Volume 23 Number 2 September 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

System Notes

System Notes James Sundstrom Nathan Savir April 9, 2009 Notation Legend M Either Major. If used multiple times, it always refers to the same major. For example, 1M-2| -2M means either the auction 1~ -2| - 2~ or 1♠ -2| -2♠ , no other auction. m Either minor. As per M. OM Other major. This is only used after 'M', such as 1m-1M-2NT-3OM. om Other minor. As per OM. R Raise. Used in some of the step based system to mean a simple raise, such as 1~ -2~ . DR Double Raise. Q Cuebid. Acknowledgements Special thanks are owed to Blair Seidler, without whose teaching I probably would not ever have written these notes. If I did write them, they surely would not be nearly as good as they are. These notes are a (mostly very-distant) relative of his Carnage notes, though a few sections have been borrowed directly from Carnage. 1 Contents I Non-Competitive Auctions4 1 Opening Bid Summary6 2 Minor Suit Auctions7 2.1 Minor-Major................................7 2.1.1 Suit Bypassing Agreements...................7 2.1.2 New Minor Forcing........................7 2.1.3 Reverses..............................8 2.2 Minor Oriented Auctions.........................8 2.3 NT Oriented auctions...........................8 2.4 Passed Hand Bidding...........................8 3 Major Suit Auctions9 3.1 1 over 1 Auctions.............................9 3.2 Major Suit Raise Structure........................9 3.2.1 Direct Raises...........................9 3.2.2 Bergen...............................9 3.2.3 Jacoby 2NT............................9 3.2.4 3NT................................ 10 3.2.5 Splinters.............................. 10 3.3 Passed Hand................................ 10 3.3.1 Drury.............................. -

CONTEMPORARY BIDDING SERIES Section 1 - Fridays at 9:00 AM Section 2 – Mondays at 4:00 PM Each Session Is Approximately 90 Minutes in Length

CONTEMPORARY BIDDING SERIES Section 1 - Fridays at 9:00 AM Section 2 – Mondays at 4:00 PM Each session is approximately 90 minutes in length Understanding Contemporary Bidding (12 weeks) Background Bidding as Language Recognizing Your Philosophy and Your Style Captaincy Considering the Type of Scoring Basic Hand Evaluation and Recognizing Situations Underlying Concepts Offensive and Defensive Hands Bidding with a Passed Partner Bidding in the Real World Vulnerability Considerations Cue Bids and Doubles as Questions Free Bids Searching for Stoppers What Bids Show Stoppers and What Bids Ask? Notrump Openings: Beyond Simple Stayman Determining When (and Why) to Open Notrump When to use Stayman and When to Avoid "Garbage" Stayman Crawling Stayman Puppet Stayman Smolen Gambling 3NT What, When, How Notrump Openings: Beyond Basic Transfers Jacoby Transfer Accepting the transfer Without interference Super-acceptance After interference After you transfer Showing extra trumps Second suit Splinter Texas Transfer: When and Why? Reverses Opener’s Reverse Expected Values and Shape The “High Level” Reverse Responder’s Options Lebensohl Responder’s Reverse Expected Values and Shape Opener’s Options Common Low Level Doubles Takeout Doubles Responding to Partner’s Takeout Double Negative Doubles When and Why? Continuing Sequences More Low Level Doubles Responsive Doubles Support Doubles When to Suppress Support Doubles of Pre-Emptive Bids “Stolen Bid” or “Shadow” Doubles Balancing Why Balance? How to Balance When to Balance (and When Not) Minor Suit Openings -

A Great Day Out

Editor: Brian Senior • Co-Editor: Ron Klinger Bulletin 7 Layout-Editor: George Georgopoulos Sunday, 14 August 2005 A GREAT DAY OUT The Sydney Opera House as seen from the dinner cruise ship The weather was just perfect for other local landmarks.All in all, one of the yesterday's outing, allowing everyone to best rest days of recent youth champ- have a great time. After leaving the hotel ionships. around lunchtime the first stop was at the Those who did not go on the dinner Koala Park, where there was time to relax cruise would have been impressed with the for a while before enjoying the barbecue organisation and atmosphere surrounding lunch. the rugby union international in the Telstra There was plenty of time after lunch to Stadium, just next to the hotel. Unlike soc- explore the park and, as well as seeing the cer crowds in many parts of the word, the many different species of Australian Australian and New Zealand fans mixed animals, including getting up close enough together happily with no hint of trouble to cuddle koalas, wallabies and even wom- and a good time was had by all — even if bats, there was an exhibition of sheep- the result (a 30-13 win for New Zealand) shearing. Anyone who had never seen an would not have pleased the majority of the expert sheep-shearer at work would have crowd. been amazed at the speed and skill dis- played. VUGRAPH The evening featured a dinner cruise with MATCHES an excellent menu of well-prepared local Poland - Australia 10.00 food. -

About Overcalling

All About Overcalling It is annoying when the opponents open the bidding in front of you, but that doesn’t mean to say that you are constrained to pass for ever. In fact there are quite of number of reasons why it would be right and proper for you to enter the bidding and these can be classified as follows: 1) Because you have a good hand! 2) Because you want to take up bidding space to make things more difficult for the opponents. 3) Because you want to indicate a lead to partner should the hand on your left end up as declarer. 4) Because you might want to pave the way for a possible sacrifice. Sometimes it is better to concede a penalty than let the opponents end up declaring. 1. You have a good hand Suppose you hold: S AQ765 H K2 D A87 C 75 and hear the hand on your right open 1H. As you would have opened the bidding if you had been declarer it seems only sensible that you should bid now and a bid of 1S seems a stand out. And so it is, but there is one requirement that is absolutely sacrosanct whatever the reason you have for overcalling and that is that you must hold at least a five card suit. We shall see in a moment that the suit must have some quality about it, but that is less important if you have a good hand. 2. You want to be difficult In the early days of bridge it was almost considered to be bad form to bid when you didn’t have much in the way of high cards, but that has all changed. -

Supreme Court of the United States ______

No. 16-1275 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States __________ VIRGINIA URANIUM, INC., ET AL., Petitioners, v. JOHN WARREN, ET AL., Respondents. __________ On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit __________ BRIEF OF PREEMPTION LAW PROFESSORS AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS __________ DEREK T. HO Counsel of Record JULIUS P. TARANTO MICHAEL S. QIN KELLOGG, HANSEN, TODD, FIGEL & FREDERICK, P.L.L.C. 1615 M Street, N.W. Suite 400 Washington, D.C. 20036 (202) 326-7900 September 4, 2018 ([email protected]) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ...................................... iii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................... 2 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................... 3 ARGUMENT ............................................................... 4 I. A Legislative-Motive Inquiry Here Would Be Unique In Preemption Doc- trine And An Outlier In Constitutional Doctrine Generally ........................................... 4 A. This Court Has Consistently Held That States’ Intent Is Irrelevant to Preemption .................................................. 4 B. Judicial Scrutiny of Legislative Motive Is Disfavored in Constitu- tional Law Generally .................................. 8 II. Preemption Should Not Turn On Subjec- tive Legislative Intent .................................... 10 A. Legislative-Intent Inquiries Raise Serious Conceptual Problems ................... 11 B. Legislative-Intent -

Ha181026-2.Pdf

Board 6 October 26th, 2018 Dealer East, E-W Vul An interesting board for those who like gadgetry. You hold: Q 6 4 3, J 10 9 4 3, J, . 9 7 4, and Partner opens 1NT (15-17). What do you think about that? 1NT probably won’t make, so wouldn’t it be nice if you could find a major suit fit, if there is one. You could bid 2., but what would you do if Partner responds 2? The answer is to bid 2, used by many as Garbage Stayman. It says “I have a weak hand, am running away from 1NT, let’s play this in 2 or 2, you choose which.” Garbage Stayman can be useful when Partner opens 1NT and we have a weak hand with at least 4-4 in the majors. About half the time Partner will actually have a 4-card major which will be a great improvement on playing in 1NT. And when she doesn’t you’ll likely end up in a 4- 3 or 5-3 fit. However, on a bad day, you will use Garbage Stayman with 4-4 in the majors, only to find out that Partner has opened 1NT with 2-2-4-5 shape. Not to worry, playing in 4-2 fits can be most character-forming. ♠ Q 6 4 3 This is the actual layout, and we can see that Garbage ♥ J 10 9 4 3 Stayman hits the jackpot. 1NT has no play, whereas 2 ♦ J makes on the nose against perfect defense, but is likely to ♣ 9 7 4 make an overtrick in real life. -

Strong and Four

STRONG AND FOUR Apr/2020 Table of Contents 1 SYSTEM OVERVIEW ................................................................................................ 1 1.1 OPENING BIDS ................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 DEFENSIVE BIDDING ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 GAME CONVENTIONS ......................................................................................................................... 3 1.4 SLAM CONVENTIONS .......................................................................................................................... 3 1.5 PLAYING CONVENTIONS ..................................................................................................................... 3 2 OPENING ONE OF A SUIT ....................................................................................... 4 2.1 CHOICE OF OPENING BIDS .................................................................................................................. 4 2.1.1 Limited hands (12-16) .............................................................................................................. 4 2.1.2 Strong hands (16-20) ............................................................................................................... 4 2.1.3 What hands to open ................................................................................................................ -

Analysis of Hands Jan 11 Bd 1

Analysis of Hands Jan 11th 2021 Bd 1: A Dlr: North A852 Optimum Vul: None NS 3N+1; +430 AK4 AQ1092 North 109843 W E Q52 KJ3 e a Q104 863 s 1 s J952 84 t t K65 South KJ76 21 N 976 4 3 4 2 4 4 8 N Q107 S 4 3 3 2 4 7 - - - - - E J73 I hope you all opened 1C on the North hand and nothing else. It is not a 2C or 2NT opening. Bidding should be 1C (N) -1S (S) - 2H *(N) – 2NT (S) with a D stop and 3NT by North. Note the 2H* bid is a Reverse bid and should be 17+ (or good 16) –This bid is unlimited and 100% forcing. South only bids 2NT as the S hand is minimum and North raises to 3NT. Note if North has only 16 he would pass 2NT. If you open 2C and after 2D response you bid 3C and have shown no hearts. What I have outlined above has 5clubs and 4 hearts shown by the time we reach 2H. IT IS NOT A 2C OPENING (A Lebensohl 2NT system can be used with reverse bids too, but I have not covered that in my Lebensohl handout) Bd 2: QJ54 Dlr: East -- Optimum Vul: N/S EW 4Hx,W 4Cx; +500 A1065432 74 North 93 W E K1082 A92 e a K10543 K87 s 2 s Q K6532 t t Q108 South A76 N 7 N - 4 - 2 2 QJ876 10 10 S - 4 - 2 3 J9 13 E - - 1 - - AJ9 W 1 - 1 - - This is extremely difficult to bid unless you are playing a strong NT system. -

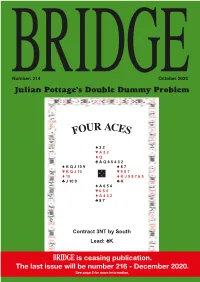

FOUR ACES Could Have Done More Safely

Number: 214 October 2020 BRIDGEJulian Pottage’s Double Dummy Problem UR ACE FO S ♠ 3 2 ♥ A 3 2 ♦ Q ♣ A Q 6 5 4 3 2 ♠ K Q J 10 9 ♠ 8 7 ♥ N ♥ K Q J 10 W E 9 8 7 ♦ 10 S ♦ K J 9 8 7 6 5 ♣ J 10 9 ♣ K ♠ A 6 5 4 ♥ 6 5 4 ♦ A 4 3 2 ♣ 8 7 Contract 3NT by South Lead: ♠K BRIDGE is ceasing publication. The last issueThe will answer be will benumber published on page 216 4 next - month.December 2020. See page 5 for more information. A Sally Brock Looks At Your Slam Bidding Sally’s Slam Clinic Where did we go wrong? Slam of the month Another regular contributor to these Playing standard Acol, South would This month’s hand was sent in by pages, Alex Mathers, sent in the open 2♣, but whatever system was Roger Harris who played it with his following deal which he bid with played it is likely that he would then partner Alan Patel at the Stratford- his partner playing their version of rebid 2NT showing 23-24 points. It is upon-Avon online bridge club. Benjaminised Acol: normal to play the same system after 2♣/2♦ – negative – 2NT as over an opening 2NT, so I was surprised North Dealer South. Game All. Dealer West. Game All. did not use Stayman. In my view the ♠ A 9 4 ♠ J 9 8 correct Acol sequence is: ♥ K 7 6 ♥ A J 10 6 ♦ 2 ♦ K J 7 2 West North East South ♣ A 9 7 6 4 2 ♣ 8 6 Pass Pass Pass 2♣ ♠ Q 10 8 6 3 ♠ J 7 N ♠ Q 4 3 ♠ 10 7 5 2 Pass 2♦ Pass 2NT ♥ Q 9 ♥ 10 8 5 4 2 W E ♥ 7 4 3 N ♥ 9 8 5 2 Pass 3♣ Pass 3♦ ♦ Q J 10 9 5 ♦ K 8 7 3 S W E ♦ 8 5 4 ♦ Q 9 3 Pass 6NT All Pass ♣ 8 ♣ Q 5 S ♣ Q 10 9 4 ♣ J 5 Once South has shown 23 HCP or so, ♠ K 5 2 ♠ A K 6 North knows the values are there for ♥ A J 3 ♥ K Q slam. -

Begin Contract Bridge with Ross Class

Begin contract bridge with Ross www.rossfcollins.com/bridge Class Four Bridge customs. What if you change your mind? Declarer plays a king. You are texting or otherwise woolgathering, and instead of playing low, you accidentally play your queen! Can you take that card back? The rule is this: if you’re still touching the card, we consider that you haven’t definitely played it. But once you let go, too late. You’ll have to suffer the snotty snickers of your opponents and the baleful wails of your partner. Suitable punishment for not paying attention. But the rule also applies to declarer. Who explains it? You can’t explain your bid to your partner, of course. Can you explain it to your opponents? Bridge etiquette requires partnerships to explain all their special or conventional bids (actually, this means not conventional, but artificial, as we’ll consider below) to everyone before the play. Partnerships do not have the right to enjoy secret systems they refuse to explain. But after a bid has been made, an opponent who doesn’t understand what it means may ask the partner of the bidder to explain it (but can’t ask the person who made the bid to explain it). A partner is expected to know what the other partner’s bid means. You’d think that’s a given. But actually, partners frequently forget about the previous agreements they made at the bar after a disastrous defeat. Or they are clueless when a partner throws out an off-the-wall, bat-$!@# crazy bid that, really, nobody can explain. -

Are Counted. the Presence of a 5-Card Suit Is Worth One Point, and the Presence of Tens Can Also Be Taken Into Account

- 1 - INTERMEDIATE-2 BRIDGE LESSON 1 NO TRUMP BIDDING General Considerations: a. Strength - High cards points only (never distribution) are counted. The presence of a 5-card suit is worth one point, and the presence of tens can also be taken into account. The system is based upon 26 HCP's = Game, 34 HCP's = Small Slam, and 37 HCP's = Grand Slam. b. Distribution - Only balanced hands; i.e., no voids, no singletons, and not more than one doubleton, qualify. (Examples: 4-3-3-3, 4-4-3-2, 5-3-3-2) (1) The 5-card suit is rarely a Major suit. (2) Distributional exception: (5-4-2-2) Where the two doubletons are Major suits headed by an Ace or a King (Example: KX AX KJXX AQXXX). c. Location Of Strength - The concentration of honors, presence of any tenaces (AQ, KJ, etc.), or the holding of a worthless doubleton are rarely considered. OPENING NO TRUMP BIDS a. 0-12 HCP’s - Pass b. 13-14 HCP's - Bid one of a preferred Minor and rebid 1NT c. 15-17 HCP’s - Bid 1NT d. 18-20 HCP’s - Open one of a Minor and jump to 2NT with 18 or 19 HCP’s & 3NT with 20 HCP’s e. 21-22 HCP's - Open 2NT f. 23-24 HCP’s - Open “2C”(Strong, Artificial, and Forcing) and rebid 2NT q. 25-27 HCP's - Open "2C" (Strong, Artificial, and Forcing) and jump to 3NT h. Gambling "3NT" - Holding a 7-Card self-sufficient Minor suit (Example: AKQXXXX ) If partner has stoppers in both Majors and two (2) quick tricks or better, he/she passes. -

2021-2022 Secondary Student Handbook TABLE of CONTENTS

STUDENT HANDBOOK SECONDARY E16 - LINDSEY ELEMENTARY M2 - ROBERTS MIDDLE (6) H6 - TERRY HIGH (9-12) ELEMENTARY 2431 Joan Collier Trace 9230 Charger Way 5500 Avenue N E1 - ADOLPHUS ELEMENTARY Katy, TX 77494 Fulshear, TX 77441 Rosenberg, TX 77471 7910 Winston Ranch Pkwy. 832-223-5400, (f) 832-223-5401 832-223-5300, (f) 832-223-5301 832-223-3400, (f) 832-223-3401 Richmond, TX 77406 E17 - LONG ELEMENTARY M3 - RYON MIDDLE (6) DISTRICT SITES 832-223-4700, (f) 832-223-4701 907 Main St. 7901 FM 762 E2 - ARREDONDO ELEMENTARY Richmond, TX 77469 Richmond, TX 77469 S1 - 1621 PLACE 6110 August Green Dr. 832-223-1900, (f) 832-223-1901 832-223-4500, (f) 832-223-4501 117 Lane Dr. #14 Rosenberg, TX 77471 Richmond, TX 77469 E18 - MCNEILL ELEMENTARY M4 - WERTHEIMER MIDDLE (6) 832-223-0950, (f) 832-223-0951 832-223-4800, (f) 832-223-4801 7300 S. Mason Rd. 4240 FM 723 S2 - ADMINISTRATIVE ANNEX E3 - AUSTIN ELEMENTARY Richmond, TX 77407 Rosenberg, TX 77471 832-223-2800, (f) 832-223-2801 832-223-4100, (f) 832-223-4101 3801 Avenue N 1630 Pitts Rd. Rosenberg, TX 77471 Richmond, TX 77406 E19 - MEYER ELEMENTARY M5 - WESSENDORFF MIDDLE (6) 832-223-0400, (f) 832-223-0401 832-223-1000, (f) 832-223-1001 1930 J. Meyer Rd. 5201 Mustang Ave. S3 - ALTERNATIVE E4 - BEASLEY ELEMENTARY Richmond, TX 77469 Rosenberg, TX 77471 832-223-2000, (f) 832-223-2001 832-223-3300, (f) 832-223-3301 LEARNING CENTER 7511 Avenue J 1708 Avenue M Beasley, TX 77417 E20 - MORGAN ELEMENTARY JUNIOR HIGH Rosenberg, TX 77471 832-223-1100, (f) 832-223-1101 32720 FM 1093 832-223-0900, (f) 832-223-0901 J1 - BRISCOE JUNIOR HIGH (7-8) E5 - BENTLEY ELEMENTARY Fulshear 77441 832-223-6200, (f) 832-223-6201 4300 FM 723 S4 - BRAZOS CROSSING 9910 FM 359 Richmond, TX 77406 ADMINISTRATION BUILDING Richmond, TX 77406 E21 - PINK ELEMENTARY 832-223-4000, (f) 832-223-4001 3911 Avenue I 832-223-4900, (f) 832-223-4901 1001 Collins Rd.