Kai'mia the Gymea Lily DREAMING STORIES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Macrobrachium Intermedium in Southeastern Australia: Spatial Heterogeneity and the Effects of Species of Seagrass

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 75: 239-249, 1991 Published September 11 Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. Demographic patterns of the palaemonid prawn Macrobrachium intermedium in southeastern Australia: spatial heterogeneity and the effects of species of seagrass Charles A. Gray* School of Biological Sciences, University of Sydney, 2006, NSW. Australia ABSTRACT. The effects of species of seagrass (Zostera capricorni and Posidonia australis) on spatial and temporal heterogeneity in the demography of estuarine populations of the palaemonid prawn Macrobrachium intermedium across 65 km of the Sydney region, southeastern Australia, were examined. Three estuaries were sampled in 1983 and 1984 to assess the magnitude of intra- and inter- estuary variability in demographic characteristics among populations. Species of seagrass had no effect on the demographic patterns of populations: differences in the magnitude and directions of change in abundances, recruitment, reproductive characteristics, size structures and growth were as great among populations within each species of seagrass as those between the 2 seagrasses Abiotic factors, such as the location of a meadow in relation to depth of water and distance offshore, and the interactions of these factors with recruiting larvae are hypothesised to have greater influence than the species of seagrass in determining the distribution and abundance of these prawns. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity in demography was similar across all spatial scales sampled: among meadows (50 m to 3 km apart) in an estuary and among meadows in all 3 estuaries (10 to 65 km apart). Variability in demographic processes among populations in the Sydney region was most likely due to stochastic factors extrinsic to the seagrasses then~selves.I conclude that the demography of seagrass-dwelling estuarine populations of M. -

Jellyfish Catostylus Mosaicus (Rhizostomeae) in New South Wales, Australia

- MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 196: 143-155,2000 Published April 18 Mar Ecol Prog Ser l Geographic separation of stocks of the edible jellyfish Catostylus mosaicus (Rhizostomeae) in New South Wales, Australia K. A. Pitt*, M. J. Kingsford School of Biological Sciences, Zoology Building, A08 University of Sydney, New South Wales 2006, Australia ABSTRACT: The population structure of the commercially harvested jellyfish Catostylus mosaicus (Scyphozoa, Rhizostomeae) was investigated in estuaries and bays in New South Wales, Australia. Variations in abundance and recruitment were studied in 6 estuaries separated by distances ranglng from 75 to 800 km. Patterns of abundance differed greatly among estuaries and the rank abundance among estuaries changed on 5 out of the 6 times sampling occurred. Great variation in the timing of recruitment was also observed among estuaries. Variations in abundance and recruitment were as extreme among nearby estuaries as distant ones. Broad scale sampling and detailed time series of abundance over a period of 2.7 yr at 2 locations showed no consistent seasonal trend in abundance at 1 location, but there was some indication of seasonality at the second location. At Botany Bay, the abun- dance of medusae increased with distance into the estuary and on 19 out of the 30 times sampling occurred medusae were found at sites adjacent to where rivers enter the bay. Medusae were found to be strong swimmers and this may aid medusae in maintaining themselves in the upper-reaches of estu- aries, where advection from an estuary is least likely. Variability in patterns of abundance and recruit- ment suggested regulation by processes occurring at the scale of individual estuaries and, combined with their relatively strong swimming ability, supported a model of population retention within estuar- ies. -

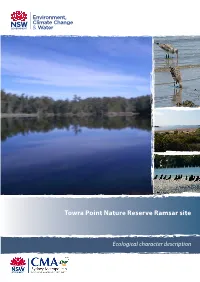

Towra Point Nature Reserve Ramsar Site: Ecological Character Description in Good Faith, Exercising All Due Care and Attention

Towra Point Nature Reserve Ramsar site Ecological character description Disclaimer The Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW (DECCW) has compiled the Towra Point Nature Reserve Ramsar site: Ecological character description in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. DECCW does not accept responsibility for any inaccurate or incomplete information supplied by third parties. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. Readers should seek appropriate advice about the suitability of the information to their needs. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or of the Minister for Environment Protection, Heritage and the Arts. Acknowledgements Phil Straw, Australasian Wader Studies Group; Bob Creese, Bruce Pease, Trudy Walford and Rob Williams, Department of Primary Industries (NSW); Simon Annabel and Rob Lea, NSW Maritime; Geoff Doret, Ian Drinnan and Brendan Graham, Sutherland Shire Council; John Dahlenburg, Sydney Metropolitan Catchment Management Authority. Symbols for conceptual diagrams are courtesy of the Integration and Application Network (ian.umces.edu/symbols), University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. This publication has been prepared with funding provided by the Australian Government to the Sydney Metropolitan Catchment Management Authority through the Coastal Catchments Initiative Program. © State of NSW, Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW, and Sydney Metropolitan Catchment Management Authority DECCW and SMCMA are pleased to allow the reproduction of material from this publication on the condition that the source, publisher and authorship are appropriately acknowledged. -

Coastal Storms in Nsw and Their Effect on the Coast

I I. COASTAL STORMS IN N.s.w. .: AUGUST & NOVEMBER 1986 .1 and Their Effect on the Coast I 'I I 1'1 ! I I I I I I I I I I , . < May 198,8 , 'I " I I : COASTAL STORMS· IN N.s.w. I AUGUST & NOVEMBER 1986 I and Their Effect on the Coast I I I I I 1: 1 I I I I I M.N. CLARKE M.G. GEARY I Chief Engineer Principal Engineer I Prepared by : University of N.S.W. Water Research Laboratory I bID IPTIID311IIcr: ~Th'¥@~ , I May 1988 ------..! Coaat a Rivera Branch I I I I CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ( ii ) I LIST OF TABLES (iv) 1. INTRODUCTION I 2. SUMMARY 2 3. ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS 5 I 3.1 METEOROLOGICAL DATA 5 3.2 TIDE LEVELS 7 3.3 WAVE HEIGHTS AND PERIODS 10 I 3.4 STORM mSTORY - AUGUST 1985 TO AUGUST 1986 13 4. WAVE RUN-UP 15 I 4.1 MANLY WARRINGAH BEACHES 15 4.2 BATEMANS BAY BEACHES 15 I 4.3 THEORETICAL ASSESSMENT 16 4.4 COMPARISON OF MEASURED AND THEORETICAL RUN-UP LEVELS 23 5. BEACH SURVEYS 25 ·1 5.1 GOSFORD BEACHES 25 5.2 MANLY W ARRINGAH BEACHES 28 I 5.3 BATEMANS BAY BEACHES 29 6. OFFSHORE SURVEYS . 30 6.1 SURVEY METHODS 30 I 6.2 GOSFORD BEACHES 30 6.3 WARRINGAH BEACHES 31 I 6.4 ASSESSMENT OF ACCURACY OF OFFSHORE SURVEYS 32 7. OFFSHORE SEDIMENT SAMPLES - GOSFORD BEACHES 34 7.1 SAMPLE COLLECTION 34 I 7.2 SAMPLE CLASSIFICATION 34 , 7.3 SAMPLE DESCRIPTIONS 34 I 7.4 COMPARISON OF 1983/84 AND POST STORM OFFSHORE DATA 36 8. -

![An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [Volume 1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2437/an-account-of-the-english-colony-in-new-south-wales-volume-1-822437.webp)

An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [Volume 1]

An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [Volume 1] With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country. To Which are Added, Some Particulars of New Zealand: Complied by Permission, From the Mss. of Lieutenant-Governor King Collins, David (1756-1810) A digital text sponsored by University of Sydney Library Sydney 2003 colacc1 http://purl.library.usyd.edu.au/setis/id/colacc1 © University of Sydney Library. The texts and images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission Prepared from the print edition published by T. Cadell Jun. and W. Davies 1798 All quotation marks are retained as data. First Published: 1798 F263 Australian Etext Collections at Early Settlement prose nonfiction pre-1810 An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [Volume 1] With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country. To Which are Added, Some Particulars of New Zealand: Complied by Permission, From the Mss. of Lieutenant-Governor King Contents. Introduction. SECT. PAGE I. TRANSPORTS hired to carry Convicts to Botany Bay. — The Sirius and the Supply i commissioned. — Preparations for sailing. — Tonnage of the Transports. — Numbers embarked. — Fleet sails. — Regulations on board the Transports. — Persons left behind. — Two Convicts punished on board the Sirius. — The Hyæna leaves the Fleet. — Arrival of the Fleet at Teneriffe. — Proceedings at that Island. — Some Particulars respecting the Town of Santa Cruz. — An Excursion made to Laguna. — A Convict escapes from one of the Transports, but is retaken. — Proceedings. — The Fleet leaves Teneriffe, and puts to Sea. -

Regional Pest Management Strategy 2012-2017: Metro North East

Regional Pest Management Strategy 2012–17: Metro North East Region A new approach for reducing impacts on native species and park neighbours © Copyright State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage With the exception of photographs, the Office of Environment and Heritage and State of NSW are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. The New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) is part of the Office of Environment and Heritage. Throughout this strategy, references to NPWS should be taken to mean NPWS carrying out functions on behalf of the Director General of the Department of Premier and Cabinet, and the Minister for the Environment. For further information contact: Metro North East Region Metropolitan and Mountains Branch National Parks and Wildlife Service Office of Environment and Heritage PO Box 3031 Asquith NSW 2077 Phone: (02) 9457 8900 Report pollution and environmental incidents Environment Line: 131 555 (NSW only) or [email protected] See also www.environment.nsw.gov.au/pollution Published by: Office of Environment and Heritage 59–61 Goulburn Street, Sydney, NSW 2000 PO Box A290, Sydney South, NSW 1232 Phone: (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Phone: 131 555 (environment information and publications requests) Phone: 1300 361 967 (national parks, climate change and energy efficiency information and publications requests) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 TTY: (02) 9211 4723 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au ISBN 978 1 74293 625 3 OEH 2012/0374 August 2013 This plan may be cited as: OEH 2012, Regional Pest Management Strategy 2012–17, Metro North East Region: a new approach for reducing impacts on native species and park neighbours, Office of Environment and Heritage, Sydney. -

COOK, CUNNINGHAM, HUGHES, MACARTHUR, THROSBY And

BELLS LIN E OF RD RD Riv g C K Y IL k RD ay 1 L Howes Cape Three Points Creek L R Bellbird Hill Hawkesbury D RD R Pie Dish Hill Y Y Cogra Hill DEMONDR Campbells O RR R FE Ettalong RD Mourawaring Point RLY E Bar P L MANS oint M WISE D G D O R R R C E Umina SCENIC E N L A R L T F I THE Belubula Chifley Dam E O V - T K R C D RD S A E E Coxs IN S Bombi Point Y W L E Carcoar N Y RD A A Lake Y G L ON B BELLS W T H PA N I Hawkesbury River A Grose D M R Fish I Grose TA S T A NORTHERN E C River E V K River U C A R R River C R AJ O O F Broken Bay NG R River E River RD B L I D HORNSBY WESTERN W D L W R O IND Y SOR FW RIC BLACKTOW HMON N D W River RD O IC River T IF C JENOLAN A P ITT E N RD T P L S RD T BAY S D A 2 C R D IE Campbells R R W Pittwater A E U N Q Lake C D A R M Rowlands River D R Y E PITTWATER W N BLACKTOWN -IN BAULKHAM HILLS D River D Y S 9 O G S R ALS ESBURY TO Y HAWK N E RD JO H N H D E G R LITHGOW W R A R Y E 2 R R BA E I D L C R W R R T H COOK, CUNNINGHAM, HUGHES, D E I S M C MACQUARIERiver S T H 1 E A O R N M N C D MACKELLAR Lake Oberon O RD N VA S L T D E E A N D 3 V E A M R ON R E A A E G H C MITCHELL H H MACKELLAR W T 10 Y Nepean R R Duckmaloi O L N MACARTHUR, THROSBY and WERRIWA Y MITCHELL R L STERN Y W WE IN MAIN D RD N I D F S 3 F B R O O O R B R R O E Little River E B S W S T E T STLIN GREENWAYK PKW RD M7 CA VALE Y ST Fish LE 7 THE Y A H W N I H O Campbells LL M W CALARE Kedumba RD P W Little BLACKTOWN A NORTH River R WARRINGAH Y BRADFIELDKU-RING-GAI Y C BLUE D I F CHIFLEY I Lane C MAIN BRADFIELD JENOLAN LINDSAY CALARE CHIFLEYRLY -

Lane Cove River Coastal Zone Management Plan

A part of BMT in Energy and Environment "Where will our knowledge take you?" Lane Cove River Coastal Zone Management Plan Offices Prepared For: Lane Cove River Estuary Management Committee Brisbane (LCREMC), Hunters Hill Council, Lane Cove Council, Denver City of Ryde, Willoughby Councli Mackay Melbourne Newcastle Perth Prepared By: BMT WBM Pty Ltd (Member of the BMT group of Sydney companies) Vancouver Acknowledgement: LCREMC has prepared this document with financial assistance from the NSW Government through the Office of Environment and Heritage. This document does not necessarily represent the opinion of the NSW Government or the Office of Environment and Heritage. lANE COVE RIVER CZMP FINAL DRAFT DOCUMENT CONTROL SHEET BMT WBM Pty Ltd Document : Lane Cove River CZMP FINAL BMT WBM Pty Ltd DRAFT Level 1, 256-258 Norton Street PO Box 194 Project Manager : Reid Butler LEICHHARDT NSW 2040 Australia Client : Lane Cove River Estuary Management Committee, Hunters Tel: +61 2 8987 2900 Hill Council, Lane Cove Council, Fax: +61 2 8987 2999 City of Ryde, Willoughby Council ABN 54 010 830 421 www.bmtwbm.com.au Client Contact: Susan Butler (Lane Cove Council) Client Reference: Lane Cove River CZMP Title : Lane Cove River Coastal Zone Management Plan Author/s : Reid Butler, Smita Jha Synopsis : This report provides a revised management plan for the Lane Cove River Estuary under the requirements of the NSW OEH Coastal Zone Management Planning Guidelines. REVISION/CHECKING HISTORY REVISION DATE OF ISSUE CHECKED BY ISSUED BY NUMBER 0 24/05/2012 SJ -

BROOKLYN ESTUARY PROCESS STUDY (VOLUME I of II) By

BROOKLYN ESTUARY PROCESS STUDY (VOLUME I OF II) by Water Research Laboratory Manly Hydraulics Laboratory The Ecology Lab Coastal and Marine Geosciences The Centre for Research on Ecological Impacts of Coastal Cities Edited by B M Miller and D Van Senden Technical Report 2002/20 June 2002 (Issued October 2003) THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES SCHOOL OF CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING WATER RESEARCH LABORATORY BROOKLYN ESTUARY PROCESS STUDY WRL Technical Report 2002/20 June 2002 by Water Research Laboratory Manly Hydraulics Laboratory The Ecology Lab Coastal and Marine Geosciences The Centre for Research on Ecological Impacts of Coastal Cities Edited by B M Miller D Van Senden (Issued October 2003) - i - Water Research Laboratory School of Civil and Environmental Engineering Technical Report No 2002/20 University of New South Wales ABN 57 195 873 179 Report Status Final King Street Date of Issue October 2003 Manly Vale NSW 2093 Australia Telephone: +61 (2) 9949 4488 WRL Project No. 00758 Facsimile: +61 (2) 9949 4188 Project Manager B M Miller Title BROOKLYN ESTUARY PROCESS STUDY Editor(s) B M Miller, D Van Senden Client Name Hornsby Shire Council Client Address PO Box 37 296 Pacific Highway HORNSBY NSW 1630 Client Contact Jacqui Grove Client Reference Major Involvement by: Brett Miller (WRL), David van Senden (MHL), William Glamore (WRL), Ainslie Fraser (WRL), Matt Chadwick (WRL), Peggy O'Donnell (TEL), Michele Widdowson (MHL), Bronson McPherson (MHL), Sophie Diller (TEL), Charmaine Bennett (TEL), John Hudson (CMG), Theresa Lasiak (CEICC) and Tony Underwood (CEICC). The work reported herein was carried out at the Water Research Laboratory, School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of New South Wales, acting on behalf of the client. -

Emergency Survey of Pacific Oysters

Postprint This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published in [Aquaculture] available online 17 December 2013 at http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0044848613006480 Please cite as: Paul-Pont, I., Evans, O., Dhand, N. K., Rubio, A., Coad, P., & Whittington, R. J. (2014). Descriptive epidemiology of mass mortality due to Ostreid herpesvirus-1 (OsHV-1) in commercially farmed Pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas) in the Hawkesbury River estuary, Australia. Aquaculture, 422-423, 146-159. Descriptive epidemiology of mass mortality due to Ostreid herpesvirus-1 (OsHV-1) in commercially farmed Pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas) in the Hawkesbury River estuary, Australia I Paul-Pont1, O Evans1, NK Dhand1, A Rubio2, P Coad2 and RJ Whittington1 1Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Sydney, 425 Werombi Road, Camden NSW 2570, Australia 2Hornsby Shire Council, 296 Pacific Highway, PO Box 37, Hornsby NSW 1630, Australia Corresponding author: RJ Whittington e-mail [email protected]; tel +61 2 93511619; fax +61 2 93511618 Abstract Mortality of farmed triploid Pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas) associated with Ostreid herpesvirus-1 (OsHV-1) was first recorded in Australia in the Georges River/Botany Bay estuary (New South Wales) in late 2010. Two years later, the first sign of possible inter-estuarine spread was observed when commercial triploid Pacific oysters in the Hawkesbury River estuary, located 50 km north of Botany Bay, were affected by mass mortality. The aim of this study was to describe the epidemiological -

A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson Including an Accurate Description of the Situation of the Colony; of the Natives; and of Its Natural Productions

A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson Including An Accurate Description of the Situation of the Colony; of the Natives; and Of Its Natural Productions Tench, Watkin (1759-1833) University of Sydney Library Sydney 1998 http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/ozlit © University of Sydney Library. The texts and Images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission Source Text: Prepared from the print edition published by G. Nicol and J. Sewell. London 1793 All quotation marks retained as data All unambiguous end-of-line hyphens have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line. Author First Published 1789Pre-1840 Australian Etexts pioneers and settlers exploration and explorers (land) pre- 1810 prose nonfiction A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson in New South Wales Including An Accurate Description of the Situation of the Colony; of the Natives; and Of Its Natural Productions London G. Nicol and J. Sewell 1793 TO SIR WATKIN WILLIAMS WYNN, Bart. SIR, A LIFE passed on service, in distant and obscure countries, has hitherto prevented me from aspiring to a personal acquaintance with you. I know you only from the representations of others; not having seen you for the last fourteen years. Consequently I can judge but imperfectly, whether the transactions of a remote and unknown colony will prove sufficiently attractive to engage your attention. Gratitude to a family, from whom I have received the deepest obligations, nevertheless impels me to beg your acceptance of this tribute. Descended of illustrious ancestors, and born to a splendid patrimony, the career of manhood opens before you. -

Networks in a Large-Scale Phylogenetic Analysis: Reconstructing Evolutionary History of Asparagales (Lilianae) Based on Four Plastid Genes

Networks in a Large-Scale Phylogenetic Analysis: Reconstructing Evolutionary History of Asparagales (Lilianae) Based on Four Plastid Genes Shichao Chen1., Dong-Kap Kim2., Mark W. Chase3, Joo-Hwan Kim4* 1 College of Life Science and Technology, Tongji University, Shanghai, China, 2 Division of Forest Resource Conservation, Korea National Arboretum, Pocheon, Gyeonggi- do, Korea, 3 Jodrell Laboratory, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, United Kingdom, 4 Department of Life Science, Gachon University, Seongnam, Gyeonggi-do, Korea Abstract Phylogenetic analysis aims to produce a bifurcating tree, which disregards conflicting signals and displays only those that are present in a large proportion of the data. However, any character (or tree) conflict in a dataset allows the exploration of support for various evolutionary hypotheses. Although data-display network approaches exist, biologists cannot easily and routinely use them to compute rooted phylogenetic networks on real datasets containing hundreds of taxa. Here, we constructed an original neighbour-net for a large dataset of Asparagales to highlight the aspects of the resulting network that will be important for interpreting phylogeny. The analyses were largely conducted with new data collected for the same loci as in previous studies, but from different species accessions and greater sampling in many cases than in published analyses. The network tree summarised the majority data pattern in the characters of plastid sequences before tree building, which largely confirmed the currently recognised phylogenetic relationships. Most conflicting signals are at the base of each group along the Asparagales backbone, which helps us to establish the expectancy and advance our understanding of some difficult taxa relationships and their phylogeny.