Greta Garbo and Clarence Brown: an Analysis of Their Professional Relationship in the Context of Classical Hollywood Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who's Who at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)

W H LU * ★ M T R 0 G 0 L D W Y N LU ★ ★ M A Y R MyiWL- * METRO GOLDWYN ■ MAYER INDEX... UJluii STARS ... FEATURED PLAYERS DIRECTORS Astaire. Fred .... 12 Lynn, Leni. 66 Barrymore. Lionel . 13 Massey, Ilona .67 Beery Wallace 14 McPhail, Douglas 68 Cantor, Eddie . 15 Morgan, Frank 69 Crawford, Joan . 16 Morriss, Ann 70 Donat, Robert . 17 Murphy, George 71 Eddy, Nelson ... 18 Neal, Tom. 72 Gable, Clark . 19 O'Keefe, Dennis 73 Garbo, Greta . 20 O'Sullivan, Maureen 74 Garland, Judy. 21 Owen, Reginald 75 Garson, Greer. .... 22 Parker, Cecilia. 76 Lamarr, Hedy .... 23 Pendleton, Nat. 77 Loy, Myrna . 24 Pidgeon, Walter 78 MacDonald, Jeanette 25 Preisser, June 79 Marx Bros. —. 26 Reynolds, Gene. 80 Montgomery, Robert .... 27 Rice, Florence . 81 Powell, Eleanor . 28 Rutherford, Ann ... 82 Powell, William .... 29 Sothern, Ann. 83 Rainer Luise. .... 30 Stone, Lewis. 84 Rooney, Mickey . 31 Turner, Lana 85 Russell, Rosalind .... 32 Weidler, Virginia. 86 Shearer, Norma . 33 Weissmuller, John 87 Stewart, James .... 34 Young, Robert. 88 Sullavan, Margaret .... 35 Yule, Joe.. 89 Taylor, Robert . 36 Berkeley, Busby . 92 Tracy, Spencer . 37 Bucquet, Harold S. 93 Ayres, Lew. 40 Borzage, Frank 94 Bowman, Lee . 41 Brown, Clarence 95 Bruce, Virginia . 42 Buzzell, Eddie 96 Burke, Billie 43 Conway, Jack 97 Carroll, John 44 Cukor, George. 98 Carver, Lynne 45 Fenton, Leslie 99 Castle, Don 46 Fleming, Victor .100 Curtis, Alan 47 LeRoy, Mervyn 101 Day, Laraine 48 Lubitsch, Ernst.102 Douglas, Melvyn 49 McLeod, Norman Z. 103 Frants, Dalies . 50 Marin, Edwin L. .104 George, Florence 51 Potter, H. -

The Only Defense Is Excess: Translating and Surpassing Hollywood’S Conventions to Establish a Relevant Mexican Cinema”*

ANAGRAMAS - UNIVERSIDAD DE MEDELLIN “The Only Defense is Excess: Translating and Surpassing Hollywood’s Conventions to Establish a Relevant Mexican Cinema”* Paula Barreiro Posada** Recibido: 27 de enero de 2011 Aprobado: 4 de marzo de 2011 Abstract Mexico is one of the countries which has adapted American cinematographic genres with success and productivity. This country has seen in Hollywood an effective structure for approaching the audience. With the purpose of approaching national and international audiences, Meximo has not only adopted some of Hollywood cinematographic genres, but it has also combined them with Mexican genres such as “Cabaretera” in order to reflect its social context and national identity. The Melodrama and the Film Noir were two of the Hollywood genres which exercised a stronger influence on the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema. Influence of these genres is specifically evident in style and narrative of the film Aventurera (1949). This film shows the links between Hollywood and Mexican cinema, displaying how some Hollywood conventions were translated and reformed in order to create its own Mexican Cinema. Most countries intending to create their own cinema have to face Hollywood influence. This industry has always been seen as a leading industry in technology, innovation, and economic capacity, and as the Nemesis of local cinema. This case study on Aventurera shows that Mexican cinema reached progress until exceeding conventions of cinematographic genres taken from Hollywood, creating stories which went beyond the local interest. Key words: cinematographic genres, melodrama, film noir, Mexican cinema, cabaretera. * La presente investigación fue desarrollada como tesis de grado para la maestría en Media Arts que completé en el 2010 en la Universidad de Arizona, Estados Unidos. -

State Visit of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Phillip (Great Britain) (4)” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 51, folder “7/7-10/76 - State Visit of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Phillip (Great Britain) (4)” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Betty Ford donated to the United States of America her copyrights in all of her unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON Proposed guest list for the dinner to be given by the President and Mrs. Ford in honor of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and His Royal Highness The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, on Wednesday, July 7, 1976 at eight 0 1 clock, The White House. White tie. The President and Mrs. Ford Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and The Prince Philip Balance of official party - 16 Miss Susan Ford Mr. Jack Ford The Vice President and Mrs. Rockefeller The Secretary of State and Mrs. Kissinger The Secretary of the Treasury and Mrs. Simon The Secretary of Defense and Mrs. Rumsfeld The Chief Justice and Mrs. Burger General and Mrs. -

New Releases Watch Jul Series Highlights

SERIES HIGHLIGHTS THE DARK MUSICALS OF ERIC ROHMER’S BOB FOSSE SIX MORAL TALES From 1969-1979, the master choreographer Eric Rohmer made intellectual fi lms on the and dancer Bob Fosse directed three musical canvas of human experience. These are deeply dramas that eschewed the optimism of the felt and considered stories about the lives of Hollywood golden era musicals, fi lms that everyday people, which are captivating in their had deeply infl uenced him. With his own character’s introspection, passion, delusions, feature fi lm work, Fossae embraced a grittier mistakes and grace. His moral tales, a aesthetic, and explore the dark side of artistic collection of fi lms made over a decade between drive and the corrupting power of money the early 1960s and 1970s, elicits one of the and stardom. Fosse’s decidedly grim outlook, most essential human desires, to love and be paired with his brilliance as a director and loved. Bound in myriad other concerns, and choreographer, lent a strange beauty and ultimately, choices, the essential is never so mystery to his marvelous dark musicals. simple. Endlessly infl uential on the fi lmmakers austinfi lm.org austinfi 512.322.0145 78723 TX Austin, Street 51 1901 East This series includes SWEET CHARITY, This series includes SUZANNE’S CAREER, that followed him, Rohmer is a fi lmmaker to CABARET, and ALL THAT JAZZ. THE BAKERY GIRL OF MONCEAU, THE discover and return to over and over again. COLLECTIONEUSE, MY NIGHT AT MAUD’S, CLAIRE’S KNEE, and LOVE IN THE AFTERNOON. CINEMA SÉANCE ESSENTIAL CINEMA: Filmmakers have long recognized that cinema BETTE & JOAN is a doorway to the metaphysical, and that the Though they shared a profession and were immersive nature of the medium can bring us contemporaries, Bette Davis and Joan closer to the spiritual realm. -

Raymond Burr

Norma Shearer Biography Norma Shearer was born on August 10, 1902, in Montreal's upper-middle class Westmount area, where she studied piano, took dance lessons, and learned horseback riding as a child. This fortune was short lived, since her father lost his construction company during the post-World War I Depression, and the Shearers were forced to leave their mansion. Norma's mother, Edith, took her and her sister, Athole, to New York City, hoping to get them into acting. They stayed in an unheated boarding house, and Edith found work as a sales clerk. When the odd part did come along, it was small. Athole was discouraged, but Norma was motivated to work harder. A stream of failed auditions paid off when she landed a role in 1920's The Stealers. Arriving in Los Angeles in 1923, she was hired by Irving G. Thalberg, a boyish 24-year- old who was production supervisor at tiny Louis B. Mayer Productions. Thalberg was already renowned for his intuitive grasp of public taste. He had spotted Shearer in her modest New York appearances and urged Mayer to sign her. When Mayer merged with two other studios to become Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, both Shearer and Thalberg were catapulted into superstardom. In five years, Shearer, fueled by a larger-than-life ambition, would be a Top Ten Hollywood star, ultimately becoming the glamorous and gracious “First Lady of M-G-M.” Shearer’s private life reflected the poise and elegance of her onscreen persona. Smitten with Thalberg at their first meeting, she married him in 1927. -

Samuels Is Seated As Sheriff; Speaks of Plans Hightower Outspending Republican Votes

; . l I .} 1 . I + " I I'~"'; [ ... I I 1 I' I ': ~.,' .. , 1 ;r.. 1986 Streets were Theyear in photos crowded for holidays SeePage7A SeePage2A ) .' j' ( I. : ' I i·- ". NO. 70 IN OUR 41ST YEAR 35c PER COpy F MONDAY, JANUARY 5, 1987 _RUIDOSO, NM 88345 Sheriff race cost the most by FRANKIE JARRELL votes and Wooldridge 1,351. News Staff Writer Following are the names of can didates, their party affiliation, the Candidates for county offices number of votes received, total ex spent well over $17,000 in cam penditures and total contributions paigns preceding last November's with the names of contributors not general election with would-be previously published listed. Offices sheriffs topping the list. are listed in ballot order and win AccordiIlg to financial reports fil ners are listed first among ed 30 days after the election, write candidates. in candidate Lerry Bond spent DISTRICT MAGISTRATE DIVI more than $3.85 each for the 994 SION I Yotes he garnered in the race for -Gerald Dean Jr., Democrat Uncoln County Sheriff. (D)-2,040 votes. Republican Sheriff Don Samuels' Expenditures: $1,130.85 2,085 votes cost him about 81 cents Contributions: $65. each while bis unsuccessful -Alfred Leroy Montes, Republican Democratic opponent, Jim (R)-1,976 Yotes. Nesmith, spent less than 50 cents Expenditures: $-1,054.51 per vote. Spending by all three Contributions: $800. sheriff candidates was close to '$6,000-. DlSlRlCI- MAGISTR.AXE-.. DIVI Bond reported $2,049.38 on the, SIOND 3O--day report, bringing his total -Jim Wheeler (R)-2,824 votes. -

9781474451062 - Chapter 1.Pdf

Produced by Irving Thalberg 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd i 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd iiii 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM Produced by Irving Thalberg Theory of Studio-Era Filmmaking Ana Salzberg 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd iiiiii 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Ana Salzberg, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/13 Monotype Ehrhardt by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 5104 8 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5106 2 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 5107 9 (epub) The right of Ana Salzberg to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd iivv 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM Contents Acknowledgments vi 1 Opening Credits 1 2 Oblique Casting and Early MGM 25 3 One Great Scene: Thalberg’s Silent Spectacles 48 4 Entertainment Value and Sound Cinema -

Youth Clarence Brown Theatre Clarence Brown Theatre

YOUTH CLARENCE BROWN THEATRE CLARENCE BROWN THEATRE he Clarence Brown Theatre Company is a professional theatre company in residence at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville. Founded in 1974 by Sir Anthony Quayle and Dr. Ralph G. Allen, the company is a member Tof the League of Resident Theatres (LORT) and is the only professional LORT company within a 150-mile radius of Knoxville. The University of Tennessee is one of a select number of universities nationwide that are affiliated with a professional LORT theatre, allowing students regular opportunities to work alongside professional actors, directors, designers, dramaturgs, and production artists. The theatre was named in honor of Knoxville native and University of Tennessee graduate, Clarence Brown, the distinguished MGM director of such beloved films as “The Yearling” and “National Velvet”. In addition to the 575-seat proscenium theatre, the CBT’s facilities house the costume shop, electrics department, scene shop, property shop, actors’ dressing quarters, and a 100-seat Lab Theatre. The Clarence Brown Theatre Company also utilizes the Ula Love Doughty Carousel Theatre, an arena theatre with flexible seating for 350, located next to the CBT on the University of Tennessee campus. The Clarence Brown Theatre has a 19-member resident faculty, headed by Calvin MacLean, and 25 full-time management and production staff members. SEASON FOR YOUTH t the Clarence Brown Theatre, we recognize the positive impact that the performing arts have on young people. We are pleased to continue our commitment to providing high-quality theatre for young audiences Awith our 2013-2014 Season for Youth performances. -

Bibliography Filmography

Blanche Sewell Lived: October 27, 1898 - February 2, 1949 Worked as: editor, film cutter Worked In: United States by Kristen Hatch Blanche Sewell entered the ranks of negative cutters shortly after graduating from Inglewood High School in 1918. She assisted cutter Viola Lawrence on Man, Woman, Marriage (1921) and became a cutter in her own right at MGM in the early 1920s. She remained an editor there until her death in 1949. See also: Hettie Grey Baker, Anne Bauchens, Margaret Booth, Winifred Dunn, Katherine Hilliker, Viola Lawrence, Jane Loring, Irene Morra, Rose Smith Bibliography The bibliography for this essay is included in the “Cutting Women: Margaret Booth and Hollywood’s Pioneering Female Film Editors” overview essay. Filmography A. Archival Filmography: Extant Film Titles: 1. Blanche Sewell as Editor After Midnight. Dir. Monta Bell, sc.: Lorna Moon, ed.: Blanche Sewell (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Corp. US 1927) cas.: Norma Shearer, Gwen Lee, si., b&w. Archive: Cinémathèque Française [FRC]. Man, Woman, and Sin. Dir. Monta Bell, sc.: Alice D. G. Miller, Monta Bell, ed.: Blanche Sewell (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Corp. US 1927) cas.: John Gilbert, Jeanne Eagels, Gladys Brockwell, si., b&w. Archive: George Eastman Museum [USR]. Tell It to the Marines. Dir.: George Hill, sc.: E. Richard Schayer, ed.: Blanche Sewell (Metro- Goldwyn-Mayer Corp. US 1927) cas.: Lon Chaney, William Haines, si, b&w, 35mm. Archive: George Eastman Museum [USR], UCLA Film and Television Archive [USL]. The Cossacks. Dir.: George Hill, adp.: Frances Marion, ed.: Blanche Sewell (Metro-Goldwyn- Mayer Corp. US 1928) cas.: John Gilbert, Renée Adorée, si, b&w. -

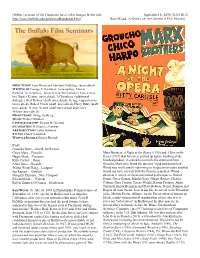

Online Versions of the Handouts Have Color Images & Hot Urls September

Online versions of the Handouts have color images & hot urls September 6, 2016 (XXXIII:2) http://csac.buffalo.edu/goldenrodhandouts.html Sam Wood, A NIGHT AT THE OPERA (1935, 96 min) DIRECTED BY Sam Wood and Edmund Goulding (uncredited) WRITING BY George S. Kaufman (screenplay), Morrie Ryskind (screenplay), James Kevin McGuinness (from a story by), Buster Keaton (uncredited), Al Boasberg (additional dialogue), Bert Kalmar (draft, uncredited), George Oppenheimer (uncredited), Robert Pirosh (draft, uncredited), Harry Ruby (draft uncredited), George Seaton (draft uncredited) and Carey Wilson (uncredited) PRODUCED BY Irving Thalberg MUSIC Herbert Stothart CINEMATOGRAPHY Merritt B. Gerstad FILM EDITING William LeVanway ART DIRECTION Cedric Gibbons STUNTS Chuck Hamilton WHISTLE DOUBLE Enrico Ricardi CAST Groucho Marx…Otis B. Driftwood Chico Marx…Fiorello Marx Brothers, A Night at the Opera (1935) and A Day at the Harpo Marx…Tomasso Races (1937) that his career picked up again. Looking at the Kitty Carlisle…Rosa finished product, it is hard to reconcile the statement from Allan Jones…Ricardo Groucho Marx who found the director "rigid and humorless". Walter Woolf King…Lassparri Wood was vociferously right-wing in his personal views and this Sig Ruman… Gottlieb would not have sat well with the famous comedian. Wood Margaret Dumont…Mrs. Claypool directed 11 actors in Oscar-nominated performances: Robert Edward Keane…Captain Donat, Greer Garson, Martha Scott, Ginger Rogers, Charles Robert Emmett O'Connor…Henderson Coburn, Gary Cooper, Teresa Wright, Katina Paxinou, Akim Tamiroff, Ingrid Bergman and Flora Robson. Donat, Paxinou and SAM WOOD (b. July 10, 1883 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania—d. Rogers all won Oscars. Late in his life, he served as the President September 22, 1949, age 66, in Hollywood, Los Angeles, of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American California), after a two-year apprenticeship under Cecil B. -

HOLLYWOOD – the Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition

HOLLYWOOD – The Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition Paramount MGM 20th Century – Fox Warner Bros RKO Hollywood Oligopoly • Big 5 control first run theaters • Theater chains regional • Theaters required 100+ films/year • Big 5 share films to fill screens • Little 3 supply “B” films Hollywood Major • Producer Distributor Exhibitor • Distribution & Exhibition New York based • New York HQ determines budget, type & quantity of films Hollywood Studio • Hollywood production lots, backlots & ranches • Studio Boss • Head of Production • Story Dept Hollywood Star • Star System • Long Term Option Contract • Publicity Dept Paramount • Adolph Zukor • 1912- Famous Players • 1914- Hodkinson & Paramount • 1916– FP & Paramount merge • Producer Jesse Lasky • Director Cecil B. DeMille • Pickford, Fairbanks, Valentino • 1933- Receivership • 1936-1964 Pres.Barney Balaban • Studio Boss Y. Frank Freeman • 1966- Gulf & Western Paramount Theaters • Chicago, mid West • South • New England • Canada • Paramount Studios: Hollywood Paramount Directors Ernst Lubitsch 1892-1947 • 1926 So This Is Paris (WB) • 1929 The Love Parade • 1932 One Hour With You • 1932 Trouble in Paradise • 1933 Design for Living • 1939 Ninotchka (MGM) • 1940 The Shop Around the Corner (MGM Cecil B. DeMille 1881-1959 • 1914 THE SQUAW MAN • 1915 THE CHEAT • 1920 WHY CHANGE YOUR WIFE • 1923 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS • 1927 KING OF KINGS • 1934 CLEOPATRA • 1949 SAMSON & DELILAH • 1952 THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH • 1955 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS Paramount Directors Josef von Sternberg 1894-1969 • 1927 -

The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Film Studies (MA) Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-2021 The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood Michael Chian Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/film_studies_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chian, Michael. "The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood." Master's thesis, Chapman University, 2021. https://doi.org/10.36837/chapman.000269 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film Studies (MA) Theses by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood A Thesis by Michael Chian Chapman University Orange, CA Dodge College of Film and Media Arts Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Film Studies May, 2021 Committee in charge: Emily Carman, Ph.D., Chair Nam Lee, Ph.D. Federico Paccihoni, Ph.D. The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood Copyright © 2021 by Michael Chian III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my advisor and thesis chair, Dr. Emily Carman, for both overseeing and advising me throughout the development of my thesis. Her guidance helped me to both formulate better arguments and hone my skills as a writer and academic. I would next like to thank my first reader, Dr. Nam Lee, who helped teach me the proper steps in conducting research and recognize areas of my thesis to improve or emphasize.