SECTION 44, MP QUALIFICATIONS and the HIGH COURT Graeme Orr* the Australian Constitution Does Not Explicitly Guarantee a Right to Vote

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drafts As Existing at 19 September 1995

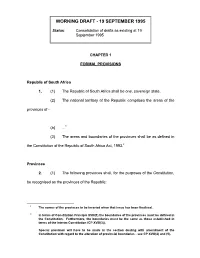

WORKING DRAFT - 19 SEPTEMBER 1995 Status: Consolidation of drafts as existing at 19 September 1995 CHAPTER 1 FORMAL PROVISIONS Republic of South Africa 1. (1) The Republic of South Africa shall be one, sovereign state. (2) The national territory of the Republic comprises the areas of the provinces of - (a) ...1 (3) The areas and boundaries of the provinces shall be as defined in the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Act, 1993.2 Provinces 2. (1) The following provinces shall, for the purposes of the Constitution, be recognised as the provinces of the Republic: 1 The names of the provinces to be inserted when that issue has been finalised. 2 In terms of Constitution Principle XVIII(1) the boundaries of the provinces must be defined in the Constitution. Furthermore, the boundaries must be the same as those established in terms of the Interim Constitution (CP XVIII(3)). Special provision will have to be made in the section dealing with amendment of the Constitution with regard to the alteration of provincial boundaries - see CP XVIII(4) and (5). Working draft: 19 September 1995 (a) ... (b) ... (2) Parliament shall at the request of a provincial legislature alter the name of a province in accordance with the request of such legislature. (3) The areas and boundaries of the respective provinces shall be as established at the commencement of the Constitution.3 2. National symbols4 3. Languages5 4. 3 See Constitutional Principle XVIII. 4 Still under consideration. 5 Still under consideration. - 2 - Working draft: 19 September 1995 CHAPTER 2 CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRACY Citizenship6 5. -

Unit 6 Federalism in Australia

UNIT 6 FEDERALISM IN AUSTRALIA Structure 6.1 Introduction 6.2 Objectives 6.3 The Background 6.4 Nature of Federalism and Division of Powers 6.4.1 Division of Powers 6.4.2 Financial Relations 6.4.3 Dual Judiciary 6.5 Towards Centralisation 6.5.1 Constitutional Amendments 6.5.2 Judicial Support 6.5.3 Powerful Commonwealth 6.6 New Federalism 6.6.1 Hawke's New Federalism 6.6.2 The Significance of Intergovernmental Bodies 6.6.3 The Council of Australian Governments 6.6.4 The Leaders' Forum 6.6.5 Ministerial Councils 6.7 Summary 6.8 Exercises Suggested Readings 6.1 INTRODUCTION Australia, like India and Canada, is both a federal and parliamentary democracy. In 1900 when Australia adopted a federal constitution, there was a history of economic and political independence in the federating colonies. Australia's founding fathers, while trained in the working of British Westminster model, were quite attracted to the American federal model. Thus six self- governing British colonies, while becoming constituent states of the federal system, ensured that the rights of the states would not be subordinated to the central power and there was equal representation in the senate. Accordingly, the constitution provided that the Commonwealth would have only such powers as were expressively conferred upon it, leaving all the residual powers within the exclusive authority of the states. However, from the very beginning there emerged a national sentiment for strengthening and augmenting the central government powers. There came up a gradual expansion of the central government. This was achieved partly by constitutional amendments, partially by High Courts interpretations and to some extent by the consent of states in a formal manner during the two World Wars. -

Office of Profit Under the Crown

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2017–18 14 JUNE 2018 Office of profit under the Crown Professor Anne Twomey, University of Sydney Law School Executive summary • Section 44(iv) of the Constitution provides that a person is incapable of being chosen as a Member of Parliament if he or she holds an ‘office of profit under the Crown’. This is also a ground for disqualification from office for existing members and senators under section 45. There has been considerable uncertainty about what is meant by holding an office of profit under the Crown. • First the person must hold an ‘office’. This is a position to which duties attach of a work-like nature. It is usually, but not always the case, that the office continues to exist independently of the person who holds it. However, a person on the ‘unattached’ list of the public service still holds an office. • Second, it must be an ‘office of profit’. This means that some form of ‘profit’ or remuneration must attach to the office, regardless of whether or not that profit is transferred to the office- holder. Reimbursement of actual expenses does not amount to ‘profit’, but a public servant who is on leave without pay or an office-holder who declines to accept a salary or allowances still holds an office of profit. The source of the profit does not matter. Even if it comes from fees paid by members of the public or other private sources, as long as the profit is attached to the office, that is sufficient. • Third, the office of profit must be ‘under the Crown’. -

Relations Between Chambers in Bicameral Parliaments 121

Relations between Chambers in Bicameral Parliaments 121 III. Relations between Chambers in Bicameral Parliaments 1. Introductory Note by the House of Commons of Canada, June 1991 In any bicameral parliament the two Houses share in the making of legisla- tion, and by virtue both of being constituent parts of the same entity and of this shared function have a common bond or link. The strength or weakness of this link is initially forged by the law regulating the composition, powers and functions of each Chamber, but is tempered by the traditions, practices, the prevailing political, social and economic climate and, indeed, even the personalities which comprise the two Chambers. Given all of these variables and all of the possible mutations and combina- tions of bicameral parliaments in general, no single source could presume to deal comprehensively with the whole subject of relations between the Houses in bicameral parliaments. Instead, the aim of the present notes is to attempt to describe some of the prominent features of relations between the two Houses of the Canadian Parliament with a view to providing a focus for discussion. The Canadian Context The Constitution of Canada provided in clear terms: "There shall be One Parliament for Canada, consisting of the Queen, an Upper House styled the Senate, and the House of Commons." The Senate, which was originally designed to protect the various regional, provincial and minority interests in our federal state and to afford a sober second look at legislation, is an appointed body with membership based on equal regional representation. Normally the Senate is composed of 104 seats which are allotted as follows: 24 each in Ontario, Quebec, the western provinces (6 each for Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia) and the Maritimes (10 each in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick and 4 in Prince Edward Island); six in Newfoundland and one each in the Yukon and Northwest Territories. -

Annual Report 2019

Contents Corporate Profile 2 Corporate Information 4 Our Products 6 Business Overview 13 Financial Highlights 32 CEO’s Statement 33 Management Discussion and Analysis 36 Directors and Senior Management 48 Directors’ Report 56 Corporate Governance Report 74 Independent Auditor’s Report 86 Consolidated Balance Sheet 92 Consolidated Income Statement 94 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 95 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 96 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 97 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 98 Five Years’ Financial Summary 168 02 NEXTEER AUTOMOTIVE GROUP LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Corporate Profile Nexteer Automotive Group Limited (the Company) together with its subsidiaries are collectively referred to as we, us, our, Nexteer, Nexteer Automotive or the Group. Nexteer Automotive is a global leader in advanced steering and driveline systems, as well as advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) and automated driving (AD) enabling technologies. In-house development and full integration of hardware, software and electronics give Nexteer a competitive advantage as a full-service supplier. As a leader in intuitive motion control, our continued focus and drive is to leverage our design, development and manufacturing strengths in advanced steering and driveline systems that provide differentiated and value-added solutions to our customers. We develop solutions that enable a new era of safety and performance for traditional and varying levels of ADAS/AD. Overall, we are making driving safer, more fuel-efficient and fun for today’s world and an automated future. Our ability to seamlessly integrate our systems into automotive original equipment manufacturers’ (OEM) vehicles is a testament to our more than 110-year heritage of vehicle integration expertise and product craftsmanship. -

Supplementary Remarks – Daryl Melham MP

Supplementary remarks – Daryl Melham MP Should British subjects who are not Australian citizens continue to exercise the franchise? In 1984 Australian citizenship become the qualification for enrolment and voting. However, an exception was made for British subjects who were already on the electoral roll, recognising them as a separate class of elector, with grandfathering arrangements put in place to maintain their entitlement to the franchise. The Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) advised that as at 30 September 2008, some 162,928 electors with ‘British subject’ notation remained on the electoral roll.1 Since 1984, three significant events have occurred which provide sufficient reason to reconsider whether grandfathering arrangements that maintain the franchise for British subjects who are not Australian citizens continue to be justified. The first was the passage of the Australia Act 1986, which severed any remaining constitutional links between the Commonwealth and state governments and the United Kingdom. The second was the High Court of Australia’s decision in 1999 in relation to the eligibility of a citizen of another country (in this case the United Kingdom) to be a member of the Commonwealth Parliament. In the view of the High Court, Ms Heather Hill — who was a citizen of the United Kingdom and had been elected to the position of Senator for Queensland at the 1998 federal election— was a subject 1 Australian Electoral Commission, submission 169.6, Annex 3. Note that the national total for electors with British subject notation differs from that in the Australian Electoral Commission’s submission (159,095) due to an error made by the Commission in summing each division and jurisdictions. -

NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No

Edwin Greenslade (Dryblower) Murphy, journalist, 1866-1939, is pictured above. But ‘Dryblower’ was more than a journalist. He wrote verse, satirical verse, amusing verse, verse that soon became an institution in the Coolgardie Miner. It all began at Bulong when a dusty and soiled envelope provided copy paper for the first piece of verse penned and printed between York, WA, and South Australia. Murphy wrote “The Fossicker’s Yarn” to “squash and squelch the objectionable ‘Jackeroo’ (sic) system obtaining on Bayley’s Reward Mine”. “Dryblower” sent the verses to the Coolgardie Miner and a friend sent them to the Sydney Bulletin. The Bulletin published them first, while the Miner “had them in type awaiting issue”. They appeared in the third issue of the Miner. See ANHG 94.4.9 below for Dryblower’s poem, “The Printer”. AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 94 October 2017 Publication details Compiled for the Australian Newspaper History Group by Rod Kirkpatrick, U 337, 55 Linkwood Drive, Ferny Hills, Qld, 4055. Ph. +61-7-3351 6175. Email: [email protected] Contributing editor and founder: Victor Isaacs, of Canberra, is at [email protected] Back copies of the Newsletter and some ANHG publications can be viewed online at: http://www.amhd.info/anhg/index.php Deadline for the next Newsletter: 8 December 2017. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] Ten issues had appeared by December 2000 and the Newsletter has since appeared five times a year. 1—Current Developments: National & Metropolitan 94.1.1 Media-ownership laws updated after 30 years A sweeping media overhaul that the Turnbull government says will deliver the “biggest reform” in nearly 30 years has been hailed by the industry, as small and regional companies win new funding to invest in their newsrooms (Australian, 15 September 2017). -

A “Foreign” Country? Australia and Britain at Empire's End

A “Foreign” Country? Australia and Britain at Empire’s End. Greta Beale A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of B.A. (Advanced)(Hons) in History. University of Sydney October 2011 − Acknowledgements – ____________________________________________________________________________________________ I would like to firstly thank my supervisor Dr. James Curran for his patience, support and for sharing with me his incredible knowledge and passion for Australian political history. Your guidance was invaluable and much appreciated. I would also like to thank the 2011 honours coordinator, Dr. Kirsten McKenzie, for guiding me in the right direction and for her encouraging words. To the staff at Fisher Library, the National Library of Australia and the National Archives of Australia, your assistance in the research stages of the thesis was so helpful, and I thank you for going above and beyond your respective roles. To my family, I thank you for talking me through what sometimes seemed an overwhelming task. To Dad and Sasha, my calming influences, and to Mum, for her patient and precise proof reading, day trips to Canberra, and for listening with genuine interest to my ongoing discussions about the finer details of the Anglo- Australian relationship, many, many thanks. 2 - Contents - _____________________________________________________________________ Acknowledgements 2 Introduction Disentangling From Empire 4 Chapter 1 The Myth of “Civic Britannicus Sum” The United Kingdom Commonwealth Immigration Act 27 Chapter 2 “Austr-aliens” The Commonwealth Immigration Act, 1971. 49 Chapter 3 “Another tie is loosed” The transfer of responsibility for Australia House, 1972. 71 Conclusion 95 Bibliography 106 3 − Introduction − Disentangling from Empire ___________________________________________________________________________________________ In July 1973, the Australian Ambassador to the United States, James Plimsoll, received a personal letter from the retired Australian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, Sir Alexander Downer. -

Constitutional Origins, Structure and Change in Federal Democracies

Commonwealth of Australia Cheryl Saunders Australia’s Constitution was negotiated during the last decade of the nineteenth century and came into force on 1 January 1901. Its federal features were substantially influenced by United States federalism, as then understood. Nevertheless, the Australian Constitution was distinctive from the outset in ways that were recognized during the drafting and that have become more prominent over time. Australia’s Constitution combines United States-style federalism with British institutions of parliamentary responsible government, creating a different dynamic for decision making within and between the spheres of government. The framers of the Constitution initially feared that these two sets of principles would be antagonistic, and indeed, accommodation has not always been easy. More significantly, however, with federalism and responsible government came different approaches to constitutionalism. One involved the limitation of power in an entrenched, written constitution. The other was highly pragmatic, favouring flexibility and efficiency over written constitutional rules. The tension between the two is still reflected in Australian constitutionalism. Those parts of the Constitution that create the legislature and the executive leave considerable discretion to the institutions of government. Attempts to apply constitutional restraints to them, even in the name of protecting democratic principles, have met considerable resistance.1 Few rights are secured through the Constitution; the framers, in the British tradition, assumed that rights could be protected by the Parliament and the common law. Few limits are placed on decision making by the states beyond those necessitated by federalism itself. By contrast, those parts of the Australian Constitution -- namely, allocating power for federal purposes, providing for social and economic union, and establishing the judicature, originally considered an incident of federalism2 -- are taken very seriously. -

Casual Vacancies and the Meek Method

Casual vacancies and the Meek method I.D. Hill are not looked at until the fates of earlier preferences [email protected] have been definitely determined. When recounting, later preferences will have been looked at, and acted upon, in making the initial count and that cannot be 1 Introduction undone. Provided that voters can be assured that it cannot happen on the initial count, the thought that If a casual vacancy occurs in a body that has been a casual vacancy could occur later and need to be elected by STV, caused, for example, by an elected dealt with, is rather unlikely to worry anyone much. member resigning, there is a difficulty because to hold a by-election for just the one vacant seat would, There remain some problems: (1) if the voting usually, result in the dominant party (or other in- pattern has been published, as I believe it should terest group) gaining the seat, whereas the vacancy be, it is possible to determine with certainty who a may have arisen by the resignation of a candidate replacement will be and, in a party situation, that from a minority group. The ideal solution, in many could lead to pressure on someone to resign; (2) in ways, would be that of Thomas Wright Hill’s 1819 a party situation, there may be no spare candidate of version of STV [1, 2] in which a substitute would be the same party. This could be an advantage, though, elected only by those electors who had, in the first in that it might persuade parties to offer more candi- place, elected the resigning candidate – but that so- dates in the first place in case of such an eventuality, lution is not possible in these days of secret voting. -

The Grounds & Facts

THE GROUNDS & FACTS GROUNDS & FACT From:- 1 to 82 1. Queen Elizabeth the Second Sovereign Head of the Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem Apparently Queen Elizabeth the Second is the sovereign head of the Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem and as such the Constitution of the State of Victoria is fraudulent in that a United Kingdom Monarch purportedly a Protestant Monarch is the sovereign head of an International Masonic Order whose allegiance is to the Bishop of Rome. 2. Statute by Henry VIII 1540 Banning the Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem Specific Points in the Statute of 1540 A. Knights of the Rhodes B. Knights of St John C. Friars of the Religion of St John of Jerusalem in England and Ireland D. Contrary to the duty of their Allegiance E. Sustained and maintained the usurped power and authority of the Bishop of Rome F. Adhered themselves to the said Bishop being common enemy to the King Our Sovereign Lord and to His realm G. The same Bishop to be Supreme and Chief Head of Christ’s Church H. Intending to subvert and overthrow the good and Godly laws and statutes of His realm I. With the whole assent and consent of the Realm, for the abolishing, expulsing and utter extinction of the said usurped power and authority 1 3. The 1688 Bill of Rights (UK) A. This particular statute came into existence after the trial of the 7 Bishops in the House of Lords, the jury comprised specific members of the House of Lords -The King v The Seven Bishops B. -

Vol. 5 No. 2 This Article Is from *Sikh Research Journal*, the Online Peer-Reviewed Journal of Sikh and Punjabi Studies

Vol. 5 No. 2 This article is from *Sikh Research Journal*, the online peer-reviewed journal of Sikh and Punjabi Studies Sikh Research Journal *Vol. 5 No. 2 Published: Fall 2020. http://sikhresearchjournal.org http://sikhfoundation.org Sikh Research Journal Volume 5 Number 2 Fall 2020 Contents Articles Eleanor Nesbitt Ghost Town and The Casual Vacancy: 1 Sikhs in the Writings of Western Women Novelists Sujinder Singh Sangha The Political Philosophy of Guru 23 Nanak and Its Contemporary Relevance Arvinder Singh, Building an Open-Source Nanakshahi 40 Amandeep Singh, Calendar: Identity and a Spiritual and Amarpreet Singh, Computational Journey Harvinder Singh, Parm Singh Victoria Valetta Mental Health in the Guru Granth 51 Sahib: Disparities between Theology and Society Harleen Kaur, Sikhs as Implicated Subjects in the 68 prabhdeep singh kehal United States: A Reflective Essay (ਿਵਚਾਰ) on Gurmat-Based Interventions in the Movement for Black Lives Book Colloquium Faith, Gender, and Activism in the 87 Punjab Conflict: The Wheat Fields Still Whisper (Mallika Kaur) Navkiran Kaur Chima Intersection of Faith, Gender, and 87 Activism: Challenging Hegemony by Giving “Voice” to the Victims of State Violence in Punjab Shruti Devgan The Punjab Conflict Retold: 91 Extraordinary Suffering and Everyday Resistance Harleen Kaur The Potency of Sikh Memory: Time 96 Travel and Memory Construction in the Wake of Disappearance Sasha Sabherwal Journeying through Mallika Kaur’s 100 Faith, Gender, and Activism in the Punjab Conflict Mallika Kaur Book Author’s Reflective Response to 105 Review Commentaries In Memoriam Jugdep S. Chima Remembrance for Professor Paul 111 Wallace (1931-2020) Sikh Research Journal, Vol.