media UMPIRES Andrew Barrett, Isaias Barba, Michael Carroll, Darius Ghani, Jeffery Gorman, Luis Hernandez, Jose Matamoros, Tyler Olson, , Justin Robinson, Andrew Stukel, Kyle Wallace, Brian Walsh LEAGUE DIRECTORS D.G. Elmore, Amarillo; Russ Meeks, Arkansas; Ken Schrom, Corpus Christi; Chuck Greenberg, Frisco; E. Miles Prentice, Midland; Jon Dandes, Northwest Arkansas; Matt Gifford, Springfield; Mike Melega, Tulsa. FIELD MANAGERS – NORTH DIVISION Arkansas....................................................................................................... Mitch Canham Northwest Arkansas .................................................................................. -

Pitcher Effectiveness, That Uses Statcast Data to Evaluate Starting Pitchers Dynamically, Based on the Results of In-Game Outcomes After Each Pitch

Pitcher Effectiveness: A Step Forward for In Game Analytics and Pitcher Evaluation Christopher Watkins1,*, Vincent Berardi2, Cyril Rakovski3 1Computational and Data Sciences Program, Chapman University, Orange, CA, 2Psychology Department, Chapman University, Orange, CA, 3Mathematics Department, Chapman University, Orange, CA *Corresponding Author E-mail: [email protected] Abstract With the introduction of Statcast in 2015, baseball analytics have become more precise. Statcast allows every play to be accurately tracked and the data it generates is easily accessible through Baseball Savant, which opens the opportunity for improved performance statistics to be developed. In this paper we propose a new tool, Pitcher Effectiveness, that uses Statcast data to evaluate starting pitchers dynamically, based on the results of in-game outcomes after each pitch. Pitcher Effectiveness successfully predicts instances where starting pitchers give up several runs, which we believe make it a new and important tool for the in-game and post-game evaluation of starting pitchers. Keywords: Baseball, MLB, Statcast, Analytics, Prediction 1 Introduction 1.1 Evolution of Statistics in Baseball Baseball has quickly become one of the most analyzed sports with significant growth in the last 20 years (Koseler and Stephan 2017) with an enormous amount of data collected every game that requires professional teams to have a state-of the-art analytics team in order to compete in today’s game. As an example, the Houston Astros lost over 100 games each season from 2011-2013. In 2014, sports writer Ben Reiter predicted the Astros to win a World Series sooner rather than later, in 2017, because of the advanced analytics team they built (Reiter 2014). -

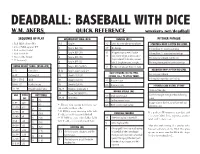

Quick Reference.Indd

DEADBALL: BASEBALL WITH DICE W.M. AKERS QUICK REFERENCE wmakers.net/deadball SEQUENCE OF PLAY ADVANCED HIT TABLE (D20) DEFENSE (D12) PITCHER FATIGUE 1. Roll MSS (d100+PD) 1-2 Single+ 1-2 Error. Runners take an extra base. STARTERS DROP A PITCH DIE LEVEL 2. Check MSS against BT 3 Single, DEF (1B) 3-9 No change 3. Roll on Hit Table* If they allow 3+ runs in an inning 4. Roll for DEF* 4 Single, DEF (2B) 10- Hit goes down a level. Double If they allow 4+ runs over two innings 5. Record the Result 11 reduced to single, runners adv. 2. 5 Single, DEF (3B) For every run allowed over 4 runs *: If Necessary Triple reduced to double, runners 6 Single, DEF (SS) adv. 3. Single remains a single. For every inning pitched past six innings SWING RESULT TABLE (D100+PD) 7 Single, DEF (SS/2B*) 12 Hit turned into out. Runners hold. RELIEVERS DROP A PITCH DIE LEVEL 0 - 5 Critical hit 8-12 Single, runners adv. 2+ BASE STEALING (D8 TO STEAL For every run allowed 6 - BT Ordinary hit 13 Double, DEF (LF) SECOND, D8-1 TO STEAL THIRD) If they pitch more than one inning BT+1 - BT+5 Walk 14 Double, DEF (CF) 1-3 Runner is out BT+6 - 70 Productive out 15 Double, DEF (RF) 4-8 Runner is safe PITCHERS GAIN A LEVEL IF THEY 71 - 99 Possible double play 16-17 Double, runners adv. 3 DOUBLE STEALS (D8) Strike out the side 18 Triple, DEF (RF/CF**)+ ERA PITCH OUT TABLE 1-3 Lead runner is out Go three straight innings without allowing DIE 19-20 Home Run a run 0 (K) 4-5 Trailing runner is out 0-.99 d20 Escape a bases-loaded, no-out jam without 1 (K) +: Players with certain traits have spe- 6-8 Both runners reach safely allowing a run 1-1.99 d12 cial results on these rolls. -

REPLAY BASEBALL Welcome to REPLAY

Welcome to REPLAY BASEBALL © 2010 Replay Publishing In 1973, John Brodak and Norm Roth, avid baseball fans and tabletop baseball gamers, wanted to invent a baseball board game that incorporated all the details of the sport they wanted to see but in a simple, easy-flowing way. Their creation, Replay Baseball , has been enjoyed by thousands of baseball board game fans around the globe ever since. Over the years, the game has been fine-tuned with new features, as the world of baseball statistics has evolved and these new ideas have been translated to the Replay tabletop. What makes Replay Baseball special? Replay established its niche in tabletop baseball with its most unique feature: A pitcher’s or fielder’s rating is added to a batter’s rating, allowing both sides the chance to influence every play. The defensive team’s rating is al- ways in the 1 to 5 range, keeping the math simple. Using this offense + defense system, play results are found in a simple Chart Book, reading in a unique narrative style which adds to the baseball ‘feel’ when playing a game of Replay. Within Replay’s Chart Book and expansive Rare Play Book, nearly all baseball plays and situations are possible. Playability was key to Norm and John, so another strength of the game is its ability to distill even more complex baseball concepts into a game that can be played in 30 minutes or less on the tabletop. Originally played with two six-sided dice, more recently Replay Baseball can also be played with three dice, allowing even greater variety of outcomes and a finer degree of precision to ratings when used. -

Kim-And-King-Matthew-Effects.Pdf

SEEING STARS: MATTHEW EFFECTS AND STATUS BIAS IN MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL UMPIRING Jerry W Kim Columbia University Brayden G King Northwestern University ABSTRACT Despite a growing body of research about the Matthew Effect and status, we still know little about the cognitive biases that underlie the ability of high status actors to accumulate advantages over their lower status peers. In this paper we test the assumption that actors’ status biases evaluators’ judgments made about those actors’ quality. We posit that high status actors benefit from over-recognition of quality, wherein evaluators are more likely to erroneously attribute high quality to an actor’s performance, and that evaluators systematically and erroneously under- recognize quality in low status actors. Using unique data from Major League Baseball umpires’ evaluation of pitch quality, which allow us to observe the difference in a pitch’s objective quality and in its perceived quality as judged by the umpire, we show that umpires are more likely to over-recognize quality in high status pitchers and under-recognize quality in low status pitchers. Ambiguity and the pitcher’s reputation as a “control pitcher” moderate the effect of status on umpire judgment. Further, we show that umpire errors resulting from status bias lead to actual performance differences, decreasing the probability that high status pitchers allow players to get on base and increasing the likelihood of winning the game. Keywords: Status, Cognition, Bias, Performance Authors in alphabetical order. We benefitted from helpful comments by Jeremy Freese, Bruce Kogut, Ko Kuwabara, Damon Phillips, Lauren Rivera, Michael Sauder, and Olav Sorenson. 1" " Sociologists have long understood status to be an indicator of hierarchical position and prestige that helps individuals and organizations procure resources and opportunities for advancement (e.g., Whyte 1943; Podolny 2001). -

New Approaches to Historical Pitcher Evaluation Using DRA 3

New Approaches F to Historical Pitcher Evaluation Using DRA In 2001, Voros McCracken published an article at baseballprospectus.com in which he introduced to the public the idea that pitchers have surprisingly little control over the outcomes of at-bats, excluding strikeouts and home runs, or “batting average on balls in play” (“BABIP”). McCracken found that there was an extremely low correlation in each pitcher’s BABIP from year to year, and that most long-term BABIP rates for pitchers were very similar. Veteran baseball analyst Craig Wright immediately identifi ed two particular groups of pitchers that tend to have noticeably lower BABIP (extreme fl y ball pitchers and knuckleball pitchers), but praised McCracken as “… the guy who really got people to understand that most folks overestimate the pitch- er’s ability to infl uence the number of hits that result from balls batted into the fi eld of play.” In contrast, McCracken found that walk, strikeout, and, to a lesser extent, home run rates of each pitcher were far more consistent year-to-year and varied greatly over long periods of time from pitcher to pitcher. McCracken therefore proposed that pitchers should be evaluated by the statistics over which they have the most control, that are “independent” of the quality of the defenses behind them — strikeouts, walks, and home runs. McCracken developed a method for converting these elements directly into another sta- tistic, scaled the same as ERA, that he called Defense Independent Pitching Statistics (“DIPS”). In 2003, I introduced the basic ideas of DRA in an on-line article at the predecessor website to baseballthinkfactory.com.