Design-Build Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Project Manager Real Estate Development Job Description, Full-Time

Project Manager Real Estate Development Job Description, Full-time Organizational Background: Founded in 1995, East LA Community Corporation (“ELACC”) mission is to advocate for economic and social justice in Boyle Heights and Unincorporated East Los Angeles by building grassroots leadership, self- sufficiency and access to economic development opportunities for low and moderate income families and to use its development expertise to strengthen existing community infrastructure in communities of color by developing and persevering neighborhood assets. Project Manager ELACC seeks an individual who is highly motivated and organized. Applicant should have either a Bachelor’s degree and five years of experience in affordable housing development or a Master’s degree and 2-3 years of experience in affordable housing development. The Project Manager will work in a team environment with ELACC’S Real Estate Development, Finance, and Asset Management departments. Under the supervision of the Director of Real Estate Development, the Project Manager, shall be able to demonstrate experience in working on acquisition projects, by assisting to identify properties available for development within ELACC’s service area and submitting responses to RFP/Q’s. The Project Manager shall be able to coordinate all aspects of pre-development, including applying for and securing financing, preparation of proformas, entitlements, oversight of design professionals for the purpose of obtaining building permits, and construction loan closings from numerous funding sources. The Project Manager shall demonstrate competency in construction administration and shall be able to take a development to construction completion and into operations. Candidates should be able to demonstrate this experience on multiple specific developments. -

Using Experience Design to Drive Institutional Change, by Matt Glendinning

The Monthly Recharge - November 2014, Experience Design Designing Learning for School Leaders, by Carla Silver Using Experience Design to Drive Institutional Change, by Matt Glendinning Designing the Future, by Brett Jacobsen About L+D Designing Learning for School Leadership+Design is a nonprofit Leaders organization and educational Carla Robbins Silver, Executive Director collaborative dedicated to creating a new culture of school leaders - empathetic, creative, collaborative Dear Friends AND Designers: and adaptable solution-makers who can make a positive difference in a The design industry is vast and wonderful. In his book, Design: rapidly changing world. Creation of Artifacts in Society, Karl Ulrich, professor at Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, includes an We support creative and ever-growing list of careers and opportunities in design. They innovative school leadership at range form the more traditional and known careers - architecture the individual and design, product design, fashion design, interior design - to organizational level. possibilities that might surprise you - game design, food design, We serve school leaders at all news design, lighting and sound design, information design and points in their careers - from experience design. Whenever I read this list, I get excited - like teacher leaders to heads of jump-out-of-my-seat excited. I think about the children in all of our school as well as student schools solving complex problems, and I think about my own leaders. children, and imagine them pursuing these careers as designers. We help schools design strategies for change, growth, Design is, according to Ulrich, "conceiving and giving form to and innovation. -

Design Piracy: the Extensive Impact of a Fashion Knockoff

On the Monetary Impact of Fashion Design Piracy Gil Appel Marshall School of Business, University of Southern California [email protected] Barak Libai Arison School of Business, Interdisciplinary Center (IDC), Herzliya [email protected] Eitan Muller Stern School of Business, New York University Arison School of Business, Interdisciplinary Center (IDC), Herzliya [email protected] July 2017 The authors would like to thank Roland Rust, Senior Editor and reviewers, On Amir, Michael Haenlein, Liraz Lasry, Irit Nitzan, Raphael Thomadsen, the participants of the Marketing Science and EMAC conferences and the participants of the seminars of the business schools at University of California at Davis, the University of California at San Diego, and Stanford University for a number of helpful comments and suggestions. On the Monetary Impact of Fashion Design Piracy Abstract Whether to legally protect original fashion designs against design piracy (“knockoffs”) is an ongoing debate among legislators, industry groups, and legal academic circles, yet to-date this discussion has not utilized marketing knowledge and formal approaches. We combine data collected on the growth of fashion items, price markups, and industry statistics, to create a formal analysis of the essential questions in the base of the debate. We distinguish between three effects: Acceleration, whereby the presence of a pirated design increases the awareness of the design, and thus might have a positive effect on the growth of the original; Substitution, which represents the loss of sales due to consumers who would have purchased the original design, yet instead buy the knockoff; and the loss due to Overexposure of the design that follows the loss of uniqueness due to the design becoming too popular, causing some consumer not to adopt the design or stop using it. -

Transformational Information Design 35

Petra Černe Oven & Cvetka Požar (eds.) ON INFORMATION DESIGN Edited by Petra Černe Oven and Cvetka Požar Ljubljana 2016 On Information Design Edited by Petra Černe Oven and Cvetka Požar AML Contemporary Publications Series 8 Published by The Museum of Architecture and Design [email protected], www.mao.si For the Museum of Architecture and Design Matevž Čelik In collaboration with The Pekinpah Association [email protected], www.pekinpah.org For the Pekinpah Association Žiga Predan © 2016 The Museum of Architecture and Design and authors. All rights reserved. Photos and visual material: the authors and the Museum for Social and Economic Affairs (Gesellschafts- und Wirtschaftsmuseum), Vienna English copyediting: Rawley Grau Design: Petra Černe Oven Typefaces used: Vitesse and Mercury Text G2 (both Hoefler & Frere-Jones) are part of the corporate identity of the Museum of Architecture and Design. CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 7.05:659.2(082)(0.034.2) ON information design [Elektronski vir] / Engelhardt ... [et al.] ; edited by Petra Černe Oven and Cvetka Požar ; [photographs authors and Austrian Museum for Social and Economic Affairs, Vienna]. - El. knjiga. - Ljubljana : The Museum of Architecture and Design : Društvo Pekinpah, 2016. - (AML contemporary publications series ; 8) ISBN 978-961-6669-26-9 (The Museum of Architecture and Design, pdf) 1. Engelhardt, Yuri 2. Černe Oven, Petra 270207232 Contents Petra Černe Oven Introduction: Design as a Response to People’s Needs (and Not People’s Needs -

Construction Project Management Handbook, F T a Report No. 0015

Construction Project Management Handbook MARCH 2012 FTA Report No. 0015 Federal Transit Administration PREPARED BY Kam Shadan, P.E. Gannett Fleming, Inc. COVER PHOTO Edwin Adilson Rodriguez, Federal Transit Administration DISCLAIMER This document is intended as a technical assistance product. It is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. The United States Government does not endorse products of manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. This Handbook is intended to be a general reference document for use by public transportation agencies responsible for the management of capital projects involving construction of a transit facility or system. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government and the Contractor, Gannett Fleming, Inc., assume no liability for the contents or use thereof. The United States Government does not endorse manufacturers or products. Trade or manufacturers names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. Construction Project Management Handbook MARCH 2012 FTA Report No. 0015 PREPARED BY Kam Shadan, P.E. Gannett Fleming, Inc. 591 Redwood Highway Mill Valley, CA 94941-3064 http://www.gannettfleming.com SPONSORED -

CAD Usage in Modern Engineering and Effects on the Design Process

CAD Usage in Modern Engineering and Effects on the Design Process A Research Paper submitted to the Department of Engineering and Society Presented to the Faculty of the School of Engineering and Applied Science University of Virginia • Charlottesville, Virginia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Science, School of Engineering Pascale Starosta Spring, 2021 On my honor as a University Student, I have neither given nor received unauthorized aid on this assignment as defined by the Honor Guidelines for Thesis-Related Assignments 5/11/2021 Signature __________________________________________ Date __________ Pascale Starosta Approved __________________________________________ Date __________ Sean Ferguson, Department of Engineering and Society CAD Usage in Modern Engineering and Effects on the Design Process Computer-aided design (CAD) is widely used by engineers in the design process as companies transition from physical modeling and designing to an entirely virtual environment. Interacting with computers instead of physical models forces engineers to change their critical thinking skills and learn new techniques for designing products. To successfully use CAD programs, engineering education programs must also adapt in order to prepare students for the working world as it transitions to primarily computer design work. These adjustments over time, as CAD becomes the dominant method for designing in the engineering field, ultimately have effects on the products engineers are creating and how they are brainstorming and moving through the design process. Studies and surveys can be conducted on current engineering students as well as professional engineers to determine how they interact with CAD differently from physical models, and how computer software can be improved to make the design process more intuitive and efficient. -

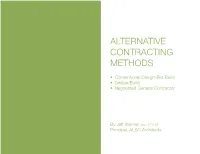

Alternative Contracting Methods

ALTERNATIVE CONTRACTING METHODS • Conventional Design-Bid-Build • Design/Build • Negotiated General Contractor By Jeff Warner, AIA, LEED AP Principal, ALSC Architects CONVENTIONAL DESIGN-BID-BUILD The most traditional method of delivery of a construction PROS project is where the Architect, after selection by the Client, 1. Costs may be lower due to competition. totally completes the design documents which are then 2. Project design is typically complete prior to start of distributed to General Contractors for bidding. Usually, the construction. low bidder is selected to construct the project and enters 3. Owner receives a single lump sum proposal for the entire into a lump sum type contract agreement directly with the project not subject to cost escalation. Owner. During construction, the Architect typically maintains 4. This approach conforms most directly to public bidding a strong administrative role and is the focal point of most laws. communication on the project between the Contractor and Owner. While proponents of this method of contracting feel that CONS the lowest overall initial costs are obtained through pure 1. If bids exceed budget, the project may require re-design. competitive bidding, an adversarial relationship between 2. Difficult to fast-track or pre-order materials, resulting in principal parties can develop; making the administration of later Owner occupancy. changes more difficult, time consuming and costly. Perhaps 3. The General Contractor may be in an adversarial the biggest potential problem with this approach to a major, relationship with the Owner and Architect/Engineer. complex construction project is that the Owner does not 4. Prices for change order work are typically higher and obtain a firm handle on construction costs until the project has more difficult to control. -

Information Scaffolding: Application to Technical Animation by Catherine

Information Scaffolding: Application to Technical Animation By Catherine Claire Newman a dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in ENGINEERING – MECHANICAL ENGINEERING in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in Charge: Professor Alice Agogino, Chair Professor Dennis K Lieu Professor Michael Buckland FALL, 2010 Information Scaffolding: Application to Technical Animation Copyright © 2010 Catherine Newman i if you can help someone turn information into knowledge, if you can help them make sense of the world, you win. --- john battelle ii Abstract Information Scaffolding: Application to Technical Animation by Catherine C. Newman Doctor of Philosophy in Mechanical Engineering University of California, Berkeley Professor Alice Agogino, Chair Information Scaffolding is a user-centered approach to information design; a method devised to aid “everyday” authors in information composition. Information Scaffolding places a premium on audience-centered documents by emphasizing the information needs and motivations of a multimedia document's intended audience. The aim of this method is to structure information in such a way that an intended audience can gain a fuller understanding of the information presented and is able to incorporate knowledge for future use. Information Scaffolding looks to strengthen the quality of a document’s impact both on the individual and on the broader, ongoing disciplinary discussion, by better couching a document’s contents in a manner relevant to the user. Thus far, instructional research design has presented varying suggested guidelines for the design of multimedia instructional materials (technical animations, dynamic computer simulations, etc.), primarily do’s and don’ts. -

Change Orders Ordeal: the Output of Project Disintegration

International Journal of Business, Humanities and Technology Vol. 2 No. 1; January 2012 Change Orders Ordeal: The Output of Project Disintegration Roberto Soares, Ph.D., D.Sc., AIC, PE Assistant Professor College of Computing, Engineering and Construction University of North Florida Jacksonville, Florida United States of America Abstract Change orders are one of the most controversial issues in construction contracts and require successful negotiations to avoid claims and possible litigation. Contractors, owners and architects behave differently when dealing with change orders. The aim of this paper is to demonstrate that change orders are the natural result of the disintegration of design and construction, which started in the US in 1893 with a Congressional Act formally separating the design and construction phases of a capital project .Delivery methods such as Design-Build (DB) and Construction Management at Risk (CMR), which are designed to mend the missing integration of design and construction and, consequently, eliminate the existence of change order conflict are proposed to recover the level of integration that existed at the time of the master builder. Key words: change orders, project integration, design-build, delivery methods 1. Introduction Change orders in construction are one of the most controversial issues to manage and a challenge to project management to satisfactorily resolve any change in order to avoid claims. Any construction contract is signed under the principle of “good faith,” which means that the parties will trust each other to perform according to the contract and that the contract is fair with no intention of taking advantage of the parties during the life of the contract. -

SELECTED TOPICS in NOVEL OPTICAL DESIGN by Yufeng

Selected Topics in Novel Optical Design Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Yan, Yufeng Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 03/10/2021 19:21:21 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/636613 SELECTED TOPICS IN NOVEL OPTICAL DESIGN by Yufeng Yan ____________________________ Copyright © Yufeng Yan 2019 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the JAMES C. WYANT COLLEGE OF OPTICAL SCIENCES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2019 2 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to first thank my parents in China for their support that encouraged me to pursue both bachelor’s, master’s and doctorate degree abroad. I would also like to thank my girlfriend Jie Feng for her strong support and being the first reader of each chapter of this dissertation. I am very grateful to my adviser, Dr. Jose Sasian. This project would not have been possible without his constant support and mentoring. I would also like to acknowledge the members of my committee, Dr. Rongguang Liang and Dr. Jim Schwiegerling, who took their time to review this dissertation and gave me valuable suggestions. In addition, I would like to thank Zemax for giving me permission to use their software for designing and evaluating the optical systems in this project. -

Building Information Modeling (BIM) Standard & Guide

Building Information Modeling (BIM) Standard & Guide Version 1 – December 2014 No portion of this work may be reproduced without the express written permission of the copyright holders. All rights reserved by Florida International University. ` FIU BIM Specification ‐ Final 120814 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Intent: ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 BIM Goals: ................................................................................................................................................. 4 BIM Uses: .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Capital planning support: ...................................................................................................................... 6 Pre‐Design and Programming ............................................................................................................... 6 Site Conditions ‐ Existing Conditions and New Construction ............................................................... 6 Architectural Model ‐ Spatial and Material Design Models .................................................................. 7 Space and Program Validation ............................................................................................................. -

SENIOR CONSTRUCTION PROJECT MANAGER DEFINITION to Plan

CONSTRUCTION PROJECT MANAGER/ SENIOR CONSTRUCTION PROJECT MANAGER DEFINITION To plan, organize, direct and supervise public works construction projects and inspection operations within the Engineering Division. Manage the planning, execution, supervision and coordination of technical aspects of field engineering assignments including development and maintenance of schedules, contracts, budgets, means and methods. Exercise discretion and independent judgment with respect to assigned duties. DISTINGUISHING CHARACTERISTICS The Senior Construction Project Manager position is an advance journey level professional position and is distinguished from the Construction Project Manager by higher level performance and depth of involvement in the management of construction projects, and participation in the long-range planning and administrative functions within the Engineering Department. SUPERVISION RECEIVED AND EXERCISED Receives general direction from Principal Civil Engineer or other supervisory staff. Exercises direct supervision over construction inspection staff, outside contractors, and/or other paraprofessional staff, as assigned. EXAMPLE OF DUTIES: The following are typical illustrations of duties encompassed by the job class, not an all inclusive or limiting list: ESSENTIAL JOB FUNCTIONS Plan, organize, coordinate, and direct the work of construction projects within the Engineering Division to include the construction of streets, storm drains, parks, traffic control systems, water and wastewater facilities and other Capital Improvement Program (CIP) projects. Provide direction and management for multiple large and complex public works construction and CIP projects. Ensure on-schedule completion within budget in accordance with contract documents and City, State and Federal requirements. 1 Construction Project Manager/ Senior Construction Project Manager Perform difficult and complex field assignments involving the development, execution, supervision, and coordination of all technical aspects of a construction project.