Cairo Modern, Khan Al-Khalili, and Midaq Alley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Egyptian Escape with Nile Cruise

with Nile Cruise 11-Day Tour from Cairo to Cairo Cairo – Giza – Karnak – Valley of the Kings Luxor – Edfu – Kom Ombo – Aswan – Philae – High Dam – Cairo November 5 – 15 November 12 – 22 December 3 – 13 $3,649Including Air If you’ve dreamed of standing at the foot of the great pyramids, now is the time to escape to Egypt. Peruse the treasures of King Tutankhamun in Cairo, and answer the riddle of the Sphinx at the Great Pyramids of Giza. Embark on a Nile River cruise YOUR TOUR INCLUDES where you’ll visit the Karnak and Luxor Temples, and join in • 4 nights in Cairo, 4 day Nile river cruise, 1 night in Aswan. guided sightseeing at the Valley of the Kings and Queens on the • Roundtrip air from Fresno, Sacramento, Los Angeles and San Nile’s West Bank. Visit the Temple of Horus with its menacing Francisco to Cairo. Other gateway cities upon request. Intra black stone falcon statue, built 2,000 years ago during the age air flights in Egypt. of Cleopatra. You’ll see fascinating sights, including a bluff-top • Services of a Globus Professional Tour Director. temple to worship crocodile and falcon gods, the unfinished obelisk of the granite quarries of Aswan, and the Temple of Isis • MEALS: Full buffet breakfast daily; 4 lunches; 6 three-course dinners, including welcome and farewell dinner in Cairo. recovered from the submerged island of Philae. Take an excur- sion on a Felucca sail boat for a view of Kitchener’s Island and • HOTELS: (or similar quality if a substitution is required) the mausoleum of Aga Khan. -

THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY in CAIRO School of Humanities And

1 THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY IN CAIRO School of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations Islamic Art and Architecture A thesis on the subject of Revival of Mamluk Architecture in the 19th & 20th centuries by Laila Kamal Marei under the supervision of Dr. Bernard O’Kane 2 Dedications and Acknowledgments I would like to dedicate this thesis for my late father; I hope I am making you proud. I am sure you would have enjoyed this field of study as much as I do. I would also like to dedicate this for my mother, whose endless support allowed me to pursue a field of study that I love. Thank you for listening to my complains and proofreads from day one. Thank you for your patience, understanding and endless love. I am forever, indebted to you. I would like to thank my family and friends whose interest in the field and questions pushed me to find out more. Aziz, my brother, thank you for your questions and criticism, they only pushed me to be better at something I love to do. Zeina, we will explore this world of architecture together some day, thank you for listening and asking questions that only pushed me forward I love you. Alya’a and the Friday morning tours, best mornings of my adult life. Iman, thank you for listening to me ranting and complaining when I thought I’d never finish, thank you for pushing me. Salma, with me every step of the way, thank you for encouraging me always. Adham abu-elenin, thank you for your time and photography. -

The American University in Cairo Press

TheThe AmericanAmerican 2009 UniversityUniversity inin Cairo Cairo PressPress Complete Catalog Fall The American University in Cairo Press, recognized “The American University in Cairo Press is the Arab as the leading English-language publisher in the region, world’s top foreign-language publishing house. It has currently offers a backlist of more than 1000 publica- transformed itself into one of the leading players in tions and publishes annually up to 100 wide-ranging the dialog between East and West, and has produced academic texts and general interest books on ancient a canon of Arabic literature in translation unmatched and modern Egypt and the Middle East, as well as in depth and quality by any publishing house in the Arabic literature in translation, most notably the works world.” of Egypt’s Nobel laureate Naguib Mahfouz. —Egypt Today New Publications 9 Marfleet/El Mahdi Egypt: Moment of Change 22 Abdel-Hakim/Manley Traveling through the 10 Masud et al. Islam and Modernity Deserts of Egypt 14 McNamara The Hashemites 28 Abu Golayyel A Dog with No Tail 23 Mehdawy/Hussein The Pharaoh’s Kitchen 31 Alaidy Being Abbas el Abd 15 Moginet Writing Arabic 2 Arnold The Monuments of Egypt 30 Mustafa Contemporary Iraqi Fiction 31 Aslan The Heron 8 Naguib Women, Water, and Memory 29 Bader Papa Sartre 20 O’Kane The Illustrated Guide to the Museum 9 Bayat Life as Politics of Islamic Art 13 al-Berry Life is More Beautiful than Paradise 2 Ratnagar The Timeline History of Ancient Egypt 15 Bloom/Blair Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art 33 Roberts, R.A. -

Importers Address Telephone Fax Make(S)

Importers Address Telephone Fax Make(s) Alpha Auto trading Josef tito st. Cairo +20 02-2940330 +20 02-2940600 Citroën cars Amal Foreign Trade Heliopolis, Cairo 11Fakhry Pasha St +20 02-2581847 +20 02-2580573 Lada Artoc Auto - Skoda 2, Aisha Al Taimouria st. Garden city Cairo +20 02-7944172 +20 02-7951622 Skoda Asia Motors Egypt 69, El Nasr Road, New Maadi, Cairo +20 02-5168223 +20 02-5168225 Asia Motors Atic/Arab Trading & 21 Talaat Harb St. Cairo +20 02-3907897 +20 02-3907897 Renault CV Insurance Center of 4, Wadi Al nil st. Mohandessin Cairo +20 02-3034775 +20 02-3468300 Peugeot Development & commerce - CDC - Wagih Abaza Chrysler Egypt 154 Orouba St. Heliopolis Cairo +20 02-4151872 +20 02-4151841 Chrysler Daewoo Corp Dokki, Giza- 18 El-Sawra St. Cairo +20 02-3370015 +20 02-3486381 Daewoo Daimler Chrysler Sofitel Tower, 28 th floor Conish el Nil, +20 02-5263800 +20 02-5263600 Mercedes, Egypt Maadi, Cairo Chrysler Egypt Engineering Shubra, Cairo-11 Terral el-ismailia +20 02-4266484 +20 02-4266485 Piaggio Industries Egyptan Automotive 15, Mourad St. Giza +20 02-5728774 +20 02-5733134 VW, Audi Egyptian Int'l Heliopolice Cairo Ismailia Desert Rd: Airport +20 02-2986582 +20 02-2986593 Jaguar Trading & Tourism / Rolls Royce Jaguar Egypt Ferrari El-Alamia ( Hashim Km 22 First of Cairo - Ismailia road +20 02-2817000 +20 02-5168225 Brouda Kancil bus ) Engineering Daher, Cairo 11 Orman +20 02-5890414 +20 02-5890412 Seat Automotive / SMG Porsche Engineering 89, Tereat Al Zomor Ard Al Lewa +20 02-3255363 +20 02-3255377 Musso, Seat , Automotive Co / Mohandessin Giza Porsche SMG Engineering for Cairo 21/24 Emad El-Din St. -

Disclosure Guide

WEEKS® 2021 - 2022 DISCLOSURE GUIDE This publication contains information that indicates resorts participating in, and explains the terms, conditions, and the use of, the RCI Weeks Exchange Program operated by RCI, LLC. You are urged to read it carefully. 0490-2021 RCI, TRC 2021-2022 Annual Disclosure Guide Covers.indd 5 5/20/21 10:34 AM DISCLOSURE GUIDE TO THE RCI WEEKS Fiona G. Downing EXCHANGE PROGRAM Senior Vice President 14 Sylvan Way, Parsippany, NJ 07054 This Disclosure Guide to the RCI Weeks Exchange Program (“Disclosure Guide”) explains the RCI Weeks Elizabeth Dreyer Exchange Program offered to Vacation Owners by RCI, Senior Vice President, Chief Accounting Officer, and LLC (“RCI”). Vacation Owners should carefully review Manager this information to ensure full understanding of the 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 terms, conditions, operation and use of the RCI Weeks Exchange Program. Note: Unless otherwise stated Julia A. Frey herein, capitalized terms in this Disclosure Guide have the Assistant Secretary same meaning as those in the Terms and Conditions of 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 RCI Weeks Subscribing Membership, which are made a part of this document. Brian Gray Vice President RCI is the owner and operator of the RCI Weeks 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 Exchange Program. No government agency has approved the merits of this exchange program. Gary Green Senior Vice President RCI is a Delaware limited liability company (registered as 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 Resort Condominiums -

A Morettian Literary Atlas of Naguib Mahfouz's Cairo in Three Early Realist Novels: Cairo Modern, Khan Al-Khalili, and Midaq Alley

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2015 A Morettian literary atlas of Naguib Mahfouz's Cairo in three early realist novels: Cairo modern, Khan al-Khalili, and Midaq alley Paul A. Sundberg Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Sundberg, P. (2015).A Morettian literary atlas of Naguib Mahfouz's Cairo in three early realist novels: Cairo modern, Khan al-Khalili, and Midaq alley [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/212 MLA Citation Sundberg, Paul A.. A Morettian literary atlas of Naguib Mahfouz's Cairo in three early realist novels: Cairo modern, Khan al-Khalili, and Midaq alley. 2015. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/212 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American University in Cairo School of Humanities and Social Sciences A Morettian Literary Atlas of Naguib Mahfouz’s Cairo in Three Early Realist Novels: Cairo Modern, Khan al-Khalili, and Midaq Alley A Thesis Submitted to The Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts By Paul A. Sundberg Under the supervision of Dr. Hussein Hammouda December/2015 OUTLINE I. INTRODUCTION 1 a. Introduction to the Three Novels 2 b. -

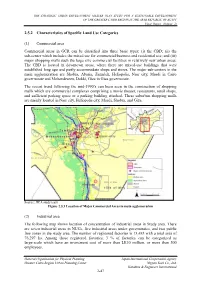

2.5.2 Characteristics of Specific Land Use Categories (1) Commercial

THE STRATEGIC URBAN DEVELOPMENT MASTER PLAN STUDY FOR A SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF THE GREATER CAIRO REGION IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT Final Report (Volume 2) 2.5.2 Characteristics of Specific Land Use Categories (1) Commercial area Commercial areas in GCR can be classified into three basic types: (i) the CBD; (ii) the sub-center which includes the mixed use for commercial/business and residential use; and (iii) major shopping malls such the large size commercial facilities in relatively new urban areas. The CBD is located in downtown areas, where there are mixed-use buildings that were established long ago and partly accommodate shops and stores. The major sub-centers in the main agglomeration are Shobra, Abasia, Zamalek, Heliopolis, Nasr city, Maadi in Cairo governorate and Mohandeseen, Dokki, Giza in Giza governorate. The recent trend following the mid-1990’s can been seen in the construction of shopping malls which are commercial complexes comprising a movie theater, restaurants, retail shops, and sufficient parking space or a parking building attached. These suburban shopping malls are mainly located in Nasr city, Heliopolis city, Maadi, Shobra, and Giza. Source: JICA study team Figure 2.5.3 Location of Major Commercial Areas in main agglomeration (2) Industrial area The following map shows location of concentration of industrial areas in Study area. There are seven industrial areas in NUCs, five industrial areas under governorates, and two public free zones in the study area. The number of registered factories is 13,483 with a total area of 76,297 ha. Among those registered factories, 3 % of factories can be categorized as large-scale which have an investment cost of more than LE10 million, or more than 500 employees. -

An Intermodal Perspective for East Cairo

Higher Committee for Japan International Cooperation Agency Greater Cairo Transportation Planning (JICA) Government of the Arab Republic of Egypt Transportation Master Plan and Feasibility Study of Urban Transport Projects in Greater Cairo Region in the Arab Republic of Egypt Phase 2 FINAL REPORT Vol. III CTA Transport Improvement in East Sector of Cairo December 2003 Pacific Consultants International (PCI) The following foreign exchange rates are applied in this study. USD $1.00 = 6.0 Egyptian Pound (LE) (As of September 2003) PREFACE In response to the request from the Government of the Arab Republic of Egypt, the Government of Japan decided to conduct the Phase 2 Study for “Transportation Master Plan and Feasibility Study of Urban Transport Projects in Greater Cairo Region in the Arab Republic of Egypt” and entrusted the Study to the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). JICA selected and dispatched the study team headed by Dr. Katsuhide Nagayama of Pacific Consultants International to the Arab Republic of Egypt between February 2003 and October 2003. In addition, JICA set up an Advisory Committee headed by Professor Noboru Harata of Tokyo University between February 2003 and January 2004, which examined the Study from the specialist and technical point of view. The Study Team held discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of the Arab Republic of Egypt and conducted field surveys at the study area. Upon returning to Japan, the Study Team conducted further studies and prepared this final report. I hope that this report will contribute to development in the Arab Republic of Egypt, and to the enhancement of friendly relationship between our two countries. -

Cairo International Airport

THE PINNACLE OF PRIVILEGED LIVING 4 6 7 N A Landmark Address One Zamalek stands proud on the Northern tip of Gezira Island, in the elegant and sophisticated Zamalek district. The 21-apartment tower is situated a mere walk from some of Egypt’s most attractive art, culture, dining and lifestyle destinations and just 20km from Cairo International Airport. GEZIRA ISLAND 8 9 Cairo: Enchantingly Enriching Home to One Zamalek, and enviably located Today, the city boasts a truly colourful cultural within reach of both east and west, Cairo is known scene and burgeoning economic landscape, for its millennia of culture, heritage powered by a diverse real estate market and sheer ambition. that has long been attracting attention from discerning investors with an eye for the future. From the pure genius of the pyramids to the inimitable zeal of Cairo’s residents, it is a city that is passionately weaving the threads of its rich past into a breath-taking tapestry that depicts a better tomorrow. 10 11 Life in Zamalek An inimitably eclectic, vibrant neighbourhood With a delightfully eclectic vibe, Zamalek Zamalek is also the unofficial cultural heart is one of Cairo’s most sought-after and premium of Cairo thanks to the iconic Cairo Opera residential neighbourhoods, home to embassies, House, and it was even home to legendary consulates and the city’s well-heeled. songbird, Umm Kulthum. Several magnificent palaces once dotted the district too, Known across Egypt for its abundance and have since been converted into hotels of chic cafes, buzzing nightlife, boutiques and government buildings. -

Directory of Development Organizations

EDITION 2010 VOLUME I.A / AFRICA DIRECTORY OF DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS GUIDE TO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, GOVERNMENTS, PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT AGENCIES, CIVIL SOCIETY, UNIVERSITIES, GRANTMAKERS, BANKS, MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS AND DEVELOPMENT CONSULTING FIRMS Resource Guide to Development Organizations and the Internet Introduction Welcome to the directory of development organizations 2010, Volume I: Africa The directory of development organizations, listing 63.350 development organizations, has been prepared to facilitate international cooperation and knowledge sharing in development work, both among civil society organizations, research institutions, governments and the private sector. The directory aims to promote interaction and active partnerships among key development organisations in civil society, including NGOs, trade unions, faith-based organizations, indigenous peoples movements, foundations and research centres. In creating opportunities for dialogue with governments and private sector, civil society organizations are helping to amplify the voices of the poorest people in the decisions that affect their lives, improve development effectiveness and sustainability and hold governments and policymakers publicly accountable. In particular, the directory is intended to provide a comprehensive source of reference for development practitioners, researchers, donor employees, and policymakers who are committed to good governance, sustainable development and poverty reduction, through: the financial sector and microfinance, -

Trip to Egypt January 25 to February 8, 2020. Day 1

Address : Group72,building11,ap32, El Rehab city. Cairo ,Egypt. tel : 002 02 26929768 cell phone: 002 012 23 16 84 49 012 20 05 34 44 Website : www.mirusvoyages.com EMAIL:[email protected] Trip to Egypt January 25 to February 8, 2020. Day 1 Travel from Chicago to Cairo Day 2 Arrival at Cairo airport, meet & assistance, transfer to the hotel. Overnight at the hotel in Cairo. Day 3 Saqqara, the oldest complete stone building complex known in history, Saqqara features numerous pyramids, including the world-famous Step pyramid of Djoser, Visit the wonderful funerary complex of the King Zoser & Mastaba (Arabic word meaning 'bench') of a Noble. Lunch in a local restaurant. Visit the three Pyramids of Giza, the pyramid of Cheops is the oldest of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, and the only one to remain largely intact. ), the Great Pyramid was the tallest man-made structure in the world for more than 3,800 years. The temple of the valley & the Sphinx. Overnight at the hotel in Cairo. Day 4 Visit the Mokattam church, also known by Cave Church & garbage collectors( Zabbaleen) Mokattam, it is the largest church in the Middle East, seating capacity of 20,000. Visit the Coptic Cairo, Visit The Church of St. Sergius (Abu Sarga) is the oldest church in Egypt dating back to the 5th century A.D. The church owes its fame to having been constructed upon the crypt of the Holy Family where they stayed for three months, visit the Hanging Church (The Address : Group72,building11,ap32, El Rehab city. -

País Região Cidade Nome De Hotel Morada Código Postal Algeria

País Região Cidade Nome de Hotel Morada Código Postal Algeria Adrar Timimoun Gourara Hotel Timimoun, Algeria Algeria Algiers Aïn Benian Hotel Hammamet Ain Benian RN Nº 11 Grand Rocher Cap Caxine , 16061, Aïn Benian, Algeria Algeria Algiers Aïn Benian Hôtel Hammamet Alger Route nationale n°11, Grand Rocher, Ain Benian 16061, Algeria 16061 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Safir Alger 2 Rue Assellah Hocine, Alger Centre 16000 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Samir Hotel 74 Rue Didouche Mourad, Alger Ctre, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Albert Premier 5 Pasteur Ave, Alger Centre 16000 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Hotel Suisse 06 rue Lieutenant Salah Boulhart, Rue Mohamed TOUILEB, Alger 16000, Algeria 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Hotel Aurassi Hotel El-Aurassi, 1 Ave du Docteur Frantz Fanon, Alger Centre, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre ABC Hotel 18, Rue Abdelkader Remini Ex Dujonchay, Alger Centre 16000, Algeria 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Space Telemly Hotel 01 Alger, Avenue YAHIA FERRADI, Alger Ctre, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Hôtel ST 04, Rue MIKIDECHE MOULOUD ( Ex semar pierre ), 4, Alger Ctre 16000, Algeria 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Dar El Ikram 24 Rue Nezzar Kbaili Aissa, Alger Centre 16000, Algeria 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Hotel Oran Center 44 Rue Larbi Ben M'hidi, Alger Ctre, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Es-Safir Hotel Rue Asselah Hocine, Alger Ctre, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Dar El Ikram 22 Rue Hocine BELADJEL, Algiers, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre