Reforming and Developing the School Workforce

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

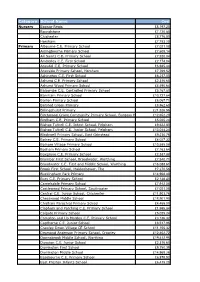

Category School Name Cost Nursery Bognor Regis £8,197.20 Boundstone £7,120.80 Chichester £8,776.80 Horsham £7,783.20 Primary Albourne C.E

Category School Name Cost Nursery Bognor Regis £8,197.20 Boundstone £7,120.80 Chichester £8,776.80 Horsham £7,783.20 Primary Albourne C.E. Primary School £7,021.08 Aldingbourne Primary School £7,609.14 All Saints C.E. Primary School £7,520.04 Amberley C.E. First School £2,174.04 Arundel C.E. Primary School £6,985.44 Arunside Primary School, Horsham £7,769.52 Ashington C.E. First School £6,237.00 Ashurst C.E. Primary School £2,316.60 Ashurst Wood Primary School £4,490.64 Balcombe C.E. Controlled Primary School £5,167.80 Barnham Primary School £10,727.64 Barton Primary School £6,067.71 Bersted Green Primary £8,862.60 Billingshurst Primary £21,526.56 Birchwood Grove Community Primary School, Burgess Hill £12,652.20 Birdham C.E. Primary School £5,025.24 Bishop Tufnell C.E. Infant School, Felpham £9,622.80 Bishop Tufnell C.E. Junior School, Felpham £13,044.24 Blackwell Primary School, East Grinstead £9,230.76 Bolney C.E. Primary School £4,027.32 Bolnore Village Primary School £10,585.08 Bosham Primary School £7,163.64 Boxgrove C.E. Primary School £2,387.88 Bramber First School, Broadwater, Worthing £7,540.71 Broadwater C.E. First and Middle School, Worthing £16,088.61 Brook First School, Maidenbower, The £7,270.56 Buckingham Park Primary £14,968.80 Bury C.E. Primary School £2,138.40 Camelsdale Primary School £7,912.08 Castlewood Primary School, Southwater £7,021.08 Central C.E. Junior School, Chichester £11,903.76 Chesswood Middle School £18,901.90 Chidham Parochial Primary School £4,455.00 Clapham and Patching C.E. -

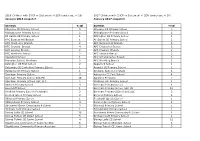

2016 Children with EHCP Or Statement of SEN (Under Age Of

2016 Children with EHCP or Statement of SEN (under age of 16) 2017 Children with EHCP or Statement of SEN (under age of 16) January 2016 snapshot January 2017 snapshot SCHOOL Total SCHOOL Total Albourne CE Primary School 5 Albourne CE Primary School 3 Aldingbourne Primary School 2 Aldingbourne Primary School 2 All Saints CE Primary School 1 Aldrington CE Primary School 1 APC Burgess Hill Branch 1 All Saints CE Primary School 2 APC Chichester Branch 2 APC Burgess Hill Branch 5 APC Crawley Branch 4 APC Chichester Branch 3 APC Lancing Branch, 2 APC Crawley Branch 1 APC Worthing Branch 2 APC Lancing Branch 3 Appleford School 1 APC Littlehampton Branch 1 Arunside School, Horsham 3 APC Worthing Branch 1 Ashington CE First School 2 Appleford School 1 Balcombe CE Controlled Primary School 1 Arundel CE Primary School 1 Baldwins Hill Primary School 1 Arunside School, Horsham 4 Barnham Primary School 3 Ashington CE First School 4 Barnham Primary School SSC PD 10 Awaiting Provision 7 Barnham Primary SChool SSC SLC 2 Baldwins Hill Primary School 4 Bartons Primary School 4 Barnham Primary School 4 Beechcliff School 1 Barnham Primary School SSC PD 10 Benfield Primary School (Portslade) 2 Barnham Primary SChool SSC SLC 3 Bersted Green Primary School 2 Bartons Primary School 4 Bilingual Primary School 1 Beechcliff Special School 1 Billingshurst Primary School 4 Bersted Green Primary School 3 Birchwood Grove Community P School 3 Bilingual Primary School 1 Birdham CofE Primary School 1 Billingshurst Primary School 2 Bishop Luffa CE School 10 Birchwood Grove -

Choosing Your New School With

A Pull Out Choosing your and Keep New School Feature Kids travel with The definitive guide for just to open days for that all important decision. If you have an adult ticket you can buy our ‘kid for a quid’ £1 add-on ticket. This allows you to travel with one child, for one day, for £1. You can buy up to a maximum of four tickets, that’s just £4 for four kids. Now available to buy with concession passes Buy it on the bus, pay cash or contactless Find out more at stagecoachbus.com/kidforaquid Choosing your New School Starting to look at secondary schools? We Make a Shortlist of Schools give you the lowdown on what to do. Firstly, make a shortlist of the schools that your child could attend by looking at nearby local authority’s websites or visit Choosing a secondary school is one of the most www.education.gov.uk. Make sure you check their admission important decisions you are going to make because rules carefully to ensure your child is eligible for a place. You it’s likely to have a huge impact on your child’s also need to be happy that your child can travel to school future, way beyond the school gates. There’s some easily and that siblings, if relevant, could go to the same essential ‘homework’ to be done before you make school. After that, it’s time to take a look at the facts and Choosing your new School that all important choice and you must make sure figures to make a comparison on paper. -

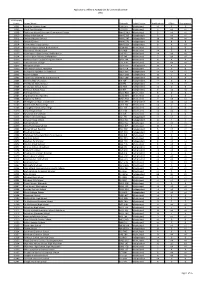

2009 Admissions Cycle

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2009 UCAS Apply Centre School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances 10001 Ysgol Syr Thomas Jones LL68 9TH Maintained <4 0 0 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 4 <4 <4 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 5 <4 <4 10010 Bedford High School MK40 2BS Independent 7 <4 <4 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 18 <4 <4 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 20 8 8 10014 Dame Alice Harpur School MK42 0BX Independent 8 4 <4 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 5 0 0 10020 Manshead School, Luton LU1 4BB Maintained <4 0 0 10022 Queensbury Upper School, Bedfordshire LU6 3BU Maintained <4 <4 <4 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 7 <4 <4 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 8 4 4 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 12 <4 <4 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 15 4 4 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <4 0 0 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent <4 <4 <4 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 15 7 6 10033 The School of St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 22 9 9 10035 Dean College of London N7 7QP Independent <4 0 0 10036 The Marist Senior School SL57PS Independent <4 <4 <4 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent <4 0 0 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 6 <4 <4 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 8 0 0 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained -

School/College Name Post Code Visitors ACS Cobham International School ACS Egham International School Alton College Battle Abbey

School/college name Post code Visitors ACS Cobham International School 80 ACS Egham International School TW20 8UB 45 Alton College GU34 2LX 140 Battle Abbey School, Battle TN33 0AD 53 Carshalton Boys Sports College SM 5 1RW 80 Charters School SL5 9SP 200 Chichester College 81 Chiswick School W4 3UN 140 Christ's College, Guildford GU1 1JY 12 Churcher's College GU31 4AS 136 Claremont Fan Court School KT109LY 65 Cranleigh School, Cranleigh GU68QD 132 Dormers Wells High School, Southall UB1 3HZ 120 Easthampstead Park Community School RG12 8FS 50 Ewell Castle School KT17 AW 27 Farlington School RH12 3PN 15 Farnborough College of Technology GU14 6SB 53 Farnborough Hill GU148AT 35 Farnham College GU98LU 55 Frensham Heights School, Farnham GU10 4EA 50 George Abbot School GU1 1XX 260 Godalming College GU7 1RS 660 Gordon's School GU24 9PT 140 Guildford County School GU27RS 130 Halliford School 34 Hazelwick School RH10 1SX 124 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ 30 Heathside School and Sixth Form KT13 8UZ 110 Highdown School and Sixth Form Centre RG4 8LR 110 Holyport College SL6 3LE 75 Howard of Effingham School KT24 5JR 163 Imberhorne School RH191QY 180 Kendrick School RG1 5BN 145 King Edwards School Witley 70 Lingfield College RH7 6PH 90 Lord Wandsworth College RG29 1TB 77 Luckley House School RG40 3EU 23 Midhurst Rother College - Midhurst Site (was Midhurst GU29 9DT 42 Grammar School) More House School, Farnham GU10 3AP 40 Notre Dame Senior School KT11 1HA 35 Oratory School, Woodcote RG8 0PJ 40 Oriel High School 110 Pangbourne College, Reading -

Home to School Transport Budget

Cabinet Member for Education and Schools Appendix 1 School Summary of comments Midhurst Rother The Principal of the college has written to say that: College Midhurst Rother College has a large rural catchment area covering 400 square miles. Cancelling the service is not an option. The College is committed to offering an extensive range of extra-curricular activities and will honour that intention. Making alternative arrangements or asking parents to pay is not an option. The socio-economic background of the students is such that they come from families of modest economic means. Parental reaction to the proposal has been one of deep dismay, especially those who live in more remote areas. For those who live in the town of Midhurst, there is no difference to what students can access after school. This cannot be said of students who live ‘out in the sticks’ if such transport ended. If the services stop, there would be a drop in pupil attainment. After school study classes for students who are taking public examinations last year resulted in a 12% improvement in the college’s overall 5+ A*-C GCSE figure, an improvement of 10% at AS level and 3% at A level. It would fly in the face of our aspiration to improve students’ attainment if they did not have the means of transport to get home following after-College booster classes. Midhurst Rother College’s location and the background of its students, make it a special case in such matters. The college wishes to retain these services. The rural nature of the college leaves them financially vulnerable to decisions whose impact is felt disproportionately across the county. -

South & South East in Bloom Blooming Schools Results 2014

South & South East in Bloom Blooming Schools Results 2014 Champion of Champions Maidenbower Junior School, Crawley Silver-Gilt Alton Infants School, Alton Gold Herne CE Infant and Nursery School, Herne Bay Gold The Oaks Infant School, Sittingbourne Gold Northern Junior Community School, Fareham Gold & Champion of Champions Winner Dorset Hill View Primary, Bournemouth Silver The Abbey CE VA Primary School, Shaftesbury Silver Wimborne First School, Wimborne Silver Malmesbury Park Primary School, Bournemouth Silver-Gilt Mudeford Infants School, Christchurch Silver-Gilt Queens Park Academy (Junior), Charminster Silver-Gilt St John’s First School, Wimborne Silver-Gilt Stourfield Junior, Bournemouth Gold Yarrells Preparatory School, Upton Gold Chewton Common Playgroup, Highcliffe Gold & Dorset Winner East Sussex Bexhill High, Bexhill on Sea Certificate St. Margaret’s CE School, Rottingdean Bronze Longhill High School, Rottingdean Silver Catsfield Church of England Primary School, Battle Silver-Gilt Forest Row Pre-School, Forest Row Silver-Gilt Moulsecoomb Primary School, Brighton Silver-Gilt Pashley Down Infants School, Eastbourne Silver-Gilt Greenfields School, Forest Row Gold Wivelsfield Primary, Wivelsfield Green Gold & East Sussex Winner Hampshire Eggar’s School, Alton Certificate Amery Hill School, Alton Bronze Wickham Church of England Primary School, Fareham Bronze Anstey Junior School, Alton Silver Cupernham Junior School, Romsey Silver Farnborough Grange Nursery School, Farnborough Silver Flying Bull Primary & Nursery School, Portsmouth Silver Leesland C of E Junior School, Gosport Silver Andrews’ Endowed Primary School, Alton Silver-Gilt Carisbrooke College, Newport Silver-Gilt Court Lane Junior School, Cosham Silver-Gilt East Meon CE Primary School, Petersfield Silver-Gilt Elson Junior School, Gosport Silver-Gilt Foundry Lane Primary School, Southampton Silver-Gilt Leesland C of E Infant School, Gosport Silver-Gilt Rowner Infant School, Gosport Silver-Gilt St. -

Secondary School Cricket

Secondary School Cricket & Stoolball Leaderboard Position School School Games Area Team Average Score 1 Yapton Home Schoolers (Yapton) West Sussex West Wolverines 65.0 2 St Philip Howard Catholic School (Bognor Regis) West Sussex West Wolverines 64.0 3 Cornfield School (Littlehampton) Southern Sharks 63.2 4 Brighton College (Brighton) Brighton & Hove Hawks 63.0 5 Lancing College Preparatory School at Worthing (Worthing) Southern Sharks 62.5 6 Claverham Community College (Battle) Hastings & Rother Leopards 62.0 7 Felpham Community College (Bognor Regis) West Sussex West Wolverines 61.0 8 King's Academy Ringmer (Ringmer) South Downs Giants 60.0 9 Longhill High School (Brighton) Brighton & Hove Hawks 59.0 10 Gildredge House (Eastbourne) South Downs Giants 58.5 11 Ark Alexandra Academy (Hastings) Hastings & Rother Leopards 57.0 11 Roedean Moira House (Eastbourne) South Downs Giants 57.0 13 Patcham High School (Brighton) Brighton & Hove Hawks 56.5 14 Ratton School (Eastbourne) South Downs Giants 56.0 14 The Forest School (Horsham) Central Sussex Dolphins 56.0 14 Worthing High School (Worthing) Southern Sharks 56.0 17 Willingdon Community School (Eastbourne) South Downs Giants 55.4 18 St Richard's Catholic College (Bexhill-on-Sea) Hastings & Rother Leopards 54.8 19 Bishop Luffa School (Chichester) West Sussex West Wolverines 54.4 20 Dorothy Stringer School (Brighton) Brighton & Hove Hawks 54.0 21 Millais School (Horsham) Central Sussex Dolphins 52.3 www.sussexschoolgames.co.uk 22 Weald School, The (Billingshurst) Central Sussex Dolphins 52.0 -

Overall: Secondary School Leaderboard Www

Overall: Secondary School Leaderboard Position School School Games Area Team Points 1 Yapton Home Schoolers (Yapton) West Sussex West Wolverines 46 2 St Philip Howard Catholic School (Bognor Regis) West Sussex West Wolverines 33 3 Beacon Academy (Crowborough) North Wealden Warriors 31 3 Patcham High School (Brighton) Brighton & Hove Hawks 31 5 Lancing College Preparatory School At Hove (Hove) Southern Sharks 28 6 Hove Park School and Sixth Form Centre (Hove) Brighton & Hove Hawks 27 7 King's Academy Ringmer (Ringmer) South Downs Giants 25 7 Ormiston Six Villages Academy (Chichester) West Sussex West Wolverines 25 9 Shoreham College (Shoreham-by-Sea) Southern Sharks 24 10 Rye College (Rye) Hastings & Rother Leopards 23 10 The Academy (Selsey) West Sussex West Wolverines 23 12 Imberhorne School (East Grinstead) Mid Sussex Panthers 21 12 The Towers Convent School (Upper Beeding) Southern Sharks 21 14 Gildredge House (Eastbourne) South Downs Giants 19 14 Oak Grove College (Worthing) Southern Sharks 19 16 Oathall Community College (Haywards Heath) Mid Sussex Panthers 17 16 The Forest School (Horsham) Central Sussex Dolphins 17 www.sussexschoolgames.co.uk 18 Hazelwick School (Crawley) Crawley Cougars 15 18 King's School (Hove) Brighton & Hove Hawks 15 20 Ark Alexandra Academy (Hastings) Hastings & Rother Leopards 10 20 Battle Abbey School (Battle) Hastings & Rother Leopards 10 20 Bishop Luffa School (Chichester) West Sussex West Wolverines 10 20 Blatchington Mill School (Hove) Brighton & Hove Hawks 10 20 Bohunt Horsham (Horsham) Central Sussex -

Schools and Colleges Offering Post-16 Education

Schools and Colleges offering Post-16 education School or College Type of Email address Website Telephone/Fax establishment Numbers The Angmering School School with Sixth Form office@theangmeringschool. www.angmeringschool.co.uk 01903 772351 (T) co.uk 01903 850752 (F) Bishop Luffa CE School, Aided School with Sixth www.bishopluffa.org.uk 01243 787741 (T) Chichester Form The Regis School School with Sixth Form enquiries www.theregisschool.co.uk 01243 871010 (T) @theregisschool.co.uk 01243 871011 (F) Chichester College College of Further [email protected] www.chichester.ac.uk 01243 786321 (T) Education Chichester College – College of Further [email protected] www.chichester.ac.uk 01243 786321 (T) Brinsbury Campus Education Chichester College - Crawley Campus [email protected] www.chichester.ac.uk 01293 442206 (T) Crawley Campus Chichester High School College of Further [email protected] www.chs-tkat.org 01243 787014 (T) Education 01243 832670 (F) The College of Richard College of Further [email protected] www.collyers.ac.uk 01403 210822 (T) Collyer in Horsham Education 01403 211915 (F) Felpham Community School with Sixth Form [email protected] www.felpham.com 01243 826511 (T) College 01243 841021 (F) Fordwater School Special (SLD) [email protected] www.fordwatersch.co.uk 01243 782475 (T) May 2021 Schools and Colleges offering Post-16 education School or College Type of Email address Website Telephone/Fax establishment Numbers Greater Brighton Met College of Further Enquiries- www.gbmc.ac.uk 01903 273060 College – West -

Football: Secondary Schools Leaderboard

Football: Secondary Schools Leaderboard Spirit of the Games Winner: Uckfield College (Uckfield), North Wealden Warriors Placing School School Games Area Team Average Score 1 Brighton College (Brighton) Brighton & Hove Hawks 125.0 2 Felpham Community College (Bognor Regis) West Sussex West Wolverines 118.0 3 Tanbridge House School (Horsham) Central Sussex Dolphins 111.0 4 Cornfield School (Littlehampton) Southern Sharks 102.9 5 St Philip Howard Catholic School (Bognor Regis) West Sussex West Wolverines 102.8 6 The Angmering School (Littlehampton) Southern Sharks 100.1 7 Imberhorne School (East Grinstead) Mid Sussex Panthers 99.0 8 Battle Abbey School (Battle) Hastings & Rother Leopards 97.9 9 Shoreham College (Shoreham-by-Sea) Southern Sharks 97.7 10 Sackville School (East Grinstead) Mid Sussex Panthers 97.5 11 Our Lady of Sion School (Worthing) Southern Sharks 96.7 12 Gildredge House (Eastbourne) South Downs Giants 96.4 13 St Andrew's CofE High School for Boys (Worthing) Southern Sharks 95.8 14 King's Academy Ringmer (Ringmer) South Downs Giants 95.2 www.sussexschoolgames.co.uk 15 Causeway School (Eastbourne) South Downs Giants 95.0 15 The Academy (Selsey) West Sussex West Wolverines 95.0 17 Dorothy Stringer School (Brighton) Brighton & Hove Hawks 93.6 18 Cardinal Newman Catholic School (Hove) Brighton & Hove Hawks 93.3 19 Bishop Luffa School (Chichester) West Sussex West Wolverines 92.6 20 Weald School, The (Billingshurst) Central Sussex Dolphins 92.5 21 Oathall Community College (Haywards Heath) Mid Sussex Panthers 92.4 22 Varndean -

The Winter Games Overall Leaderboard Secondary Schools (19/02/2021)

Specsavers ‘Virtual’ Sussex School Games: The Winter Games Overall Leaderboard Secondary Schools (19/02/2021) Position School SGO Area Team Points 1 Sackville School (East Grinstead) Mid Sussex Panthers 68 2 The Angmering School (Littlehampton) Southern Sharks 53 3 Priory School (Lewes) South Downs Giants 50 4 Tanbridge House School (Horsham) Central Sussex Dolphins 38 4 The Regis School (West Sussex) West Sussex West Wolverines 38 6 St Catherine's College (Eastbourne) South Downs Giants 36 6 St Paul's Catholic College (Burgess Hill) Mid Sussex Panthers 36 8 Millais School (Horsham) Central Sussex Dolphins 34 9 Weald School, The (Billingshurst) Central Sussex Dolphins 33 10 Beacon Academy (Crowborough) North Wealden Warriors 32 11 St Philip Howard Catholic School (Bognor Regis) West Sussex West Wolverines 30 12 Imberhorne School (East Grinstead) Mid Sussex Panthers 28 13 Seaford Head School (Seaford) South Downs Giants 27 14 Cornfield School (Littlehampton) Southern Sharks 26 14 The Burgess Hill Academy (Burgess Hill) Mid Sussex Panthers 26 14 The Eastbourne Academy (Eastbourne) South Downs Giants 26 Specsavers ‘Virtual’ Sussex School Games: The Winter Games Overall Leaderboard Secondary Schools (19/02/2021) Position School SGO Area Team Points 17 Bourne Community College (Emsworth) West Sussex West Wolverines 24 18 Hazelwick School (Crawley) Crawley Cougars 23 19 Oriel High School (Crawley) Crawley Cougars 22 20 Bohunt School Worthing (Worthing) Southern Sharks 20 20 St Oscar Romero Catholic School (Worthing) Southern Sharks 20 22 Oathall