Sinhala-Ness and Sinhala Nationalism, Michael Roberts, 2001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dammika Ranatunga Prospects Or Finances

Shipmanagement: How I Work projects that did not improve the SLPA’s Dammika Ranatunga prospects or finances. Dammika was Chairman of Sri Lanka Ports Authority brought in to cleanse the Augean stables. Although Ranatunga steers clear of mentioning his predecessor by name, or By Shirish Nadkarni “I have to wear that belt whenever directly denigrating the projects with which I walk. In fact, I will have to shortly the former Chairman was associated, it hen Dammika Ranatunga undergo surgery for a slipped disc in the is a matter of public record that Priyath stands up slowly and sacro-lumbar region,” says the 53-year-old Bandu Wickrema, who was Rajapaksa’s awkwardly from behind Dammika, who is also an international nominee to what is essentially a political hisW massive desk at the Sri Lanka Ports cricketer, having represented Sri Lanka appointment, left the SLPA in disgrace. Authority (SLPA) headquarters to greet in two Tests in 1989 and four one-day What’s more, an investigation was you, you cannot escape the feeling that internationals in 1990, as a right-hand carried out into Wickrema’s personal you are in the presence of Sri Lanka’s middle-order batsman and occasional finances for allegedly having amassed most successful cricket captain, who offbreak bowler. wealth disproportionate to his known delivered the 1996 World Cup to his sources of income. He and his wife were delirious countrymen. questioned in mid-March last year by Indeed, the resemblance between the Central Intelligence Department Arjuna Ranatunga and his equally stocky, over alleged money laundering in deals portly elder brother Dammika is startling, When I took over as done by Wickrema with, among others, and seems to have got accentuated with Chairman, it took me China Communications Construction every passing year. -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Eighth Parliament - First Session) No. 70. ] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Wednesday, May 18, 2016 at 1.00 p.m. PRESENT : Hon. Karu Jayasuriya, Speaker Hon. Thilanga Sumathipala, Deputy Speaker and Chairman of Committees Hon. Selvam Adaikkalanathan, Deputy Chairman of Committees Hon. Ranil Wickremesinghe, Prime Minister and Minister of National Policies and Economic Affairs Hon. Wajira Abeywardana, Minister of Home Affairs Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Amunugama, Minister of Special Assignment Hon. Gayantha Karunatileka, Minister of Parliamentary Reforms and Mass Media and the Chief Government Whip Hon. Ravi Karunanayake, Minister of Finance Hon. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam, Minister of Education Hon. Lakshman Kiriella, Minister of Higher Education and Highways and the Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. Daya Gamage, Minister of Primary Industries Hon. Dayasiri Jayasekara, Minister of Sports Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation Hon. Navin Dissanayake, Minister of Plantation Industries Hon. S. B. Dissanayake, Minister of Social Empowerment and Welfare Hon. S. B. Nawinne, Minister of Internal Affairs, Wayamba Development and Cultural Affairs Hon. Harin Fernando, Minister of Telecommunication and Digital Infrastructure Hon. A. D. Susil Premajayantha, Minister of Science, Technology and Research Hon. Sajith Premadasa, Minister of Housing and Construction Hon. R. M. Ranjith Madduma Bandara, Minister of Public Administration and Management Hon. Anura Priyadharshana Yapa, Minister of Disaster Management ( 2 ) M. No. 70 Hon. Sagala Ratnayaka, Minister of Law and Order and Southern Development Hon. Arjuna Ranatunga, Minister of Ports and Shipping Hon. Patali Champika Ranawaka, Minister of Megapolis and Western Development Hon. Chandima Weerakkody, Minister of Petroleum Resources Development Hon. Malik Samarawickrama, Minister of Development Strategies and International Trade Hon. -

Minutes of Parliament for 08.01.2019

(Eighth Parliament - Third Session) No. 14. ] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Tuesday, January 08, 2019 at 1.00 p.m. PRESENT : Hon. J. M. Ananda Kumarasiri, Deputy Speaker and the Chair of Committees Hon. Selvam Adaikkalanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Ranil Wickremesinghe, Prime Minister and Minister of National Policies, Economic Affairs, Resettlement & Rehabilitation, Northern Province Development, Vocational Training & Skills Development and Youth Affairs Hon. (Mrs.) Thalatha Atukorale, Minister of Justice & Prison Reforms Hon. Wajira Abeywardana, Minister of Internal & Home Affairs and Provincial Councils & Local Government Hon. John Amaratunga, Minister of Tourism Development, Wildlife and Christian Religious Affairs Hon. Gayantha Karunatileka, Minister of Lands and Parliamentary Reforms and Chief Government Whip Hon. Ravi Karunanayake, Minister of Power, Energy and Business Development Hon. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam, Minister of Education Hon. Lakshman Kiriella, Minister of Public Enterprise, Kandyan Heritage and Kandy Development and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. Daya Gamage, Minister of Labour, Trade Union Relations and Social Empowerment Hon. Palany Thigambaram, Minister of Hill Country New Villages, Infrastructure & Community Development Hon. Navin Dissanayake, Minister of Plantation Industries Hon. Gamini Jayawickrama Perera, Minister of Buddhasasana & Wayamba Development Hon. Harin Fernando, Minister of Telecommunication, Foreign Employment and Sports Hon. R. M. Ranjith Madduma Bandara, Minister of Public Administration & Disaster Management Hon. Rishad Bathiudeen, Minister of Industry & Commerce, Resettlement of Protracted Displaced Persons and Co-operative Development ( 2 ) M. No. 14 Hon. Tilak Marapana, Minister of Foreign Affairs Hon. Sagala Ratnayaka, Minister of Ports & Shipping and Southern Development Hon. Arjuna Ranatunga, Minister of Transport & Civil Aviation Hon. Patali Champika Ranawaka, Minister of Megapolis & Western Development Hon. -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Eighth Parliament - First Session) No. 134. ] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Tuesday, December 06, 2016 at 9.30 a. m. PRESENT : Hon. Karu Jayasuriya, Speaker Hon. Thilanga Sumathipala, Deputy Speaker and Chairman of Committees Hon. Ranil Wickremesinghe, Prime Minister and Minister of National Policies and Economic Affairs Hon. (Mrs.) Thalatha Atukorale, Minister of Foreign Employment Hon. Wajira Abeywardana, Minister of Home Affairs Hon. John Amaratunga, Minister of Tourism Development and Christian Religious Affairs and Minister of Lands Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Development Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Amunugama, Minister of Special Assignment Hon. Gayantha Karunatileka, Minister of Parliamentary Reforms and Mass Media and Chief Government Whip Hon. Ravi Karunanayake, Minister of Finance Hon. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam, Minister of Education Hon. Lakshman Kiriella, Minister of Higher Education and Highways and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. Mano Ganesan, Minister of National Co-existence, Dialogue and Official Languages Hon. Daya Gamage, Minister of Primary Industries Hon. Dayasiri Jayasekara, Minister of Sports Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation Hon. Palany Thigambaram, Minister of Hill Country New Villages, Infrastructure and Community Development Hon. Duminda Dissanayake, Minister of Agriculture Hon. Navin Dissanayake, Minister of Plantation Industries Hon. S. B. Dissanayake, Minister of Social Empowerment and Welfare ( 2 ) M. No. 134 Hon. S. B. Nawinne, Minister of Internal Affairs, Wayamba Development and Cultural Affairs Hon. Gamini Jayawickrama Perera, Minister of Sustainable Development and Wildlife Hon. Harin Fernando, Minister of Telecommunication and Digital Infrastructure Hon. A. D. Susil Premajayantha, Minister of Science, Technology and Research Hon. Sajith Premadasa, Minister of Housing and Construction Hon. -

INSIDE: Financial Review Sampanthan Holds AB Foundation Proxy for LTTE - Keheliya by Harischandra “We Know There Are Gunaratna Only 130,000 IDP’S

The Island Page Three Thursday 19th February, 2009 ! Leisure Land News ! ! World view INSIDE: Financial Review Sampanthan holds AB Foundation proxy for LTTE - Keheliya by Harischandra “We know there are Gunaratna only 130,000 IDP’s. Perhaps Sampanthan has launched Defence Minister a problem with his arith- Keheliya Rambukwella metic,” he quipped. by Shamindra Ferdinando burden. attack the ruling coalition. yesterday accused Tamil “His comments are Among the invitees Ms Sunethra Bandaranaike, UPFA National Alliance (TNA) totally unfounded, base- Assisting the poor is not the exclu- present on the occasion MP Arjuna Ranatunga, UNP MP parliamentary leader R. less and irresponsible. A sive responsibility of a government, were Business tycoon Sarathchandra Rajakaruna, Sampanthan of holding a Keheliya Sambandan senior parliamentarian former President Chandrika Harry Jayawardene, Professor Carlo Fonseka and Upul brief for the LTTE and in the calibre of Kumaratunga said at the launch of one of the closest asso- Mahendra Rajapaksa, Chairman of making a vain attempt to whitewash ter- Sampanthan should have been more Anura Bandaranaike foundation at ciates of the late the Attanagalle Pradeshiya Sabha rorism. realistic when making statements of the Naritasan Hall, Ranpokunugama, Bandaranaike and had been present on the occasion. He was responding to statement by this nature,” he said. Nittambuwa, last week. Chandrika Mrs. Pam Cooray, the Kumaratunga said that the Sampanthan at a news conference held The impediment that the govern- She said that the -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Eighth Parliament - First Session ) No . 233 . ] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Monday, December 11, 2017 at 9.30 a. m. PRESENT ::: Hon. Karu Jayasuriya, Speaker Hon. Thilanga Sumathipala, Deputy Speaker and Chairman of Committees Hon. Selvam Adaikkalanathan, Deputy Chairman of Committees Hon. Wajira Abeywardana, Minister of Home Affairs Hon. John Amaratunga, Minister of Tourism Development and Christian Religious Affairs Hon. Gayantha Karunatileka, Minister of Lands and Parliamentary Reforms and the Chief Government Whip Hon. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam, Minister of Education Hon. Lakshman Kiriella, Minister of Higher Education and Highways and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. Duminda Dissanayake, Minister of Agriculture Hon. Navin Dissanayake, Minister of Plantation Industries Hon. S. B. Nawinne, Minister of Internal Affairs, Wayamba Development and Cultural Affairs Hon. Gamini Jayawickrama Perera, Minister of Sustainable Development and Wildlife and Minister of Buddhasasana Hon. A. D. Susil Premajayantha, Minister of Science, Technology and Research Hon. Rishad Bathiudeen, Minister of Industry and Commerce Hon. Tilak Marapana, Minister of Development Assignments and Minister of Foreign Affairs Hon. Arjuna Ranatunga, Minister of Petroleum Resources Development Hon. Malik Samarawickrama, Minister of Development Strategies and International Trade Hon. Mangala Samaraweera, Minister of Finance and Mass Media Hon. Mahinda Samarasinghe, Minister of Ports and Shipping ( 2 ) M. No. 233 Hon. W. D. J. Senewiratne, Minister of Labour, Trade Union Relations and Sabaragamu Development Hon. (Dr.) Rajitha Senaratne, Minister of Health, Nutrition and Indigenous Medicine Hon. D. M. Swaminathan, Minister of Prison Reforms, Rehabilitation, Resettlement and Hindu Religious Affairs Hon. Rauff Hakeem, Minister of City Planning and Water Supply Hon. Field Marshal Sarath Fonseka, Minister of Regional Development Hon. -

Minutes of Parliament for 23.01.2020

(Eighth Parliament - Fourth Session ) No . 7. ]]] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Thursday, January 23, 2020 at 10.30 a.m. PRESENT ::: Hon. J. M. Ananda Kumarasiri, Deputy Speaker and the Chair of Committees Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Transport Service Management and Minister of Power & Energy Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena, Minister of Foreign Relations and Minister of Skills Development, Employment and Labour Relations and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. S. M. Chandrasena, Minister of Environment and Wildlife Resources and Minister of Lands & Land Development Hon. (Dr.) Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Plantation Industries and Export Agriculture Hon. Johnston Fernando, Minister of Roads and Highways and Minister of Ports & Shipping and Chief Government Whip Hon. Prasanna Ranatunga, Minister of Industrial Export and Investment Promotion and Minister of Tourism and Civil Aviation Hon. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardena, State Minister of Irrigation and Rural Development Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna, State Minister of Public Management and Accounting Hon. Mahindananda Aluthgamage, State Minister of Power Hon. Duminda Dissanayake, State Minister of Youth Affairs Hon. S. B. Dissanayake, State Minister of Lands and Land Development Hon. Wimalaweera Dissanayaka, State Minister of Wildlife Resources Hon. Vasudeva Nanayakkara, State Minister of Water Supply Facilities Hon. Susantha Punchinilame, State Minister of Small & Medium Enterprise Development Hon. A. D. Susil Premajayantha, State Minister of International Co -operation Hon. Tharaka Balasuriya, State Minister of Social Security Hon. C. B. Rathnayake, State Minister of Railway Services Hon. Nimal Lanza, State Minister of Community Development ( 2 ) M. No. 7 Hon. Gamini Lokuge, State Minister of Urban Development Hon. Janaka Wakkumbura, State Minister of Export Agriculture Hon. Vidura Wickramanayaka, State Minister of Agriculture Hon. -

IN PURSUIT of HEGEMONY: Politics and State Building in Sri Lanka

IN PURSUIT OF HEGEMONY: Politics and State Building in Sri Lanka Shyamika Jayasundara-Smits This dissertation is part of the Research Programme of Ceres, Research School for Resource Studies for Development. © Shyamika Jayasundara-Smits 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the author. Printed in The Netherlands. ISBN 978-94-91478-12-3 IN PURSUIT OF HEGEMONY: Politics and State Building in Sri Lanka OP ZOEK NAAR HEGEMONIE: Politiek en staatsvorming in Sri Lanka Thesis to obtain the degree of Doctor from the Erasmus University Rotterdam by command of the Rector Magnificus Professor dr H.G. Schmidt and in accordance with the decision of the Doctorate Board The public defence shall be held on 23 May 2013 at 16.00 hrs by Seneviratne Mudiyanselage Shyamika Jayasundara-Smits born in Colombo, Sri Lanka Doctoral Committee Promotor Prof.dr. M.A.R.M. Salih Other Members Prof.dr. N.K. Wickramasinghe, Leiden University Prof.dr. S.M. Murshed Associate professor dr. D. Zarkov Co-promotor Dr. D. Dunham Contents List of Tables, Diagrams and Appendices viii Acronyms x Acknowledgements xii Abstract xv Samenvatting xvii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Literature Review 1 1.1.1 Scholarship on Sri Lanka 4 1.2 The Setting and Justification 5 1.2.1 A Statement of the Problem 10 1.3 Research Questions 13 1.4 Central Thesis Statement 14 1.5 Theories and concepts 14 1.5.1 -

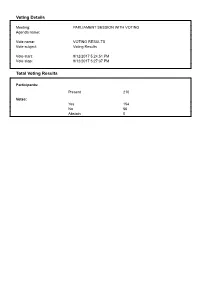

Voting Details Total Voting Results

Voting Details Meeting: PARLIAMENT SESSION WITH VOTING Agenda name: Vote name: VOTING RESULTS Vote subject: Voting Results Vote start: 9/12/2017 5:24:51 PM Vote stop: 9/12/2017 5:27:37 PM Total Voting Results Participants: Present 210 Votes: Yes 154 No 56 Abstain 0 Individual Voting Results GOVERNMENT SIDE G 001. Mangala Samaraweera Yes G 002. S.B. Dissanayake Yes G 003. Nimal Siripala de Silva Yes G 004. Gamini Jayawickrama Perera Yes G 005. John Amaratunga Yes G 006. Lakshman Kiriella Yes G 007. Ranil Wickremesinghe Yes G 009. Gayantha Karunatileka Yes G 010. W.D.J. Senewiratne Yes G 011. Sarath Amunugama Yes G 012. Rauff Hakeem Yes G 013. Rajitha Senaratne Yes G 014. Rishad Bathiudeen Yes G 015. Kabir Hashim Yes G 016. Sajith Premadasa Yes G 017. Malik Samarawickrama Yes G 018. Mano Ganesan Yes G 019. Anura Priyadharshana Yapa Yes G 020. Ven. Athuraliye Rathana Thero Yes G 021. Thilanga Sumathipala Yes G 022. A.D. Susil Premajayantha Yes G 023.Tilak Marapana Yes G 024. Mahinda Samarasinghe Yes G 025. Wajira Abeywardana Yes G 026. S.B. Nawinne Yes G 028. Patali Champika Ranawaka Yes G 029. Mahinda Amaraweera Yes G 030. Navin Dissanayake Yes G 031. Ranjith Siyambalapitiya Yes G 032. Duminda Dissanayake Yes G 033. Wijith Wijayamuni Zoysa Yes G 034. P. Harrison Yes G 035. R.M. Ranjith Madduma Bandara Yes G 036. Arjuna Ranatunga Yes G 037. Palany Thigambaram Yes G 038. Chandrani Bandara Yes G 039. Thalatha Atukorale Yes G 040. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam Yes G 041. -

PR-English Jaffana Airport

High Commission of India Colombo Press Release Inauguration of Jaffna International Airport and Commencement of short-haul flights between Chennai and Jaffna operated by Alliance Air India-Sri Lanka relation touches the sky! President ofSri Lanka, H.E. Maithripala Sirisenainaugurated the Jaffna International Airport today. Prime Minister of Sri Lanka Hon. Ranil Wickremesinghe was also present. The inaugural flight with Indian dignitaries landed in Jaffna airport from Chennai to mark the historic occasion.The ATR72-600 short-haul flight was operated by Alliance Air, a subsidiary of Air India. This is Alliance Air’s first international flight. 2. Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation of Sri Lanka, Hon. Arjuna Ranatunga, several other Ministers and Members of Parliament, Governor, Northern Province, Hon. Dr. Suren Raghavan, High Commissioner of India to Sri Lanka, H.E. Taranjit Singh Sandhu, CMD, Air India, Mr. Ashwani Lohani, CEO, Alliance Air, Mr. C. S. Subbiah, Consul General of India in Jaffna, Mr. S. Balachandran, members of Tri- Forces of Sri Lanka, several officials from Government of Sri Lanka and Government of India participated in the inaugural event. 3. High Commissioner, in his address, noted that the bilateral relations between India and Sri Lanka have now truly touched the sky! He added that the inaugural flight was yet another example of India’s commitment to continue with people- oriented development projects in Sri Lanka. It was also a reflection of the shared commitment to further strengthen people-to-people ties between India and Sri Lanka, which lies at the heart of the bilateral relationship. High Commissioner recalled the words of Prime Minister Hon. -

Loan Halt Creates Further Delay

DISPLACED BY LONG-TERM Govt. sets agenda: DEVELOPMENT THE LONG 20A gets priority WAIT CONTINUES RS. 70.00 PAGES 64 / SECTIONS 6 VOL. 02 – NO. 47 SUNDAY, AUGUST 16, 2020 TNA RECEDES IMF SUPPORT ONLY POLITICAL IF UNCONDITIONAL LEADERSHIP – GOVERNOR »SEE PAGE 6 »SEE PAGE 7 »SEE BUSINESS PAGE 1 »SEE PAGES 8 & 9 For verified information on the GENERAL PREVENTIVE GUIDELINES COVID-19 LOCAL CASES COVID-19 CASES coronavirus (Covid-19) contact any of the IN THE WORLD following authorities ACTIVE CASES TOTAL CASES 1999 TOTAL CASES Health Promotion Bureau 2,886 Suwasariya Quarantine Unit 0112 112 705 21,154,001 Ambulance Service Epidemiology Unit 0112 695 112 DEATHS RECOVERED Govt. coronavirus hotline 0113071073 Wash hands with soap Wear a commercially Maintain a minimum Use gloves when shopping, Use traditional Sri Lankan Always wear a mask, avoid DEATHS RECOVERD 1990 for 40-60 seconds, or rub available mask/cloth mask distance of 1 metre using public transport, etc. greeting at all times crowded vehicles, maintain 2,658 PRESIDENTIAL SPECIAL TASK FORCE FOR ESSENTIAL SERVICES hands with alcohol-based or a surgical mask if showing from others, especially in and discard into a lidded instead of handshaking, distance, and wash hands 11 758,942 13,980,941 Telephone 0114354854, 0114733600 Fax 0112333066, 0114354882 handrub for 20-30 seconds respiratory symptoms public places bin lined with a bag hugging, and/or kissing before and after travelling 217 Hotline 0113456200-4 Email [email protected] THE ABOVE STATISTICS ARE CONFIRMED UP UNTIL 6.00 P.M. ON 14 AUGUST 2020 No UNP in the House BY OUR POLITICAL EDITOR z National List slot vacant z Working Committee undecided The United National Party (UNP) has decided to seek The decision to seek more time to Sunday Morning that the party would possible to not name the National List ended on Friday (14). -

Minutes of Parliament for 21.05.2019

(Eighth Parliament - Third Session ) No . 61 . ] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Tuesday, May 21, 2019 at 1.00 p. m. PRESENT ::: Hon. Karu Jayasuriya, Speaker Hon. J. M. Ananda Kumarasiri, Deputy Speaker and the Chair of Committees Hon. Selvam Adaikkalanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Ranil Wickremesinghe, Prime Minister and Minister of National Policies, Economic Affairs, Resettlement & Rehabilitation, Northern Province Development and Youth Affairs Hon. (Mrs.) Thalatha Atukorale, Minister of Justice & Prison Reforms Hon. Wajira Abeywardana, Minister of Internal & Home Affairs and Provincial Councils & Local Government Hon. John Amaratunga, Minister of Tourism Development, Wildlife and Christian Religious Affairs Hon. Gayantha Karunatileka, Minister of Lands and Parliamentary Reforms and Chief Government Whip Hon. Ravi Karunanayake, Minister of Power, Energy and Business Development Hon. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam, Minister of Education Hon. Lakshman Kiriella, Minister of Public Enterprise, Kandyan Heritage and Kandy Development and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. Mano Ganesan, Minister of National Integration, Official Languages, Social Progress and Hindu Religious Affairs Hon. Daya Gamage, Minister of Primary Industries and Social Empowerment Hon. Gamini Jayawickrama Perera, Minister of Buddhasasana & Wayamba Development Hon. Harin Fernando, Minister of Telecommunication, Foreign Employment and Sports Hon. Sajith Premadasa, Minister of Housing, Construction and Cultural Affairs Hon. (Mrs.) Chandrani Bandara, Minister of Women & Child Affairs and Dry Zone Development Hon. R. M. Ranjith Madduma Bandara, Minister of Public Administration & Disaster Management ( 2 ) M. No. 61 Hon. Rishad Bathiudeen, Minister of Industry & Commerce, Resettlement of Protracted Displaced Persons, Co -operative Development and Vocational Training & Skills Development Hon. Tilak Marapana, Minister of Foreign Affairs Hon. Sagala Ratnayaka, Minister of Ports & Shipping and Southern Development Hon.