CREATION in the MARKANDEYA PURANA the Brahmanical Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Replication and Innovation in the Folk Narratives of Telangana: Scroll Paintings of the Padmasali Purana, 1625–2000

Manuscript Studies Volume 4 Issue 1 Article 6 2019 Replication and Innovation in the Folk Narratives of Telangana: Scroll Paintings of the Padmasali Purana, 1625–2000 Anais Da Fonseca School of Oriental and African Studies Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/mss_sims Part of the Asian Art and Architecture Commons, Asian History Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Da Fonseca, Anais (2019) "Replication and Innovation in the Folk Narratives of Telangana: Scroll Paintings of the Padmasali Purana, 1625–2000," Manuscript Studies: Vol. 4 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/mss_sims/vol4/iss1/6 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/mss_sims/vol4/iss1/6 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Replication and Innovation in the Folk Narratives of Telangana: Scroll Paintings of the Padmasali Purana, 1625–2000 Abstract In the Southern Indian state of Telangana, itinerant storytellers narrate genealogies of the local castes using a scroll painting on cloth as a visual aid to their performance. These scrolls are the only archive of these otherwise oral narratives; hence key markers of their evolution. Once a scroll commission has been decided, performers bring an old scroll to the painters and request for a ‘copy.’ Considered as such by both performers and painters, a closer look at several scrolls of the same narrative highlights a certain degree of alteration. This paper focuses on the Padmasali Purana that narrate the origin of the weavers’ caste of Telangana. On the basis of five painted scrolls of this same narrative, ranging from 1625 to 2000, this article explores the nature and degree of modification undergone by the narrative. -

Ex Ovo Omnia: Where Does the Balto-Finnic Cosmogony Originate? the Etiology of an Etiology

Oral Tradition, 15/1 (2000): 145-158 Ex Ovo Omnia: Where Does the Balto-Finnic Cosmogony Originate? The Etiology of an Etiology Ülo Valk The idea that the cosmos was born from several eggs laid by a bird is found in the oldest Balto-Finnic myths that have been preserved thanks to the conservative form of runo song. Different versions of the Balto-Finnic creation song were known among the Estonians, the Finns of Ingria, the Votes, and the Karelians.1 The Karelian songs were used by Elias Lönnrot in devising his redaction of the myth in the beginning of the epic Kalevala. Mythical thinking is concerned with questions about the origin of the world and its phenomena; etiologies provide the means to discover and transmit these secrets and to hold magical power over everything. The “quest for origins” has also determined the research interests of generations of scholars employing a diachronic approach. The evolutionist school has tried to reconstruct the primary forms of religion, while the structuralist school of folklore has attempted to discover the basic structures that lie latent behind the narrative surface. The etymologies of Max Müller were aimed at explaining the origin of myths; the geographic-historical or Finnish school once aimed at establishing the archetypes of different items of folklore. That endeavor to elucidate the primary forms and origins of phenomena as the main focus of scholarship can be seen as an expression of neo-mythical thinking. It has become clear that the etiological approach provides too narrow a frame for scholarship, since it cannot explain the meanings of folklore for tradition-bearers themselves, the processes of its transmission in a society, and other aspects that require synchronic interpretation. -

SCIENTISTS Second Edition

the cambridge dictionary of SCIENTISTS second edition David, Ian, John & Margaret Millar PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org © David Millar, Ian Millar, John Millar, Margaret Millar 1996, 2002 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1996 Second edition 2002 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Swift 8/9 pt System Quark XPress A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data The Cambridge dictionary of scientists/David Millar . [et al.]. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-521-80602-X (hardback). – ISBN 0-521-00062-9 (paperback) 1. Scientists–Biography–Dictionaries. 2. Science–History. I. Millar, David. Q141.C128 1996 509.2’2–dc20 95-38471 CIP ISBN 0 521 80602 X hardback ISBN 0 521 00062 9 paperback Contents List of Panels vi About the Authors viii Preface to the Second Edition ix Preface to the First Edition x Symbols and Conventions xi A–Z -

Vidulaku- Mrokkeda-Raga.Html Youtube Class: Audio MP3 Class

Vidhulaku Mrokkedha Ragam: Mayamalavagowlai {15th Melakartha Ragam} https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayamalavagowla ARO: S R1 G3 M1 P D1 N3 S || AVA: A N3 D1 P M1 G3 R1 S || Talam: Adi Composer: Thyagaraja Version: M.S. Subbulakshmi (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=llsETzsGWzU ) Lyrics Courtesy: www.karnatik.com (Rani) and Lakshman Ragde http://www.geocities.com/promiserani2/c2933.html Meaning Courtesy: https://thyagaraja-vaibhavam.blogspot.com/2007/03/thyagaraja-kriti-vidulaku- mrokkeda-raga.html Youtube Class: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hWszTbKSkm0 Audio MP3 Class: http://www.shivkumar.org/music/vidulaku-class.mp3 Pallavi: vidulaku mrokkEda sangIta kO Anupallavi: mudamuna shankara krta sAma nigama vidulaku nAdAtmaka sapta svara Charanam: kamalA gaurI vAgIshvari vidhi garuDa dhvaja shiva nAradulu amarEsha bharata kashyapa caNDIsha AnjanEya guha gajamukhulu su-mrkaNDuja kumbhaja tumburu vara sOmEshvara shArnga dEva nandi pramukhulaku tyAgarAja vandyulaku brahmAnanda sudhAmbudhi marma Meaning Courtesy: https://thyagaraja-vaibhavam.blogspot.com/2007/03/thyagaraja-kriti-vidulaku- mrokkeda-raga.html Pallavi: Sahityam: vidulaku mrokkEda sangIta kO Meaning: I salute (mrokkeda) the maestros (kOvidulaku) of music (sangIta). Sahityam: mudamuna shankara krta sAma nigama vidulaku nAdAtmaka sapta svara Meaning: I joyously (mudamuna) salute - the masters (vidulaku) of sAma vEda (nigama) created (kRta) by Lord Sankara and the maestros (vidulaku) of sapta svara – nAda embodied (Atmaka) (nAdAtmaka). Sahityam:kamalA gaurI vAgIshvari vidhi garuDa dhvaja -

Practice of Ayurveda

PRACTICE OF AYURVEDA SWAMI SIVANANDA Published by THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY P.O. SHIVANANDANAGAR— 249 192 Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttaranchal, Himalayas, India 2006 First Edition: 1958 Second Edition: 2001 Third Edition: 2006 [ 2,000 Copies ] ©The Divine Life Trust Society ISBN-81-7052-159-9 ES 304 Published by Swami Vimalananda for The Divine Life Society, Shivanandanagar, and printed by him at the Yoga-Vedanta Forest Academy Press, P.O. Shivanandanagar, Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttaranchal, Himalayas, India PUBLISHERS’ NOTE Sri Swami Sivanandaji. Maharaj was a healer of the body in his Purvashram (before he entered the Holy Order of Sannyasa). He was a born healer, with an extraordinary inborn love to serve humanity; that is why he chose the medical profession as a career. That is why he edited and published a health Journal “Ambrosia”. That is why he went over to Malaya to serve the poor in the plantations there. And, strangely enough, that is why, he renounced the world and embraced the Holy Order of Sannyasa. He was a healer of the body and the soul. This truth is reflected in the Ashram which he has established in Rishikesh. The huge hospital equipped with modern instruments was set up and the entire Ashram where all are welcome to get themselves healed of their heart’s sores and thoroughly refresh themselves in the divine atmosphere of the holy place. Sri Swamiji wanted that all systems of healing should flourish. He had equal love and admiration for all systems of healing. He wanted that the best of all the systems should be brought out and utilised in the service of Man. -

News Letter Jun2014-Aug2014

Dharma Sandesh kÉqÉïxÉlSåzÉ a quarterly newsletter of Bharatiya Mandir, Middletown, NY AÉ lÉÉå pÉSìÉÈ ¢üiÉuÉÉå rÉliÉÑ ÌuɵÉiÉÈ| Let noble thoughts come to us from everywhere. RigVeda 1.89.1 n Dharma. Let us all pray to the Paramatma (mÉUqÉÉiqÉÉ) to lÉqÉxiÉå Namaste shower His blessings upon all His children!! Á – OM. With the blessings and grace of the Sincerely, Supreme Lord (mÉUqÉÉiqÉÉ), we are proud to start our Your Editorial Board sixth year of the publication of Dharma Sandesh. Web: www.bharatiyamandir.org Email: [email protected] Summer is in full swing here. After the brutal winter, we welcome the warmer weather with open arms and full smiles. People are making vacation plans and xÉÑpÉÉÌwÉiÉÉ Subhaashitaa children are happy that school is almost over. In this section, we present a Sanskrit quotation and its Many children are graduating from high school and interpretation/meaning. college, and they are excited to move on to new and exciting programs and endeavors in their lives. The xÉÇUÉåWÌiÉ AÎalÉlÉÉ SakÉÇ uÉlÉÇ mÉUzÉÑlÉÉ WûiÉqÉç | Mandir, as it does every year, has arranged for a Puja uÉÉcÉÉ SÒÂMçüiÉÇ oÉÏpÉixÉÇ lÉ xÉÇUÉåWÌiÉ uÉÉMçü ¤ÉiÉqÉç || by all the graduating students on Sunday, July 6. All graduates are invited to participate in the Puja and samrohati- agninaa-dagdham-vanam-parashunaa-hatam | seek the blessings of Paramatma (mÉUqÉÉiqÉÉ). vaachaa-duruktam-bibhatsam-na-samrohati-vaak-kshatam|| We will be performing Akhand Ramayan Paath A forest burnt down by a fire will eventually grow (AZÉhQû UÉqÉÉrÉhÉ mÉÉPû) under the guidance of Swami Sri back. A forest cut down by an axe will eventually Madanji of Panchavati Ashram on June 28 and 29. -

Do Creation and Flood Myths Found World Wide Have a Common Origin?

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 5 Print Reference: Pages 517-528 Article 47 2003 Do Creation and Flood Myths Found World Wide Have a Common Origin? Jerry Bergman Northwest State College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Bergman, Jerry (2003) "Do Creation and Flood Myths Found World Wide Have a Common Origin?," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 5 , Article 47. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol5/iss1/47 DO CREATION AND FLOOD MYTHS FOUND WORLD WIDE HAVE A COMMON ORIGIN? Jerry Bergman, Ph.D. Northwest State College Archbold, OH 43543 KEYWORDS: Creation myths, the Genesis account of creation, Noah’s flood ABSTRACT An extensive review of both creation and flood myths reveals that there is a basic core of themes in all of the extant creation and flood myths. This fact gives strong evidence of a common origin of the myths based on actual historical events. -

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

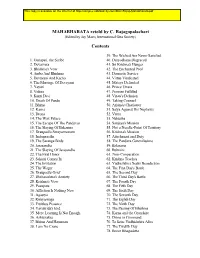

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73. -

Editors Seek the Blessings of Mahasaraswathi

OM GAM GANAPATHAYE NAMAH I MAHASARASWATHYAI NAMAH Editors seek the blessings of MahaSaraswathi Kamala Shankar (Editor-in-Chief) Laxmikant Joshi Chitra Padmanabhan Madhu Ramesh Padma Chari Arjun I Shankar Srikali Varanasi Haranath Gnana Varsha Narasimhan II Thanks to the Authors Adarsh Ravikumar Omsri Bharat Akshay Ravikumar Prerana Gundu Ashwin Mohan Priyanka Saha Anand Kanakam Pranav Raja Arvind Chari Pratap Prasad Aravind Rajagopalan Pavan Kumar Jonnalagadda Ashneel K Reddy Rohit Ramachandran Chandrashekhar Suresh Rohan Jonnalagadda Divya Lambah Samika S Kikkeri Divya Santhanam Shreesha Suresha Dr. Dharwar Achar Srinivasan Venkatachari Girish Kowligi Srinivas Pyda Gokul Kowligi Sahana Kribakaran Gopi Krishna Sruti Bharat Guruganesh Kotta Sumedh Goutam Vedanthi Harsha Koneru Srinath Nandakumar Hamsa Ramesha Sanjana Srinivas HCCC Y&E Balajyothi class S Srinivasan Kapil Gururangan Saurabh Karmarkar Karthik Gururangan Sneha Koneru Komal Sharma Sadhika Malladi Katyayini Satya Srivishnu Goutam Vedanthi Kaushik Amancherla Saransh Gupta Medha Raman Varsha Narasimhan Mahadeva Iyer Vaishnavi Jonnalagadda M L Swamy Vyleen Maheshwari Reddy Mahith Amancherla Varun Mahadevan Nikky Cherukuthota Vaishnavi Kashyap Narasimham Garudadri III Contents Forword VI Preface VIII Chairman’s Message X President’s Message XI Significance of Maha Kumbhabhishekam XII Acharya Bharadwaja 1 Acharya Kapil 3 Adi Shankara 6 Aryabhatta 9 Bhadrachala Ramadas 11 Bhaskaracharya 13 Bheeshma 15 Brahmagupta Bhillamalacarya 17 Chanakya 19 Charaka 21 Dhruva 25 Draupadi 27 Gargi -

Narayana - Wikipedia

10. 10. 2019 Narayana - Wikipedia Narayana Narayana (Sanskrit: , IAST: Nārāyaṇa) is known as one who is in नारायण Narayana yogic slumber on the celestial waters, referring to Lord Maha Vishnu. He is also known as the "Purusha" and is considered Supreme being in नारायण Vaishnavism. According to the Bhagavat Gita, he is also the "Guru of the Universe". The Bhagavata Purana declares Narayana as the Supreme Personality Godhead who engages in the creation of 14 worlds within the universe as Brahma when he deliberately accepts rajas guna, himself sustains, maintains and preserves the universe as Vishnu by accepting sattva guna. Narayana himself annihilates the universe at the end of maha-kalpa as Kalagni Rudra when he accepts tamas guna. According to the Bhagavata Purana, Narayana Sukta, and Narayana Upanishad from the Vedas, he is the ultimate soul. According to Madhvacharya, Narayana is one of the five Vyuhas of Vishnu, which are cosmic emanations of God in contrast to his incarnate avatars. Bryant, Edwin F., Krishna: a Sourcebook. p.359 "Madhvacharya separates Vishnu’s manifestations into two groups: Vishnu’s vyuhas (emanations) and His avataras (incarnations). The Vyuhas have their basis in the A depiction of Lord Narayana at Pancharatras, a sectarian text that was accepted as authoritative by both Badami cave temples the Vishishtadvaita and Dvaita schools of Vedanta. They are mechanisms Affiliation Adi Narayana by which the universe is ordered, was created, and evolves. According to Abode Vaikuntha Madhvacharya, Vishnu has five vyuhas, named Narayana, Vasudeva, Sankarshana, Pradyumna and Aniruddha, which evolve one after the other Mantra ॐ नमो: नारायण in the development of the universe. -

Divine Love in the Medieval Cosmos Te Cosmologies of Hildegard of Bingen and Hermann of Carintiha

Divine Love in the Medieval Cosmos Te Cosmologies of Hildegard of Bingen and Hermann of Carintiha By Jack Ford, University College London Love In every constitution of things Gives herself to all things the most cohesive bond is the Most excellent in the depths, construction of love… the one And above the stars bond of society holding every- Cherishing all… thing in an indissoluble knot. (Hildegard of Bingen, Antiphon for Divine Love)1 (Hermann of Carinthia, De Essentiis)2 Introduction12 things is achieved by love which rules the earth and the seas, and commands the heavens,” exclaims Lady Philosophy, in Troughout the Middle Ages love possessed an exalted the Roman statesman Boethius’ (c.476-526) Consolations status in regard to the cosmos. In a tradition stretching of Philosophy.3 Writing at the end of a great Neoplatonic back to Plato and culminating in Dante’s Divine Comedy, tradition, Boethius was naturally heavily infuenced love was synonymous with an expression of divine power. by Platonic cosmology. It is indeed from Plato’s own In numerous cosmological works, love was believed to cosmological myth, the Timaeus, where we fnd the initial constitute the glue and structure of the universe, and idea of the World-Soul: the soul of the world that Timaeus was employed among the Christian Neoplatonists of the tells Socrates “is interfused everywhere from the center twelfth century as a virtual synonym for the Platonic to the circumference of heaven,” and the same World- World-Soul (anima mundi), the force which emanated Soul which Hildegard and Hermann identify with God’s from the Godhead and fused the macrocosm (the planets, force and power that sustains the cosmos with his love for fxed stars of the frmament, and Empyrean heaven) to creation.4 the microcosm (the terrestrial earth and man) in cosmic Perhaps the greatest fgure to make love synonymous harmony. -

Mandala Brahmana Upanishad OM. the Great Muni Yajnavalkya Went To

Mandala Brahmana upanishad OM. The great Muni Yajnavalkya went to Aditya-Loka (the sun’s world) and saluting him (the Purusha of the Sun) said: “O Revered Sir, describe to me the Atman-Tattva (the Tattva or Truth of Atman).” (To which) Narayana (viz., the Purusha of the sun) replied: “I shall describe the eight- fold Yoga together with Jnana. The conquering of cold and heat as well as hunger and sleep, the preserving of (sweet) patience and unruffledness ever and the restraining of the organs (from sensual objects) - all these come under (or are) Yama. Devotion to one’s Guru, love of the true path, enjoyment of objects producing happiness, internal satisfaction, freedom from association, living in a retired place, the controlling of the Manas and the not longing after the fruits of actions and a state of Vairagya - all these constitute Niyama. The sitting in any posture pleasant to one and clothed in tatters (or bark) is prescribed for Asana (posture). Inspiration, restraint of breath and expiration, which have respectively 16, 64 and 32 (Matras) constitute Pranayama (restraint of breath). The restraining of the mind from the objects of senses is Pratyahara (subjugation of the senses). The contemplation of the oneness of consciousness in all objects is Dhyana. The mind having been drawn away from the objects of the senses, the fixing of the Chaitanya (consciousness) (on one alone) is Dharana. The forgetting of oneself in Dhyana is Samadhi. He who thus knows the eight subtle parts of Yoga attains salvation. Tejo bindu upanishad 30. But it should be directed towards that seat (of Brahman) wherein the cessation of seer, the seen and sight will take place and not towards the tip of the nose.